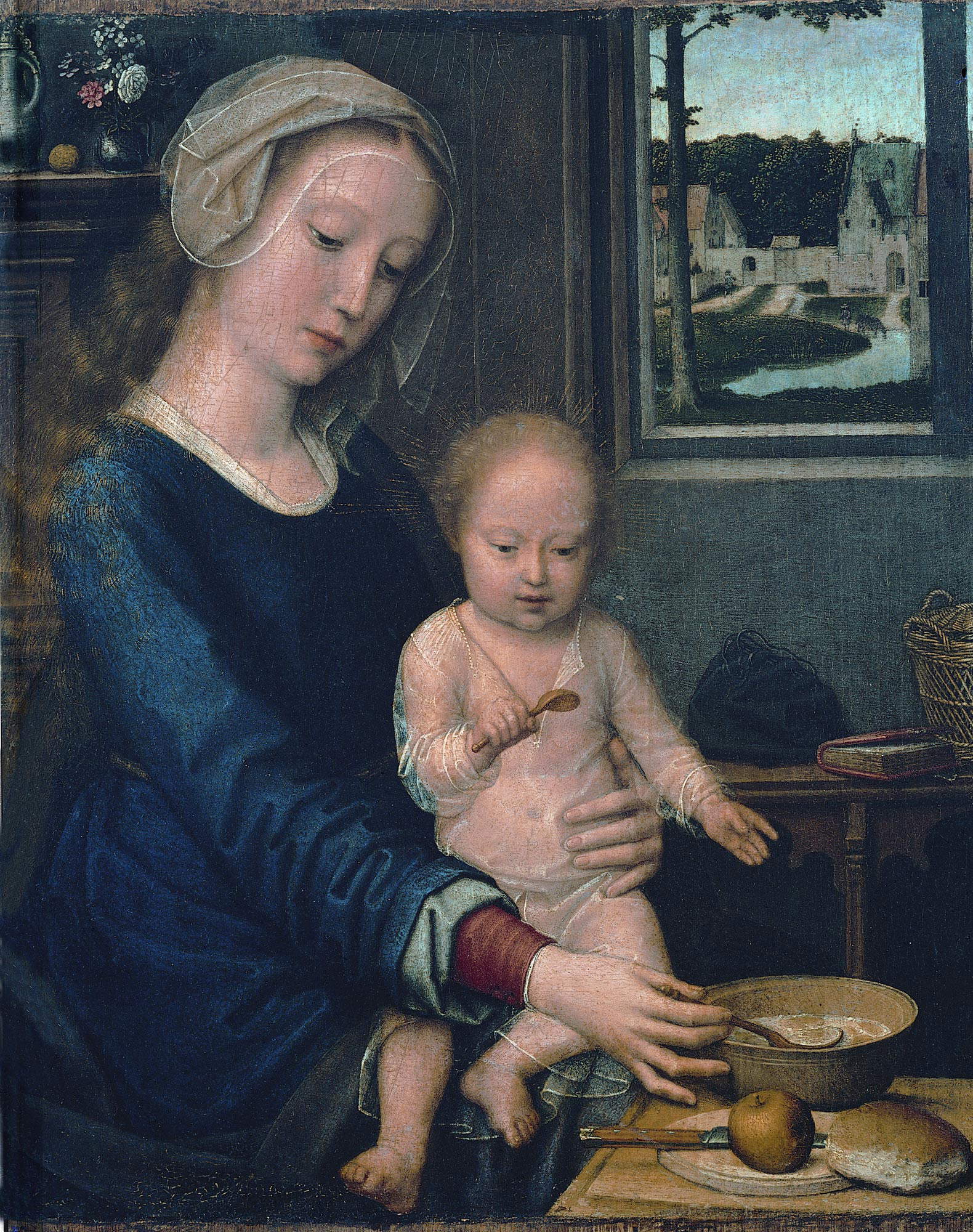

One does not necessarily have to think of childish romanticisms when, in the first room of the Flemish in the Palazzo Bianco in Genoa, one reads the caption accompanying Gerard David’s splendid panel on the right wall and notices that someone chose to call it Madonna della pappa. Already in eighteenth-century Tuscany a Madonna by the Sienese Francesco Vanni was known by this name, since, explained historian Giovanni Gori Gandellini in his Notizie istoriche degli intagliatori, “with a spoon she administers food to the Child Jesus.” The term “pappa” here stands simply to denote the nourishment given to children: in ancient times there was no other usage of indicating that bread-based food cooked in milk that sustained the little ones just after weaning, so much so that in Tuscany it later came to commonly designate any soup prepared in the same way (think pappa al pomodoro).

So, to see a work like David’s called Madonna della pappa certainly did not sound puerile. It is true, then, that this nuance is completely absent in the English titling: outside of Italy we speak of a Virgin and Child with the milk soup, a decidedly less expressive designation. It should be specified that seven versions of the Madonna and Child by David are known, the best of which is the one in the Aurora Trust in New York, which has been better preserved than the others and is distinguished by a more accurate and higher quality pictorial drafting. The basic pattern, however, remains unchanged, just as the models remain unchanged: Gerard David looked to Italy, he looked to Leonardo’s, for example to Bernardino de’ Conti’s Madonna del Latte , preserved at the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, pointed to by art historian Maryan Ainsworth as the most likely precedent, although all roads inevitably lead to Leonardo da Vinci’s Madonna Benois .

So, for Englishmen and Americans, Gerard David’s work is the “Madonna and Child with Milk Soup.” However, with this title one is automatically led to wonder what milk soup is, what it is for, what relationship it has to the Madonna and Child. “Soup,” on the other hand, is infinitely more flavorful vocabulary than the aseptic “milk soup” of English speakers. It is the way children since ancient times have called bread, with the repetition of the first syllable typical of the lallazione. There is thus in “gruel” a semantic reference to bread, present moreover on the table that David places in the foreground, with a further reference to Christ’s sacrifice, which milk soup fails to express. Just as “gruel” is more immediate in conveying to us the idea of the Virgin who is feeding the Child, an image that could also be read as an allusion to the Church sustaining its faithful, not already according to the concept of Mary mater Ecclesiae, of which only scanty evidence can be found in the liturgical documentation of the time (of Mary as mother of the Church, moreover, would begin to be spoken of extensively from thenineteenth century before, and the title would be proclaimed only in 1964, by Paul VI), but simply on the basis of the analogy between Mary’s maternal role and that of the Church, an analogy of which ample evidence is found in patristics. In St. Augustine’s letter to Leto, for example, we read that “the Church is your mother. [...] it was and is she who nourished you with the milk of faith, and while she prepares a more solid food for you, she sees with horror that you want to remain wandering like toothless sucklings.” And then, Ainsworth noted again in his monograph on Gerard David, Our Lady of the gruel could be linked to the writings of some medieval theologians, such as Hildegard of Bingen, Elizabeth of Schönau, Catherine of Siena, and Juliana of Norwich, who in their works referred to women to signify the whole of humanity, and to motherhood as a symbol of the love and nourishment the soul receives from God. “It behooves us to do,” wrote Catherine of Siena, for example, “as the child does, who, wanting to suck milk, takes his mother’s breast, et se mette it in his mouth; so that by the means of the flesh he draws the milk to himself. So must we do, if we wish to notricate our souls; for we must attach ourselves to the breast of Christ crucified.”

Of course, Gerard David’s Our Lady of the Meal will also have to be interpreted literally, as a tender and affectionate image of a mother who is trying to get the Child to eat: we see her gently holding him on her lap, holding him with her left hand so that he does not fall, and picking up a spoonful from the bowl with her right. We can picture her as she shortly begins to feed the Child, who appears curious, almost amused, while in turn, to imitate his mother, she holds a teaspoon in her little right hand. The scene is set in a Flemish domestic interior: above left, a still life piece with a pewter jug, an apple, and a vase of flowers. Behind, objects that could be found in a house of the time: a basket, a book, a sack. Behind the Virgin and Jesus Christ, a window opens onto a city divided in two by a river that runs through it, with a tree serving as a backdrop on the left.

At first one might therefore think almost of a kind of genre skit, capable of satisfying the expectations of a private patron who, in the sacred icon, wanted to see a familiar, spontaneous, engaging image. It is not conceivable, however, that Gerard David kept away from any attempt to graft symbolic allusions into every single element of the scene: every minute detail of his composition hints at a further dimension. In the New York painting, for example, on the door of the sideboard can be seen the depiction of Adam, absent in the Genoese version: David thus presents us with the Virgin as the new Eve and Christ as the new Adam, as together they repair the disobedience of the progenitors, all the more so that in the Aurora Trust painting the Child, instead of the spoon, holds a sprig of cherries, a further reference to the fruit of original sin. The flowers behind the Virgin hint at Christ’s death and his mother’s grief, while the jug could be read as a Eucharistic symbol hinting at wine and thus Christ’s blood. The basket with cloths recalls the shroud with which Jesus’ body was wrapped in the tomb, and perhaps also to make this reference more immediate Gerard David may have decided to dress the Child in a smock in the Genoese painting, when in the New York one he is naked. The book takes us back to the devotional practices of the time, while the objects on the table reveal the overall meaning of the painting, an allegory of incarnation and redemption: the fruit in the foreground is a direct allusion to the original sin redeemed by Christ through his death on the cross, to which the knife refers instead.

The Genoa version, where the painting has been present since 1874, purchased in Paris by the Brignole Sale family for their collection and then passed to the city by legacies, is less laden with allegorical undertones than the New York version, and was certainly intended for a less demanding patron. A patron who was able to recognize, yes, the theological implications of the Madonna della pappa, and who naturally saw in this mother a model of virtue signaling the value of the family in early 16th-century Flanders, in a society that was abandoning its old models based on agriculture and the collective dimension of social life, and beginning to develop a new bourgeois and capitalist paradigm within which the role of the family and the individual took on entirely different merits. But probably the patron was also eager to see a closer, more human, more earthly Virgin. He was perhaps looking for a more immediate dimension, the same one that most fascinates most of those who see Gerard David’s Madonna of the Loaf in Palazzo Bianco today. In a word: a mother. A loving mother caught in an intimate, natural gesture that touches the heart and moves human beings of the twenty-first century as it touched those of the sixteenth.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.