A seemingly unusual building technique, far removed from the usual architectural focus of the Minoans, emerged clearly in the 2025 excavation campaign of the Palace of Archanes, at Tourkoyeitonia on the island of Crete , Greece, at the center of the modern settlement. The research, directed by Effie Sapouna-Sakellarakis and resumed in 2023 after a long interruption, aimed to complete the picture of the large three-story building that thrived until 1450 B.C., the phase in which it suffered final destruction.

The investigation focused on the study of a previously known but never convincingly interpreted feature: a double, sloping wall that enclosed a large portion of the central courtyard. The structure, built of unworked stones and lacking any surface care, had raised doubts because of its apparent inconsistency with the quality of the rest of the complex. Analyses conducted with the support of specialists, however, made it possible to define its purpose: the wall was a protection against the risk of landslides from the rocky slope above. It is precisely this function that explains the scant attention paid to the southern sector, facing the non-visible area of the courtyard. The desire to avoid aesthetic contrasts within the courtyard led the Minoan builders, however, to construct a second wall adherent to the first, carefully lined with limestone blocks similar to those used in the rest of the palace. The intervention provided a regular front consistent with the architecture of the building, confirming how practical needs and formal research coexisted in Minoan construction sites.

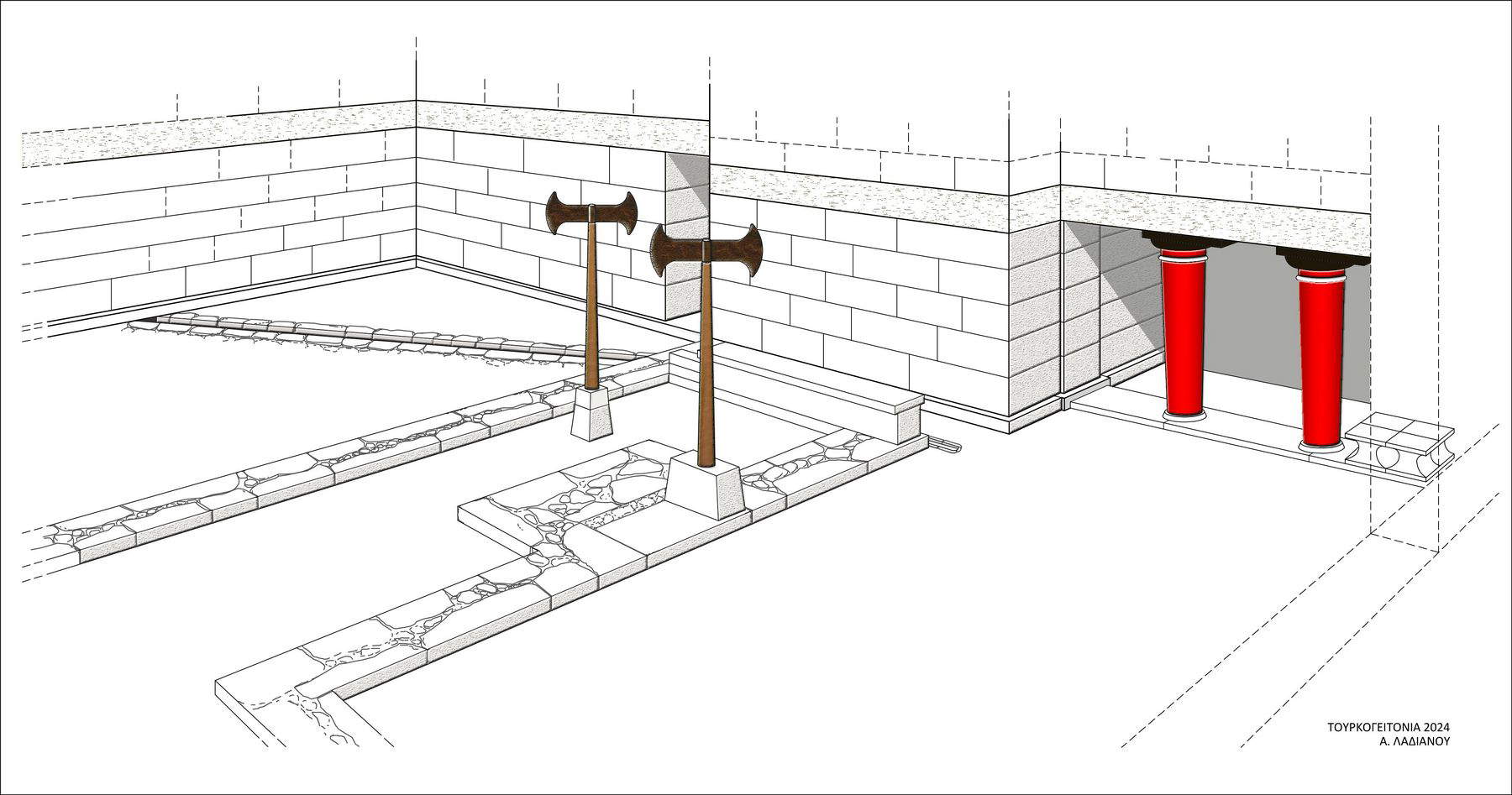

Layers typical of the Mycenaean phase were identified above this structure, with a large number of wine cups(kylikes), and materials from the historic period. The most representative objects from the long frequentation of the area include a Hellenistic three-lobed wine or water jug-like vessel(oinochoe) with two heads in relief, datable to the 3rd century B.C., and a clay head once applied to an unpreserved artifact. In the southeastern area of the excavation, work uncovered new elements useful for understanding the internal circulation of the palace. In so-called Area 28 , a passageway from the central court to the eastern sectors of the complex was identified. Two stone slabs divide the room into two parts; on them rested a large trapezoidal block equipped with lathes, likely the base of a parapet later destroyed by a Mycenaean-era wall. From the same context comes a fragment of natural stone with vaguely anthropomorphic features, which fell from an upper floor and can be traced back to a small votive shrine, similar to that attested at Knossos. The 2023 and 2024 campaigns had already offered revealing elements on the distribution of rooms in the northern area, where two- and three-story rooms belonging to a high-ranking wing were identified. Here rooms connected by corridors emerged, with plaster thresholds, fragments of frescoes, plaster-covered walls, and shale floors. In many rooms the usual bands of plaster that framed the floor slabs remained in situ.

The site of Archanes, frequented without interruption over the centuries, had been destroyed around 1700 BC by a violent earthquake, but rebuilt and expanded until the mid-15th century BC. The earliest reports about the locality date back to Sir Arthur Evans, who identified materials from the nearby Minoan necropolis of Fourni, later systematically explored by Yannis and Efi Sakellarakis, revealing five tholos tombs (circular constructions) and numerous funerary structures, including cist burials of Mycenaean age. In the center of the present settlement Evans had also identified wall remains and excavated a circular aqueduct, believed to be part of the complex. However, it would be Yannis Sakellarakis, through reconnaissance and investigations in the basements of modern houses, who demonstrated that many dwellings rested on Minoan masonry not recognized by earlier scholars such as Marinatos and Plato, who had searched without results for the summer palace hypothesized by Evans. Mapping the remains thus made it possible to locate the center of the palace, revealing monumental structures and objects of high craftsmanship; an archive and theater space were also identified in an adjoining area. The 2025 campaign was conducted by the Archaeological Society, with the participation of archaeologists Polina Sapouna-Ellis, Dimitris Kokkinakos, Persefoni Xylouri, planner Agapi Ladianou, restorer Veta Kalyvianaki, and photographer Kostas Maris. A key contribution came from geologist Charalambos Fasoulas, who clarified the function of the sloping wall.

In addition, the inclusion of Zominthos, discovered on Mount Psiloritis by Yannis Sakellarakis and excavated together with Efi Sapouna-Sakellarakis, in the UNESCO World Heritage Site is a recognition of the overall value and Minoan identity of Crete. Accommodation has been provided in and around the archaeological area, including parking lots, a guardhouse, toilets and information panels. The inclusion was, as is known, along with five other Minoan palaces: Knossos, Phaistos, Zakros, Mallia and Kydonia. It should also be noted that small museums or information centers have been set up at both Archanes and Anogeia, devoted entirely to finds from the excavations at Archanes, Zominthos, and Idaion Andron, respectively.

|

| Discovered the function of the double wall of the Minoan palace in Crete. Here's what it was used for |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.