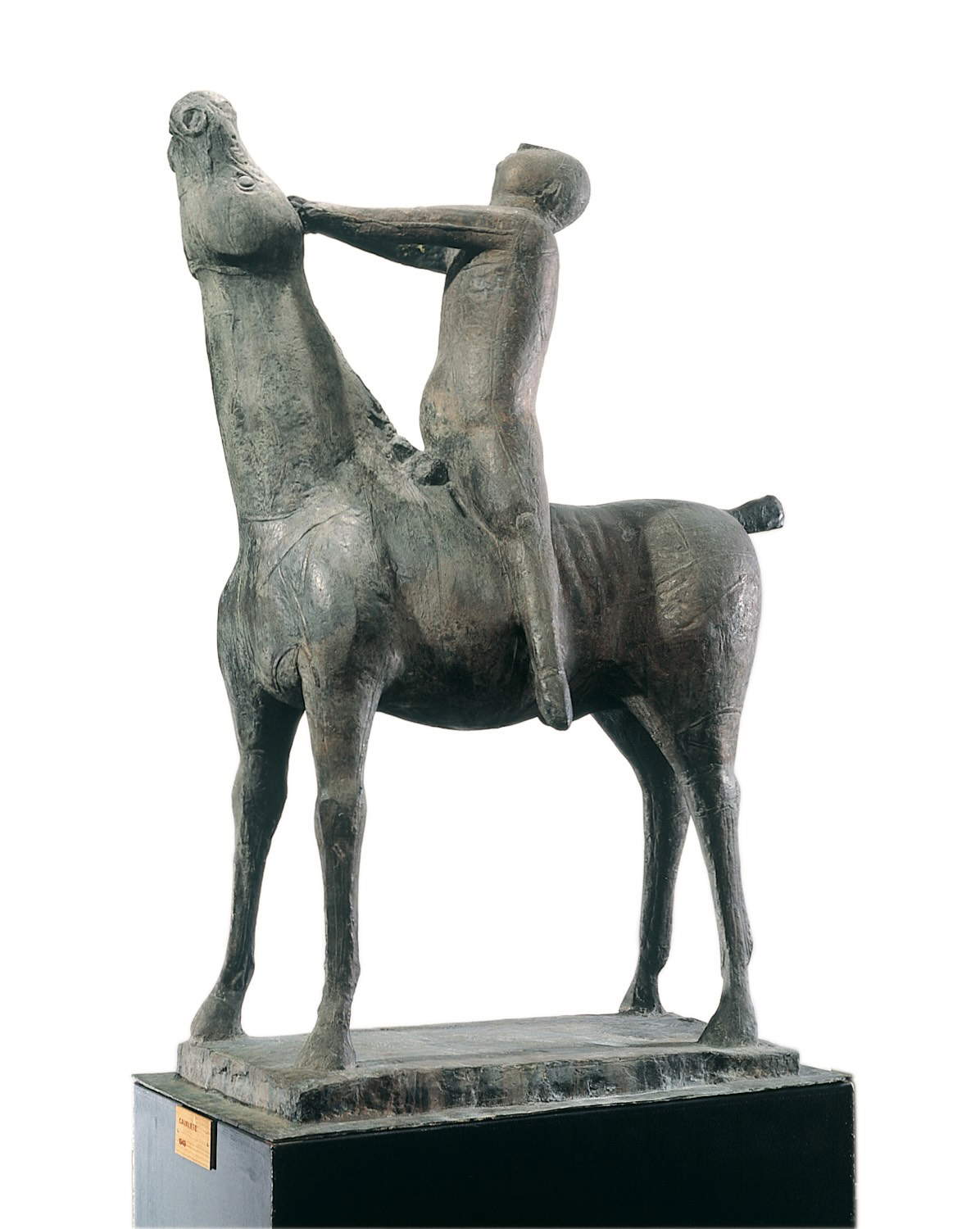

The name Marino Marini is associated with a well-defined subject with ancient origins: the rider riding his steed. Today we know that the domestication of the elegant equine took place some 5,500 years ago in Central Asia, and a very deep relationship between humans and horses has been established ever since. Docile and strong, tall and splendid, these animals for millennia have helped humans in field work, participated in battles, been used for transportation and for sport and entertainment, a role to which contemporary Western society has now relegated them. On a symbolic level, too, the horse-and-rider pair is firmly established, and its representation in the visual arts almost always evokes themes of heroism, triumph, and power: clear evidence of this is the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, Donatello’s Gattamelata, and Bernini’s Louis XIV , just to draw on different eras and styles. Marino Marini was already an established artist when, in 1934, he visited Bamberg and there he received the epiphany that marked the path of his production: he was in fact greatly impressed by the so-called Knight of Bamberg, a sculpture that stands out on a pillar of the cathedral choir and that dates before 1237, in the midst of the Gothic age in short. Unlike most of the better-known equestrian monuments, however, Marini’s horsemen have an anti-heroic connotation, which also distances them profoundly from the rhetorical triumphalism typical of the Fascist Ventennio, the era in which the first examples were made, and even the theme is on closer inspection far removed from the canons of his contemporaneity.

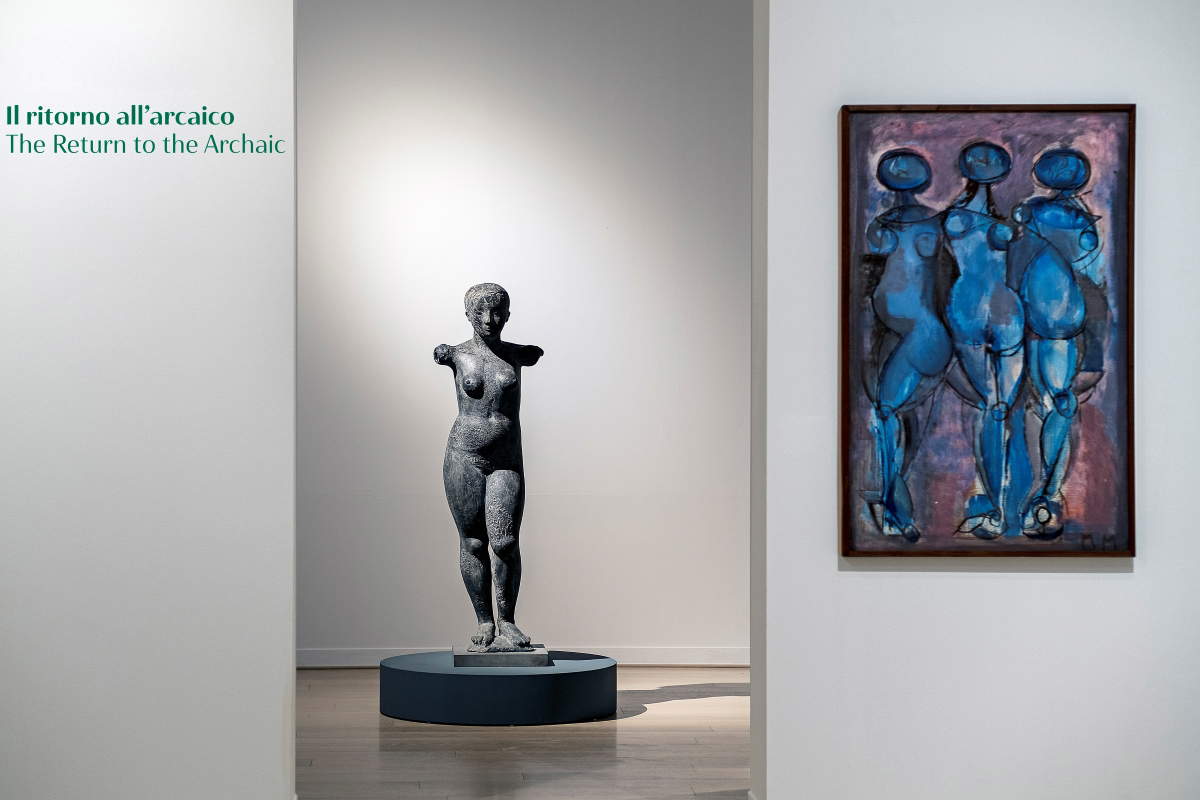

In Arezzo, after two significant exhibitions such as Afro. From Meditation on Piero della Francesca to the Informal and Vasari. Il teatro delle virtù, it has now been decided to pay homage to Marino Marini with an exhibition curated by Alberto Fiz and Moira Chiavarini and divided between the Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea and the Fortezza Medicea. The exhibition intends to bring to fruition a triangulation, albeit a temporary one, between the two most important conservation nuclei of Marini’s work, namely Pistoia (home of the Marino Marini Foundation) and Florence with its Marino Marini Museum, both institutions that have lent almost all of the works on display, some of which have been extracted from storage and therefore rarely seen by the public. Even the incipit of the exhibition itinerary speaks with a strong Tuscan accent: if the first work one encounters is theSelf-portrait of 1929, which is useful for visualizing the artist’s face, then stands out isolated Zuffa di cavalieri of 1927, a drawing from the Uffizi in which the battle scenes depicted by Piero della Francesca in the Bacci Chapel of the church of San Francesco, which moreover is adjacent to the exhibition venue, clearly resonate. Striking about this paper is the date of execution of the drawing, which was almost contemporary with the publication of Roberto Longhi’s first monograph on the painter from San Sepolcro. For Marini, moreover, the reference to Piero was essential from his beginnings, and this is also demonstrated by the painting The Virgins of 1916, which, in addition to certifying his precocious talent, expresses a reflection on the formal structuring of the 15th-century master.

The layout in the spaces of the Gallery is based on a thematic criterion, functional to understand the choice of Marini’s favorite subjects and to follow his stylistic changes, as well as the evolution that, starting from a classical construction, gradually transforms the figures, until touching on the poetics of the Informal. Speaking of roots going back to Antiquity, a small room displays some of the artist’s pieces (e.g. the plaster Torso of a Woman of 1929 and the Giovinetta of 1938, mutilated of the arms just like an archaeological find) that make manifest his inspiration from archaic and particularly Etruscan sculpture. To refute this, a display case collects a small terracotta head from Arezzo’s Archaeological Museum and a series of publications related to the Catona excavations conducted in Arezzo in the early decades of the twentieth century, likely known to Marino Marini. “I look to the Etruscans for the same reason that all modern art has turned back by skipping the immediate past and has gone to invigorate itself in the most genuine expression of a virgin and remote humanity. The coincidence is not only cultural; but we aspire to an elementarity of art,” the artist had to say. After all, the preclassical age is also looked at by the small bronze depicting a Boxer from 1935, and it is inevitable to think of the intense Boxer at Rest (4th century B.C.) in the National Roman Museum.

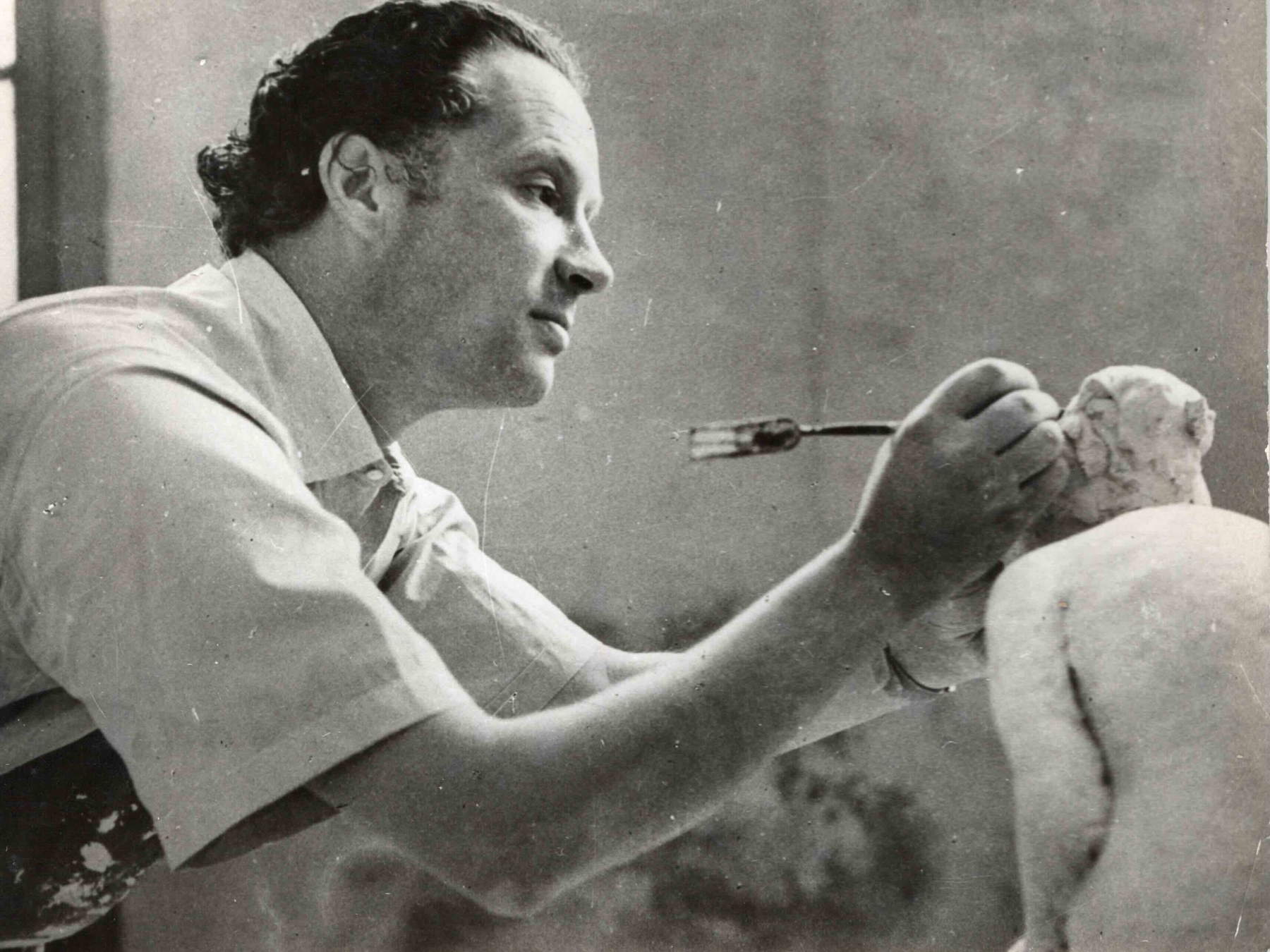

In the section devoted to the Pomones, one wanders around these mythological creatures that Marino Marini has actualized on twentieth-century stylistic motifs, while maintaining a strong classical setting; reliefs and paintings that multiply the femininity of the Pomones and decline it in the theme of the Three Graces or the Caryatids are also on display. Large sculptures are flanked by bronzes and, above all, painting, which for the artist has always been the premise of any creative result, as well as a means of studying the volumes of his figures: “It is color that always makes me begin. I always begin by painting [...]. You cannot isolate my sculpture, it is also an experience of color,” reports a panel with a quote from Marini himself. And that the symbiosis is unquestionable is proven by numerous effective juxtapositions throughout the visit.

This is certainly not the first time that sculpture and painting works by the Pistoiese artist have been combined in an exhibition: this was the case, for example, with the exhibitions Manzù/Marino. The Last Moderns (Magnani Rocca Foundation, 2014) and Marino Marini. Arcane fantasies (Aosta, Forte di Bard, 2024). However, in Arezzo, the paintings also rise to prominence thanks to the so-called “quadreria,” a high wall completely covered with paintings that can be admired both from below and from the second-floor balcony, which can be reached after encountering the core of acrobats and jugglers and dancers, figures that evoke humanity in the daily exercise of their craft and allow Marini to stop the moment that precedes movement.

The gallery just mentioned also houses a gem: the preparatory plaster cast of the famous horseman that still overlooks the Grand Canal from the terrace of the Guggenheim Collection in Venice. The work is recounted through the words of the sculptor’s wife: "In 1949 Peggy Guggenheim asked for a work on loan for the sculpture exhibition at Palazzo Venier in Venice. She was so impressed with the Horse and Rider with Arms Spread that she purchased it. When Marino saw it set so well in front of the Palace on the Lagoon he gave it the title The Angel of the City." His consort Mercedes Maria Pedrazzini (an idealized figure who was even renamed Marina by her husband to make her “part of himself,” as Alberto Fiz explains) is among the protagonists of the slew of portraits executed by Marini and in which the level of psychological research and emotional involvement prevail over the rendering of somatic features: in the exhibition the two effigies of Marina are followed by the heads of Fausto Melotti, Jean Arp, Igor Stravinsky, Massimo Campigli and others; then by Filippo De Pisis, who moreover was the first to dedicate a monograph to Marini. There is also the well-known portrait by Marc Chagall, who did not appreciate the work, seeing in it almost caricatural accents, and indeed warned the author against making it public.

On the second floor of the gallery, the focus is mainly on the Knights and their metamorphosis that broke down their forms based on post-Cubist matrices (the impact of Picasso’s Guernica is unquestionable) until they reached the apex of dissolution in the Screams. Alberto Fiz explains: "In the 1930s Marini’s Cavalieri are works of absolute balance, in which the horizontal element, the horse, dialogues perfectly with the vertical one, the man. Gradually, however, after the tragedy of World War II, this relationship is modified and strong tensions are created between the two elements, until the figurative image is overcome to arrive at the Miracles, the Warriors, the Compositions and the Screams, which constitute real cries of pain. It is a transformation with which Marino participates in the drama of man, and he does so by developing a path with elements that separate: the knight is unhorsed and the horse seems to point toward the sky, as he himself says.“ The curator, in this regard, also hints at a link between Marini’s poetics and the current of Spatialism: the sculptor, Fiz recounts, made explicit several times his intent to ”pierce the earth’s crust“ and ”even go into the stratosphere,“ in search of a profound connection between man and the cosmos. ”The Horseman is thus his most famous icon, which from equestrian monument becomes a fundamental factor of an increasingly fragile, increasingly problematic and perturbing contemporaneity." It is no coincidence that a 1953 Miracle was chosen as a war memorial for a square in Rotterdam, and in 1955 a large Composition was commissioned from Marini by the Municipality of The Hague as a colossal monument to the horrors of the conflict; on its base the sculptor engraved, “It was built, it was destroyed, and a desolate song remained over the world.”

In these sections of the Aretine exhibition, too, the relationship with painting is very close, and of particular note are the very balanced Gentleman on Horseback of 1938, The Troubadour of 1950 where the red of the horseman, with outstretched arms, charges the figures with energy as the head of the steed points upward, and then Warrior, an oil on canvas of 1960 that, if not contextualized, could certainly be interpreted as an excellent example of informal painting.

Finally, in the imposing Fortezza Medicea, an astonishing glimpse unravels thanks to a dozen monumental works that trace Marino Marini’s creative process, from a concrete Cavaliere, with its dusty, almost “soft,” to the reclining Pomona who, without her arms, stands precariously poised, to the androgynous Juggler of 1946, which to the writer seems to be an all-twentieth-century synthesis of Michelangelo’s Pietà Rondanini.

The Arezzo exhibition project bears as its subtitle “In Dialogue with Man,” and it is Fiz again who explains its meaning: “Contrary to an important part of contemporary art of the second half of the twentieth century, which has always been somewhat algid and cold with respect to basic needs, in Marino Marini’s work one perceives a high degree of empathy and a marked ability to touch emotions and feelings. It is also an existential work in comparison with the other great sculptor of the 20th century, Alberto Giacometti, but unlike the latter, who was linked to the alienation of the individual, Marini holds a different position, participatory, relational and never cynical. His suffering is never resignation; there is always hope, even in his last works.” It is an art, therefore, deeply human.

Strictly monographic, the exhibition is distinguished by the careful selection of works, about 120 in total, which offer a cross-section of Marino Marini’s poetics from the 1930s to the early 1970s, also illustrating the many techniques and different materials adopted by the artist: there are in fact sculptures in wood, plaster, ceramics and, as seen above, even concrete as well as, of course, bronze, sometimes polychrome. The layout is essential and accompanied by various educational panels that help visitors navigate their way through eras and themes. Also more than appreciable is the choice of placing the monumental sculptures in the Medici Fortress: the effect is so striking that it gives the impression that the works were made especially for those environments, and the light that falls from above highlights their theatricality or drama, as happens with the Miracles. It is a pity, however, that at the time of writing this article, there is still no trace of a catalog, a rather inexplicable absence considering that the exhibition, organized by the City of Arezzo and the Guido d’Arezzo Foundation, was designed by the cultural association Le Nuove Stanze and Mainz, a publishing house.

The author of this article: Marta Santacatterina

Marta Santacatterina (Schio, 1974, vive e lavora a Parma) ha conseguito nel 2007 il Dottorato di ricerca in Storia dell’Arte, con indirizzo medievale, all’Università di Parma. È iscritta all’Ordine dei giornalisti dal 2016 e attualmente collabora con diverse riviste specializzate in arte e cultura, privilegiando le epoche antica e moderna. Ha svolto e svolge ancora incarichi di coordinamento per diversi magazine e si occupa inoltre di approfondimenti e inchieste relativi alle tematiche del food e della sostenibilità.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.