It is well known that the Etruscans were the first population of Italy to adopt a writing system based on an alphabet, which was derived from some variants of theGreek alphabet and which, according to an account more “mythological” than real, reported by Tacitus, was introduced into the lands of the Etruscans by Demaratus of Corinth, a wealthy citizen of the important Greek polis and the father of the king of Rome Tarquinius Priscus. The story is unfounded, and we can therefore trace the history of the spread of the alphabet in Etruria thanks to the artifacts that have been preserved: it is therefore possible to assume that the Etruscans became acquainted with the alphabetic script through the medium of settlers from Euboea (an island in Greece from which the first colonizers of what would later become Magna Graecia had departed), who had settled in Campania. With the Euboic settlers, the Etruscans had taken up trade, importing pottery, jewelry, and utensils. Many of the objects the Etruscans bought from the Greek colonists had inscriptions: first, the Etruscans introduced the Greek alphabet as a decorative element for their ceramics, which imitated Greek ones. Then they began not only to interpret and use it, but also to model it according to the sounds of their language. The rationale for the introduction of writing in Etruria was, however, very complex: “it is possible that the causes,” wrote the distinguished Etruscologist Massimo Pallottino, “were several: practical needs of a commercial nature not divorced, however, we believe, from an unrelenting pressure of supply and demand for culture in the tendency of the nascent local aristocracies and presumably of cult circles to embrace Eastern and Greek models and customs; more or less concomitant, but perhaps distinct, penetrations from the ports of Caere, Tarquinia, and Vulci.” In essence, “not a single, instantaneous event, but rather an articulated process, perhaps taking place or at least being completed through more than one generation.”

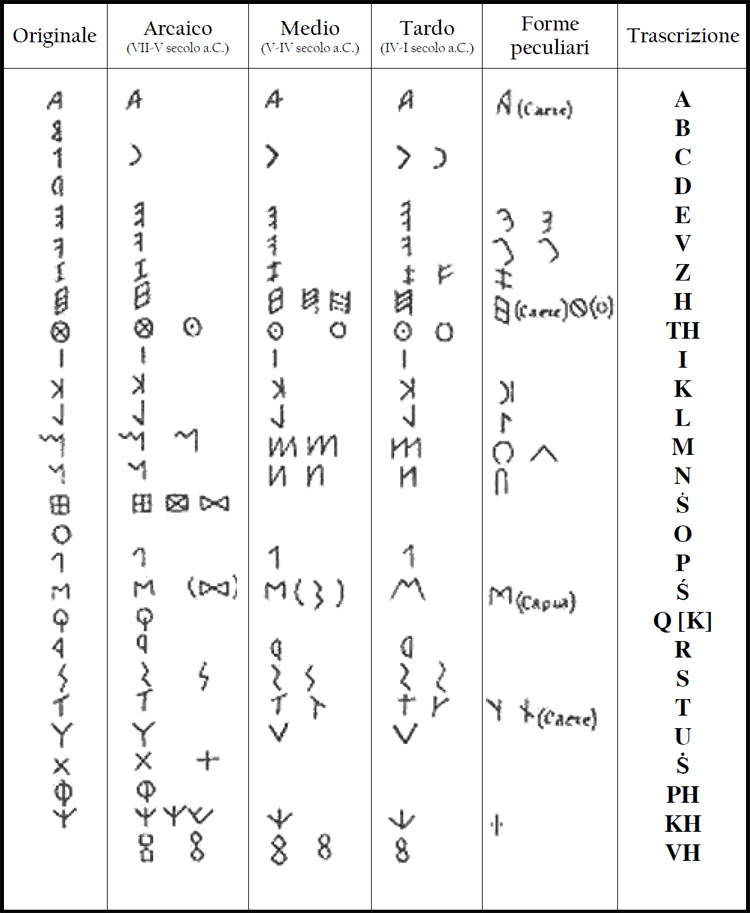

The Etruscan alphabet, over the centuries, underwent evolutions: for example, the letters “B” and “D” derived from Greek were eliminated, as they had no corresponding sounds in the spoken language, and the same happened with the “O” (it is likely that the Etruscans pronounced it as we pronounce “U”), and some signs underwent slight modifications. For example, the gamma that the Greeks used for the hard (or “sonorous,” according to the technical terms of phonology) “g” sound was transformed by the Etruscans, who brought it to take on a crescent shape (the modern “C”), and since the inhabitants of Tuscany at the time did not pronounce the “g” sound, they used it to express the hard “c” sound, with the same function as the letter “K” (which, on the other hand, from the Greek alphabet did not undergo any transformation). “C” and “K” were used to pronounce the same sound (exactly as happens in modern Italian with “C” and “Q,” the difference between which is only graphic and not phonetic), and preferences in the use of one or the other sign varied on a regional basis (for example, in the north the use of “K” is more attested, while in the south in more recent times the use of “C” became established, and in archaic times the letter changed according to the vowel that followed it, and syllables were thus composed: ka, ce, ci, qu). The letter C then passed from the Etruscan alphabet to the Latin alphabet, which, contrary to what was thought in the past, is not of Etruscan derivation, but also descended from the Greek alphabet, although it accommodated some phenomena peculiar to Etruscan writing.

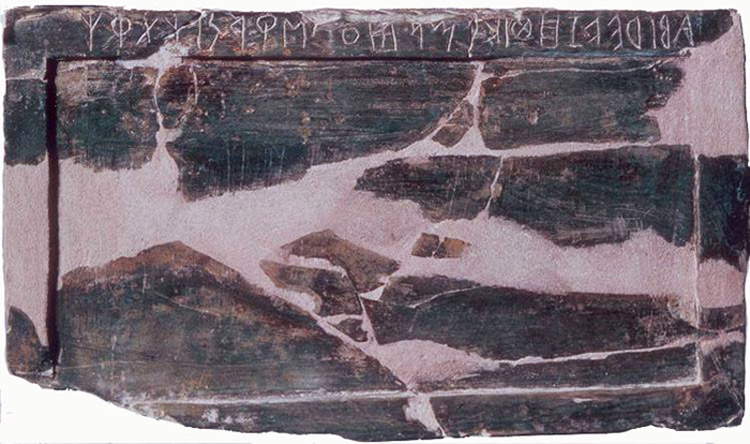

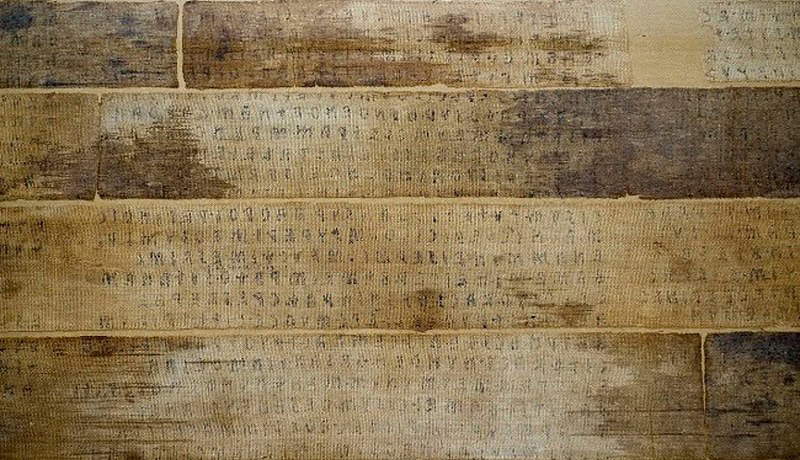

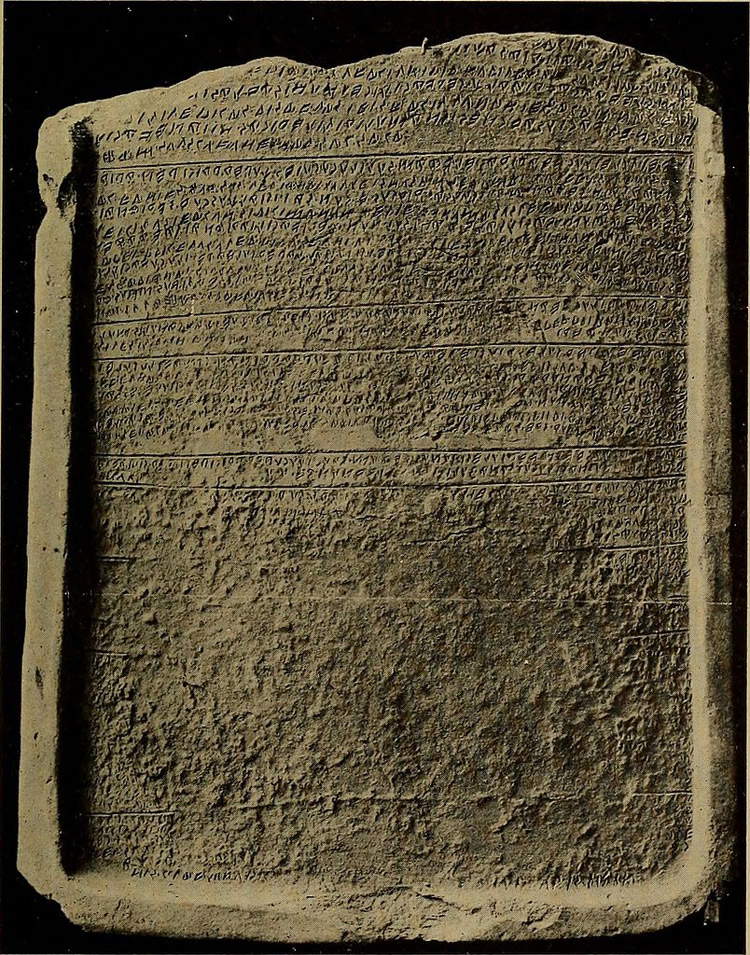

One of the earliest preserved Etruscan alphabets is the one we can read on a tablet found at Marsiliana d’Albegna, in southern Maremma, and now preserved at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. Found in the tomb of an aristocrat, the tablet represents the oldest example of a complete Etruscan alphabet that we know of: in fact, the work can be dated to around 670 B.C., and it provides us with several pieces of information. The first, the most obvious, is the fact that the early Etruscan alphabet is very similar, almost identical, to the Greek alphabet. The second is thepattern of writing: the Etruscans wrote from right to left, or sometimes (although the evidence is not frequent) according to a bustrofedic system (found mainly in the oldest finds), that is, from right to left and then from left to right in alternating lines. Rare, however, are the attestations of writing from left to right. Again, the object in the Archaeological Museum in Florence gives us an insight into one of the techniques the Etruscans used for writing: engraving on an ivory or bronze tablet (in this case an ivory tablet). But the Etruscans wrote on any medium: vases, stones, memorial stones, walls, tombs, urns, wall paintings. And we also know that they used ink, because a text written in ink on linen bands has come down to us: dating from the third century B.C. and known as Liber Linteus Zagabriensis (“Linen Book of Zagreb”), it is the only find of its kind that we know of, and it also coincides with the longest text in the Etruscan language currently known (it is a cloth that wrapped a mummy and the text is nothing more than a liturgical calendar with festivals and rituals: it was rediscovered in Egypt in the mid-19th century and purchased by Croatian collector Mihajlo Bari�?, who later donated it to the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb, where it is still preserved). Finally, the Marsiliana d’Albegna tablet had a practical character: that is, it served to guide the scribe in writing texts.

|

| The Etruscan alphabet |

|

| Tablet of Marsiliana d’Albegna (c. 670 BC; ivory, 8.8 x 5 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale) |

|

| Liber linteus Zagrabiensis (3rd century BC; linen cloth, originally 340 x 45 cm; Zagreb, Archaeological Museum) |

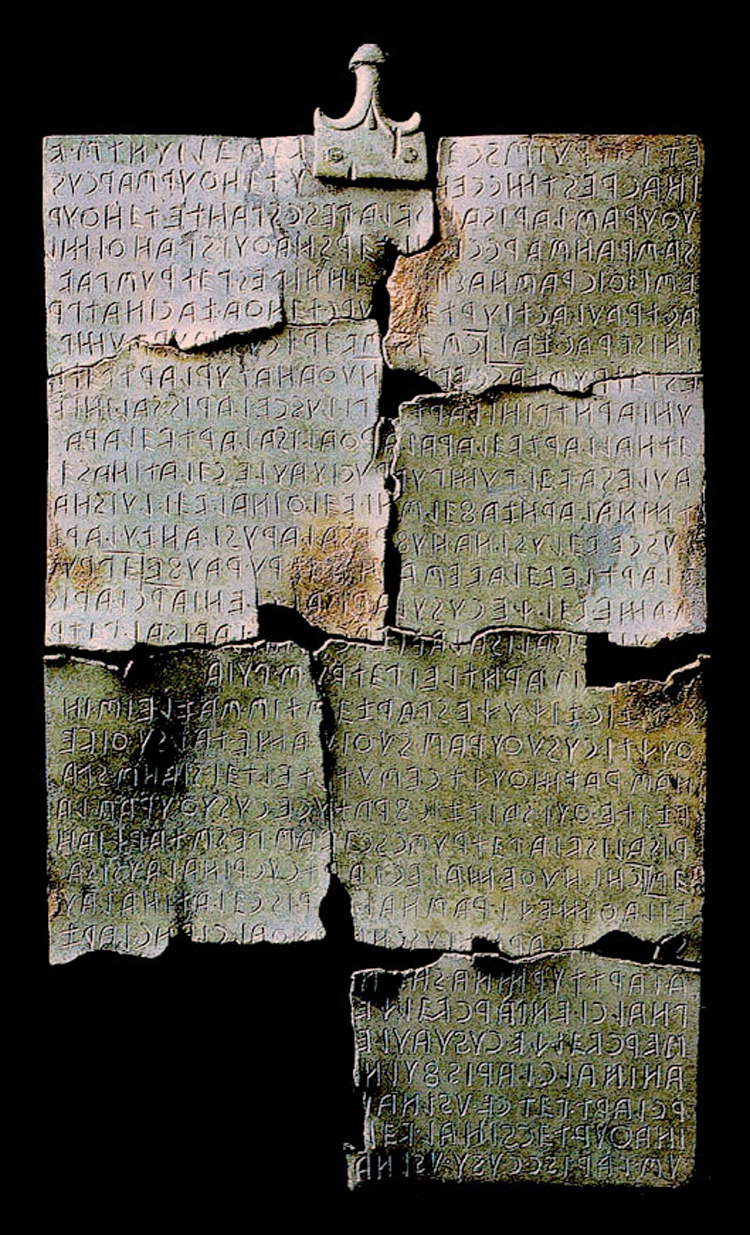

But what were the practical uses to which the Etruscans destined writing? It should be specified that almost all the Etruscan texts that have come down to us (about twelve thousand) are related to religious ceremonial or funerary rituals: in fact, the vast majority of Etruscan written evidence consists of inscriptions on tombs, dedications to deities, and epigraphs. There are, however, interesting cases, though rare, that have the merit of introducing us into the daily life of the Etruscans. In this sense, the certainly most interesting document is the so-called Tabula Cortonensis (“Table of Cortona”), a bronze table that also ranks third in the “ranking” of the longest Etruscan texts that we know of (first is the aforementioned Liber Linteus Zagabriensis, about one thousand two hundred words, while the second longest, about three hundred and ninety words, is the Tabula Capuana, which contains another liturgical calendar). On the other hand, the Tabula Cortonensis, found in Camucia, a hamlet of Cortona, and preserved at present in the Museum of the Etruscan Academy in Cortona, consists of about two hundred words arranged on thirty-two lines on the front face and eight on the back face, and is interesting also because it gives us a very good understanding of another peculiarity of the Etruscans’ way of writing, that they did not use, as happens in our writing, spaces to separate words: they were in fact used to write all the words in succession and separate them by means of a dot that was placed approximately halfway up the height of the letters.

The Tabula Cortonensis has been interpreted as a notarial deed regulating the buying and selling of property. This deed, dating from the second century B.C., was issued by the “zilath mechí rasnai,” the chief magistrate of the Etruscan city (roughly corresponding to the praetor of the Romans: a figure who had, among others, the power to settle civil matters between citizens): according to what we read in the tablet, which has come down to us in seven of the eight fragments into which it was anciently broken, the buyer was a family consortium of three people belonging to the Cusu family and named Velche, Laris, and Lariza, while the seller was an oil merchant, of humble origins but very wealthy, named Petru Scevas. We know that the buying and selling was regulated through a particular rite, also common among the Romans, the so-called in iure cessio: it was a mode of purchase that enacted a mock trial where the buyer claimed rights to the seller’s property. The latter, when questioned by the magistrate, would not answer the questions causing the trial to be resolved by the assignment of the object of the sham litigation to the buyer.

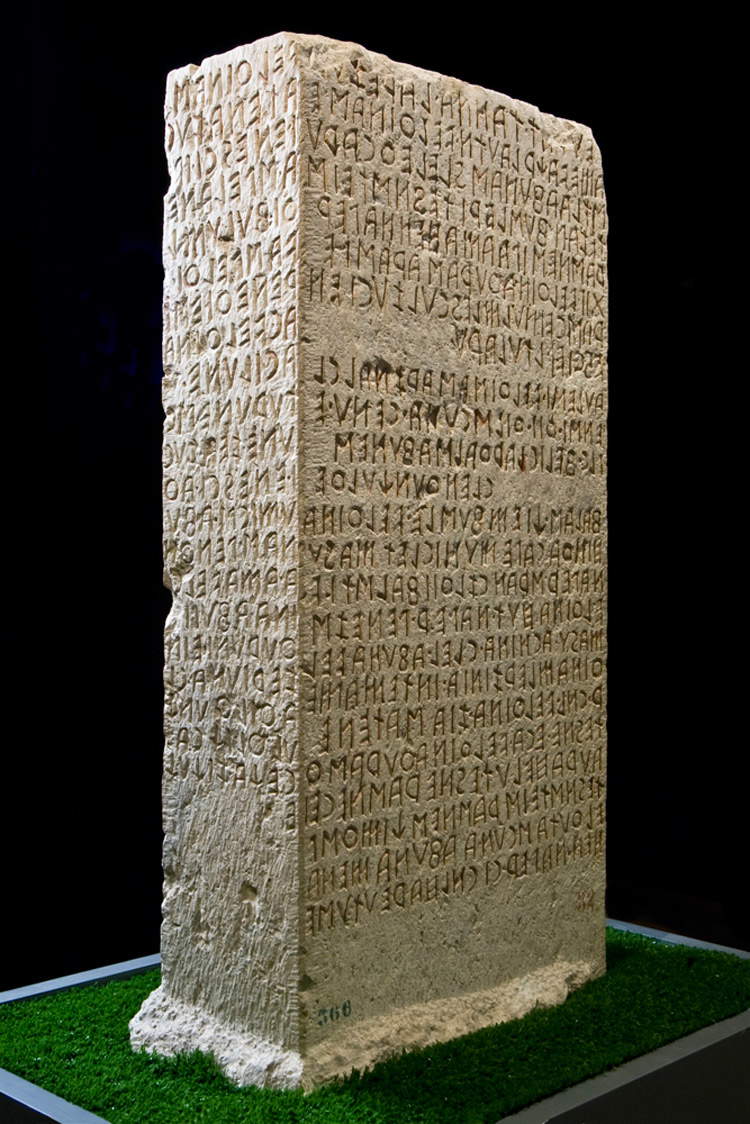

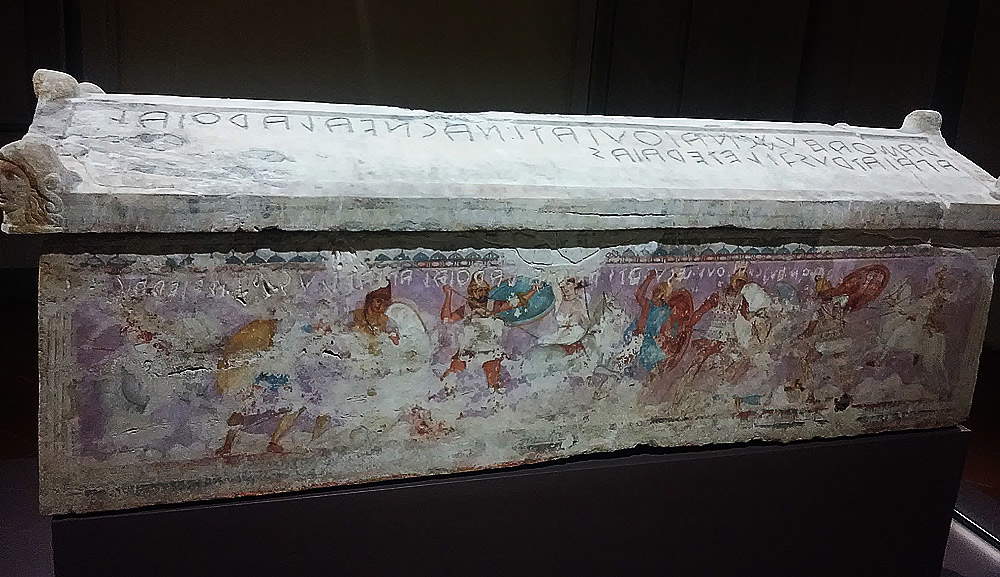

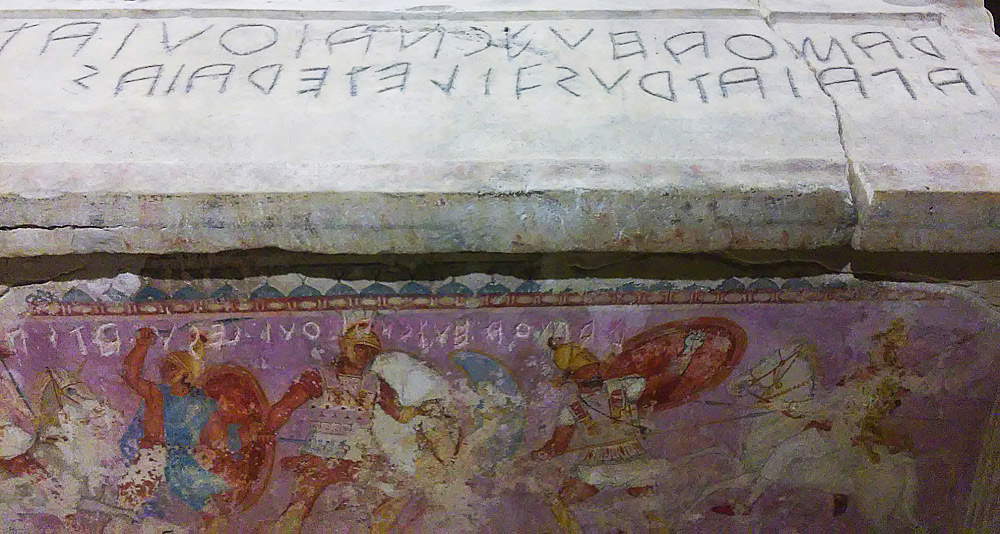

Another decidedly interesting document is the Cippo di Perugia, found in 1822 near the Umbrian capital and currently housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Umbria. It is a large travertine cippus that we have to imagine placed within a property shared by two families, that of the Velthina, originally from Etruscan Perugia, and those of the Afuna, who instead came from Chiusi. The cippus, dating to a period between the third and second centuries B.C., contains an inscription regulating the terms of use of the property, in which there was a tomb of the Velthina family. The deed mentions a judge, named Larth Rezu, in whose presence the two families allegedly agreed on the covenant for use of the property. The final zichuche (“it is written”) formula seals the validity of the agreement. Less interesting in content, but decidedly more spectacular, is the inscription we find on the Sarcophagus of the Amazons, an extraordinary and extremely rare sarcophagus painted in tempera on stone with scenes from the myth of Actaeon and featuring a battle of Amazons: the work was found in Tarquinia and was manufactured in Greece although, in all likelihood, it was decorated in Italy, with a painting that represents at the moment the only example of this type in the sphere of Etruscan art, and which strikes us by its modernity, its freshness, the individual characterization of the figures, and the degree of naturalism. As for the inscription, we find on the lid a long inscription that makes known the name of the deceased and the name of the member of her family who had the sarcophagus made. The inscription reads Ramtha Huzcnai thui ati nacnva Larthial Apaiatrus zileteraias, or “Here lies Ramtha Huzcnai, grandmother of Larth Apaiatru, zilath of the foreigners.” Then there is another unique piece, the so-called liver of Piacenza, which has enabled us to learn the names of many deities: it is a bronze liver, preserved in the Civic Museums of Palazzo Farnese in Piacenza, divided into boxes with the names of the gods, which was used to offer a model of divination (the Etruscans practiced this very rite through the entrails of animals, in which they claimed to read the will of the gods). Thus, we know that the Etruscans worshipped, among others, the sun god (Cautha), the goddess of fortune (Cilens), the god of wine (Fuflus), the god of the woods (Selvans), and the god of the seas (Nethuns), but the most important gods were Tin (corresponding to the Jupiter of the Romans) and Uni (his wife, corresponding to the Latin Juno).

It is fair to imagine that, through all these documents, we have managed to obtain a good level of knowledge of the Etruscan language. Unfortunately, however, our cognition in this respect remains very deficient, and Etruscan is for us still, essentially, a mysterious language: there are in fact too few texts, and almost always too specific (and moreover, most of them contain almost exclusively names of persons) to have allowed us to arrive at a full understanding of the Etruscan language, so much so that in many texts there appear words that are still untranslatable (an example is precisely the Liber Linteus Zagabriensis, which still has some passages with a meaning that is still obscure). We do, however, know several words from Etruscan. Some are those related to the family: apa (father), ati (mother), apa nacnva and ati nacnva (grandfather and grandmother, literally “big father” and “big mother”), ruva (brother), clan (son), sech (daughter), puia (wife), nefts (granddaughter), papals (grandson, referring to grandfather), tetals (grandson, referring to grandmother), husiur (children), tusurthiri (bride). Others are animal names: leu (lion), hiuls (owl), thevru (bull). We then know several terms related to state and society: methlum (state), spur (city), spurana (civic), lauchume (consul), camthi (censor), tular (border). Given the abundance of objects related to funerary ritual, we have much knowledge about specific terminology: hinthial (soul), mutna (sarcophagus), murs (urn), penthna (cippus), suthi (tomb), suthina (funerary). We also know the numerals from one to ten, although not all scholars agree on some of the numbers (for example, on four and six, which could be reversed): thu (1), zal (2), ci (3), ša (4), mach (5), huth (6), semph (7), cezp (8), nurph (9), šar (10). The Etruscans counted on a decimal basis, and the tens (except for the number twenty, zathrum) were formed with the suffix -alch: cialch (30), sealch (40), machalch (50), huthalch (60), and so on. The findings have also enabled us to come to a good understanding of Etruscan grammar: thus we know that the Etruscans had declensions with cases as in Latin, that verbs had tenses to indicate present, past and future, that they also used the subjunctive. And of course there is no shortage of the term by which the Etruscans called themselves: rasna.

|

| Tabula Cortonensis (3rd-2nd century B.C.; bronze, 28.5 x 45.8 cm; Cortona, Museum of the Etruscan Academy) |

|

| Tabula Capuana (first half of 5th century BC; terracotta, 62 x 48 cm; Berlin, Altes Museum) |

|

| Cippo di Perugia (3rd-2nd century BC; travertine, 149 x 54 x 24 cm; Perugia, Museo Archeologico Nazionale dell’Umbria) |

|

| Sarcophagus of the Amazons (late 4th century BC; stone decorated with tempera, case 194 x 62 x 50 cm; Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale) |

|

| Detail of the Sarcophagus of the Amazons |

|

| Liver of Piacenza (late 2nd-early 1st century BC; 7.6 x 6 x 2.6 cm; Piacenza, Civic Museums of Palazzo Farnese) |

Finally, we know of the existence of Etruscan literature, of which, however, no evidence has survived: in fact, we know the works of Greek and Latin classicism because they have been handed down to us through copies compiled during the Middle Ages. However, since the Etruscan language was not known in the Middle Ages, the copyists of the time did not preserve memory of the productions of Etruria. Through quotations from Latin authors, however, we know that the Etruscans wrote religious books, theatrical works (Varro mentions an Etruscan playwright named Volnio), historiographical collections, scientific books, and, in all likelihood, poetic works as well. And Etruscan literary production must have been decidedly important if an author such as Livy states that, at a time corresponding to the end of the fourth century B.C., young men from Rome went to Caere, one of the most powerful Etruscan cities, today’s Cerveteri, to study literature. Specifically, with reference to a politician of the time, Livy wrote in his treatise Ab urbe condita that “he had been sent to Caere and had studied the Etruscan language and literature. I know of authors who say that at that time young Romans studied Etruscan literature just as we study Greek literature today.”

Etruscan writing was of considerable importance in Italy because the alphabet of the Etruscans spread to several regions, especially northern Italy and the Alpine regions, and may have lent elements to the Runic alphabet as well. It is therefore undeniable that the Etruscans were the first to introduce one of the most important innovations in the history of civilization in Italy.

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.