On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the restoration and new layout carried out by Carlo Scarpa (Venice, 1906 - Sendai, 1978) at the Museo di Castelvecchio in Verona in 2014, Alba Di Lieto and Alberto Vignolo edited and edited the publication Carlo Scarpa al Museo di Castelvecchio 1964 - 2014, produced in collaboration with the Order of Architects of the Province of Verona, to pay tribute to the famous architect, among the most important of the twentieth century, to whom we owe the current appearance of the Scaligera museum venue. Such an important anniversary for both the museum and the city could not, in fact, go unnoticed, given the scope and great value that the museographic and restoration work has meant, namely the creation of a reference model that has entered to all intents and purposes into architectural manuals, as well as a new approach to the restoration of monumental buildings. It is with this in mind that a book of recollections and thoughts was given to the press, involving artists, architects, art historians, museum directors and photographers who even just once came into contact with the museum set up by Carlo Scarpa. Particularly significant among the contributions is that of art historian Marisa Dalai Emiliani, who wrote: “Fifty years after the completion of the work, we do not cease to be amazed, with bated breath, by what I would call the uniqueness of the fate of the Castelvecchio museum: from the scandal of its modernity in 1964 to the scandal of its integral preservation in 2014. The secret: Carlo Scarpa’s project, his exemplary ”creative destructiveness“-as Nietzsche put it-in erasing, by intervening on a reality stratified for centuries, every trace of falsification of history, and vice versa, in laying bare and in value every original sign, against any form of contamination.” In the same vein is architect and lecturer Maria Grazia Eccheli, who finds “of unsurpassed mastery ”the Scarpa who removes,“ who proceeds by excavation,” the Scarpa who knows how to recognize “the genuine history of Castelvecchio in its connection with the city where it belongs”; regarding that “completely false” facade, Eccheli imagines that “the endless sketches, almost aniconic, stand as a testimony to all Scarpa’s anxieties in accepting that incomprehensible theatricality: a wall of a nineteenth-century barracks to which the stone elements of the rich palaces on the Adige were set.” Hence, the architect continues, “that skillful procedure toward abstraction that makes the facade a ’filigree’: cuts and detachments in search of a decisive truth.”

The 14th-century castle was built as a fortress, then took on the function of barracks and was transformed into a museum between 1924 and 1926 by Antonio Avena and Ferdinando Forlati to trace the history of Veronese art through ancient collections. It was finally in the 1950s, at the behest of the then director of the museum Licisco Magagnato, that the extraordinary restoration and layout designed and carried out by Carlo Scarpa was accomplished, giving back to the city a place that made its own history concretely visible. The official inauguration was held on December 20, 1964, but the construction site had begun several years earlier, in 1958. With the installation of Magagnato as director of the museum in 1956, a complex program of renovation of the Castelvecchio Museum was begun, especially from the structural point of view, and his choice regarding the expert architect to whom to entrust the renovation fell on the Venetian Carlo Scarpa who, already at the age age of fifty, had been responsible for the restoration and layout of some of Italy’s most important museums, such as the Gallerie dell’Accademia and Museo Correr in Venice, the Galleria Regionale di Sicilia at Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo, the Uffizi and Gabinetto dei Disegni in Florence, and the Gipsoteca Canoviana in Possagno.

On the strength of his great experience in the field of restoration and rearrangement and endowed with a strong sensitivity in his desire not to detach himself from the past, but rather to make it visible to all, and a connoisseur of the history of Verona’s monumental building, Scarpa proposed for the Scaliger castle an intervention that never in the history of architecture had any architect accomplished: as pointed out in their contributions by both Marisa Dalai Emiliani and Maria Grazia Eccheli, he decided to proceed by excavation and by destruction of at least some of those additions that had been made according to him unjustifiably and unjustly by Forlati and Avena’s first medieval-style intervention when, from barracks, the building was first transformed into a museum. In particular, he considered it a disarming falsehood to have used elements from the demolition of old palaces in Verona to transform the Napoleonic barracks into a Venetian palazzetto that more closely resembled nineteenth-century culture. With the elimination of these fake parts, Scarpa’s goal was to make visible the historical stratifications of Castelvecchio, highlighting the original appearance of the castle and all the subsequent portions belonging to different eras, precisely to emphasize the passage of time. He therefore proceeds by cuts and caesuras, bringing into play traditio and inventio. He makes cuts that make it possible to still read the successive stratifications of the building, creating, for example, open windows in the floor; he then connects the two main bodies of the castle, namely the medieval Palace and the nineteenth-century Gallery, and chooses the façade of the latter, equipped with a central loggia, as the entrance to the museum. The major courtyard where he places the main entrance to the museum building is laid out as a lawn.

It also gives rise to a unified museum itinerary: the visitor still has the feeling of taking one long walk along the rooms of the museum, in which indoor and outdoor parts follow one another in a continuum, the latter with the addition of staircases and suspended passages made using modern materials, in order to make it clear that they belong to modern times, to connect the structures that refer to different eras. In an overall vision, solids and voids are created in the Scaliger monument, interiors marrying with exteriors with the intention of happily linking the museum to the city. Moreover, at the point where the Reggia is connected to the nineteenth-century Gallery, Scarpa creates a system of metal walkways, within the void obtained by the demolition of the last span of the Gallery, and here he places on a concrete shelf the equestrian statue of Cangrande I della Scala, who smiles at the visitor, although in reality the condottiero never saw the castle, as the latter was erected almost two decades after his death by his great-grandson Cangrande II della Scala between 1354 and 1356. The Castelvecchio Museum is "a timeless work, an exemplum of the constructive power of architecture in its transfiguration of stones to the secret resonance of the Human,“ Eccheli writes. ”Will this be the reason for the Scarpian celebration, so strange at first glance, of Cangrande’s smile?"

Another element that makes the restoration work particularly significant is the idea of juxtaposing ancient materials, such as stone and wood, with modern materials such as exposed concrete or the use of ancient techniques revisited such as the colored stucco treatment of some surfaces. The use of different materials in the same environment can already be seen on the ground floor of the nineteenth-century part, in the sculpture gallery, which consists of seven large rooms that follow one after the other, accessed through evocative vaults, and which are illuminated by Gothic mullioned and three-light windows: on the ceiling a long iron beam, the walls of plaster, the floor of frattored concrete edged with Prun stone strips, and the interior surfaces of the arched vaults of pink Prun stone slabs. For each work exhibited in the gallery, the appropriate support was designed and, in particular, the extraordinary sculptural group of the Crucifixion by the Master of St. Anastasia, a soft stone sculpture from the first half of the 14th century, was placed at the end of the perspective view of the rooms. For this highly expressive sculptural group, which comes from the church of Saints James and Lazarus at the Tomb, the ancient lazaretto of Verona, Scarpa himself designed the current arrangement on a metal support that evokes in modern forms the cross on which Christ hangs and the two bases on which the Madonna and Saint John stand.

As for the Picture Gallery, which stretches along the second floor of the Gallery and the Palace, the architect chooses to place the works on stone shelves or on tuff cubes. A prominent role is to be attributed to lighting, or rather, to natural light, which according to Scarpa’s design was to appear homogeneous from all angles and was to emphasize the works while also taking into account the different materials of which they are made. As Maria Grazia Eccheli noted, “the changing of light seems to animate those stone characters, between recovered stones, unveiled stones and new stones, between stucco and concrete and water.” Scarpa has given birth to a physicality of his own.

What kicked off Carlo Scarpa’s work at Castelvecchio was the exhibition Da Altichiero a Pisanello, as director Licisco Magagnato entrusted him with the layout. The first phase of restoration then focused only on the Reggia, with cleanup, demolition and excavation work; in the second phase the Porta del Morbio, a city gate from the communal period, was uncovered, the last span of the Gallery was demolished, and the connecting point between the two parts was created, resulting in the placement of Cangrande, still one of the museum’s most characteristic symbols.

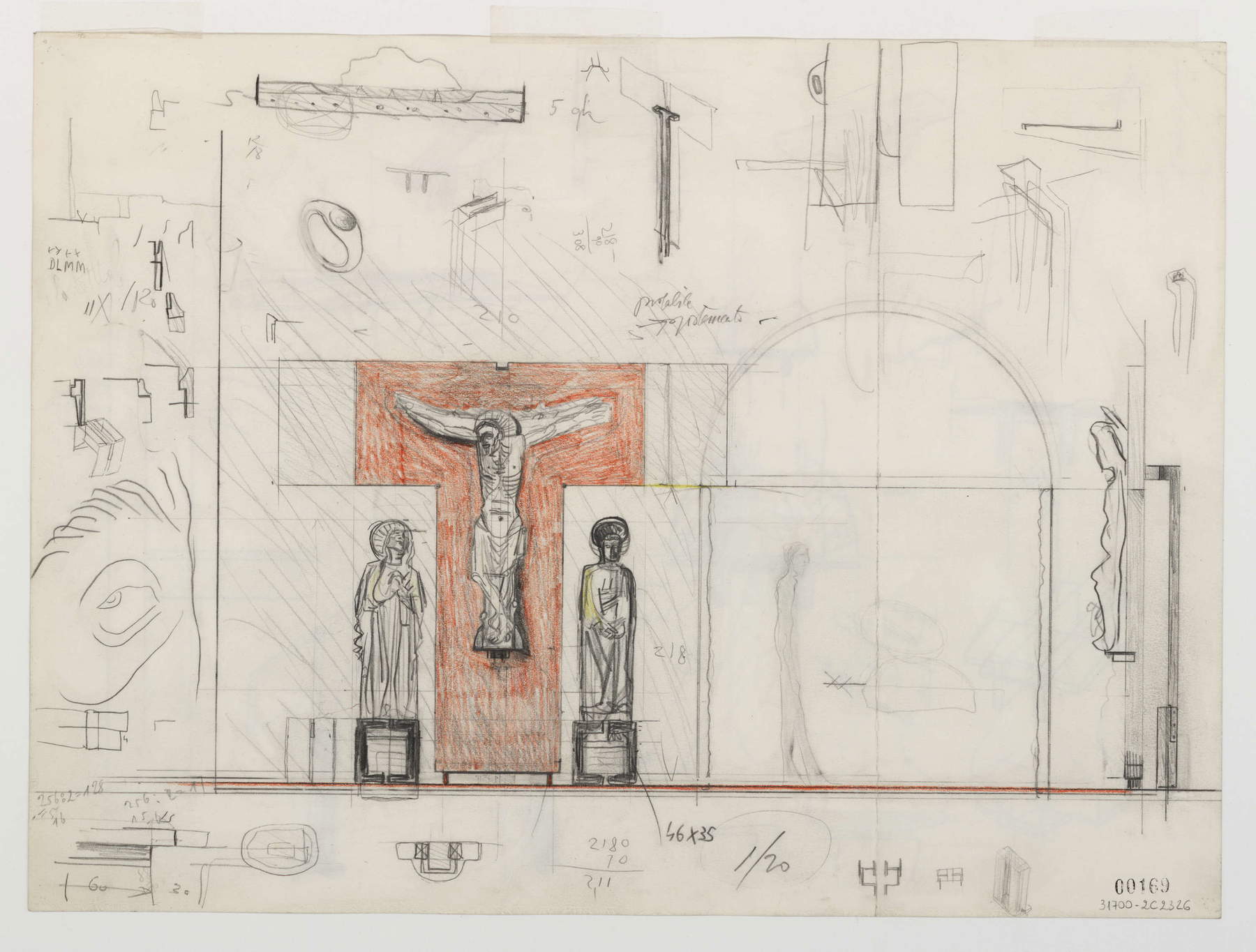

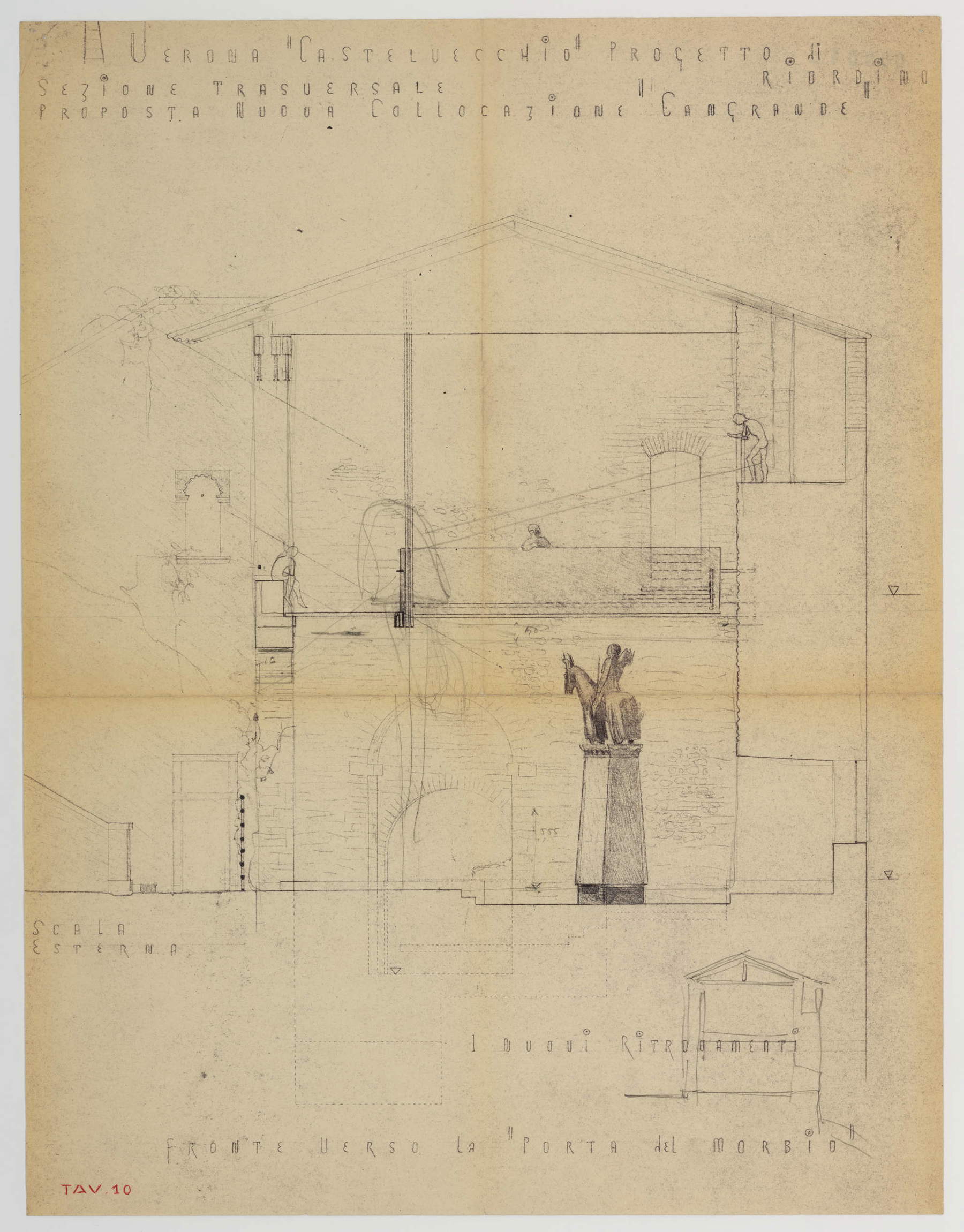

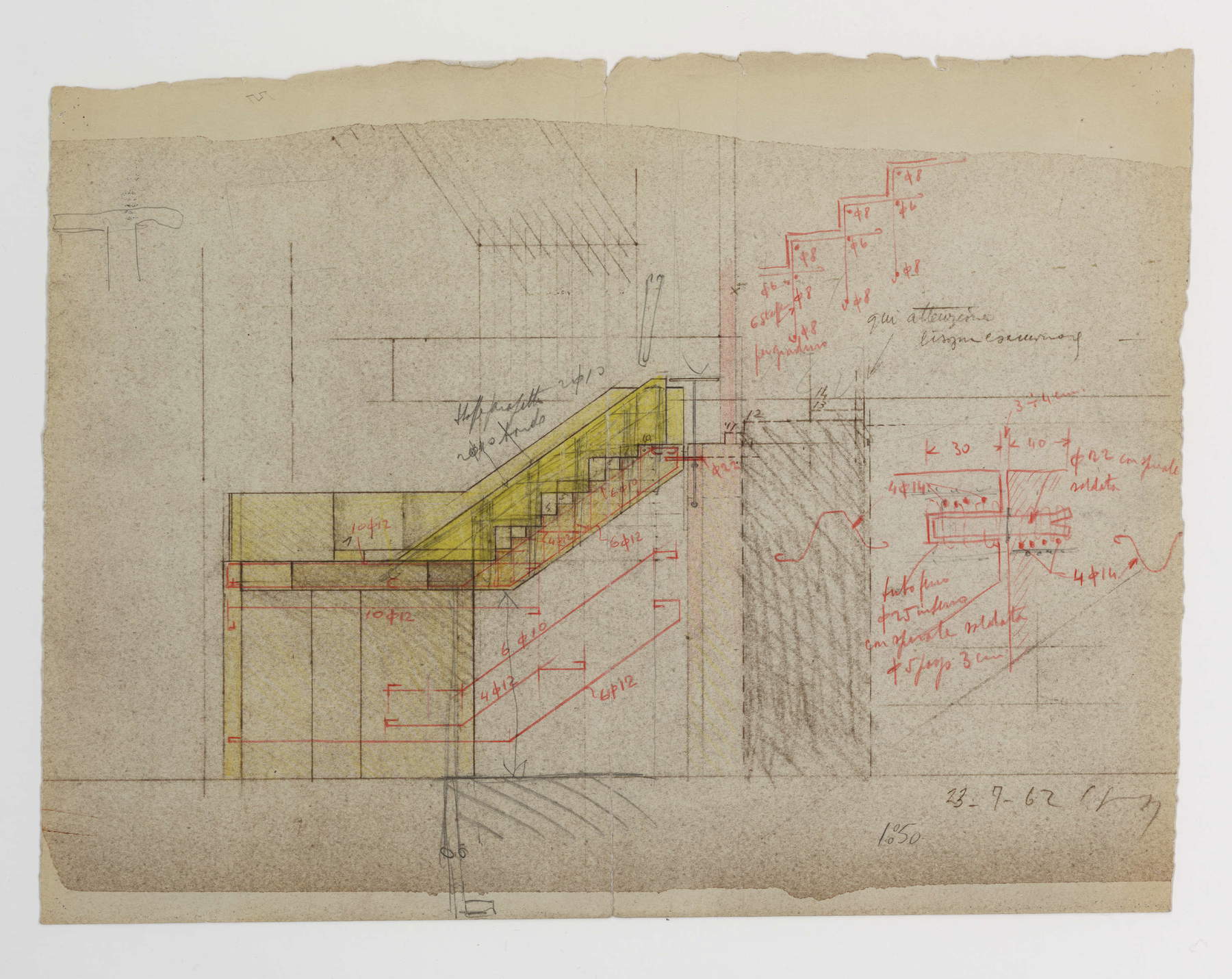

More than six hundred and fifty sheets, totaling 880 drawings, exist of this entire design, preserved in the Castelvecchio Museum and available online at the Carlo Scarpa Archive website. “I want to see things, I only trust this. I put them here in front of me on paper, so I can see them. I want to see, and for that I draw. I can only see an image if I draw it,” he had said. For him, in fact, drawing meant seeing reality, which was also useful in solving the difficulties that arose as the project was carried out. So these are drawings that represent fragments and details of the project.

The Castelvecchio Museum would not have been the museum it still is today without the overall intervention of Carlo Scarpa, which in turn is considered his greatest project, defining a true architectural model of a monumental building that confronts history in all its parts.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.