We have reached the third-to-last leg of our journey to discover animals and fantastic places in Italian museums. For this chapter number eighteen of our itinerary we move to Sicily: here is what we found on the island. The project is led by Finestre Sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture to let the public discover museums, safe places suitable for everyone, from a different point of view.

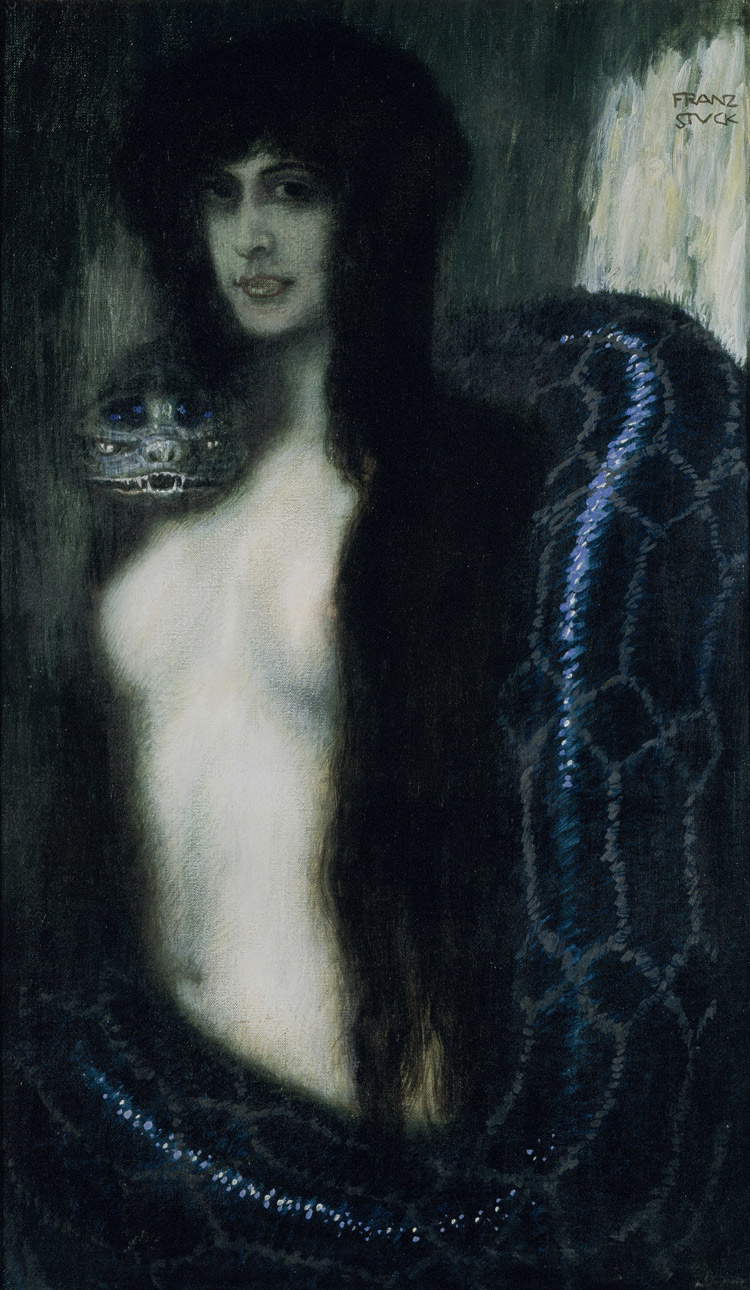

The Sin by German Franz von Stuck (Tettenweis, 1863 - Munich, 1928), one of the greatest artists of European Symbolism, is one of the most intriguing works by this important painter. Von Stuck depicts a beautiful, bare-chested woman, veiled in subtle eroticism, who is being entangled by a disturbing snake that looks the viewer straight in the eye: it is the devil tempting the woman, in a clash of Good and Evil that is at the heart of the meaning of this painting. Eleven versions of this work exist: the one in Palermo was purchased specifically for the Modern Art Gallery of the Sicilian city when the artist exhibited it, in 1909, at the 8th Venice Biennale. The work is framed by a large frame with two columns at the base of which is the painting’s title in German: Die Suende.

The “Antonino Salinas” Archaeological Museum in Palermo preserves a beautiful balsam bowl in the shape of a mermaid: it was a container in which ointments and body balm were stored. Balsam jars could take a variety of shapes: in this case it has the likeness of a mermaid, the creature who, according to ancient mythology, had half a woman’s body and half a bird’s, and was able to entice sailors with her melodious song. The balsamarium in the Palermo museum, which has a shape that is not unusual (the mermaid takes on the appearance of a passerine, with a very elongated body, and legs hidden under the belly, while the face, that of a beautiful woman, observes the object’s possessor), comes from the temple of the Malophoros in Selinunte. The balsamarium was probably made in a workshop in Rhodes and then took the road to Sicily at the time when the island was a Greek colony.

According to Greek mythology, the doe of Cerinea was a fabulous doe with golden horns and silver and bronze paws, who had the ability to flee those who chased her without ever stopping, while at the same time enchanting the pursuer, who was thus dragged far from home with no possibility of return. Also according to myth, she was captured by Hercules, who freed her in Mycenae since, being an animal sacred to Artemis, she could not be killed. At the Archaeological Museum in Palermo there is a sculptural group found in 1805 in Pompeii, in the House of Sallust, and arrived in Sicily most likely when Ferdinand I of Bourbon was exiled from Naples in the Napoleonic era. It was then donated in 1831 to the Museum of the University of Palermo, and in 1866 it was transferred to the Museo Nazionale dell’Olivella, or the current Museo Archeologico Regionale “Antonio Salinas,” where the bronze group is still on display. A work of great refinement, datable between the end of the first century B.C. and the beginning of the first century A.D., it depicts Hercules holding the doe by the horns.

The Satiro vers ante preserved at the Archaeological Museum in Palermo depicts a satyr, a mythological being half man and half goat, which, however, in this work has the appearance of a beautiful young man: one can tell it is a satyr only by the presence of the pointed ears, like those of a goat, typical of these legendary creatures. It is an ancient copy (from Roman times, the first century AD) of a Greek original by Praxiteles: the Satyr on the side is the earliest known work by the great Greek sculptor, the leading figure of the late classical period of Greek sculpture. The Palermo work was found in 1797 in the ruins of Villa Sora in Torre del Greco, and was later donated by Ferdinand II of Bourbon to the Archaeological Museum of Palermo. The satyr is depicted lifting an oinochoe, or wine jug, to pour the contents into a kylix, a drinking cup. One finds in this sculpture all the main characteristics of Praxiteles’ art: the harmony of proportions, the almost expressionless face, and the delicacy of the body.

The scene of the blinding of Polyphemus, which appears on this sarcophagus fragment preserved at the Ursino Castle in Catania, is taken from Homer’sOdyssey: Odysseus gets the Cyclops Polyphemus, who was holding him and his companions hostage, drunk and waits for him to fall asleep in order to blind him with a red-hot pole. In the Castello Ursino fragment, the cyclops is in the center of the scene, lying down: according to mythology, cyclopses were gigantic beings (in fact, the proportions of his body are larger than those of the other characters), endowed with only one eye. Odysseus is above him, wearing the cap that identifies him as commander or ruler (he was king of Ithaca), while his companions assist him to complete the task. Executed in yellow marble, the relief, from the imperial age, nevertheless shows a peculiarity: the cyclops is depicted here with two eyes, probably to make his figure more “human.”

The “Paolo Orsi” Regional Archaeological Museum in Syracuse preserves a very ancient painted terracotta, dating from the 6th century B.C., depicting the gorgon Medusa, formerly located in the city’s Temple of Athena. The monstrous creature is depicted according to typical iconography: a ghastly face, mouth with fangs and tongue out, long hair with a parting in the middle and curls on the head, eyes wide open, and two large wings. The Medusa of Syracuse also holds under her arm the winged horse Pegasus, which according to legend was born from her body after she was defeated by the hero Perseus. Depictions like this located in religious buildings were meant to ward off evil. Often of the Gorgon, however, only the face was depicted: the uniqueness of the Syracuse Medusa lies mainly in the fact that we see the monstrous being depicted in full.

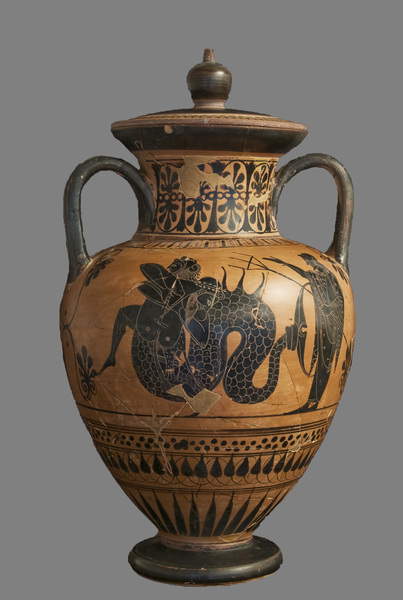

This painted black-figure amphora preserved at the Archaeological Museum of Syracuse is the work of the so-called Pasikles painter, dates from about 520 BCE and was found in the necropolis of the former Garden of Spain in Syracuse, specifically in the grave goods of tomb 4. The depiction is rare and singular: in fact, we see Heracles fighting with a sea deity, Triton, son of Poseidon (the god of the sea), equipped with a fish-shaped body, and with a human face. The fight with Triton is not part of the Twelve Labors, and scholars have long debated depictions such as this: the first to write about a fight between Heracles and Hálios Géron (the “old man of the sea,” an unspecified deity) is the Greek writer Ferecides of Syrus, and it can be assumed that this account was the source of the artists who depicted the hero engaged in this fight. A struggle that we imagine subsequent, at least, to the first effort, since Heracles wears in the amphora the skin of the Nemean lion, defeated in the first of the twelve feats.

Exactly like the Pouring Satyr of Palermo, the Dancing Satyr of Mazara del Vallo, housed in a museum entirely dedicated to it, has no animal legs, and can be recognized only by the shape of its ears: in fact, the Mazara work was also made at a time in history when Greek sculptors intended to humanize figures like this one. Attributed to the school of Praxiteles, the statue was found in 1997, when the leg was identified (this was followed in March 1998 by the discovery of the body and arms). It was then put on public display starting in 2003. The statue was probably part of the cargo of a ship that was wrecked off the coast of Sicily. The legendary creature is depicted in the act of dancing since satyrs used to accompany, precisely with wild dances, the processions of Dionysus, the god of wine. We can imagine the statue complete with kantharos, a special wine goblet. The satyr is larger than life-size, as his standing figure would reach a height of two and a half meters.

According to Greek mythology, Scylla, daughter of Typhon and Echidna, was one of the most beautiful of the naiads, the nymphs of the sea. There are several versions of the myth, but they always end the same way: someone punishing Scylla by turning her into a horrible monster (Circe to punish her because the god Glaucus had fallen in love with Scylla by rejecting her, or Amphitrite, jealous because her husband, Poseidon, wanted her for himself). Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (Florence, 1507 - 1563), an important Tuscan sculptor and a collaborator of Michelangelo, made this sculpture for the Fountain of Neptune in Messina, completed in 1557: this was the second fountain Montorsoli made for the city, after the Fountain of Orion. However, during the uprisings of 1848, the fountain was damaged and it was the statues of Neptune and Scylla that got the worst of it, which were replaced in the square by two nineteenth-century reproductions (Gregorio Zappalà took care of Neptune in 1856, while the one of Scylla was executed by Letterio Subba in 1858), and admitted to the Regional Museum of Messina where they can still be admired today.

The Ear of Dionysus, also known as the Ear of Dionysius, is an artificial cave carved out of the Paradise Latomia quarry (the “latomie” were precisely stone or marble quarries where slaves or prisoners of war worked, and for that reason were also used as prisons). About 23 meters high, the Ear of Dionysus has a development in depth of 65 meters, which makes it particularly suitable for amplifying sounds (and precisely because of this characteristic there has long been debate about the real function of this place). According to a myth reported by local tradition but without foundation, it was the painter Caravaggio, who was present in Syracuse in 1608, who gave this name to the cave, since the shape reminded him of that of an ear. The “Dionysus” referred to is the tyrant Dionysus I (or Dionysius) of Syracuse (430 B.C. - 367 B.C.): again according to legend, the city’s ruler would set himself up on top of the cave to listen, thanks to his ability to amplify sounds, to what the slaves working there said.

|

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Sicily |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.