It was due to the foresight of the authorities of the Venetian Republic that what are now the Musei Civici agli Eremitani in Padua, one of the oldest museum complexes in Italy, came into being as a result of a specific event dating back to 1784. The year before, in fact, the republic had obtained a brief of suppression for the houses of the order of the Lateran regular canons, which in Padua were based in the church of San Giovanni di Verdara. To “prevent the squandering of books and art objects” (so wrote historian Giuseppe Valentinelli as early as 1872), the Venetian government sent to Padua the custodian of the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice, Jacopo Morelli, with the task of drawing up lists of the objects owned by the monks of San Giovanni di Verdara, who had set up an important library since the 15th century and also kept a remarkable collection of bronzes and medals, many of which once belonged to the great Paduan humanist Marco Mantova Benavides. After Morelli had finished his work, the republic decided to transfer the books and antiquities to the Marciana, while the works of art were assigned to the City of Padua, going to form a first nucleus of the future civic museum (at the time of the acquisition they were arranged in different rooms, but without precise criteria and without yet the exact intention of starting a museum in the strict sense of the term).

The first real civic museum in Padua opened later, in 1825: at that time a significant collection of ancient artifacts, which had originated from the collecting activity of the nobleman Alessandro Maggi, who lived in 16th-century Padua, was kept in the Maggi family palace known as the “Casa degli Specchi” on Vescovado Street. The Maggi’s collection had passed to the City of Padua and in fact formed the first and most important nucleus of the future museum: between 1817 and 1818 a commission had been formed to determine the steps to be taken in terms of the preservation of the city’s heritage, and in 1824 the commission accepted a motion by Abbot Giuseppe Furlanetto, a scholar of antiquities, who had compiled a catalog of the known archaeological assets located in Padua’s territory, proposing to collect it all in one place, suggesting the loggias of the Palazzo della Ragione for this purpose. The commission gave a positive opinion, and the City Council granted the motion: it was 1825, and Abbot Furlanetto organized the transfer of the finds to Palazzo della Ragione and designed the arrangements. The public collection was inaugurated under the title of “museum”(Museo Archeologico, to be precise), although it took an additional three years to finish the transfer of the objects.

In the following decades, the museum experienced a further breakthrough, because the first director, Andrea Gloria (who from 1845 to 1859 was formally the director of the municipal archives: the “Museo Civico” as such did not yet exist), had the idea of also exhibiting the numerous works of art from the churches by the suppressed religious orders (in fact, the orders suppressed in the Napoleonic era were added to those of the Venetian Republic era). It was 1855, and Gloria proposed to gather the works of art in some rooms of the Municipal Palace, later renamed with the name of “Vicariate”: the works that arrived from the suppression of San Giovanni in Verdara, among others, found space here. Meanwhile, the museum’s collection continued to expand: under Gloria’s direction paintings from the Mussato family palace, the collection of notary Antonio Piazza, and donations from various Paduan families arrived at the Civic Museum of Padua. The museum, after the drafting of the Statute in 1858, was officially opened in 1859, the year in which Andrea Gloria thus became the first director of the new Civic Museum of Padua. The works were sorted by artists, special catalogs were drawn up, the museum was opened to the public free of charge, and the City of Padua initiated a continuous policy of acquisitions (in its first eight years of existence alone, the museum received no less than 162 bequests: between 1864 and 1865, in particular, the large donations of Count Leonardo Emo Capodilista, 540 paintings including works by Giorgione, Titian, Giovanni Bellini and others, and Nicola Bottacin, the latter so conspicuous that today there is a dedicated museum, the Bottacin Museum, which houses it and is housed in Palazzo Zuckermann, arrived at the City). In 1880 the museum was moved to larger premises, to a building in Padua’s Piazza del Santo (and in the same year the institute’s first catalog was published), and there it remained for a century, that is, until 1984, when, again for reasons of shortage of space, it was decided to move again, coordinated by Giovanni Gorini and Girolamo Zampieri, to its present location. Since 1985, therefore, the Civic Museum of Padua has been housed in the Eremitani complex.

Today the Musei Civici agli Eremitani are thus divided into two institutions: the Archaeological Museum and the Museum of Medieval and Modern Art. The former occupies the ground floor of the former convent that belonged to the order of the Hermits of St. Augustine and which, after the order was suppressed in the Napoleonic era, was turned into a barracks (it suffered severe damage during World War II: the bombs of the March 11, 1944 raid also severely damaged the church of the Eremitani, where the important frescoes painted by Andrea Mantegna in the Ovetari Chapel are located, and even today, unfortunately, the heavy marks left by the destructive event can be seen). In the layouts designed by Franco Albini, one of the greatest architects active in Italy in the second half of the twentieth century, objects and artifacts narrating the history of Padua from its origins in the 9th-8th centuries B.C. to the 4th century A.D. are admired along nineteen rooms, alternating between Egyptian, Etruscan, Greek and Roman finds.

Of particular interest is the collection of Greek and Magna Graecia ceramics, which originates from the collecting nuclei of the 19th century, and the same goes for the important Egyptian collection, one of the largest in Italy, which includes among its highlights the two statues of the goddess Sekhmet, donated to the city by the explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni, one of the first Italian archaeologists, who had recovered them on one of his trips to Egypt, and who had given them to Padua in 1819, precisely in the years when the first nucleus of the museum was about to be established, with the express request that they be displayed in the Palazzo della Ragione. Splendid reliefs and mosaics form the heart of the Roman collection that chronicles the life of Patavium, one of the richest cities in northern Italy. But that’s not all: the Roman collection also houses an exceptional piece of Syro-Palestinian or Egyptian manufacture, namely a glass bottle with “snake net” decoration found in the center of the city in 1997, in an excavation near the Pediatric Clinic, and which can only be compared to some objects found in the 1930s in Afghanistan. Reliefs, on the other hand, include the stele with Dorotheus and Nice, from the Greek area (1st century AD), which was walled into the facade of a building in Padua, but whose provenance is unknown.

The Museo d’Arte Medievale e Moderna, on the other hand, is the Pinacoteca, which was opened in 1857 by Andrea Gloria, with the aim of displaying to the public the paintings and sculptures that were found in the churches of the suppressed orders and to which were added over the years the works purchased by the City or left by donors. The museum’s itinerary, which finds space in rooms also designed by Franco Albini, proceeds chronologically and houses works from the 13th century to the 18th century. It begins with works from the fourteenth century that include one of the museum’s masterpieces, the series of angels by Guariento da Arpo, twenty-eight panels that were part of the decoration made by the artist for the private chapel of the palace of the Carraresi, the medieval lords of Padua (the chapel was demolished in the eighteenth century). Another great masterpiece is Giotto ’s cross made between 1303 and 1305, at the time when the great Florentine artist was waiting for the decoration of the Scrovegni Chapel (and which in the nineteenth century was hanging right on the apsidal wall of the chapel).

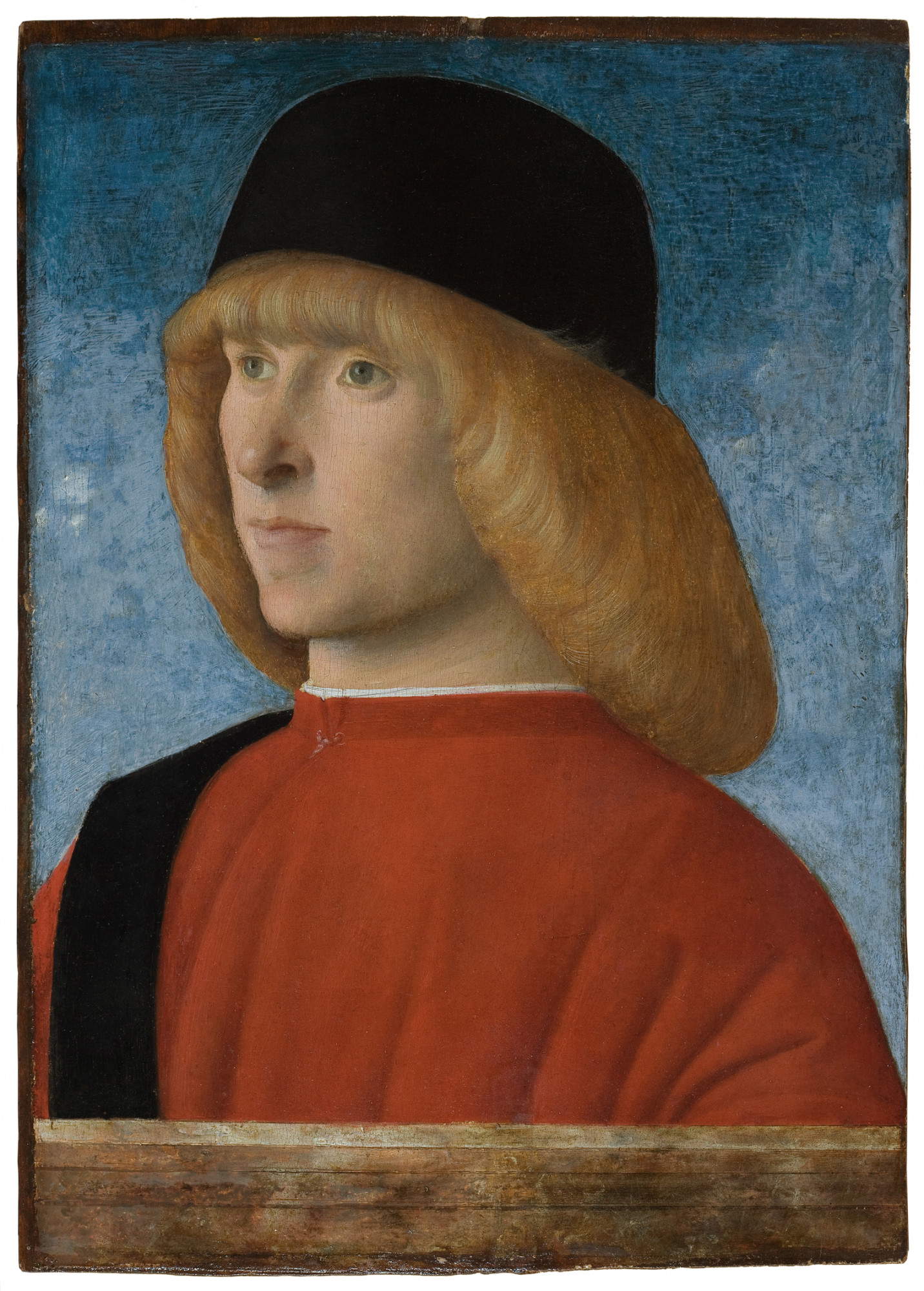

Turning to the fifteenth century, the best-known masterpiece is surely Giorgione’s Leda and the Swan, a work from the late fifteenth century with a mythological subject taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (and by Giorgione is also theIdillio campestre), but one can also admire the Ritratto di Giovane senatore (Portrait of a Young Senator ), which like Giorgione’s painting is part of the Emo Capodilista bequest that became part of the museum in 1864. The great Venetian school of the Renaissance is also evidenced by Titian Vecellio ’s Birth of Adonis and Death of Erisittone as well as numerous other masterpieces such as Andrea Previtali’s Madonna and Child (also extraordinary because in the inscription the great artist of Bergamasque origin declares himself a pupil of Giovanni Bellini), or such as Palma il Giovane’s canvas celebrating the rectors Jacopo and Giovanni Soranzo, or Paolo Veronese’s Martyrdom of St. Justina, one of his major works, made for the Benedictines of Santa Giustina. Also from Santa Giustina, on the other hand, comes Romanino’s splendid altarpiece commissioned from the Brescian painter in 1513 by the monks of the Paduan convent.

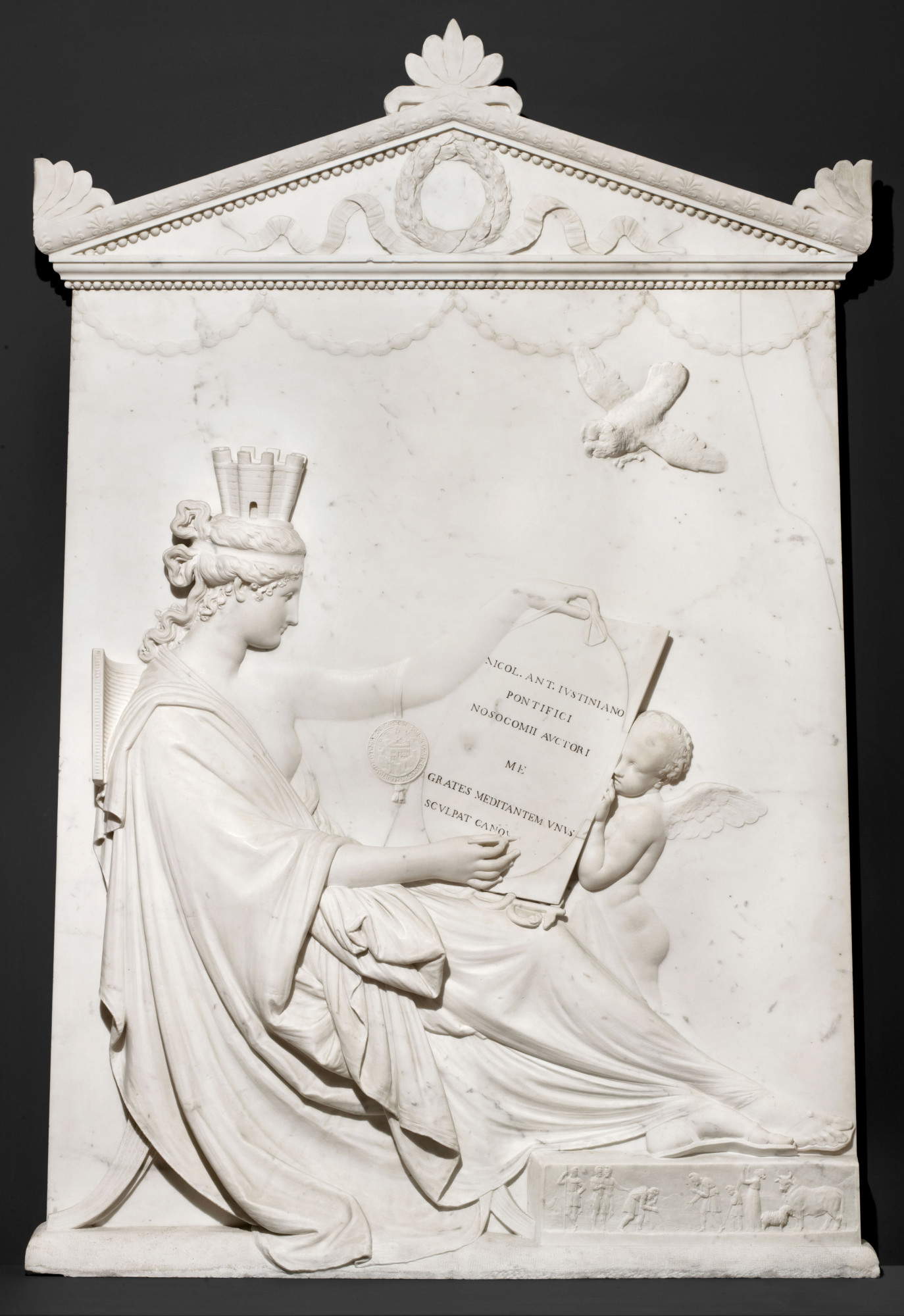

Representing the seventeenth century, on the other hand, are artists such as Alessandro Varotari known as il Padovanino, Pietro Damini, Pietro della Vecchia and other lesser-known artists, and also worth highlighting is an interesting work by the Lucchese Caravaggesque Pietro Ricchi, theIndovina. The 18th-century collections are notable, with two masterpieces, Piazzetta’s The Supper at Emmaus and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s Saint Patrick Bishop of Ireland, which come from the church of San Giovanni di Verdara. Completing the list of great eighteenth-century Venetian painters are Pietro Longhi with his Geography Lesson and Marco Ricci author of several landscapes. Also important is the nucleus of paintings by Giuseppe Zais and those of other Tiepole artists such as Jacopo Guarana and Giovanni Scajario. Then there is a sculpture by Antonio Canova closely linked to the city: it is the Stele Giustiniani, where an allegorical image of Padua is carved. The Eremitani cloister, on the other hand, houses the lapidary, which, through slabs, reliefs and sculptures, tells the story of Padua from the Middle Ages until the fall of the Venetian Republic.

The Civic Museums of Padua today also gather two other museums, in addition to the Archaeological Museum and the Museum of Art. One, it was mentioned above, is the Bottacin Museum: it is housed in Palazzo Zuckermann and named after Nicola Bottacin, who donated his collection of artworks and coins to the City of Padua in 1865. Set up on the second floor of the palace, it is a museum dedicated primarily to numismatics and art, particularly the applied arts, with an itinerary divided into two sections that reflect the great collector’s main interests. The works of art include paintings and sculptures by 19th-century artists from Veneto (and elsewhere), while the medagliere houses rare and remarkable pieces including the gold ducat of Francesco I da Carrara (the only one found in a public collection), Renaissance medals, and the section on the history of coinage, a part of the museum that has few equals in Italy. The second institute is the Museo del Risorgimento e dell’Età Contemporanea (Museum of the Risorgimento and Contemporary Age), located in the rooms of the Piano Nobile of the Stabilimento Pedrocchi and dedicated to the history of Padua and Italy from the fall of the Venetian Republic to the promulgation of the Italian Constitution on January 1, 1948. The choice of the location is due to the fact that on the Piano Nobile of the Caffè Pedrocchi, on February 8, 1848, students from the University of Padua gathered to rise up against the Austrians, in the antecedents that would later lead to the First War of Independence. The museum today collects documents, memorabilia and works of art that tell these one hundred and fifty years of history.

Finally, it should be noted that several monumental venues are also part of the institution of the Civic Museums today, starting with the Scrovegni Chapel, located a few steps from the Eremitani complex, and continuing with Palazzo della Ragione, the Oratory of San Michele, the House of Petrarch, the Oratory of San Rocco, the Loggia Cornaro and the Clock Tower. The museums’ recently renovated website is an excellent starting point for a visit since within it one can find the fact sheets of all the museums and also databases with selected pieces from the collections, accompanied by accurate and comprehensive descriptions and high-quality images. Thus can begin one’s journey through the Civic Museums of Padua: to begin it is to go back in time and travel through the history of the city.

|

| From Giotto to Tiepolo: masterpieces from the Padua Civic Museums tell the story of the city |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.