A new exhibition on Battistello Caracciolo, articulated between the Capodimonte Museum, the Royal Palace, and the Certosa di San Martino, has opened in Naples: more than an exhibition, it is a true immersion in the Neapolitan seventeenth century. The itinerary unfolds mainly in the Raphael Causa room of the Capodimonte Museum, where about eighty painted canvases by the artist will be on display until October 2, 2022. Thus, with this event, the string of exhibitions focusing on Neapolitan artists or those linked to the city, which has included shows on Luca Giordano, Vincenzo Gemito but also Caravaggio, Santiago Calatrava, Jan Fabre and Picasso (with his fleeting stay in the city), continues.

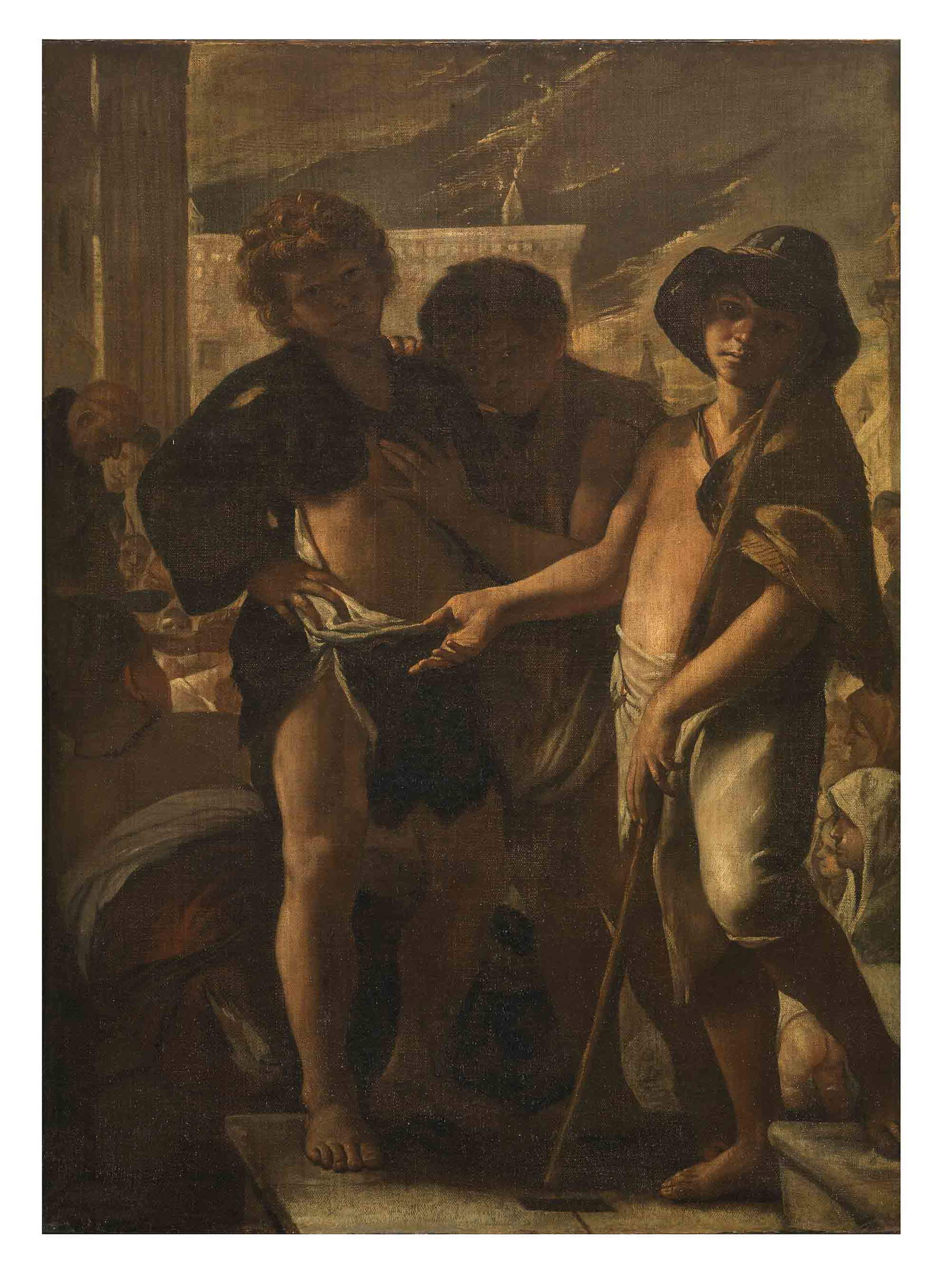

Born in Naples in 1578 and dying in the same city in 1635, Giovan Battista Caracciolo, known as Battistello, was to be one of the protagonists of the season of naturalism in 17th-century viceroyal Naples, whose greatest exponent was Caravaggio. Many of Caracciolo’s works cannot but often recall the very works of Merisi, with comparisons often suggested precisely by an intelligent museum itinerary.

Battistello Caracciolo was “discovered” by Roberto Longhi in 1915, immediately highlighting his relationship as a “follower” of Caravaggio and calling him a “bronze patriarch of the Caravaggeschi.” It is precisely bronze, the shade much used by Caracciolo, that also characterizes the exhibition layout. Again, it is impossible not to compare the itinerary to that of the 2018 Caravaggio Napoli exhibition in the same Causa hall of Capodimonte. While then the visitor explored the exhibition in the darkness illuminated only by the glow of the paintings, for this exhibition instead the exhibition spaces, although characterized by a similar path, were marked by a bronze hue, symbolizing somehow a continuation from the path of Caravaggio himself, but at the same time also a detachment.

As noted by Professor Stefano Causa, Battistello was about as close to a pupil as Caravaggio could get, but at the same time he departed from him considerably: an “infidel Caravaggesque.” In fact, Battistello was to be a great user of drawing, as well as an artist accustomed to frescoing and engraving, unlike the Lombard master who, as is well known, in addition to devoting himself only to painting, did not use preparatory schemes, capturing the naturalism of his models from life. With this in mind, the corridor of drawings takes on particular importance, underscoring this major difference with Caravaggio. The role of drawing in the genesis of Battistello’s works is clarified, thanks in part to the attribution of the drawings in the exhibition, which are kept at the National Museum in Stockholm, where they were brought in the late seventeenth century by the architect Nicodemus Tessin the Younger, returning from a trip to Naples. Of particular interest among the sketches is the one on the first Viceroy of Naples, used for the fresco in the Royal Palace, depicting the handing over of the keys to the city.

The itinerary opens with some video projections that send the viewer back to the atmosphere of 17th-century Naples. The exhibition layout, designed by COR arquitectos & Flavia Chiavaroli, is designed to enhance the similarities with Caravaggio, but also to study how Battistello deviated from it. The viewer, however, such is the extraordinary quality of the works on display, almost risks forgetting this play of references that the itinerary suggests. Other comparisons are suggested by the presence and juxtaposition of works by Francesco Curia, Jusepe de Ribera, and Mattia Preti. While the juxtapositions of these canvases are more canonical, if still interesting, the juxtapositions with the various sculptures, including that of a flagellated Christ compared to the works of Caracciolo, are of great effect. These juxtapositions cleverly suggest to us how painters and sculptors in the past had significant influences on each other’s works, in an atmosphere of often creative comparison.

On the occasion of the exhibition, some works have been restored and appear to us almost unseen. Particularly impressive is the 1627Immaculate Conception , from the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin in Roccadaspide (Salerno), an almost unknown work, also complicit in its poor state before restoration. Also striking is the Liberation of St. Peter from Prison, executed for an altar in the church of Pio Monte della Misericordia, where it is normally kept. The painting depicting the work of mercy of visiting prisoners already normally dialogues with Caravaggio’s Seven Works of Mercy in the same church: now, as a result of the restoration, Battistello’s painting looks striking and once again recalls Merisi with the character in the foreground from behind, but especially with the angel accompanying the saint out of the prison, whose face, shrouded in chiaroscuro more evident thanks to the restoration, represents a reference to Caravaggio’s characters. Displayed alongside this work is a helmet very similar to the one painted, an effective expedient that in turn also refers back to Caravaggio’s work, the Negation of St. Peter (too bad the comparison photograph on display is really small), where what would appear to be the same helmet used by Battistello in his painting appears.

It is worth noting positively how the explanatory captions of the works, perhaps still a bit small and often located in uncomfortable positions, are often full of interesting insights, effectively guiding even the average visitor with more specific notions.

The second location of the exhibition is at the Royal Palace in Piazza del Plebiscito. Here the viewer will be able to admire the so-called Sala del Gran Capitano, whose ceiling was frescoed by Battistello probably between 1610 and 1616 and which represents one of the few original 17th-century works in the palace, which was modified several times over the following years. The room can be admired in an unprecedented way, as the furnishings and the large chandelier have been removed; it also features new lighting that enhances the frescoes. The room was part of the apartments of the viceroy during the 17th century and later of Charles of Bourbon in the 18th century. The name of the room derives precisely from the ceiling frescoes depicting the stories of Grand Captain Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, who became the first Spanish viceroy of Naples thanks to two victories over the French army. While Caracciolo departs from his master by frescoing this ceiling, albeit with a naturalistic monumentality but lacking the classic Caravaggesque chiaroscuro, he also pays homage to the Lombard painter by including his very face behind the figures of the ambassadors offering the keys to the city to the Grand Captain.

The exhibition concludes with the third venue, the Carthusian Monastery of San Martino, where the tour proceeds through the church and the Prior’s Quarto gallery. Those who have previously visited the complex’s church will be enraptured by the new lighting, which again enhances the frescoes as never before. De Domenici stated that “...the most beautiful works of Giovan Battista can be seen in the beautiful church of San Martino...”: seeing them today with such different lighting than at the time may invite us to reflect on the original relationship of light to the works when they were created. At the same time, the choice of the Campania Regional Directorate of Museums to light the frescoes in such a modern way gives us the opportunity to read these works in an extremely clearer way.

In the Chapel of the Assumption, the cycle of frescoes traces the salient moments in the life of the Virgin Mary. The Chapel of San Gennaro sees, in addition to the frescoes by Caracciolo, interventions by Domenico Antonio Vaccaro and Cosimo Fanzago. Following the eruption of Vesuvius in 1631, the Carthusian fathers decided to entrust Battistello with a series of frescoes on the life of the saint to pay homage to his alleged intervention. The Chapel of St. Martin features the altarpiece St. Martin and Four Angels originally commissioned from Paolo Finoglio, but deemed unsatisfactory by the Carthusians. Battistello, who had already executed a work in the Chapter House and who made this canvas in about 1630, was therefore called in. In the Certosa Choir, which also houses works by Massimo Stanzione, Cavalier d’Arpino, and Guido Reni, Battistello had painted The Washing of the Feet in 1622, considered a great masterpiece by the artist, with its color contrasts and extreme chiaroscuro. The itinerary in the Carthusian Monastery dedicated to Caracciolo ends in the Prior’s picture gallery, where there is the Assumption, a work from 1631 that began as an altarpiece in the chapel of the same name, later replaced by a work by Francesco De Mura and then moved here, where four sketches of the frescoes in the Chapel of San Gennaro and some drawings are also on display today.

The author of this article: Francesco Carignani di Novoli

È esperto in management e politiche culturali.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.