The Covid break allows for a few digressions such as the one that follows here, and of which the reader will forgive me. This year’s dazzling Raffello exhibition, luminously curated by my friend Marzia Faietti, not only gave me the opportunity to repeat the tour with somewhat interested people, but also granted me the return for repeated visits to the Vatican Stanze. And here, in front of the “School of Athens,” the insidiousness of the details popped back into my mind, the stimulus of the search drill on lost corners of the monumental scenic amplitude, worthy indeed of a grand-opéra, within which the young Urbino makes the choral masses of philosophers and geniuses move as in a supreme entelechy of the highest knowledge.

|

| Raphael, School of Athens, fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican (1508) |

|

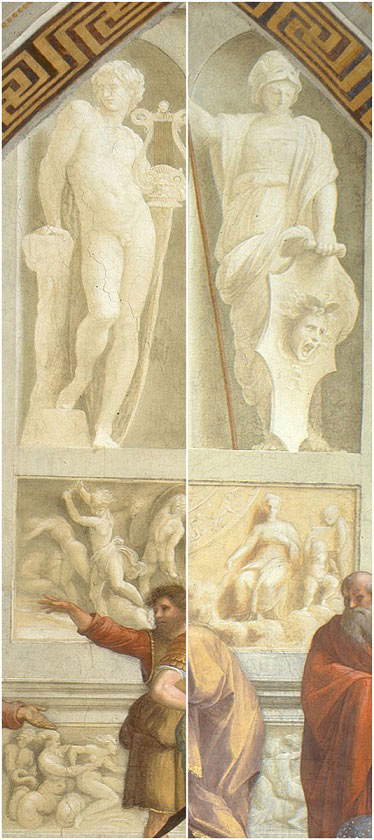

| Raphael, monochromes on the median backdrop of the School of Athens. Vatican Rooms (1508) |

Here’s my question: what are those agitated nudes doing under the languid hips of Apollo awaiting applause from Muses for the poetic song he has just issued? Mind you: we see that the two tenuous monochromes of the god Pythius and Athena, placed by Raphael to protect the thoughts of the Sages, stand there on the walls in their respective niches. The two Numi appear above marble panels that bear some figures of no easy decryption, about which critics have been unwilling to offer clear revealing words. A single brief passage of text once said that they should be “antinomies”: that is, under the heavily armed Athena one could grasp an invitation to peace, and under the lyrical Apollo musagete, all devoted to the harmonious arts, one is called to see the perversity of violence and the opportunity to conculcate it. A small key that prompted me to delve deeper into this last painting, which evidently appears to be taken, or inspired, by an ancient Roman marble. There are five male nudes, and in addition there is a female scream of protest. The protagonist, equipped with a short serrated cudgel (so it seems) is beating an individual who has already fallen to the ground lying down; since these are nudes we might agree with the idea that this is a clash of an ideal-symbolic character to which the decisive punishment of a vanquished person is the centerpiece. The two nudes on the left are also retreating, while the woman opposes those who want to use weapons and bullying. If we connect the fight scene with the one below, which shows a triton’s attempted violence against an elusive nymph, the (all-Renaissance) concept of the “punishment of the senses” seems most plausible.

|

| Titian, Detail from Sacred Love and Profane Love (1515; oil currently on canvas 118 x 279 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

The thesis becomes particularly strengthened by a similar scene, again in faux marble high relief, that Titian a few years later affixed to the front of the “Love Tub” where equally there is a brute punished for a sexual attempt, as evidenced by the naked, invoking woman in the background. In this case the blows of the snapping execution are directed exactly at the butt of the offender. That part of the body, which our ancestors referred to as “brainless,” thus becomes symbolic of instincts, yet still capable of receiving and transmitting frigid sensations.

|

| Marble group formerly on the edge of the pool of Poppaea’s villa at Oplontis. 1st cent. b. C. |

Among the ancient sculptures of the Classical period are various scenes of sexual dissension, between lustful rough males (fauns, sàtiri, tritons, etc.) and unwilling nymphs or maidens. This group, possibly descended from an animated Hellenistic composition, we show here to confirm the “Roman” inspiration Raphael must have had. Indeed, the small monochrome of the School of Athens has been studied with precise, almost insistent elaboration by the Master of Urbino.

Our attention now turns, quite necessarily, to the formalities of punishments among the Latins. Corporally they were reserved for males. In the military sphere they were cruel, and we do not care for them. In the civilian sphere, if we disregard slaves, it appears from iconographic documents that they were not applied to cives, but always and frequently to pre-adolescents and adolescents during their formative period. “Theoretical” schools and gymnasium schools were the scene of this, hence the evidence, including visual evidence. With certainty we know that good families at the appropriate time entrusted their little ones to the masters, that is, to the managers of the schools, which were always private and fee-paying, demanding from them both the results of learning and (and it seems above all) the formation of a squared-off character, well forged by strokes of the stirrups. The poor bare behinds of the youths bore the sum of such interventions, and moreover the tradition, as well as biblical, was very ancient: in Greece the “punishment of the sandal” and then that of leather stripes had been in force for centuries; in Rome there was a kind of graduation of school whippings: from the ferula to the virga to the scutica (alas!!). Several Roman writers recall the treatment received by plagose teachers, that is, blistering. We thus present the public sign of a Pompeian school, which served as a great attraction for families who wanted excellent results.

|

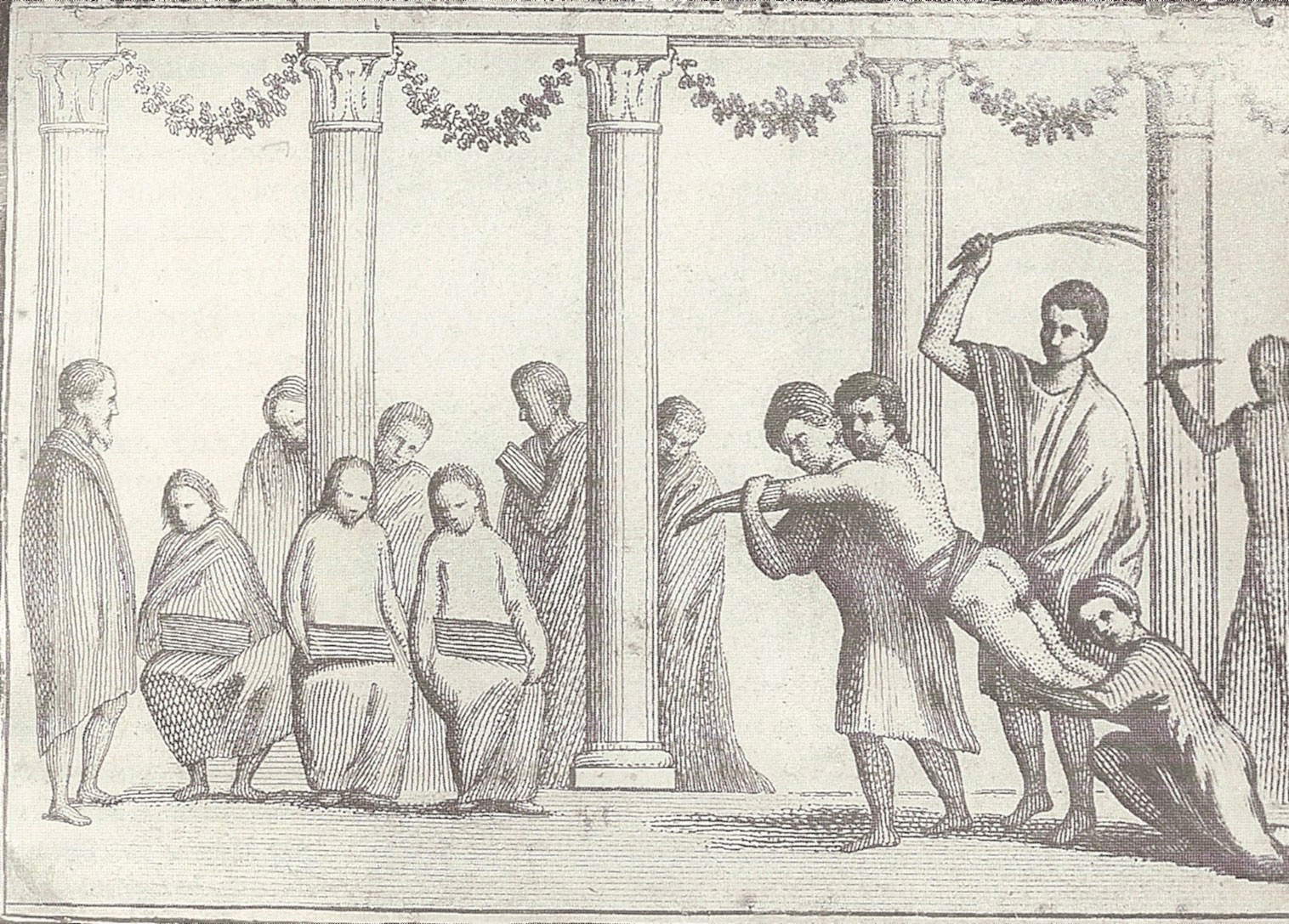

| Sign of an ancient Roman school, from Pompeii. Drawing from the fresco. (See “Rome, Museum of Roman Civilization”). |

The environment is very noble. The judicious students hold the tabulae on their knees, while the restless boy is in the well-known position of catotum, a slang word that meant “to stand on the shoulders.” In fact, a stout fellow is obliged to hold him on his shoulders and a tall one to hold his feet still: the position is obvious, and it is the master himself who intervenes to administer the punishment, which, if anything, will be continued by the orderly who follows. All this as a public manifesto!

In the Middle Ages, where punishments for adults were too often very harsh, education also involved corporal pain, but documentation is scarce. An unexpected echo of this remains at the height of the Renaissance (1474) in the first of Benozzo Gozzoli’s frescoes where the painter illustrates the life of St. Augustine. Here the parents have already entrusted the willing little Augustine to the celebrated master of Tagaste, who benevolently holds him close as he administers to the disobedient child (who is already “on his back”) the salutary and well-known nerbs.

|

| Benozzo Gozzoli’s fresco in the church of Sant’Agostino in San Gimignano. Detail. |

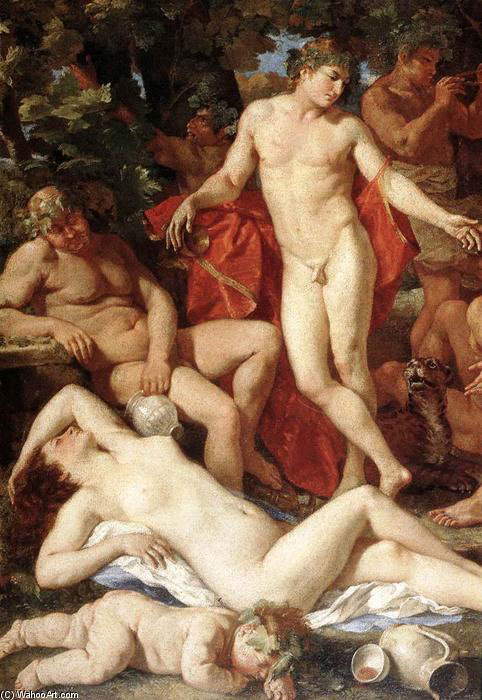

In the modern centuries (seventeenth and eighteenth centuries), scholastic figures of punishment almost disappear altogether; but the subtle vein of “reprobation of the senses” slips to a fairly widespread marginal florilegium of canvases and canvases, engravings, ceramics and a few sculptures, bearing the scene of Venus punishing Love. A decidedly literary and ideological topos, without pain, where the Goddess effectively reprimands the improvident Cupid, the cause of senseless love affairs. This was already the case, moreover, in the Pompeian frescoes.

In Tiarini’s painting, the courtly Aphrodite becomes a Po Valley mother, and the beating takes place according to the inveterate method and posture of our grandmothers. In the next detail from Poussin, who is very attentive to ethical themes, we can mimic the disappointing results of Cupid’s escapades, who here has gotten everyone drunk and is lying on the ground, also now tipsy.

|

| Alessandro Tiarini, Venus Spanks Cupid (1630; canvas 161 x 132 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Nicolas Poussin, Detail from Bacchus and Midas (ca. 1630; Munich, Alte Pinakothek) |

|

| Gaspero Bruschi, for the Doccia manufactory, Venus Punishing Amore (1745-46) |

The delightful clusters of small ceramics were also gladly welcomed on the tables of wealthy families, and the seemingly fatuous theme of a distant mythology revealed a very firm belief that wanted lineages well regarded, and marriages not dictated by amorous impulses, but determined strictly by the interests of each family. This allows us to turn to an almost surprising painting by the Viennese painter Adam Johann Braun (1748 - 1827) who often worked as an illustrator of the social life of his city. The subject matter, so explicit, is rare, and we do not know who commissioned it: perhaps a family of irreducible morals (as a cautionary exemplum for growing daughters), or perhaps by the abbess of a very strict women’s college in which the rules (!) forbade the educating girls of the noble prosapies any amorous inclinations, with corresponding precise and sensitive punishments (!). It does not matter to know this because the purpose was unique: the Collegial girls were placed at the monastery for the sole purpose of formal education, segregated from deprecated and forbidden male approaches, and reserved for future marriage decided by the master father.

|

| Adam Johann Braun, Maedchenschule (The High School), 1789. Unknown collocation |

Here a punishment is involved, but carefully and almost movingly elaborated. The setting is that of a bygone women’s boarding school, dedicated to noble maidens. Here the Regentess, or Abbess, according to strict regulations and in accordance with the duties of the office, had to administer by her own hand the compensations for the mistakes of the educating girls. The scene hints at an event: the supercilious maiden has done wrong (the tattered note on the floor is meant to point to evidence of a princely love affair), and the Abbess intervenes, reminding her with what punishment she must now make amends. But it seems (shall we say) that the first part of the conversation was followed by the admission of guilt and the request for forgiveness; the girl is induced to say a prayer of repentance before the small study altar, urged on and accompanied by the Rectress. In fact, it is soon afterwards that leducanda herself spontaneously arranges herself in a befitting manner on the altar step to receive her due chastisement, and well exposes the auroral surfaces on which the swipes of punishment will be impressed. The whole is very moving: the Superior holds the rods with which she will leave the various marks on the tender cluni. Trembling remain only the Miss’s attendants, who may have already prepared the soothing ointments, but the atmosphere really rises to a poetic breath of achieved fairness. Conversely, the feeling is that shortly afterwards the noble educanda, while retaining the burns of the case, wants to reintroduce herself to her fellow boarders with an air of surpassing, as befits one of her rank. She retains her beautiful dresses and jewelry for this. She will process the burns as she goes, from skin to memory.

For our part, nothing more to say about the skit, except to recall the grand virtude de li tempi antiqui when our grandmothers poured out their speeches to us without any thoughtful ceremony, with firm holy hands. Now the almost unanimous universe of Western pedagogues excludes touching babies, grown-ups, and pimply youngsters: that they grow up like that, with their virgin butts.

But the staggering spread of bullying and pack formation, where physical violence becomes the continuous practice and causes the ruin of so many other weaker and more precious young people, and comes to very serious episodes and crimes, does it tell us anything? Every day we witness news reports and legal impotence on even public youth fights, physical persecution, violence against women and children, devastation of cultural property! And what do we do? Here in the West, could we not return to a sacrosanct, and just, and useful, ancient practice? Would Raphael want to teach us again?

The author of this article: Giuseppe Adani

Membro dell’Accademia Clementina, monografista del Correggio.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.