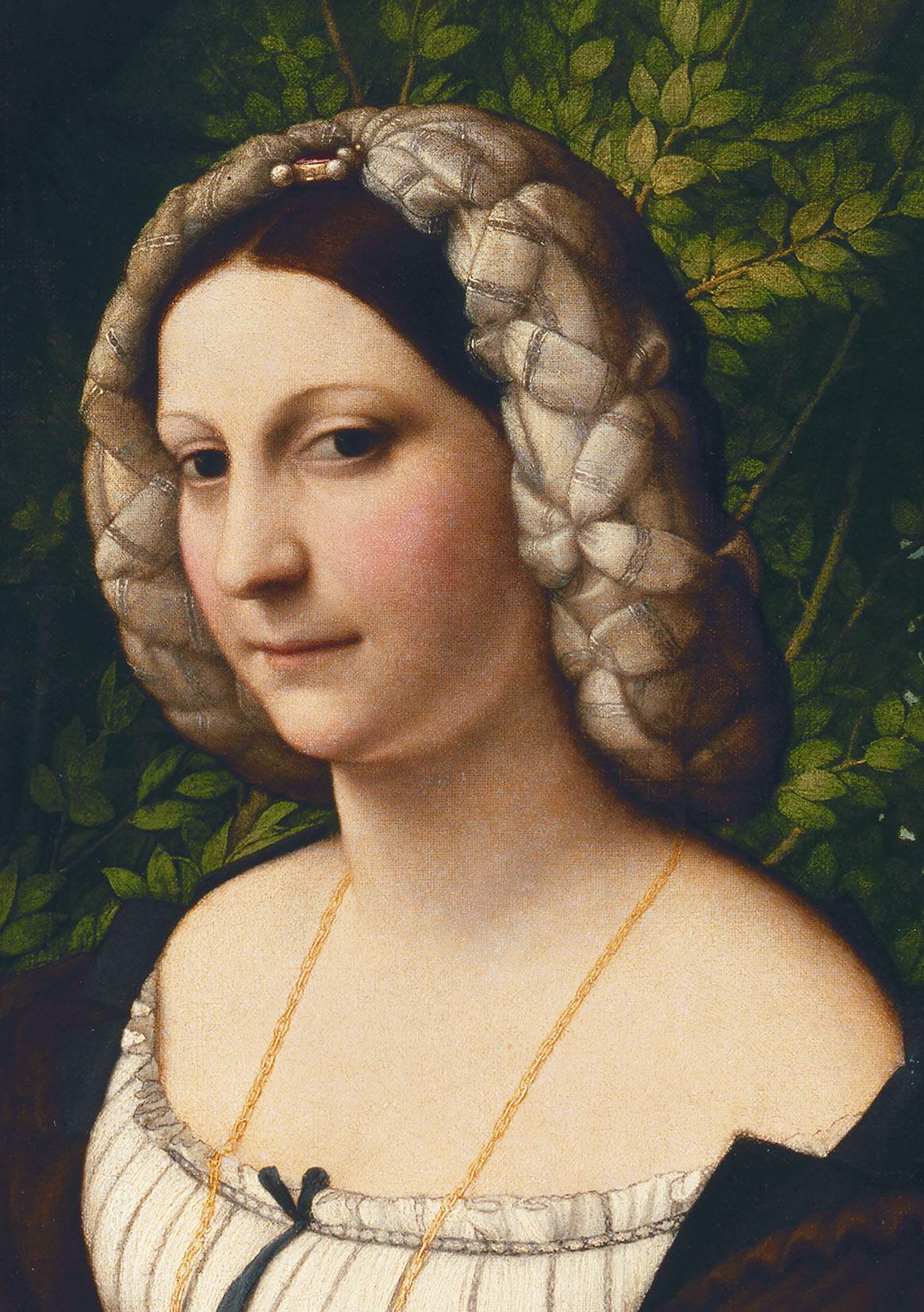

That she is a young woman of high rank is clearly discernible from the refined elegance with which she is dressed, the long necklace she is wearing and the jewel with a stone placed on her head, as well as theelaborate hairstyle she wears, but her identity remains undefined five centuries after it was painted. What is certain today is that the Portrait of a Young Woman executed around 1520 is the most important portrait by Antonio Allegri, known as Correggio (Correggio, 1489 - 1534), although in the past the painting was mistakenly attributed to Lorenzo Lotto. The authorship of the painting is confirmed by the artist’s signature in Latin, legible on the tree next to the gentlewoman: Anton. Laet., or Antonius Laetus, a designation Correggio used at the beginning of his career. In fact, at that time he often signed himself Antonio Lieto, Latinizing his surname into Laetus. The person who noticed the two Latin terms in the work was Ernst Friedrich von Liphart, a baron, painter, art expert and collector from present-day Estonia and curator of paintings at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg from 1906 to 1929, who wondered, “Quel est cet Antoine dont la dame fait la joie? Ce tableau appartient au prince Youssoupow” ("Who is this Antoine whom the lady makes happy? This painting belongs to Prince Jusupov); Liphart did not in fact understand who the Antony made happy by the lady was, according to the Latin block letters written in the lower left corner. However, there was no answer to that question, for later this interpretation was refuted by the famous art critic Roberto Longhi, who clarified that it should rather be understood, as already stated, as the Latin version of Antonio Lieto or Antonio Allegri. That wonderful portrait had thus been done by Correggio.

A native of the town of Correggio, where the painter was born, married, and died, and in whose court there was a lively cultural climate both humanistically and artistically, Antonio Allegri is considered a genius of the Italian Renaissance because of his intelligence and willingness in the continuous and in-depth study he loved to undertake in the most disparate subjects and above all for “his genius of formal creation and execution,” as Renza Bolognesi states in one of her essays.

Vasari, in his Lives, declared that “no one touched colors better than he did, nor with greater vagueness or with more relief did any craftsman paint better than he did.” Able to range from sacred to secular subjects, from easel work to noble frescoed rooms and vast church walls, the artist possessed a pictorial domain so broad and unique that no other Renaissance painter could match him. He was “glory to the art of all time and universal genius,” as David Ekserdjian reiterated.

|

| Correggio (Antonio Allegri), Portrait of a Gentlewoman (c. 1520; oil on canvas, 103 x 87.5 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

|

| Correggio (Antonio Allegri), Portrait of a Gentlewoman, detail of the face |

According to Giuseppe Adani, one of the best-known scholars and experts on Allegri, the “painter of the Graces” produced images of femininity that aroused wonder from his very beginnings: suave faces that he drew from the observation of reality and depicted with delicate features also thanks to his sensitive soul and his enchantment toward the fairer sex, a distinctive feature of his entire artistic production. In fact, Correggio throughout his career loved to depict the female body and this can be seen quite visually in the “enchanting and intensely expressive faces, hands and gestures, refined and sometimes extraordinarily elaborate hair styles,” so much so that Vasari himself was pleasantly impressed. Indeed, in his Lives, we read that Allegri made “such graceful hair, showing us such ease in the difficulty of doing it, of which all painters owe him eternally.”

The gentlewoman is shown seated in front of a tree, on the trunk of which a branch of ivy is wrapped; she is in the foreground, turned three-quarters to the viewer and gazing at him with a stately pose as she crosses her arms. She has brown eyes and hair, a fair complexion with slightly flushed cheeks, and is sketching a slight smile. Her hairstyle is very elaborate, but gathered by a braided ribbon cap, typical of sixteenth-century women’s fashion in northern Italy; an accessory that became popular thanks to Isabella d’Este, as seen in the latter’s famous portrait by Titian (Pieve di Cadore, 1488/90 - Venice, 1576). Her clothes are loose and luxurious, offering a soft feel, and have a white part and a part, above the latter, of a dark brown color. She wears a long gold-colored fine necklace and holds a silver cup with her right hand, offering it to the viewer, while with her left hand she moves a flap of her wide sleeve. Behind her, a verdant landscape can be glimpsed.

In Correggio’s production, portraits are very rare; however, a famous one comes to mind, the Portrait of a Man with Book kept in the Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco and made in about 1522, which shows the subject in a graceful pose, as elegant and graceful is the Portrait of a Young Woman. It is no coincidence that these are the years just before the first edition of Baldassarre Castiglione’s The Courtier, published in 1528, but which the man of letters was working on from 1513 to 1524, so themes of grace and courtesy, especially in court circles, were quite frequent.

|

| Titian, Portrait of Isabella d’Este (1534-1536; oil on canvas, 102.4 x 64 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

|

| Correggio (Antonio Allegri), Portrait of a Man with Book (c. 1522; oil on paper fixed on canvas, 60.2 x 42.5 cm; Milan, Castello Sforzesco, Pinacoteca) |

|

| Raphael, Portrait of Baldassarre Castiglione (1514-1515; oil on canvas, 82 x 67 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

The silver cup that the woman holds in her hands also shows a peculiarity, or rather a detail on which the various hypotheses regarding the identification of the personage have been built; on the inside, in fact, one can read the Greek inscription Nepenthes. Once again Ernst Friedrich von Liphartsimade a discovery about the painting, for it was he who linked the inscription to theOdyssey, specifically to the fourth book, where the term nepenthés appears for the first time. This is the passage in which Telemachus, who had embarked in search of his father Odysseus, arrives in Sparta at the palace of Menelaus and Helen; the atmosphere of commotion common to all present because of the memory of the war, the mourning and the fate of Odysseus himself causes Helen to decide to dissolve in the wine they were to drink precisely the nepenthhes which had the property of driving away sorrow: “But into other Thought then Helen entered. / In the sweet wine, of which they drank, drug infused / Contrary to weeping, and wrath, and which oblivion / Seco inducea d’ogni travaglio e cura.”

As mentioned above, the identity of the young woman has not yet been recognized: in fact, this is one of the most debated aspects of the work, in addition to that of its commissioner. First, Roberto Longhi advanced the hypothesis that the woman portrayed was the poetess Veronica Gambara (Pralbonio, 1485 - Correggio, 1550), to whom the laurel bush behind her would allude, as a symbol of poetry; Veronica Gambara was a fine poet appreciated by Pietro Bembo (Venice, 1470 - Rome, 1547) and wife of the lord of Correggio, Gilberto X da Correggio, who was widowed by the latter in August 1518. Veronica Gambara was supposed to have been the painter’s “natural patroness,” as to soothe the pain of recent bereavement she may have ingested nepenthes; her status as a widow could also be confirmed, according to Longhi, by the “brown cloths,” by the “scapular,” which according to one belief was given by Our Lady of Mount Carmel to Saint Simon Stock to free him from the pains of Purgatory, and by the “cordiglio of a Franciscan tertiary.”

From sixteenth-century sources, however, it appears that Gambara was of sturdy build and not very graceful, so, following these records, Correggio scholar Riccardo Finzi rejected Longhi’s idea and advanced the hypothesis that the one depicted was Ginevra Rangone ( ?, 1487 - Castiglione delle Stiviere, 1540), another noblewoman of Correggio’s milieu, also widowed by Giangaleazzo da Correggio in 1517 and also a Franciscan tertiary.

|

| Correggio (Antonio Allegri), Portrait of a Gentlewoman, detail of the cup |

Although Veronica Gambara and Ginevra Rangoni were both for a long time the two most likely gentlewomen for identification, the name of another widow, Laura Pallavicino Sanvitale, wife of the lord of Fontanellato, Gianfrancesco Sanvitale, who died in 1519, has also recently been advanced; in this case, the presence of the laurel would refer to the woman’s name, Laura.

Neither of these identities has so far been confirmed, partly because it is now thought that in nepenthes does not actually refer to widowhood, but to the more likely interpretation that the “drug” is in an allegorical sense dialogue and the ability to cheer guests through a kind of moral support: the gentlewoman then would be a model of religiosity and the ability to relate to others through learned dialogue. And the interpretation of the widowed state was thus overcome as there are no symbols in the work that hint at this: no wedding ring and the clothes reflect the fashion of the early decades of the 16th century.

As for the collecting vicissitudes, Liphart was right who had stated, “Ce tableau appartient au prince Youssoupow”; indeed, the earliest evidence concerning the painting refers to the collection of Prince Nikolai Borisovič Jusupov of St. Petersburg who had purchased it from the Venetian merchant Pietro Concolo. The painting became part of the Jusupov collection from 1837, and from 1918 to 1924 it remained in the family’s palace-museum; from there it came to theHermitage in 1925, where it is still preserved.

However, thanks to the extraordinary loan from the famous St. Petersburg museum, until March 8, 2020, the Portrait of a Young Woman is on display in Reggio Emilia, in the Cloisters of St. Peter’s, and in conjunction with this event, there will also be an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of how women dressed, bejeweled, and combed their hair in the early 16th century and how ornamentation has developed up to our own time, in the exhibition What a wonderful world. The Long History of Ornament between Art and Nature, hosted in the two venues of Palazzo Magnani and the Cloisters of St. Peter’s.

An extraordinary loan and an unprecedented exhibition linked by two seemingly unrelated but actually close aspects: art and fashion.

Bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.