Edoardo Tresoldi (Cambiago, 1987), the artist of “Absent Matter” and wire mesh cathedrals, named by Forbes in 2017 among the most influential artists under 30 inEurope, talks about himself in a face-to-face dialogue with Giorgia Salerno, the curator who selected his work “Sacral” for the MAR - Art Museum of the City of Ravenna, the first public museum to acquire one of his works.

GS. In 2019 I contacted you to take part in the Dante exhibition Un’Epopea Pop realized at MAR - Museo d’Arte della città di Ravenna on the occasion of the 7th centenary of Dante Alighieri’s death and for which I curated the contemporary art section. The curatorial project, born in an experimental form by attributing to the selected artworks a Dantean identity and thus creating a close and dialogue between literature and art, you liked it and we chose Sacral, made in 2016 and reinstalled in the sixteenth-century cloister of the museum. An architecture reminiscent of those of Bramante and Michelangelo, an imaginative work that for me well represented ideally the “Castle of the Magni Spirits,” an emblematic place that Dante inserts in the 4th canto of theInferno, inhabited by philosophers and poets, the Magni spirits of antiquity who in life were men worthy of praise but destined for hellish suffering because they lacked the theological virtues. How did you find yourself in this capacity as an interpreter of Dante that I wanted to attribute to you?

ET. From the very beginning the project struck me very much thinking that I was distant from the world of Dante that I would somehow have to interpret with Sacral, but you had the ability to track down a fitting and particularly suitable reading with respect to Dante’s Noble Castle. Although Sacral was not initially conceived for this place a natural dialogue was created that I could hardly have designed more effectively. Sacral has been exhibited in China, in Rome... Yet here it has found its ideal space. It is “an anti-architecture” carved inside a decomposed cubic block that carries classical elements. It is a relic of a series of elements that are part of a cultural structure common to all of us, and it is something that relates back to a panorama of ours, and that is why it seems to have been born to be there. It is one of the works that I am most attached to and I am happy with this dialogue with Dante that is so harmonious created in the contamination of spaces and worlds that are so distant and so close together.

Let’s take a step back and talk about your debut before becoming the artist of “Absent Matter” and wire mesh cathedrals. Your artistic career began very early after studying set design in Rome, and in 2013 you made your first major work in Calabria, “The Collector of Winds,” a man looking at the sea. You were born in Cambiago, how come you chose the sea as the first landscape to work on?

When I started working with wire mesh, the landscape entered fully into the figures and gave them either a note of serenity or disturbance depending on the type of light present; at sunset or during a thunderstorm for example, and I realized that the work I was carrying out on transparency was not just something instinctive that I perceived as necessary for me, but it was a way of absorbing the landscape and canceling the abstract separation that exists between us and what we have in front of us. The sculptures I made at the beginning of my journey inserted an additional filter, between the people and the landscape, and I was looking for a key to interpret the sea... I was born and raised in the plains and the sea I came to know very late but the plains gave me what somehow the sea gives me today. We live in big cities but there are times when we look for emptiness: it is man’s own need to enter inside the landscape and to make the landscape enter inside us. This is what I do with my work. There is an external landscape and an internal landscape, and there are elements that dialogue between what is outside and what we have inside. It is something we all do on a daily basis with simplicity by experiencing places and people. The collector of winds is nothing more than a human figure capable of establishing a relationship with all those who live that place, even if only for a walk, because this is what we all do: empathically establishing a relationship with places through specific elements.

You talked about the emptiness that humans need and that we all, in some way, also seek through the landscape. In your twenties you moved to Rome, a complex and visually rich city of ’fullness’ architecturally; a city in which to find emptiness and silence it is necessary to seek shelter in churches, sacred islands in majestic and powerful buildings. How effectively have Rome, its history and domes, Michelangelo and Bernini influenced your work as a sculptor, set designer and artist?

My work is based on building a relationship through codes, and through what I read and interpret of the landscape, and at the same time, everything I create is a series of archetypes that I have absorbed during my journey. The sensibility with which I read and define my projects comes from a more intimate, personal, and childlike experience of my landscapes that pass through the period of my studies in set design and especially pass through this great overpowering filter that has been the city of Rome. Before arriving in Rome I lived in a small town of eight thousand inhabitants and in moving to such a chaotic and heterogeneous city undoubtedly I was overwhelmed by a series of elements and inputs that surrounded me and allowed the construction of a library of codes that perhaps we all have inside. I try to work through architecture and on linguistic codes that are recognizable to everyone in a simple way; these are the archetypes of architecture. I don’t choose complex figures, and when I use a colonnade, a dome or a church to tell something I am sure that, especially in Europe and Italy, most people have already built a relationship with that kind of element. When I began to work more consciously on space I felt the need to use those elements that Rome itself had made me absorb. The church, as you also stated, is a kind of bubble that manages to build an intimacy and it is the same with my works. Over time I realized that my work had to deal mainly with public art, with works to be made in shared public spaces where a collective ritual is experienced. The most interesting experience and one that I think is really ’sacred’ is being able to build places where people can share a moment of intimacy and solitude, the more you can build this relationship the stronger the perceived sacredness will be, and in a church exactly the same thing happens. I don’t know the exact reason why I started to think about the concept of emptiness but I felt the need to work with something that did not impose itself in space and so I realized that that something was precisely the absence of things. From that moment I began to develop more specifically this path of investigation. The personal landscape that we experience is made up of absent presences that can either be shortcomings that we have experienced or mental projections, a series of elements that we use to filter what we see and experience because our landscape is not made up only of pure and true elements and art tries to work on the immaterial.

For the past few years you have formed the interdisciplinary research group STUDIO STUDIO, which is involved in promoting other artists and developing new projects, again in the field of public art. How do you choose the work of other artists and what kind of projects do you favor?

Over time I have come to realize that public art is a specific practice, a discipline that puts at the center of the workbench the public space that is composed of a series of readings and elements that are part of the communities that experience places. When you make a work in a city, it becomes part of the city itself and a direct relationship is built between the work and the people who inhabit that place and who are therefore entitled to express an opinion or interact with it. It is necessary, therefore, to begin a reasoning precisely with communities by establishing a dialogue that is built over time. We can identify different types of landscapes related to a place: the natural, social, cultural, historical or even the legal landscape. Moving elements among these landscapes is like the brushstroke on a canvas with which the work is constructed. From these reflections STUDIO STUDIO was born with the idea of pursuing projects that specifically deal with public art. Making public art requires a larger structure than an artist can use, in the more traditional use of the term. “Making landscape” requires not only specific materials and tools, such as bulldozers, but also a range of different professional skills. In the case of large works created in public spaces there are many figures involved, from the most abstract idea of the project to the most technical aspects, and all these elements, as well as the actors involved, are part of the constitution of the work of art.

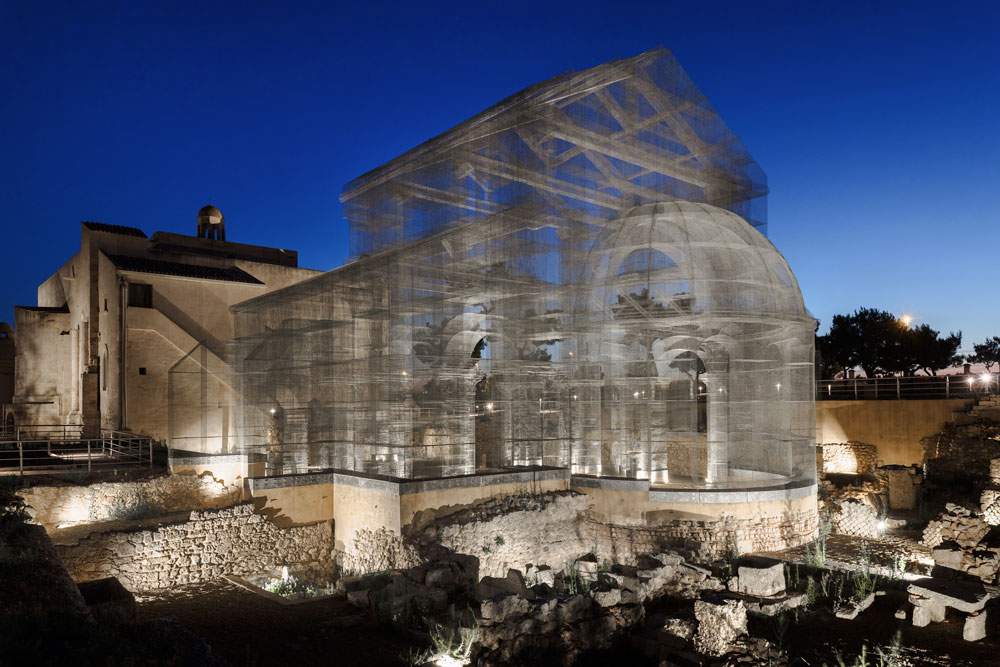

To “make landscape,” therefore, you need a wide network of collaboration and in-depth knowledge of the territory and the community with which you establish a relationship. In 2016 in the Archaeological Park of Siponto you experimented with one of the most difficult artistic dialogues to establish, that between contemporary art and archaeology, building a structure that evokes the no longer existing Paleochristian Basilica but without faithfully reconstructing it. This is one of the most extreme relationships between two seemingly distant worlds. Your Basilica was also awarded the Gold Medal for Italian Architecture. How did you approach this work that certainly involved several technical studies and also the responsibility of intervening in the history of that territory and its genius loci?

Continuing my research, I developed a system that allowed me to use wire mesh in the large dimensions, without having to insert solid elements that would have broken the expressive force of the transparency. Siponto enshrines an important moment in my journey, tracing the possibility of intervening with my gaze as a contemporary art artist directly on historical heritage. However, the goal was not to tell the past through contemporary art because it is the past that has given contemporary art the opportunity to express itself. It was a project that was particularly praised by critics and the world of archaeology, contemporary art and architecture because there was the possibility of reconstructing the Basilica with an innovative language without creating a false history and experimenting with contamination between different disciplines.

Among the landscapes you mentioned there is a particularly complex one that includes different aspects of the process of making the work, from organizational and logistical to conservation. This is the legal landscape that is composed of different requirements and also of many technical figures. One issue that is part of this specific landscape is the maintenance and restoration of works. What are your thoughts on the protection of your installations and what value do you place on the mark of time on them?

This for me is a theme that is very dear and central to my artistic journey. I make public art works that are created in open environments and are subject to weather phenomena and, therefore, their transformation. When I worked in Siponto, most of the questions were precisely about the ’durability’ of the work. There are artists who choose to make ephemeral works built with natural elements or destined to decay, this is the experience inherited from land art. Although wire mesh is certainly more durable it is clear that my installations will fall sooner or later. Siponto will fall sooner or later, it is impossible to deny that but to deny an artwork the possibility of ’dying’ is also to deny it the possibility of expressing itself as a living being. I had to confront this reality precisely when designing the Basilica of Siponto, and I wondered how I could make it with stronger materials. It was like dealing with a living being that transforms over time and ages. The monument is a rhetorical figure that is part of our cultural civilization that was originally created as a historical testimony, but human thought changes and the values of our societies change as well, which is why it happens today that we do not ethically agree with the human profile of a subject portrayed in a sculpture or monument. Our society is evolving with great speed, and human thinking in 20 years will be completely different from what it is today, just think today of the distance between digital natives and people born in the 1960s, and the cultural distance of these worlds creates strong contrasts. The twentieth century was the century of acceleration, and we are now experiencing the second phase of this process. Therefore, the monument has changed its value, and today it might appear as pretentious to future generations. Monuments celebrate the values of a society at the very moment when we are still defining them and with the risk, therefore, of rapid change. But the celebration of values is an action proper to contemporaneity that can be limited to the present without the need to leave a testimony to posterity. Only then in ten, twenty and thirty years will we be free to modify that presence with the knowledge that its existence does not represent an immutable cultural legacy.

Your sculptures, then, possess their own life cycle, they are born as impalpable and majestic figures that converse with the landscape and, in the distant future, at the end of their existence, they might merge with it altogether and then be reborn through the thought and gaze of other visionaries, artists or architects, as indeed history teaches us... For works designed for temporary projects, not lasting like Siponto, but still requiring a long planning, do you have a different thought and approach?

There are works of art that can have an end and, after years of existence, can leave a void or evolve and transform into something else. History is made up of layers of identity and it is possible to assume additional interventions on works, on architectures that no longer exist, but what is important for me is that the temporal difference is very evident because each layer represents its time. That for me is making landscape. The works that have a shorter duration still establish a relationship with the territory by entering the everyday life of people, allowing to create with the public landscape moments of intimacy. In some places I prefer to install temporary works that still have an average duration, such as can be five years, the right time for a child to be able to get used to an architecture in its territory, build its own visual landscape and afterwards recognize its emptiness. That emptiness will be the tow for the child to imagine new perspectives, to make room for the construction of new ideas. The relationship established with the works, even in the short term, allows the creation of a presence and, later, to develop an awareness of its absence, giving it greater value.

With reference to public art interventions and precisely to the absence and emptiness created by the “end” of a work, I ask you what you think of Giuliano Mauri’s Vegetable Cathedral, the second Cathedral rebuilt in Lodi to Mauri’s design after his death and recently destroyed. Do you agree with its eventual reconstruction?

In general I don’t agree with the idea of rebuilding this kind of project. I certainly believe in the opportunity to create something new, but faithfully reconstructing architecture that has been destroyed represents for me a failure to transform the present.

At Arte Sella, a nature park in Borgo Valsugana that is home to several contemporary art sculptures, you have created Symbiosis, a work that is different from your other architectures, which, while always maintaining the distinctive and identifying features of your work, is characterized by a strong material component: stone. Looking at this work and your other projects, I ask you how your artistic path has changed, how you still believe it will evolve in the future, and if there is an unrealized or unrealizable project, even a crazy one, that you would like to experiment with.

I started nine years ago to tell the story of transparency, a main element in my research path that continues with an increasingly careful linguistic investigation of the landscape. Now I am analyzing a number of themes and considering their feasibility, I am also thinking about the virtual. Speaking of impossible projects, I would also like to work on the ridge of a volcano...imagining a work that melts with lava. I have also been thinking for a long time that I would like to work on the territory where I was born, that of the Milanese hinterland, and since June 2022 I have started a landscape research project in an agricultural field in Carnate where I have installed a sculpture made in 2016 and whose process of absorption by nature will be observed in the years to come.

Today, thanks to the administration of the Municipality of Ravenna and the valuable contribution of the Marcegaglia Group, the work chosen for the Dante exhibition, Sacral, becomes part of the collections of the MAR - Art Museum of the City of Ravenna, the first public institution in Italy to acquire one of your works. I am very happy to have chosen you for this project and this acquisition that enriches the contemporary art heritage of the museum. Sacral in a short time has become an iconic and identifiable work of the MAR and that today becomes part of the cultural stratification of this place by referring to an evoked imaginary that reconnects history, narrative and contemporaneity.

One year after Sacral ’s installation, I am happy that it will become part of the museum’s permanent collection, especially since it is the first museum to acquire one of my works, and here it will be able to continue its relationship with the place.

The author of this article: Giorgia Salerno

Storica dell'arte e curatrice. Attualmente è conservatrice del MAR - Museo d'Arte della città di Ravenna. Formatasi tra Palermo e Roma, ha lavorato nel settore dell'organizzazione di mostre e come registrar per la Galleria Lorcan O'Neill.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.