From October 23, 2025 to March 19, 2026, the Pinacoteca Comunale “Carlo Servolini” in Collesalvetti will host the exhibition Alberto Calza Bini painter and architect between Rome and Livorno. The Spirit of Classical Art, the Temptation of Art Nouveau, the Challenge of Divisionism, promoted and organized by the Municipality of Collesalvetti with the contribution of the Livorno Foundation and curated by Francesca Cagianelli. The exhibition opens on Thursday, Oct. 23 at 5 p.m. in the spaces of the Villa Carmignani Complex, home of the Pinacoteca, and can be visited free of charge every Thursday, Saturday and Sunday from 3:30 to 6:30 p.m., as well as by reservation for small groups, with the possibility of free guided tours. The project is chaired by a scientific committee composed of Francesca Cagianelli, curator of the Pinacoteca; Alberto, Alessandro and Paolo Calza Bini, heirs and scholars of the artist; Dario Matteoni, former director of the National Museums of Pisa; Alessandro Merlo, lecturer at the University of Florence; Flavia Matitti, lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome; Simone Quilici, director of the Colosseum Archaeological Park; and Vieri Quilici, architect and professor of Architectural Composition.

The exhibition constitutes the first extensive study of the pictorial and graphic production of Alberto Calza Bini (Rome, 1881 - 1957), a figure best known as an architect and urban planner, celebrated by historiography thanks to studies by Giorgio Ciucci, Cesare De Seta, Italo Insolera, Fabio Mangone, Paolo Nicoloso and Bruno Zevi. Now the Servolini Art Gallery also restores him as a painter and engraver, documenting his artistic career from his beginnings at the Regio Istituto in Rome, between 1895 and 1900, to 1916, the year of his participation in the Exposition of the Italian Association of Acquafortists and Engravers in London and the Self-Portrait Exhibition of the Artistic Family in Milan.

The exhibition reconstructs the dimension of an artist capable of traversing the major Italian and European exhibitions of the time. Calza took part in the Società Amatori e Cultori di Belle Arti in Rome, the Promotrice in Genoa, Turin and Florence, the Bagni Pancaldi Exhibition in Livorno, the Roman Secession, the Permanente and the Famiglia Artistica in Milan, and the Italian Engraving Exhibition for the Red Cross in London. Among his earliest successes is Anima vesperale, presented in Rome in 1904 and now exhibited again in Collesalvetti. In this work the artist’s sensitivity to the landscapes of Calvi dell’Umbria, a place to which he remained attached throughout his life, emerges. In 1906 Calza Bini moved to Livorno as a teacher at the Technical Institute and, alongside his wife Irene Gilli, also a painter and engraver, came into contact with the environment of the Caffè Bardi and with intellectuals and artists such as Lorenzo Cecchi and Pietro Vigo. Gastone Razzaguta ironically called him “the etcher on the move.”

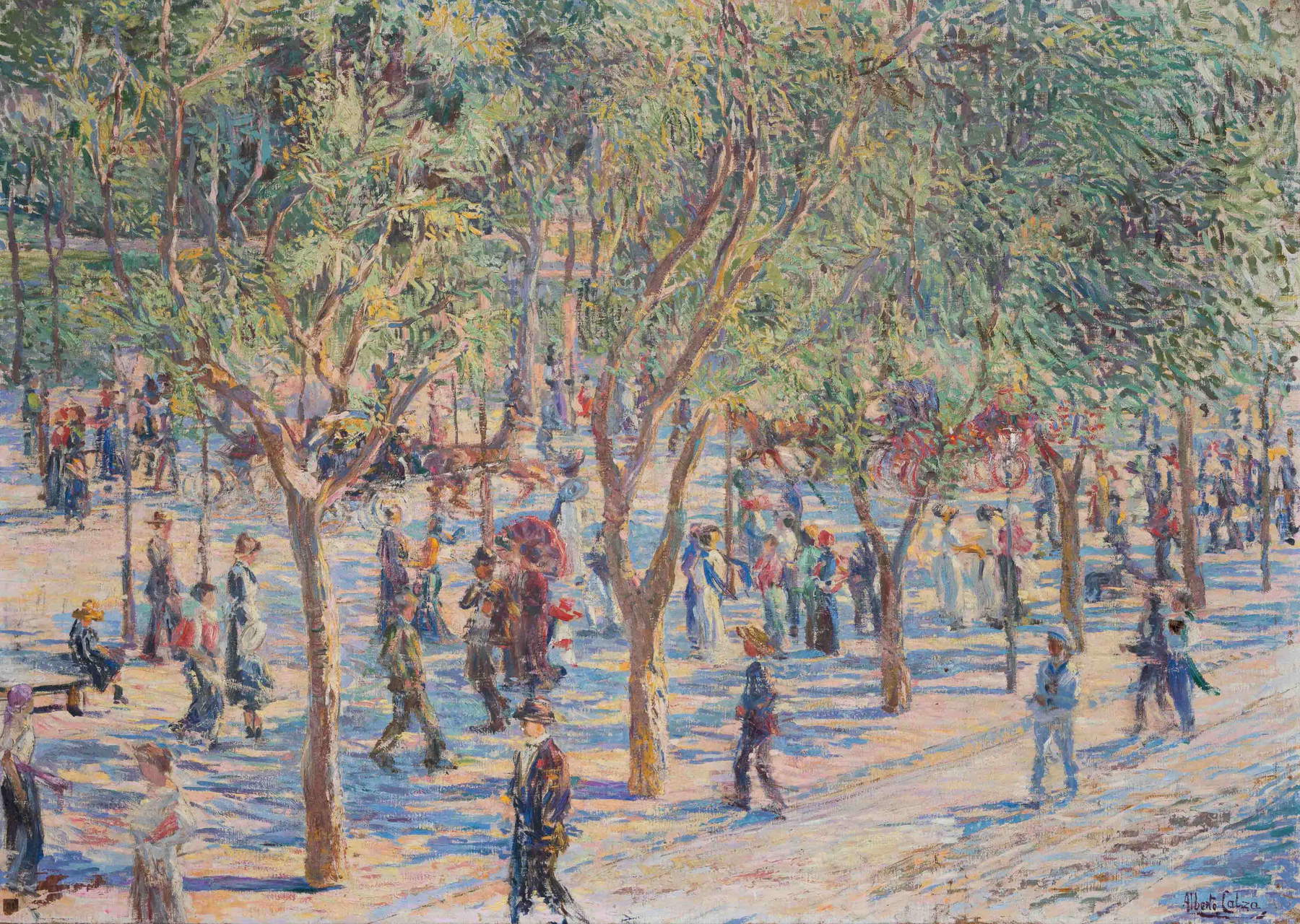

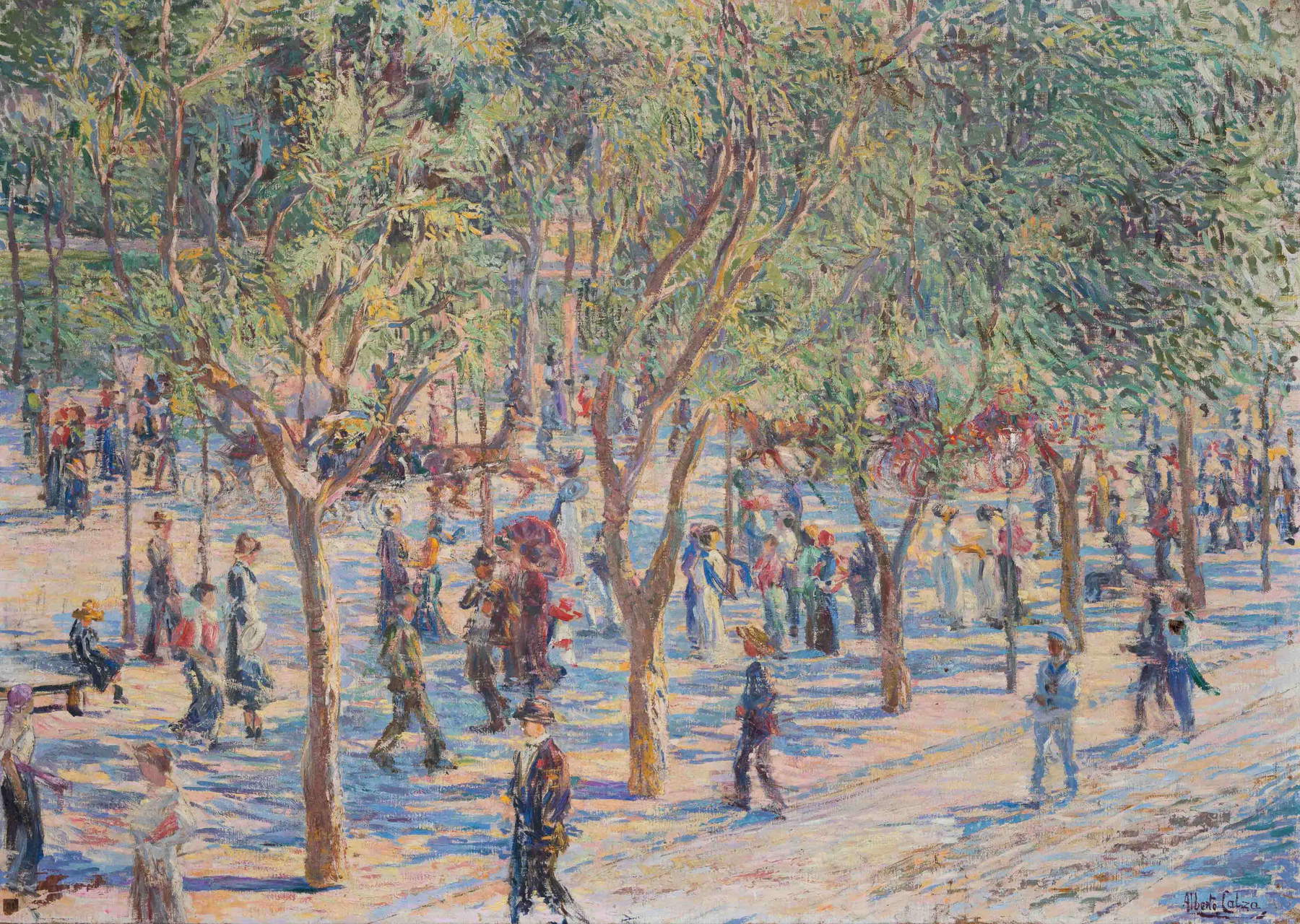

His gaze then turned to the port city and its landscape, resulting in luminous, Divisionist views. In 1908, the year of Giovanni Fattori’s death, Calza signed Il Fosso Reale, a masterpiece chosen as the exhibition’s icon, in which the heart of 19th-century Livorno is transformed into a scene vibrant with light and crowds. In addition to this, the Pinacoteca presents about seventy previously unpublished works from the Calza Bini Collection: paintings, drawings and engravings that tell the story of Livorno’s port, pine forests, gardens and nocturnes, with a language that interweaves realism and luminous abstraction.

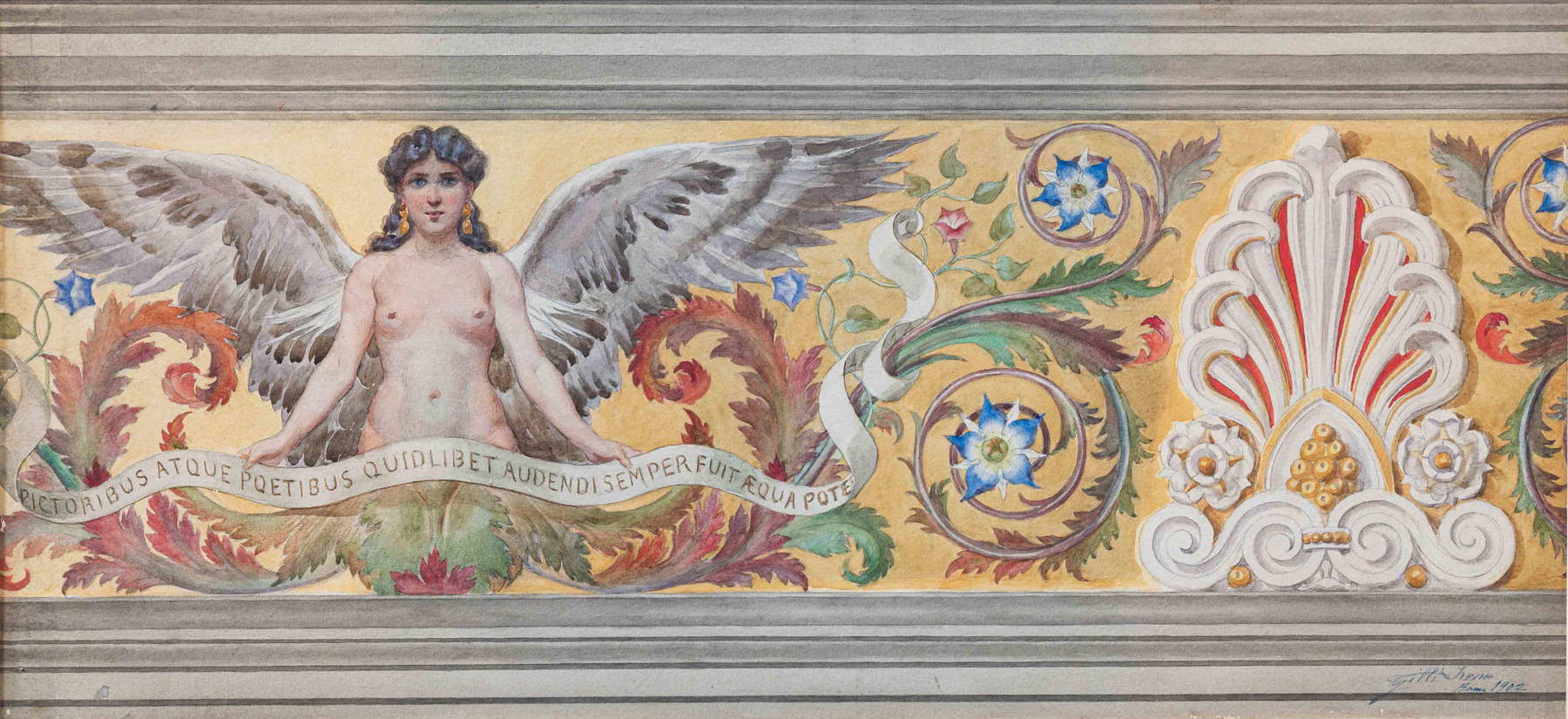

An important chapter is devoted to the link with Plinio Nomellini, with whom Calza formed a long-standing association, as much on the occasion of the setting up of the Sale Livornesi of the Tuscan Pavilion at the Regional and Ethnographic Exhibition at the 1911 International Exhibition in Rome, as at the junctures of the Competition for the Lunettes at the Vittoriano and then at theInternational Art Exhibition of the “Secession” in Rome in 1913, the latter episodes testifying to Calza’s unprecedented role, not only as a skillful institutional and artistic director and coordinator, but also as an attentive and up-to-date intellectual grappling as much with the mysteries of ancient art as with the challenges of contemporaneity.

Also presented in the exhibition will be the exceptional discovery, which occurred during the scientific committee’s investigations, of an unpublished letter by Calza on the letterhead of the Commission for the Conservation of Monuments of the Province of Livorno, addressed to the Royal Superintendent of Monuments for the Provinces of Pisa, Lucca-Livorno, postmarked July 21, 1912, which offers the key to adequately and definitively rereading the complex personality of the Roman artist, fascinated by the Gothic atmosphere of theHermitage of the Sambuca in Collesalvetti, a monument with which he had the opportunity to measure himself, but at the same time aware of the need to colloquy with the outposts of artistic innovation, exemplified, in this specific case, by the stained-glass window of the vestibule commissioned at the Fornaci di San Lorenzo. This episode testifies to another association, that with Galileo Chini, which continued until the threshold of the second decade, as attested by the unprecedented stained-glass windows signed, commissioned by Calza himself, for the housing complex for the “Cooperative Leonardo” in Rome.

The exhibition is divided into four sections. The first, entitled The musicality of light, the impetus of movement, the dream of the soul: Alberto Calza Bini’s Vesperal Soul between Calvi dell’Umbria and Livorno, opens with the tormented Self-portrait, dated November 29, 1901, programmatically set on academic arrangements, but already vibrant with dramatically fractured drafts that anticipate the masterpiece, theAnima vesperale of 1903, marked by a pervasive empathy with respect to the beloved landscapes of Calvi dell’Umbria, and presented at the 1904 LXXIV Esposizione Internazionale di Belle Arti della Società Amatori e Cultori di Belle Arti in Rome. Then exhibited is Il Fosso Reale di Livorno (The Royal Ditch of Leghorn), which precurses the events of Labronian pointillism with one of the most spectacular views of the city of Leghorn. The section also features Calza’s earliest etchings, from Il giardino delle Orsoline di Calvi (c. 1906) to Il Porto di Livorno (1907), a cornerstone of the celebration of the port scene initiated to coincide with his’landing in Livorno as a drawing teacher at the Livorno Technical Institute, not to mention Il pesco, a work presented at the 1908 Turin Quadriennale, titled in plate with lines taken from Giovanni Pascoli’s poem of the same name, included in the 1891 Myricae: “Among their trunks that no one ever sees, / beyond the steep wall and the doors /which have forgotten the hinges, one believes/ Death is dead.” Concluding the visual itinerary organized by Calza in the most characteristic meanderings of the maritime department are some daring nocturnes such as Il Fanale: Nocturne with Boats in the Port of Leghorn (1908-1909), where the contamination between the inquisitive curiosity addressed by the Roman artist to the historical monuments celebrated by the erudite Pietro Vigo and the epic transfiguration of the Tyrrhenian Sea, whose luminous and chromatic splendor will be at the origin of a constant pictorial reflection destined to result shortly thereafter in a kind of musical abstraction, is implemented.

The second section, entitled Divisionisms and Secession: Alberto Calza Bini and the New Pictorial Perception of Dynamism, illustrates that increasingly passionate expressive battle for the restitution of natural scenery vibrant with landscape melodies that were capable of restoring not only “the dream of the soul, but also ”the musicality of light," hinged between two episodes of identical setting but complementary technique, such as the two versions of Pineta di Livorno (1906-1908), both of which pay homage to the tourist itineraries of the Leghorn area extolled in monographs illustrated by the ’erudite Pietro Vigo, and the Passeggiata all’Ardenza (1910-1913), where the earlier Divisionist inclination seems to compact itself into broader drafts of fauve assonance, only seemingly competing with certain scenarios by Armando Spadini, but if anything closer to the chromatic flaking conceived in an almost coeval period by Ludovico Tommasi. Standing out among the unpublished works in this section isSelf-Portrait (1910-1911), presented at the 1916 Self-Portrait Exhibition at the Famiglia Artistica in Milan, responding, like so many others, as Vittorio Pica enunciated in his introduction to the catalog, to the need to revive the glories of portrait painting with respect to the landscape vein. Against Vittore Grubicy’s pressing invective against a pictorial genre inevitably contaminated by literary temptations, the critic in fact claimed the aesthetic dignity of the self-portrait: “Vain desire? And why not rather naive and untamable manifestation of that instinctive need, common to every class of men, to rebel against the ruthless destiny that confines their appetites and aspirations, thoughts and actions, joys and sorrows in a more or less short turn of years?” The section concludes in the sign of an embrace with Nomellini, with experiments such as the diptych composed of Marina and Onda, both attributable between 1910 and 1913, where the stylistic determination toward that “impetus of dynamism” placed at the apex of Calza’s reflection as an alternative to the prevailing Futurism is shown more tightly.

It continues with the third section, entitled La divina impronta della Bellezza: il sodalizio tra Alberto Calza e Irene Gilli al tempo del Regio Istituto di Belle Arti di Roma, which summarizes the outcomes of the academic apprenticeship conducted by the Roman artist and his future consort Irene, respectively under the aegis of Francesco Prosperi and Domenico Bruschi: their refinement of Nazarene ascendancy is due to that temper of renewal that saw precisely within the Scuola di Figura Disegnata the replacement of Morghen’s prints with “photographic reproductions of the best drawings executed by the Great Masters of the 15th century and the first half of the 16th century,” as well as the ’landing at an address of “drawing from relief” that privileged “artistic drawing,” that is, “which must express all the modifications produced in the relief by light,” and was based on the study of “casts of portraits of the most effective and beautiful Roman sculpture and the best Greek statuary.” In the academic compositions exhibited here for the first time, from church interiors signed by Calza to end with the Art Nouveau anticipations of Irene Gilli, such as Studio di grottesca, Roma (1901), or even certain of her neo-Gothic digressions such as Porta Medioevale. Studio di composizione (1901-1902), one will have to extrapolate against the light both the beginnings of Alberto’s future decorative and architectural vocation and the most authentic motivations of his wife’s aesthetic orientation, who, between Purism, Pre-Raphaelism and Art Nouveau, skillfully modulates the register of her pictorial and graphic production, without ever forgetting the lesson of her father Alberto Maso Gilli.

Finally, the fourth section, entitled Irene Gilli, painter and etcher between Pre-Raphaelism and Art Nouveau, constitutes the very first exhaustive lunge into the unknown, yet fascinating and significant, personality of Irene Gilli (Turin, 1884 - Rome, 1962), wife of Alberto Calza, a painter and etcher who imposed herself on the Italian exhibition scene in the first two decades of the twentieth century, but relegated so far to a cone of shadow, yet a protagonist in the Giolitti era. Fresh from her apprenticeship at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, Irene participated in major Italian and international exhibitions for about fifteen years. Daughter of Alberto Maso Gilli (Chieri, 1840 - Calvi dell’Umbria, 1894), considered among the greatest engravers of the time (not coincidentally appointed Director of the Royal Chalcography of Rome in 1885) Irene boasts as her greatest historiographical source the entry first dedicated to her by Luigi Servolini in his Illustrated Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Italian Engravers. The nucleus of unpublished works, returned for the first time to the public of the Pinacoteca Comunale Carlo Servolini, constitutes a unique opportunity to savor the artist’s variegated personality, indebted to the sumptuous eclecticism of the 19th century and, at the same time, informed by the purist temperament and Pre-Raphaelite taste, not without neglecting the stylistic features of Art Nouveau. The exhibition itinerary winds its way through pictorial works such as The Immaculate Con ception (1900-1905), a devotional silhouette stretched out toward the blue sky, and the Madonna (copy from Raphael), a valuable attestation of the Nazarene and Purist temperament, perhaps directly inspired, according to what is speculated in the catalog, by Sassoferrato’s Madonna and Child, preserved at the Galleria Borghese. There are also examples of Irene’s etching production, such as Alba claustrale nel giardino delle Orsoline di Calvi (1906), Il Pozzo alle Pianacce, Livorno (1906), and Le Tre Marie (1907). Irene Gilli was moreover enthusiastically hailed by Raffaelle Calzini at the 1916 London Exhibition: “She is among the Italian artists one of the few who devote themselves to painting and engraving with seriousness of purpose and with personality.”

The catalog, published by Silvana Editoriale, delves into the themes of the exhibition with essays by Francesca Cagianelli, Dario Matteoni, Alessandro Merlo and Flavia Matitti, who respectively analyze Calza Bini’s pictorial and engraving career, her relationship with Art Nouveau in Livorno, her role in defining the identity of Italian architecture between the two wars and the rediscovery of Irene Gilli.

The exhibition is flanked by the cultural calendar Livorno and the Tuscan Pavilion at the Rome International Exhibition for the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Unification of Italy. The Calza Case Between Art Nouveau, Divisionism and Secession, conceived by Francesca Cagianelli and promoted by the Municipality of Collesalvetti, which broadens the reflection on Calza Bini’s artistic and architectural season.

|

| Collesalvetti, an exhibition to rediscover Alberto Calza Bini, early 20th century architect and painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.