The shadow of an intimate and deep mystery envelops Wainer Vaccari’s most recent works. Not that the Modenese artist in the past had accustomed the public to works more agile to probe: Since the beginning of his career, on which has always weighed the fascination with symbolism à la Böcklin, an artist beloved by Vaccari, his canvases have always appeared as if concealed by an inscrutable blanket, which filters reality, restoring it under the guise of a distant and wonderful world, where an extravagant population, no less surprising than the places that serve as theaters for his actions, is quietly bustling about, difficult to decipher. In these new works, presented between the end of 2021 and the beginning of 2022 at the solo exhibition Certezze soggettive held at the Galleria Civica in Trento, memories of his native lands surface, also evoked by the titles. In the Lands of Gonzaga, for example: a canvas where some strong-armed men are stirring the waters of a lake, protected by the somber foliage that barely conceals the unusual and disturbing presence of a slimy animal that pops up behind one of them. It is the same landscape that returns in works such as Sotto riva, where the artist focuses on a character emerging from the woods to lap the water with her lips, or as Dove l’acqua è dolce: here, a nymph leans out over the lake leaving the woods, as if she wants to dive into the water. Trees, perhaps cypresses, stand out in the background, reminiscent of those of the beloved Böcklin. The air becomes heavy with a misty mist that tinges the sky and water with silvery tones: it is the light of the Po Valley winters, the suspended light of the Po Valley.

It survives, in Vaccari’s works, that matter so dense and oily c’is typical of certain Emilian painting, of that expressive and natural-oriented line that has traversed it over the centuries, starting at least from the 14th century. Francesco Arcangeli, who was perhaps the greatest scholar of that line, had to speak of body, action, feeling and fantasy, between naturalism and expressionism. The same elements have never abandoned Vaccari’s poetics, which in his latest works has been imbued with further lyrical intonations: the Emilian landscape is thus transfigured by this caliginous veil that restores a dreamlike image, as in the Symbolist visions of Fernand Khnopff and Alphonse Osbert, which takes shape under this brushstroke connoted by a more marked immediacy, but which bears the signs of the turning point that Wainer Vaccari imprinted on his work in the early 2000s, when he regenerated his subjects by subjecting them to a kind of scanning highlighted by what he himself called “expanded pixels.” Here they are, then, Wainer Vaccari’s new works, which do not cease to “aspire to an inalienable and fulfilling desire,” as Flavio Arensi wrote.

They are visions of water, one would think: the liquid element, always present in Vaccari’s research, is central, archetypal in the Jungian sense of the term, referring to primordial images that resurface from the unconscious. One looks at In the Lands of the Gonzaga, and the mists of Emilia come to mind, the memory of the drearyness of the harsh season of which the Po Plain knows how to be capable rises, one seems to hear the voice of Umberto Bellintani’s poems, the genius loci of lower Mantua who sang green jade skies on an evening along the banks of the Po, who listened to the arcane voices echoing on the waters of the ditches, who evoked the melancholy of the countryside at sunset, capable of inspiring him with deep existential questions. One looks at In the Valley of the Helvetians, and one cannot help but think of the Switzerland where Vaccari spent his childhood and where he measured himself as a child with that “widespread, ancestral spirituality” that the artist saw the inhabitants practicing in an unusual combination of Protestantism and paganism, “a kind of permanence of ancient pagan rituals, linked to the peasant culture and the cycle of the seasons,” as Vaccari himself explained in an interview with Gabriele Lorenzoni in the catalog of Certezze soggettivezze. It is a return in every sense of the word, which began in the mid-1910s of the new millennium, that urged Vaccari toward these new works: a return to the language of the 1980s and 1990s past the most extreme phase of his activity, a return to subjects once cherished. A “new necessity,” he himself called it: “in fact, the propulsive thrust of the previous path had run out and I could only return to my steps, certainly with renewed eyes and spirit.”

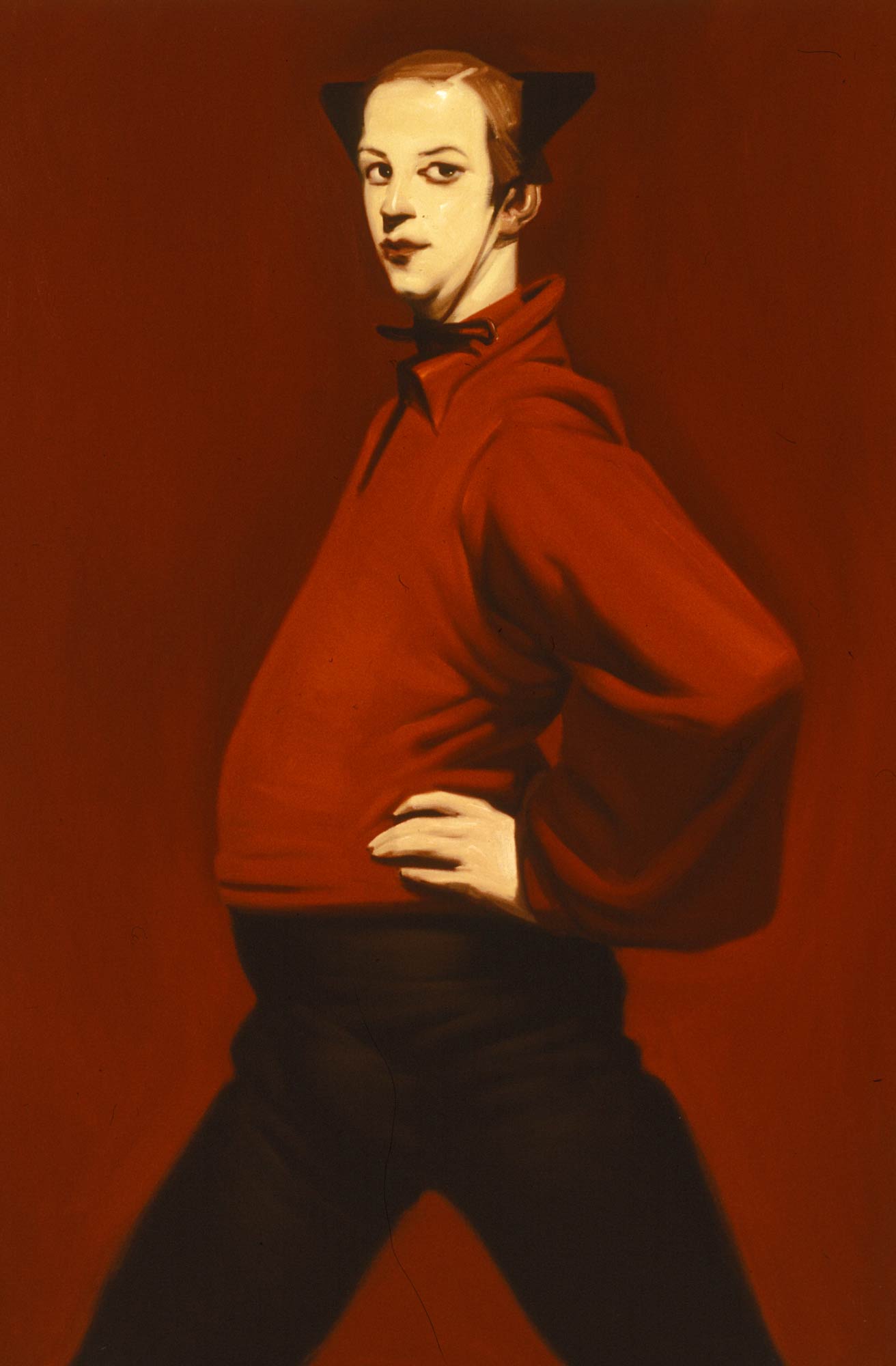

It is necessary to go back to 1983 in order to understand, on the one hand, the origins of this itinerary and, on the other, the events that pressed upon it. That year, Vaccari’s first solo exhibition was held at Mazzoli’s in Modena, which was made possible by his audacity: Emilio Mazzoli had known his work, asked him to sell him all his recent production, and Vaccari, openly jealous of his work, demanded an exhibition in exchange for the works. The exhibition was titled Immagini pompose, profonde, seriose and was curated by Achille Bonito Oliva. “To the anaemia of a colorless reality,” Bonito Oliva wrote in the critical text accompanying the exhibition, “the artist responds with the representation of another disease, that of exuberance, through which to compensate for the quantitative proportion that overpowers him. The incandescent temperature of the work shows him how art is a procedure that, while adopting its own internal rules and specific languages, creates gaps in the opacity of the everyday, introduces a different visibility of the world.” And they were true exuberance, true yearning to tear through the grayness of custom, true visionary sensibility the credentials with which Vaccari presented himself to the world. Literally: the 1982 self-portrait, which has become one of his most famous images, first of all testifies to a desire to work on his own identity, to investigate the artist’s idea of himself, and is then an obvious poetic manifesto. The artist presents himself in a three-quarter pose, while in his right hand he holds a palette and a pair of brushes, a firm and uncompromising image of a seventeenth-century self-portrait, were it not for the fact that, in addition to the brushes, the painter also holds a cane, and decides to address the relative with a sardonic grin, and encased in a huge black palandrana that still recalls, self-mocking, Böcklin’s attire in the well-known self-portrait in the Nationalgalerie in Berlin. And then, the god Pan, the woodland deity that Christianity has transmuted into a negative symbol, bites his chest and becomes a feral allegory of his inspiration. Thus, a mocking vein that does not spare even his self-image is manifest from the very beginning. And which returns frequently in his paintings: it happens, for example, in the Merchants, where a series of characters wearing ridiculous headgear (and among whom we see, in a mirror, Vaccari himself) is engaged in actions whose meaning we do not understand, and which sometimes appear to us as pervaded by a soul of madness. This impossibility of interpreting the logic of what the figures do in Vaccari’s paintings is another constant in his painting: indefiniteness is the approach with which Vaccari reads an uncertain reality that is equally impossible to understand according to predetermined patterns.

Here, then, irony takes over again, in this painting that grafts the solemn spatial scansion of Piero della Francesca in the Bacci Chapel (recalled, as Vittorio Sgarbi has rightly noted, even in the bizarre shapes of the hats, which Vaccari exaggerates to the point of paroxysm) onto a figurative culture built on the works of the Neue Sachlichkeit, of which Vaccari is one of the most intelligent interpreters. “Despite the abysmal differences,” Vaccari said of the German painters of the early 20th century, motivating his recourse to that repertoire of images, “they were artists who looked at the reality of the human body, the landscape, everyday life: their visionary and expressionist force attracted me, led me to deform the figures, to tear apart human features while always remaining within the figure.” There is first and foremost Christian Schad, perhaps the least radical of the new objectivists, from whom Vaccari borrows the ability to return full, precise and razor-trimmed figures to the canvas, but distant, disturbing to the point of provoking unease and stirrings of disturbance if not anguish, without one really understanding why. With a play on suggestion one can also arrive at the lonely and disillusioned realism of Wilhelm Lachnit. One can then add to it the disturbing and sharp concreteness of the magic realism of Cagnaccio da San Pietro. But one can go even further back: The Merchants also harkens back to the militias that abound in seventeenth-century Dutch painting, for example. A work like In the Shadow of Cathedrals cites the Kimbell Art Museum’s Temptations of St. Anthony, most famously attributed to Michelangelo. The Daytime Roundabout, right from its title, harkens back to Rembrandt, but that procession of shaven-skulled Orientals, who have populated Vaccari’s canvases for more than 30 years, harks back to Bruegel’s Parable of the Blind. And again The Fishermen’s Woman, lying in nature like Piero di Cosimo’s lifeless Procri, but with a body that harks back to the sensual seventeenth-century Magdalene.

Vaccari’s technique, moreover, takes us on a journey back in time. “He works on style,” wrote Flaminio Gualdoni. A style “that becomes loose and very precise, made up of short taps and patient glazes, to unravel a chromatic skein in which Vadyckian browns, on the threshold of gray, and dombra earths, and French blacks, entangle short and strong intromissions of garanza lacquer, of cinnabar, dindigo, in the garments of the figures. And dripping over everything is an astonished golden light or, elsewhere, silvery, but firm, sharp, barely irritated by strong highlights, silhouetting figures and spaces as in enigmatic sixteenth-century interiors, or in dreamy Boecklinesque natural settings.” Add to that an innate sense for the monumental, as is evident when observing the Girovago, a kind of ironic homage to Antonio Donghi’s Juggler, and perhaps even more so from his figures of divers, for which one might venture to discomfort the statuary of an Arturo Martini.

Then there are the situations, the settings, the figures bustling about in activities that seem meaningless to us, the grand theater on which Wainer Vaccari’s mysterious, slow, mad, concentrated, quietly busy comedy is staged. His characters move in a world that is itself indefinite, indecipherable, impossible to place in a precise chronological space. Indefinite, but recognizable: a fantastic world, dark and impenetrable but at the same time almost grotesque, which could be summed up in Sgarbi’s words: “a small paradise made up of uncontaminated nature, of a strange population with massive forms and oriental features, engaged in mysterious rituals, pure as in a fairy tale, sensual at times to the point of provocation, serene on the whole, but not without pungent anxieties.” It is no coincidence that Sgarbi has always related Vaccari’s world to Fellini’s imagery, going so far as to nickname him “the Fellini of the canvas,” in an article published inL’Europeo in 1991.

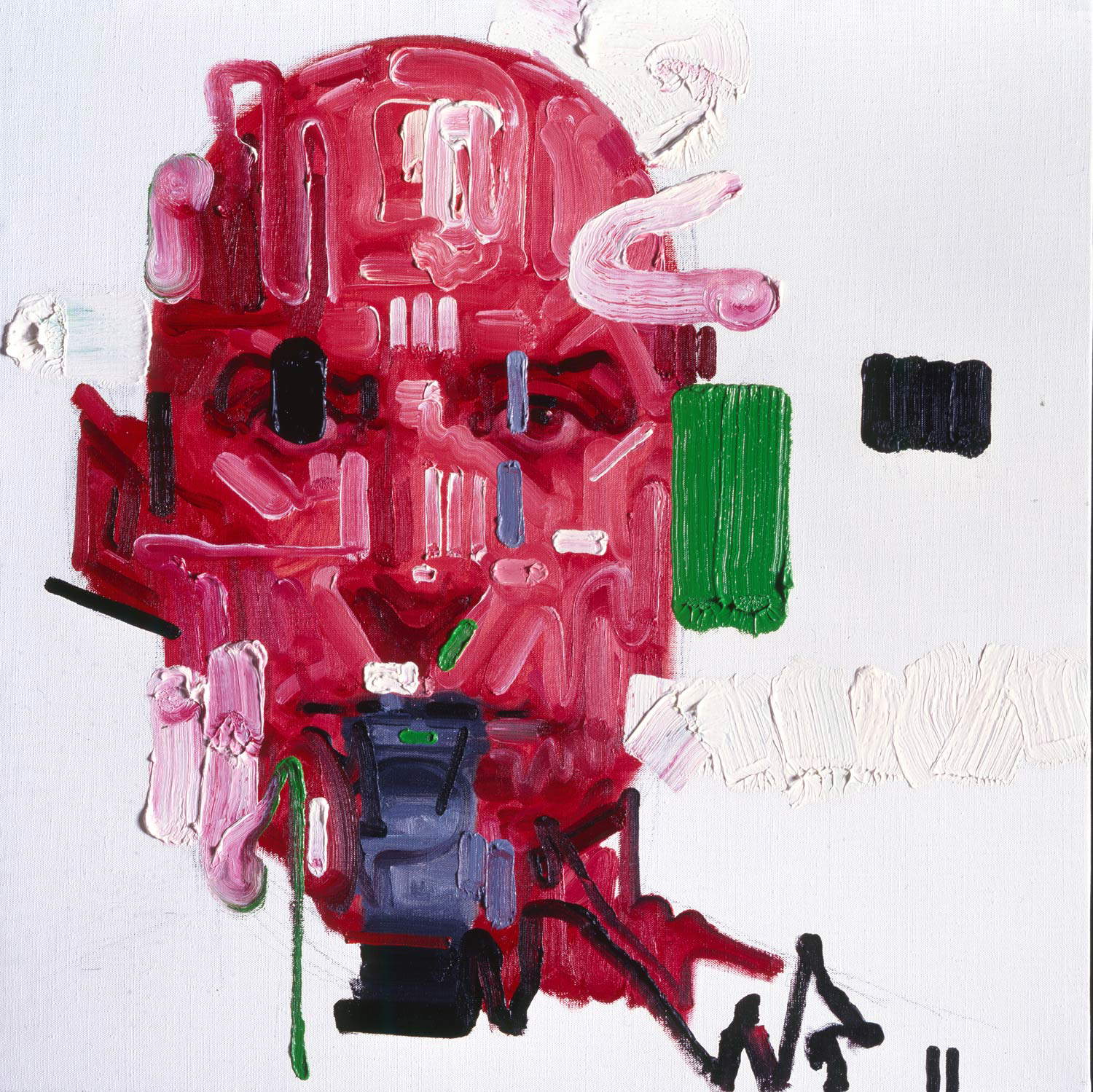

These, then, are the coordinates of the space within which Wainer Vaccari’s art moves. Then, there had been the parenthesis that began in the 1990s and lasted more than ten years, during which the universe of the Emilian painter totally changed, surprising critics with one of the most searing changes of direction that contemporary Italian art has known. A sudden, drastic change of direction, but certainly anything but inconsistent, since for Vaccari painting is first and foremost a necessity. Citations to art history had gradually given way to gravure images, but this was not just a matter of necessity intervened to modify Vaccari’s interests, a circumstance that would not have aroused surprise. The fact is that Vaccari’s own grammar had undergone a radical change: it was as if the painter had begun to speak in another language, completely different from the first. And so from slow, meticulous and meditated his painting had become immediate, fast, almost instinctive and sign-like, it even seemed alien to his poetics. Faces on white backgrounds, composed of marks made with short, rapid brush strokes, and which at a superficial glance seemed to cover images, usually taken from the mass media, but on closer inspection added up to give life to the figure: what appeared to be synthesis was actually analysis. One wondered, then, if any chance of seeing those “paradises” that had distinguished Wainer Vaccari’s art until the late 1990s were extinguished. The answer came after a little more than a decade: a sort of new rappel à l’ordre ensured their reappearance.

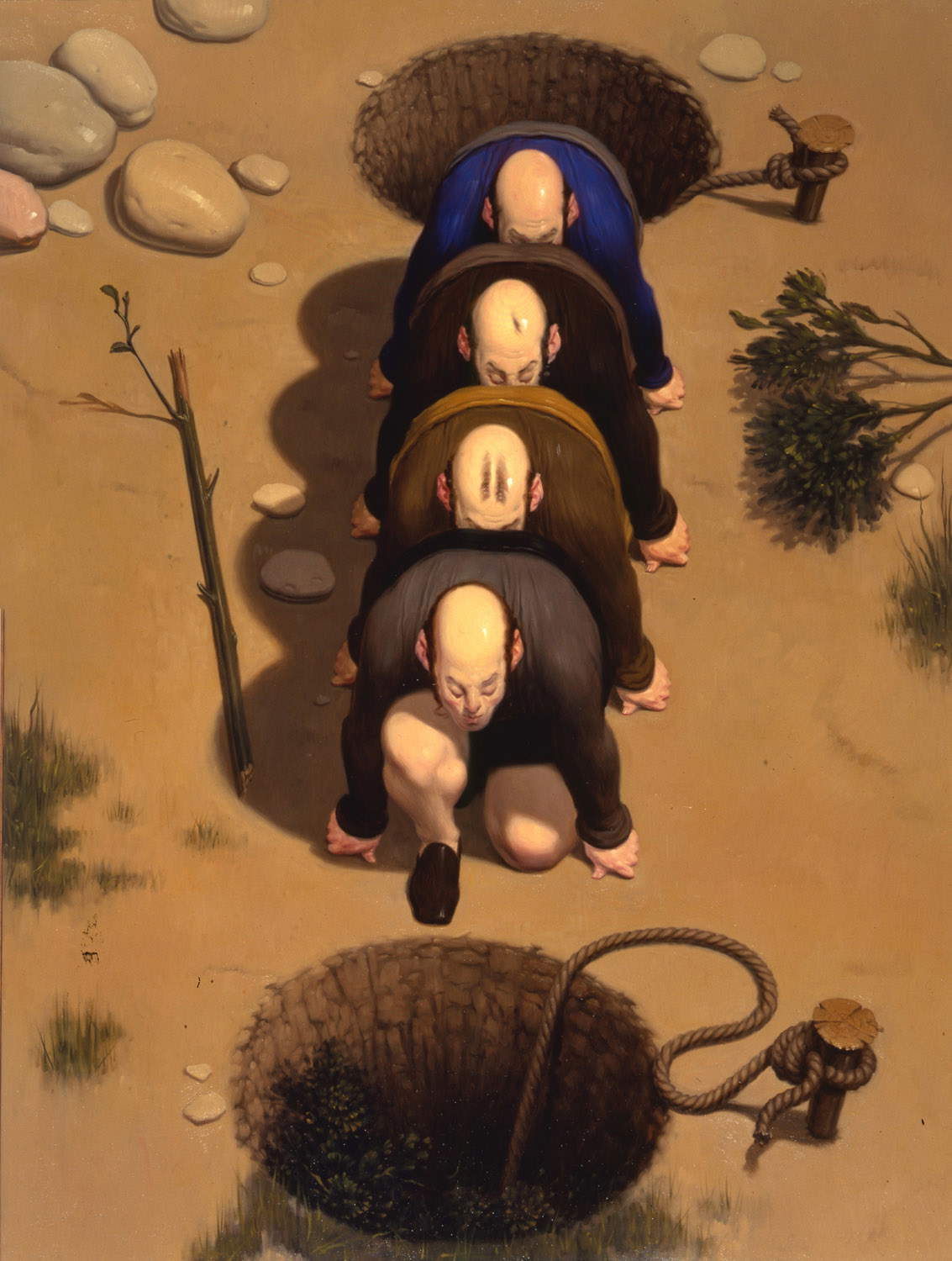

The fantastic worlds are back, the rarefied atmospheres of the early years are back, the poetry of uncertainty is back, even the omnipresent and hermetic Orientals are back (sometimes even in a row as in the Ronde: here they are, for example, climbing the Ghirlandina, the bell tower of Modena Cathedral, in the painting Di torre in torre), the great mystery that intrigues his work and deceives the relative is back. Sometimes they return is the title of the exhibition with which, in this singular palingenesis of which one struggles to find comparable examples in recent times, Vaccari again introduced himself to public and critics, in 2014, at the Levy Gallery in Hamburg. And sometimes Vaccari has returned with deflagrating power, as is the case in Happy Birthday, a work whose title is completely unrelated to what we observe on the surface of the canvas: one of the shaven-headed characters emerges from a pond, and in front of him a woman almost seems to tempt him by spreading her legs wide. What happened before, and what will happen after, is unknown. To the relative the task of trying to penetrate the mystery.

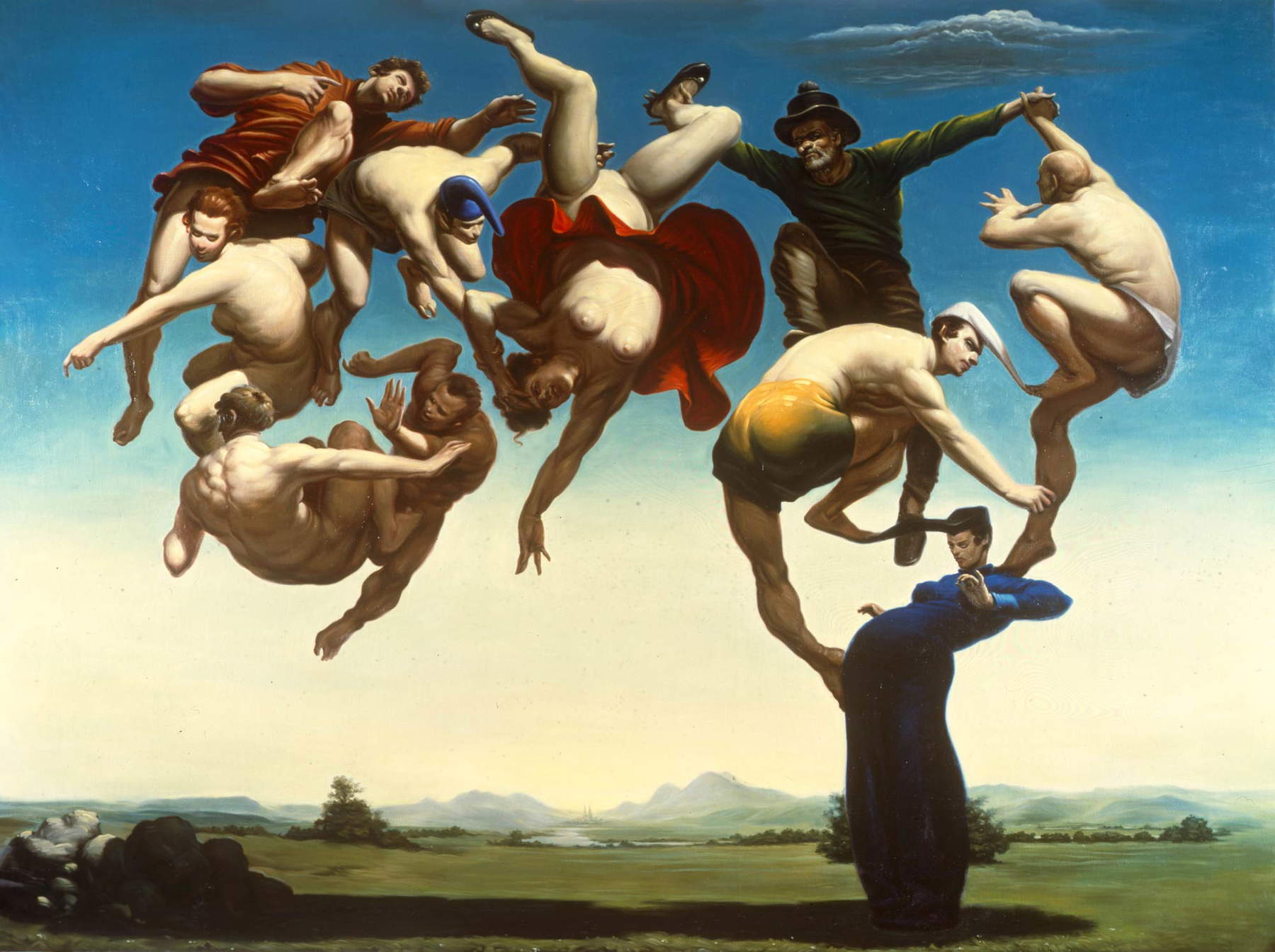

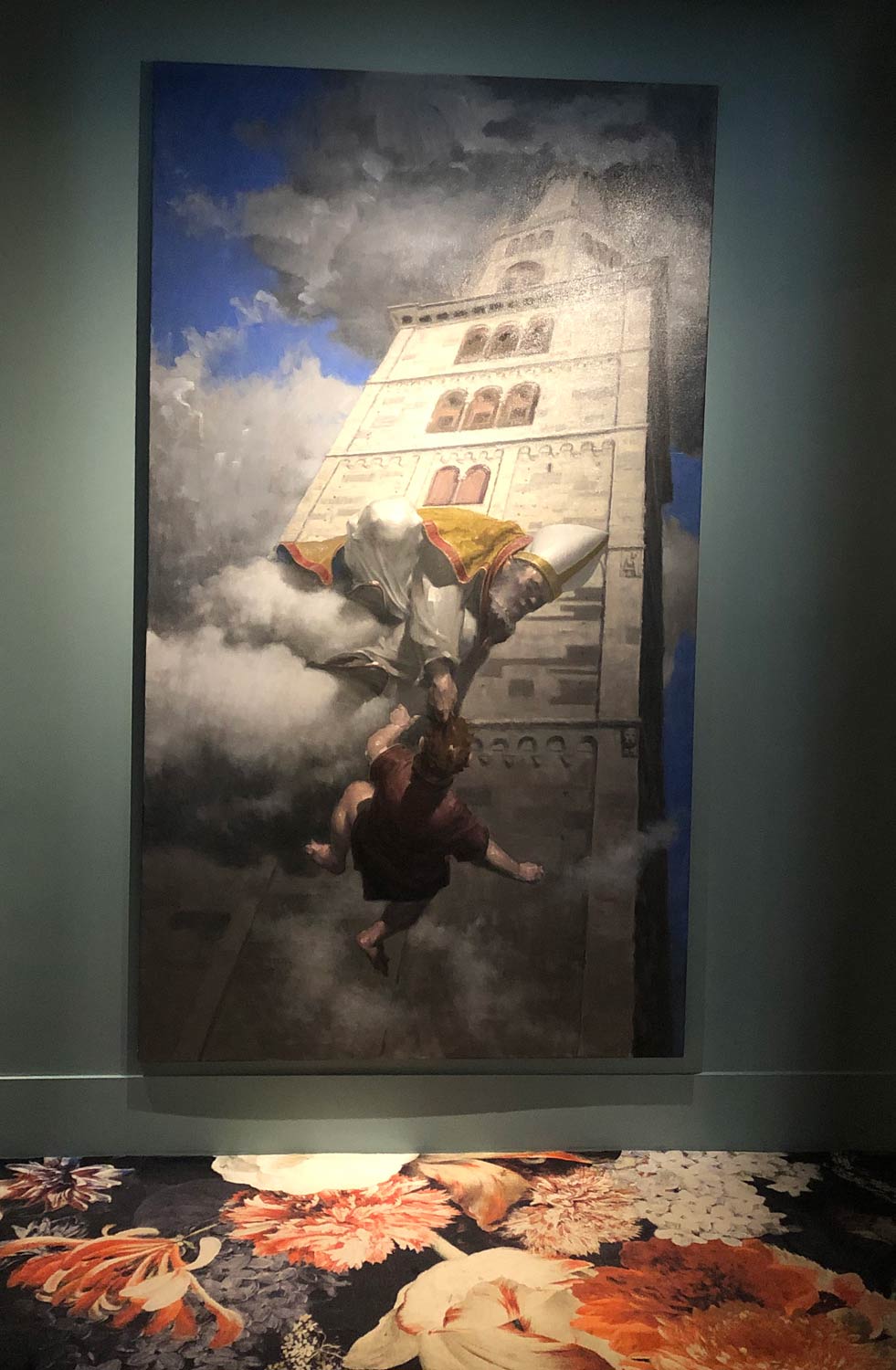

And then, in more recent times, the return to the familiar, to the province, has also become more insistent. A province as a microcosm of roots, of memory, evoked, as we saw at the beginning, with the usual approach that caresses the surreal: if Vaccari finds in Fellini a counterpart in cinema, in literature a parallel could be drawn with the Emilian humor of Cesare Zavattini’s stories. One might think so when looking at one of Wainer Vaccari’s most recent works, the Miracle of San Geminiano, a powerful subtext that welcomes patrons of Massimo Bottura’s Osteria Francescana and recalls Tintoretto’s more daring foreshortenings to recount one of the best-known prodigies of Modena’s patron saint: hagiography has it that a child had climbed with his mother to the Ghirlandina, and that looking out of a window the little boy had plummeted into the void. The mother prayed to the saint, who punctually showed up, and pulled the little one to safety. And Vaccari painted St. Geminianus as he grabs the child (literally, since he grabs him by the hair), a few meters before he hits the ground. “I tried to make the scene more believable,” Vaccari said. “If he was coming from the sky, the only possible vehicle was the cloud. In so many other frescoes, the saints lean against the clouds. Then I said to myself, devid are a bold vision to make the scene dramatic. So I depicted it from below. The child is about to reach the ground. He is only a few meters away. The Ghirlandina is in perspective. The saint grabs him by the hair. My story ends here.” Basically, the tale of an action movie rescue in a painting that refreshes religious iconography.

Attention towards Vaccari has been rising again in recent times, with the rediscovery of figurative painting and, in particular, with the spread of a fashion, among collectors, for painters who throughout the twentieth century, and in some cases even beyond, continued to measure themselves with the languages and themes of surrealism. The choices that underpinned the design of this year’s Venice Biennale are the most eloquent certificate of these renewed interests in a quest that departs from that of the neo-avant-gardes, which also held the field until not so long ago. And until not so long ago, there would have been much discussion about Vaccari’s contemporaneity. All those who understand the contemporary as militancy that does not allow positions of recuperation even if in tune with one’s own time, or as pure and obsessive experimentalism (and it matters little, then, how vain and conformist it is), would have questioned themselves before his retrospective gaze, his ties with tradition, his recovery of an antiquated grammar. Vaccari is a contemporary painter in the first place because he lives, works and expresses himself in the present, a condition from which one cannot prescind. And then, we might add, his research was born in a historical moment in which outdatedness was a necessity: in the climate of affirmation of postmodernism, wrote Carlo Sala, "the recovery of diversity, including local diversity, and the reinterpretation of the visual tradition was favored in the conviction that a purely linear idea of the evolution of art history should be replaced with a circular vision that, while advancing, was able to collect and borrow some moments of that great deposit that is the visual culture of the past. This is the starting point of Wainer Vaccari’s research.

But Vaccari is perhaps even more contemporary than others if it is true what the Nietzsche of the Inactual Considerations argued, namely that he really belongs to his epoch who, in full awareness of the impossibility of escaping his own time and with the intention of not looking backwards with the gaze of the nostalgic, acts against the dominant myths and ideas and is therefore able to mature that detachment that allows him not to adapt, not to homologate and to offer a precise reading of contemporaneity. “Contemporaneity,” in Agamben’s words, “is a singular relation to one’s own time, one that adheres to it and, at the same time, distances itself from it; more precisely, it is that relation to time that adheres to it through a displacement and anachronism. Those who coincide too fully with the epoch, who match in every point perfectly with it, are not contemporary because, for that very reason, they cannot see it, cannot keep their gaze fixed on it.” Vaccari looks at contemporaneity with the detachment given by the discipline, culture and freedom of a painter who is not frozen in a rigid academicism (indeed, the opposite is true: recourse to the past arises from experience and necessity), who does not adopt tradition as if it were a shelter or even worse a fallback, but reads it, with his visionary accent, to question reality, to establish a space of painting in which the depths of passions, dreams, and memory are explored, where the elegiac and the grotesque, the distressing and the unusual, the domestic and the comic are intertwined. In short, where the theater of life, with all its uncertainties, enters the scene.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.