It is not a fad. It is not even a comeback. It is a slow infiltration, a trickle that has become a river. For the past few years, contemporary art seems to be crossed by a different whisper, something that resembles prayer but behaves like a wound: it does not close, it pulsates.

What are so many women artists looking for today among constellations, rituals, astral bodies and ancient symbols?It is not just fascination for the occult. It is a form of knowledge. An embodied practice. A survival strategy, perhaps. Increasingly, in studios of young women artists and queer people, one sees tarot cards, astrological grids, crystals, magic texts, Kabbalistic diagrams, drums, antennae, quartz spheres, invented languages. The supernatural, the mystical, theesoteric return, but this time with a specific purpose: to deconstruct.

There is something, indeed, that is disintegrating. Or perhaps it is something that is emerging from beneath, that has always been there, silenced. Contemporary art is experiencing an opening toward the invisible, toward what rational, white, patriarchal modernity had called crazy, childish, primitive. But if rationality has come at a price, if it has meant domination, epistemic colonialism, control of bodies and minds, then going astray can be an act of resistance.

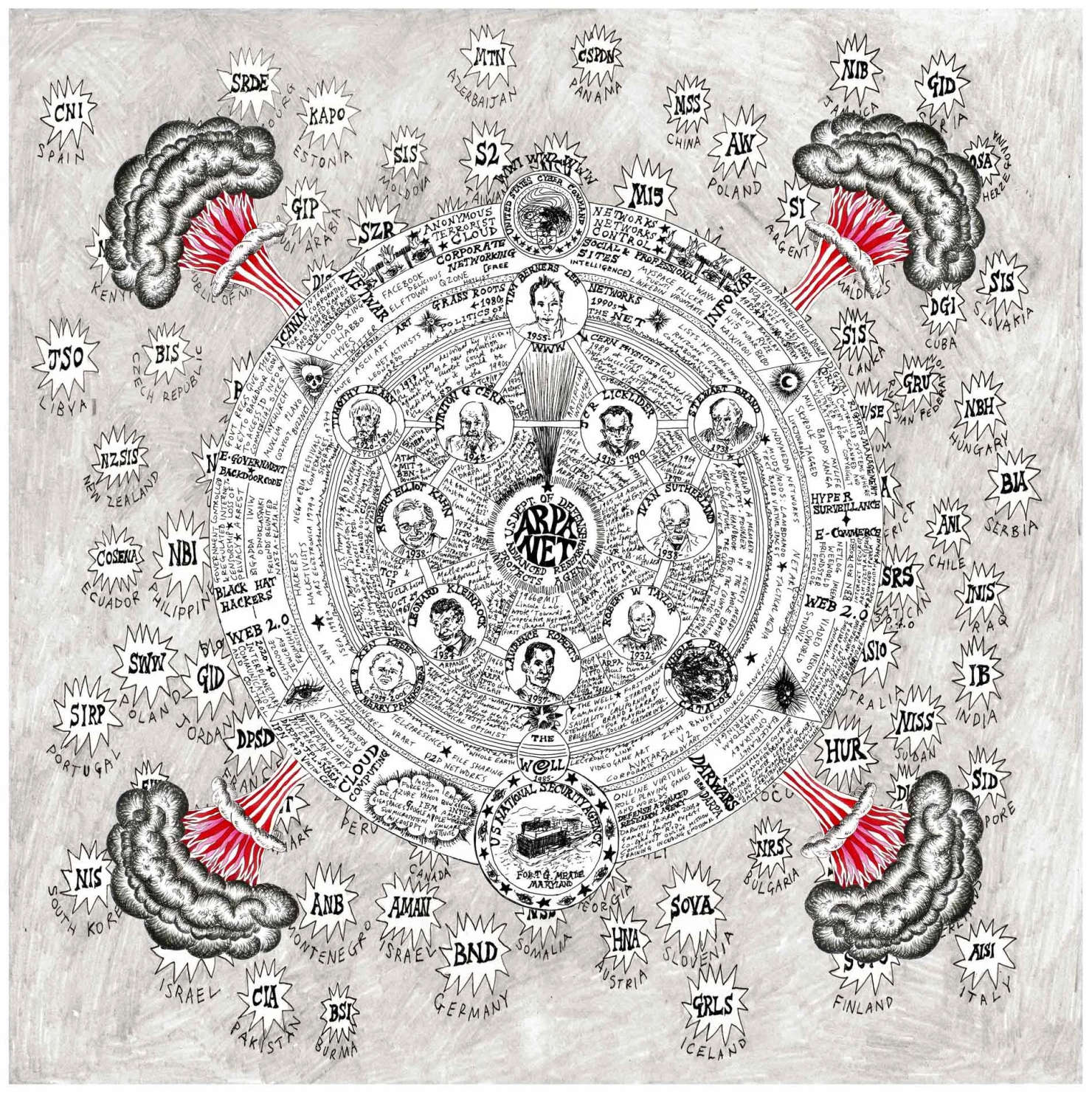

Suzanne Treister, a pioneer of occult thinking from a techno-esoteric perspective, knows this well. Her works resemble alchemical scores: maps, algorithms, interdimensional grids in which psyche, power, drugs, financial systems, psychoactive plants, digital mythologies are intertwined. His HEXEN 2.0 series (2009-2011) is a hallucinatory and perfectly lucid chronicle of the post-war West: tarot card-style diagrams that fuse cybernetics, social control, psychedelic culture and counterculture. It is as if he is saying: to understand the present we must summon the spirits of technologies, read systems as if they were entities. But who has the right to “divine” today?

Tabita Rezaire, a French-Guianese-Danish artist, pushes us further. In her hypnotic videos, in her digital portals vibrating with sacred frequencies, Rezaire constructs an alternative cosmology. A black woman, queer, healer and living “interface” between ancestral and digital, she weaves together the knowledge of African communities, energy medicine, astrology, vibration, female spirituality and colonial heritage. In Premium Connect (2017), for example, she connects the undersea cable of the internet with the spine, with Africa, with the stars. The body becomes an antenna. So then: can the queer body heal the fracture of modernity? Can art be a form of medicine?

In this field, ritual is not decoration or spectacle. It is language, it is code. It is what precedes the word and goes beyond it.

Jesse Darling, winner of the Turner Prize 2023, works instead with scraps, poor materials, and wounded objects. His sculptures look like relics of a post-systemic world, fragments of a secular and marginal cult. Wheelchairs as sacred thrones, crosses constructed from crutches, broken and stitched religious symbols. Spirituality here is weak, vulnerable, queer. It does not manifest itself in mystical visions, but in the pain of the disabled body, in the collapse of certain signs. There is a form of sacredness in the precariousness, as if only that which falls can really begin to feel. Then it becomes clear: these are not escapes from reality. They are other ways of inhabiting it.

Ritual, spirituality, esotericism are no longer territories of the “past” or “folklore.” They are tools. They are picks to unhinge epistemologies that have excluded, hierarchized, medicalized, destroyed. And who better than those who have been historically marginalized -- women, queer people, diasporic subjectivities -- can use these tools to rewrite the real?

Magical practice is not necessarily a return to religion. It is often the invention of one’s own sacred language. Art, in this sense, becomes a personal liturgy. But not individualistic. Ritual is always a gesture toward the other, visible or invisible. A new genealogy is thus drawn. From Hilma af Klint to Ana Mendieta, from Claude Cahun to Genesis P-Orridge, art has always had border zones, porous, fluid. Today, those zones are widening. New spiritualities do not seek answers: they activate questions. What does it mean to heal today, in the time of surveillance and algorithmic solitude? What is a sacred body, if not that which resists categorization?

Behind every hand-drawn tarot, behind every urban shamanic performance, behind every astrological map stitched together with chants and glitches, lies a political gesture. Not shouted, but powerful. It is not about believing or not believing. It is about listening.

Art, in these practices, does not represent: it invokes. It does not just construct meanings but opens portals.

And so perhaps this is what is happening before our eyes: the emergence of a post-materialist, post-identitarian spirituality, a queer, diasporic, diffuse liturgy that has no temples but many altars. Do we recognize them? Are we still able to enter a sacred space if that sacred is unstable, strange, misunderstood? If that sacred looks at us from within, and not from above?

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.