It opened in Padua on Oct. 1 in the rooms of Palazzo Zabarella, and will remain open until Feb. 26, 2023, Futurism 1910-1915. The Birth of the Avant-Garde, one of the most anticipated and ambitious exhibitions of the season, curated by Fabio Benzi, Francesco Leone and Fernando Mazzocca. An exhibition that, according to the press releases on the eve and what is told in the panels at the entrance to the exhibition, aims to impose itself as “another look, offering a new and original vision and inviting the discovery of an artistic reality that until now has been little, or not at all, revealed.” In fact, according to what the curators state, although there have been multiple reviews dedicated to Futurism over the past forty years, “none has ever focused in critical and exhaustive terms on the cultural and figurative assumptions, the roots, the different souls and the many themes that contributed first to the birth and then to the deflagration and full configuration of this movement that so disruptively characterized the research of Western art in the first half of the twentieth century.” this is what the Padua exhibition aspires to. To this end, the exhibition can count on 121 works, creations by artists such as Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, Gino Severini, Fortunato Depero, Mario Sironi, Carlo Carrà and many others, linked with few exceptions to thechronological span 1910-1915, some of them rarely exhibited, from galleries, museums and international collections, for a total of more than 45 different lenders.

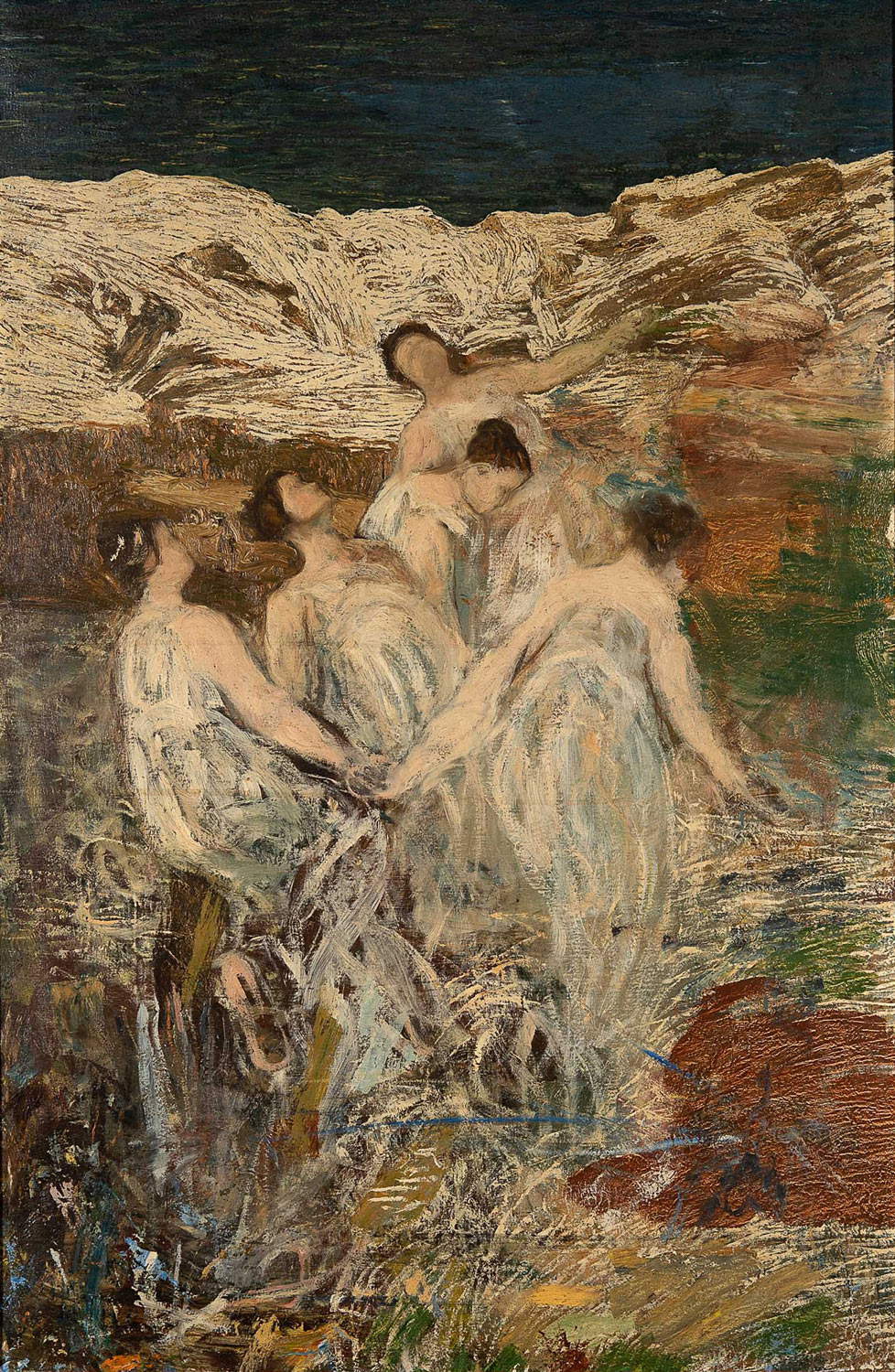

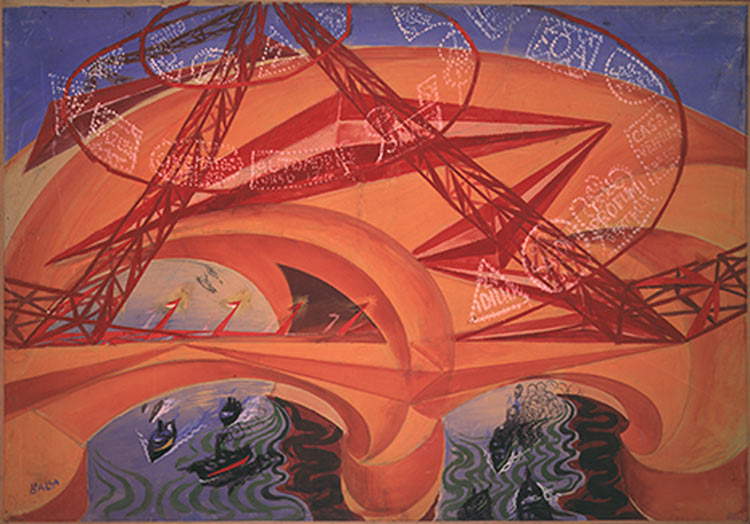

A challenge the curators meet by developing the exhibition by themes, only partly chronological, and rooms that, also through appreciable architectural and chromatic care, address the different matrices and natures of the early Futurist movement. The exhibition opens with two rooms that recount the Symbolist roots of Futurism and the links with Divisionist art (roots divided by curatorial choice), thanks to the comparison between the works of Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo among others, and those of the founding fathers of the movement, whose self-portraits are exhibited. A “dialogue” intended to attest to how these early Futurists “were united by an artistic formation of a secessionist nature, linked to Divisionist technique and the Symbolist temperament of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” Then follows a room about “Spiritualism” with a remarkable 1911 study of Boccioni’s States of Mind and other masterpieces by Balla and Luigi Russolo, among others. From room to room we reach the heart of the exhibition, which first features “Dynamism,” in which works by Boccioni, Balla, Severini, Sironi, Carrà, and Russolo face each other as well as those by Gino Rossi, Gino Galli, Ardengo Soffici, and Ottone Rosai.

Then “Simultaneity,” with works by Carrà, Boccioni, Fortunato Depero, Russolo and Enrico Prampolini. “Modern Life” characterizes the next passage, in a room intended to recount the revolutionary spirit and complete break with the canons of the past, with works by Sironi, Carrà, Boccioni, Antonio Sant’Elia, Depero, as well as Aroldo Bonzagni and Achille Funi. The themes of “Tridimensionality” in sculpture and “Polymaterism” are then investigated, where, as evidence of the use in art of different materials, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space and Development of a Bottle in Space by Boccioni, Balla’s Colored Plastic Complex of Line-forces (specially recreated for this exhibition since it was lost) and Depero’s Marionettes of Plastic Dances. After a section on “Parolibere,” the path winds up to the theme of “War,” seen by the Futurists as a means of getting rid of the old and boring past and letting youth prevail, a room characterized by masterpieces by Carrà, Balla, Sironi and Severini. Consistently, the “Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe” closes the itinerary, displaying works by Balla and “the concept of ’total art’ that takes possession of the world of men and things and that found precisely with the Futurists the first, full configuration within the avant-garde movements.”

This is in a nutshell the nature of the exhibition, set out in the words of those who put it together. And the signatures do not lie: there is on display a series of masterpieces, for the vast majority from extra-regional and some international loans, capable of giving the visitor a taste, a remarkable one, of the first five years of the Futurist movement, and also the chance to admire a hundred or so thick works, in succession, for an hour (or more) of artistic enjoyment.

The Padua exhibition, however, aims higher, on the strength of the package of works available, inviting, as mentioned, the visitor to discover and understand “the cultural and figurative assumptions, the roots, the different souls and the many themes that contributed first to the birth and then to the deflagration and full configuration” of the Futurist movement, aiming to move away from the usual exhibitions on Futurism. And it must be admitted that this goal, explicit and stated, is only partially achieved. If the selection of works is full-bodied and, albeit with the obvious limitations of a temporary exhibition, somehow able to offer a very broad, if not complete, overview of the years 1914-1915, those of the “full deflagration” of the movement at the turn of Italy’s entry into the war, the same cannot be said for the rooms concerning the origins and founding moments of the current. Which are the ones that, in the creators’ statements, provide the uniqueness of the exhibition. The connection with Symbolism, explained in the captions, is elusive in the selection of works on display, while the transition between pointillism and futurism lacks some key links: in the room that recounts it, along with works from 1909-1911, there is a decidedly more advanced and fully futurist Balla, dated 1918. While several points, names and events are taken for granted, some works, many to be sure, deserve more in-depth study, in order to involve in the “discovery” even the visitor who is avuncular to the dynamics and chronologies of the Italian avant-garde.

![Umberto Boccioni, Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio (1913 [1972]; bronzo, 117 x 30,5 x 87,5 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum) Umberto Boccioni, Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio (1913 [1972]; bronzo, 117 x 30,5 x 87,5 cm; Otterlo, Kröller-Müller Museum)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2022/fn/umberto-boccioni-forme-uniche-continuita-spazio.jpg)

Above all, Depero’s Marionettes for Plastic Dances, whose connection with the other works in the exhibition is barely hinted at. Perhaps too much has been exhibited, counting on attracting visitors on the basis of names and numbers: some of the works on display (few, it must be said, such as those by Gino Rossi, Arturo Martini, some from the pre-1910 phase) have more of a chronological-biographical relationship with the Futurist movement, unexplained and hardly intelligible to the visitor not preinformed about it. It seems no accident that most of these few “marginal” works in the exhibition are from museums and collections in Veneto. Perhaps there was instead a desire to explain too much, in too little space and with too many limitations, or perhaps it was a choice, because the result is a dynamism of the exhibition that seems to echo Futurist dynamism. But the consequence, certainly this one unintended, is that the visitor who enters to understand more about how, why, when, where Futurism was born, will come out confused or, at best, fideistically accepting what is displayed in the (precise and detailed) introductory panels in the rooms: for the individual works in fact, the captions are limited to author, title and date, leaving several questions open. Certainly with audioguides or, even more so, guided tours, these information gaps can be filled, but for an exhibition with an unassuming cost (15 euros) perhaps more insight could have been offered to the visitor even through the panels.

The visit, in any case, remains highly recommended. Both for those who know nothing, or little, about Futurism and the avant-garde, and for those who want to dive into a succession of rooms capable of offering unprecedented insights and sensations. Even more recommended for those who have no time, or way, to visit the great contemporary art museums of Milan, Rome or Florence, but also for everyone else. Only, one piece of advice seems to be in order: if you plan or suggest a visit to friends and relatives eager to understand more about the origins of Futurism, an audio guide, a guided tour or an informed companion could facilitate, and not a little, the enjoyment of the works and the understanding of the exhibition choices.

The author of this article: Leonardo Bison

Dottore di ricerca in archeologia all'Università di Bristol (Regno Unito), collabora con Il Fatto Quotidiano ed è attivista dell'associazione Mi Riconosci.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.