Giacomo Balla (Turin, 1871 - Rome, 1958) was one of the leading exponents of Futurism, but also the one most closely linked to the Divisionist matrix. At first linked to a more traditional social painting style, he soon became linked to the Futurist avant-garde in which he assumed a fundamental role. He had strong ties with Umberto Boccioni and Fortunato Depero, with whom he established an artistic dialogue that allowed him to abandon realist painting and veer toward avant-garde artistic pursuits. Balla, who was a man of eccentric character and very self-confident to the point of comparing himself to great masters such as Titian and Leonardo, was also a great artist capable of expressing his ideas not only on canvas but also in film, music and furniture.

The artist from Turin was also greatly appreciated by the Fascist regime , which Balla saw as the road that would lead Italy to modernity. Around the 1930s, however, Giacomo Balla, who was one of the most passionate promoters of Futurism broke away from it to return to figurative painting, which he said was the one that best approximated reality. His detachment from Futurism also sanctioned his detachment from Fascism, which caused him to be shunned by official culture. After the war, however, his work would be greatly reevaluated.

|

| Giacomo Balla |

Giacomo Balla was born in Turin on July 18, 1871, to Giovanni and Lucia Giannotti. Giacomo was orphaned by his father when he was only nine years old: however, his mother invested all her energy and earnings in her son’s education. Even at an early age Giacomo showed uncommon artistic flair: first he began studying violin, which he abandoned after a short time to devote himself to painting. After finishing high school he enrolled at theAccademia Albertina in Turin, where he had the opportunity to study perspective, anatomy, and geometry. Soon he also began to attend lectures by the famous anthropologist and criminologist Cesare Lombroso. It was at the Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts that Balla made his debut in 1891. In addition, the environment was frequented by the Turin aristocracy and upper middle class, and it was here that he met the writer Edmondo de Amicis and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, a young artist who became one of the leaders of Italianpointillism.

In Turin, artists were greatly influenced by verista descriptive painting, marked by a strong ethical and social commitment that characterized Turin culture at the turn of the century. In 1895 Balla left his hometown forever to move to Rome with his mother, where he remained for the rest of his life. In the capital, Balla presented himself as a pioneer of Divisionist technique and immediately found pupils ready to follow him: among them Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini and Mario Sironi, whom Balla got to know at the Nude School in Via Repetta in Rome. In this early Roman period he painted some of his masterpieces such as La Pazza (1905), which carries with it the kind of verista painting aimed at sociality that Balla did not renounce. In 1903 he exhibited at the 5th Venice Biennale: it was the first of many subsequent participations. In 1905 he married Elisa Marucci and from their union was born their first daughter, Luce, who would later become a Futurist artist.

Meanwhile, the poet and painter Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published the Manifesto of Futurism in the French newspaper "Le Figaro" in 1909. Marinetti’s goal was to create an artistic-literary avant-garde capable of overcoming stagnant Italian culture. Forgetting the past and looking to the future-this was the movement’s cardinal principle. Balla joined the new Futurist movement, although he was the oldest and was already considered a master of pointillism. In 1910, thus only a year after the first Futurist manifesto was published in Paris, the Manifesto of Futurist Painting was published in the Italian magazine Poesia, and among the signatures appeared those of painters Umberto Boccioni, Luigi Russolo, Gino Severini, Carlo Carrà, and Giacomo Balla . The text was written on the spur of the moment, after Marinetti inflamed the spirits of the painters adhering to the new movement. In 1912 an exhibition of Futurist painters was held in Paris at Galerie Bernheim - Jeune, in whose catalog Balla’s work Lampada ad arco (1911) was also mentioned. For the dissemination of the new ideas the manifesto presented itself as the best tool, and between 1909 and 1916 about fifty were drafted, which from time to time dealt with different themes, such as music, cinema sculpture and architecture. During this period Balla painted some of his masterpieces, such as Child Running on a Balcony and Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912). These were years of great creativity for Balla, who shifted his research from a realist language typical of the turn of the century to an avant-garde artistic pursuit that also allowed him to play a more active role within the Futurist group. These were also the years of the Great War, which was strongly supported by Balla and the Futurists.

In 1915, Balla signed together with Fortunato Depero the Manifesto of the Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe, according to which pictorial dynamism and plastic dynamism are connected to “the art of noises” and to “words in freedom,” that is, the words that make up the text have no grammatical or content connection whatsoever. The idea of ’total art continued throughout World War I, and when Umberto Boccioni died in 1916, Giacomo Balla was the undisputed protagonist of the movement, to the point that he began to sign his works under the pseudonym Futurballa . In 1921 he painted parts of the cabaret club Bal TicTac in Rome where jazz was played. Balla adhered to fascism, in fact in 1926 he made a statuette depicting Mussolini, which was given to him. Giacomo Balla thus became the artist of fascism and was also highly regarded by critics. In 1925 Balla participated with Depero and artist Enrico Prampolini in the Paris Exhibition of Decorative Arts. The Manifesto of Futurist Aeropainting, which he drafted in 1929, marked his last act of adherence to Futurism, as during the 1930s he dissociated himself, in the belief that “pure painting” could be discovered in realism. From then on, his works were characterized by figurative painting. Giacomo Balla died on March 1, 1958, in Rome.

|

| Giacomo Balla, The Girlfriend at the Pincio (1902; oil on panel, 60.5 x 90 cm; Milan, GAM) |

|

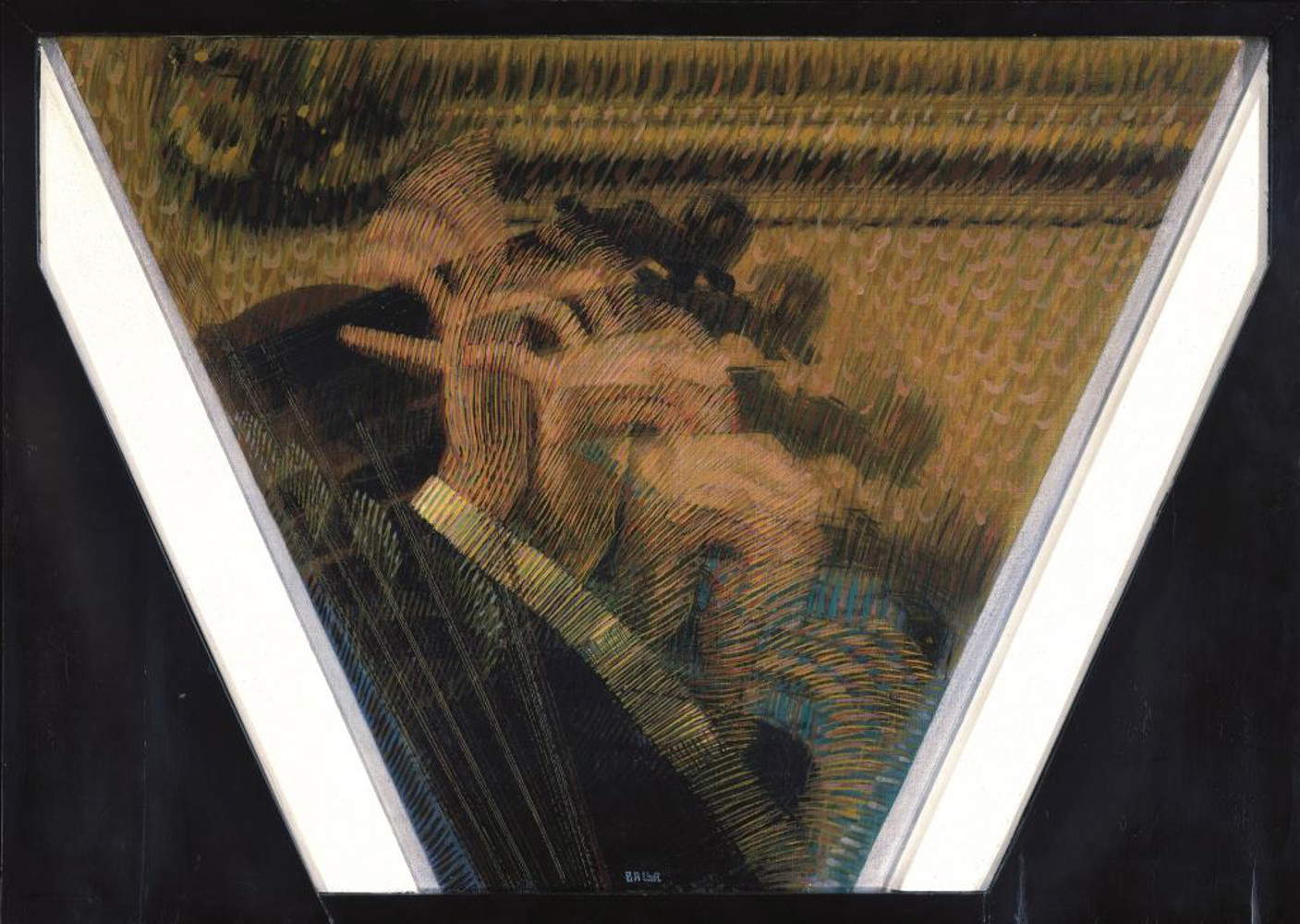

| Giacomo Balla, The Violinist’s Hand (1912; oil on canvas, 56 x 78.3 cm; London, The Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art) |

|

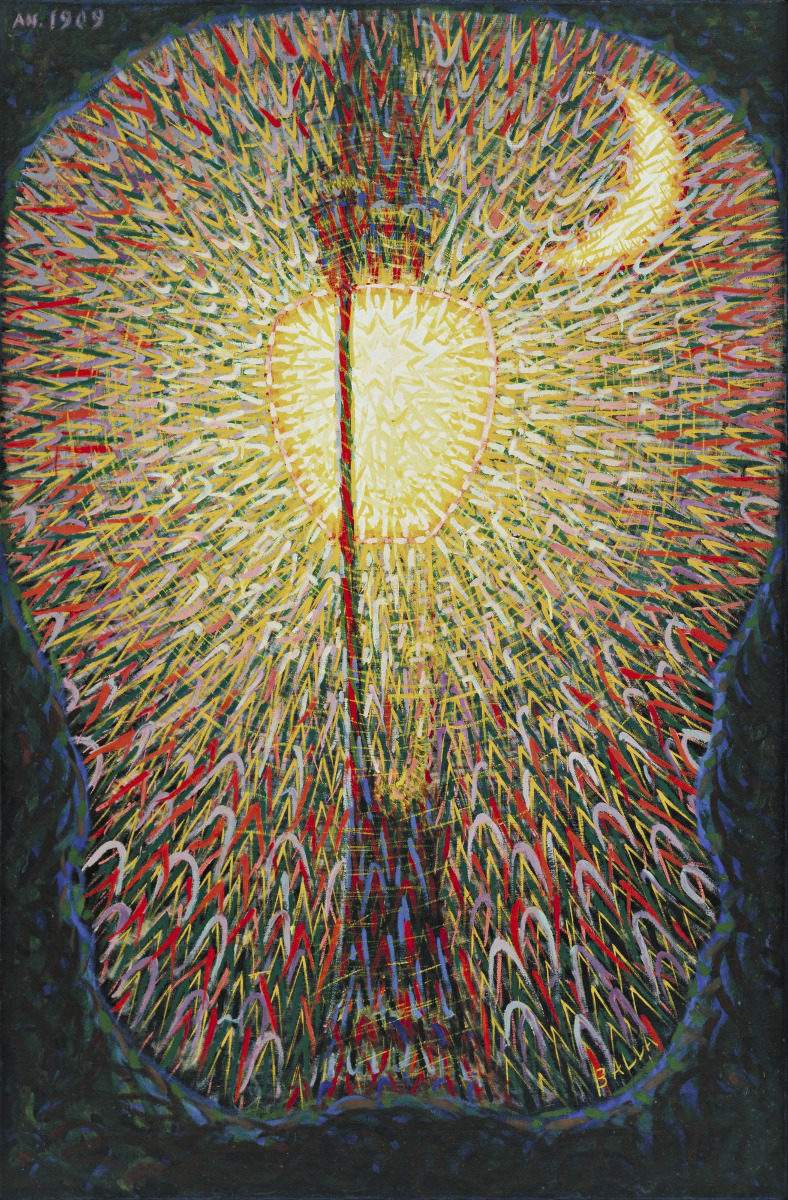

| Giacomo Balla, Arc Lamp (1909-1911; oil on canvas, 174.7 x 114.7 cm; New York, Museum of Modern Art) |

From the beginning of his painting career until his adherence to Futurism, Giacomo Balla’s painting was characterized by precision and an approach to the canvas very close to the photographic approach: “simplicity is the basis of beauty,” he had to say, and this was the principle on which his painting was based. The painter was interested in the principles of science, and therefore objectivity was the basis of his artistic pursuit.

As mentioned, Balla’s early works were characterized by a Divisionist type of brushstroke, and the work La fidanzata al Pincio (1902) bears witness to this: the viewer’s eye immediately rests on the figure of the solitary girl immersed in the nature of a Roman garden. The girl wears a white blouse and blue skirt, and her face expressing solitary meditation rests in the palm of her hand. The flowerbed behind the figure is bordered by small wooden posts, and a portion of a tree trunk can be glimpsed at the top. Finally, a white path frames part of the canvas continuing to the top.

A canvas of a more impressionistic character given both the subject depicted and the composition was Portrait of a Lady in the Open Air (1903). The work also corresponds to what painter Pellizza da Volpedo explained in an 1898 letter that the workmanship of the work varies according to how the subjects are in nature and that the colors and forms must achieve a "speaking harmony ." In fact, Pellizza’s idea is rendered in visual form by Balla through the freer brushstrokes in the subjects portrayed in the foreground and the architecture in the background that is simplified, thanks in part to the use of thepointillisme technique (a painting technique that is based on the decomposition of colors into small dots). In the painting, the female figure is depicted standing and facing sideways; behind her shoulders and the sparse vegetation is a landscape. The National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome houses one of the Turin painter’s most important works: it is the Polyptych of the Living: The Madwoman. The work is part of the cycle of the Living, which includes four different subjects on separate panels: The Madwoman, The Sick, The Peasant and The Beggar. The four panels depict the four different conditions of the misery of human life. In the work La pazza (The Mad woman) Matilde Garbini, the painter’s neighbor, was depicted facing the door appearing visibly troubled by psychic illness: the convulsive gesture of the hand she brings to her mouth intimating silence, her left arm appears tense and nervous, and her clothes hint at a thin and unkempt body, all revealing the woman’s psychic condition. Behind the female figure stretches an agricultural landscape. It is interesting to note how in the verso of one of the canvases appears the inscription “first electrical treatment by Prof. Ghilarducci - the man has the right side paralyzed, the woman suffers from neurasthenia - painting executed in the ambulatory always from life - year 1903 - Balla.” This notation is evidence of Balla’s interest in marginalized people: an involvement that can also be traced back to the research of anthropologist and criminologist Casare Lombroso, with whom Balla came into contact during his time in Turin.

The subjects of the canvases changed in the following years, a consequence of the painter’s joining Futurism in 1909. Portraits with the verist flavor typical of the 19th century were no longer depicted: instead, his interest shifted toward modernity, so celebrated by the Futurist painters, and toward the "myth of electricity." Demonstrating this shift very well was the painting Arc Lamp (1909-1911). The work was bought by the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1954, and when it was sent overseas Giacomo Balla also enclosed a letter to the then director Alfred Hamilton Barr Jr, speaking of the work as follows: “Painting, besides being original as a work of art, also scientific because I have tried to represent light by separating the colors that compose it. Of great historical interest because of the technique and the subject.” These brief lines reveal not only the eccentricity that characterized the painter throughout his life, but also the overwhelming interest in progress of which Balla and the Futurists were great advocates. The pointillist stroke is used here to break down light into its individual parts: in the center a lamp is supported from above by a metal structure, and to the side is depicted the moon, which Balla deliberately makes shine less brightly than the lamp, exalting electricity and more generally progress and science, all of which were part of the modernist poetics of Futurism. In 1912 Balla definitively moved away from realist painting and executed the famous canvas The Violinist’s Hand made through a dynamic decomposition of movement that not only testifies to Balla’s interest in photography (a passion passed on to him by his father), but also to the influence of Boccioni’s ideas. The work describes the fast movement of a hand and the optical effect this movement produces. From the same year is the work Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash: dynamism was one of the Futurists’ main concerns. The painting depicts a woman and her small dog, both made with quick dark brushstrokes against a white background that enhances dynamism and movement.

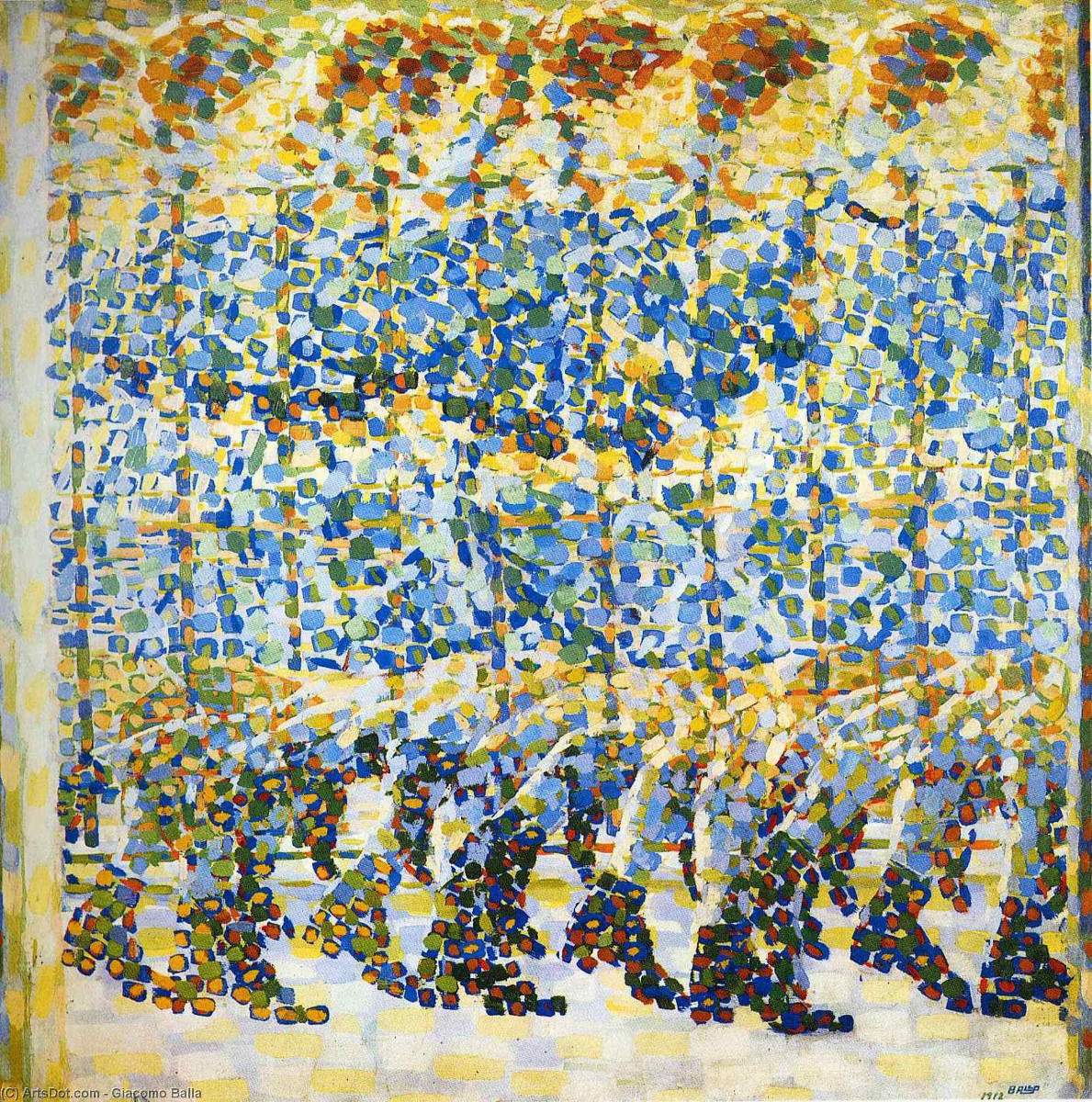

It is necessary to point out that this kind of dynamic approach of the figures represented also derived from the interest in photodynamics (reproduction of movement in photography), of his friend and photographer Anton Giulio Bragaglia, to whom Giacomo was very close and fond. Balla and the Futurists gave much importance to the concepts of dynamism and speed: this attitude was taken on the one hand as a reaction to the static nature of Cubism, and on the other hand because Futurism saw in the animated perception of things the only correct way to know reality. In the Girl Running on the Balcony (1912) the movement of running is here fragmented and broken down into instants that are blocked and isolated by the arist’s brushstroke. Balla, in this painting, depicted his first daughter Luce: the figure is barely perceptible; one can recognize the hair, the face and the running of little Luce. Each of these elements was “multiplied” horizontally to give back to the viewer the movement of a running child. Balla turned his scientific interest not only to movement and dynamism but also to the perception of light and color, which the painter translated into an abstract, non-naturalistic manner. Iridescent Compenetration No. 7 is part of a larger study of the play of light and color as the human eye perceives them. The Compenetrations represented one of the highest moments of Balla’s artistic research during these years (1912-1913). The compositional method that the Turin artist adopted, in some cases, was that of the decorative pattern that was repeated in modular sequences, or a pyramidal pattern that refers to the propagation of magnetic waves. Speed of the Automobile (1912) was the visual expression of the manifesto Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe published in 1915. Painting becomes a set of signs that aims not so much at the depiction of the object as at its interpretation. In Velocità d’automobile he does not see the car: if anything, it is the brushstrokes that by breaking down and fragmenting the object restore the feeling of the car’s dynamism. Balla’s work, based on knowledge of things, abandoned the criterion of painting “what is seen” in order to exalt "what is thought ." This aspect is fundamental to understanding Balla’s art. In the work Rapid Movements: Moving Paths + Dynamic Sequences Balla depicted a study of landscape in motion. The painter was convinced that the idea of painting the traditional landscape was untrue since everything in nature moves: the streams of water, the clouds, the foliage of trees, and the birds flying. To capture movement, then, is nothing more than to capture the fundamental principle of nature. In these works, the title takes on a fundamental aspect since the viewer does not possess the tools through which the artist expressed his vision, so it becomes necessary to complete the work and makes the subject explicit, as in Andal Lines + Dynamic Succession whose title refers to the study of the motion of a swallow’s flight.

In the post-Futurist paintings (1930s) Giacomo Balla returned to figurative painting by relying on bright, bright coloring, as demonstrated by Primo Carnera (1933) found on the verso of the work Perfume Expansion. The portrait of boxer Primo Carnera is evidence of this return to figurative painting. The subject of the painting was one of the most well-known icons of the time, a sports celebrity and example of manhood. What is interesting is the fact that Balla decided to restore in painting the aura that surrounded the famous boxer, and although it is not possible to read explicitly a precedent of Pop Art, it is nevertheless essential to highlight Balla’s originality that although he returned to a traditional painting he did not recover classical subjects, as other artists of this period did: Balla preferred to follow more contemporary paths.

|

| Giacomo Balla, Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912; oil on canvas, 91 x 110 cm; Buffalo, Albright Gallery) |

|

| Giacomo Balla, Girl Running on a Balcony (1912; oil on canvas, 125 x 125 cm; Milan, Museo del Novecento) |

|

| Giacomo Balla, Iridescent Compenetration No. 7 (1912; oil on canvas, 77 x 76.7 cm; Turin, GAM) |

Most of Giacomo Balla’s works can be seen in Italy: at the Galleria Nazionale d’arte Moderna are La pazza (1912), Villa Borghese - deer park (1910), and Ritratto di Signora all’aperto (1903). At the Galleria Civica d’arte moderna e contemporanea you can admire the series Compenetrazione iridescente No. 7 and No. 13 from 1912. At the Museo del Novecento in Milan the work Ragazza che corre sul balcone (1912) can be seen.

On the other hand, at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice is Mercury Passes Before the Sun (1914), Moving Lines + Dynamic Succession (1913) and Abstract Speed + Noise (1913-1914). The work Automobile Speed + Light is kept at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden. In contrast, the Museum of Modern Art in New York has Rapid Movements: moving paths + dynamic sequences (1913), Automobile Speed (1912) and Arc Lamp (1909-1911), while Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912) is in Buffalo at the Allbright-Knox Art Gallery.

|

| Giacomo Balla, the futurist of dynamism and light effects |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.