In an interesting account of a trip to Italy written in 1766 by Scottish painter William Patoun and titled Advice on travel in Italy, the author gave advice to his countrymen who intended to set out on the Grand Tour to Italy, the journey that young people from the ruling classes across the continent undertook during their education to discover Europe and, in particular, Italy. “After taking possession of your accommodations,” Patoun wrote, "your next necessary piece of furniture is ... a cicerone. There are two young men in Rome at the moment who do this work, Messrs. Morison and Byres, both Scottish and both very good (the latter quality is not a consequence of the other). Morison is esteemed for being the best connoisseur of medallistics and classical art, Byres the friendliest and most communicative. Having esteemed both of them I cannot recommend one at the expense of another. The tip given to them by each gentleman is twenty zecchini for a course, thirty if there are two. It is unnecessary to mention Lorsignori who are treated with much consideration and who often have the honor of dining with all young men of rank who travel. Both are originally painters, and they certainly know both paintings and antiquities well."

The two figures mentioned by Patoun are two Scottish artists, Colin Morison (Deskfor, 1732 - 1809) and James Byres (Tonley, 1733 - 1817), who were born as artists, and from quite similar paths: in their twenties, both left Scotland to move to Rome in order to perfect their studies (Byres, who in addition to being a painter was also an architect, received an award from the Accademia di San Luca in 1762 for one of his projects). The two fell in love with Rome and became fine connoisseurs of it to the point that they decided to settle in the city and to combine their usual activities with that of tour guide: a profession that in the Italy of the time was indispensable for young Europeans who were on their Grand Tour, and which, above all, was very profitable, especially if it was combined with other activities. Both Morison and Byres, in fact, also successfully carried out the trade of antiquarians and art dealers.

Tour guides for the young Grand Tourists (known as “Cicerones”) were an invaluable support: at the time, of course, the ways of visiting were very different from those of today, and visiting, for example, a palace or collection required someone familiar with the local landowners and members of the elites. In addition, the cicerone could also act as an interpreter, eliminating language problems. And again, the tour guides knew local painters who could be hired to have a portrait-souvenir made, as well as merchants who sold precious objects that tourists could buy and take home with them: and since the guides were also connoisseurs of art, they could advise young tourists, especially those completely clueless on the subject, on what to buy. “Expert cicerones,” wrote scholar Arturo Tosi in his book Language and the Grand Tour, “were the main linguistic intermediaries between travelers and local communities. They were indispensable characters, always present in all cities that had an international reputation, often gifted with artistic and social skills. Their manifold experience was known to many foreign visitors, as were also their skills of insistence and manipulation that some travelers attributed to them.” Not all cicerones were in fact animated by... good feelings: in fact, travel reports of the time speak of guides who tried to swindle travelers, so relying on reliable figures was essential to avoid unpleasant surprises during the trip. This was also because not only knowledge of places, but also the purchase of goods often depended on the knowledge and honesty of the cicerone.

The use of the term “cicerone” to refer to tour guides, which, according to Bruno Migliorini, author of Storia della lingua italiana, even had seventeenth-century origins, finds its first attested use in the 1719 Dialogues on medals by British writer Joseph Addison, the “father of English journalism” and founder of the Spectator: “I was surprised,” the work reads, “to see my cicerones so familiar with the busts and statues of all the greats of antiquity.” Welsh painter Thomas Jones (Cefnllys, 1742 - 1803) defined the “cicerone” as “a person who accompanies foreigners to show and explain to them the various ancient and modern buildings, statues, paintings and other curiosities in and around the city.” This label fitted well with the figure of James Byres, defined by art historian Peter Davidson as a “crucial figure” who led a “virtuoso life.” Byres stayed in Rome for some 30 years (he arrived in 1758 and stayed there until 1790, taking up residence near the Spanish Steps, first in Strada Felice, today’s Via Sistina, and then moving in 1764 to Strada Paolina, today’s Via del Babuino): three decades during which he frequented artists, antiquarians and merchants and guided numerous tourists and art students to discover Rome, charging not a small fee, moreover (he was one of the most expensive ciceroni).

Scholar Paolo Coen has gathered interesting information on how Byres organized his courses, that is, his guided tours around Rome that nevertheless resembled real teachings, study courses in their own right among the antiquities and modernities that could be admired in 18th-century Rome. On the strength of an abundant clientele united by language (the Scotsman was one of the ciceroni of choice for English-speaking travelers, both those arriving from the British Isles and the few arriving from America), Byres used to assemble classes of six to twelve travelers, who followed a course of five or six weeks, and for which each traveler spent £10 a week (43 Roman scudi: a sum that corresponded, to give an idea, to slightly less than the monthly salary of a laborer in the factory at St. Peter’s, but keep in mind that the Grand Tourists came from the wealthy classes), a figure three times higher than what other cicerones, such as Colin Morison, were charging. Byres’ tours did not follow regular schedules: they were decided, for example, on the basis of weather conditions. On fine days, Byres would take his clients to visit outdoor antiquities, when the weather was bad the museums, while if the day was fine but windy they would go for churches or picture galleries. And of course, knowing the artists of the time, he was also able to introduce them to his wealthy clients: for example, we know that he also arranged appointments for posing sessions in the atelier of Pompeo Batoni (Lucca, 1708 - Rome, 1787), the great Lucchese painter who also made money by making portraits of Grand Tourists.

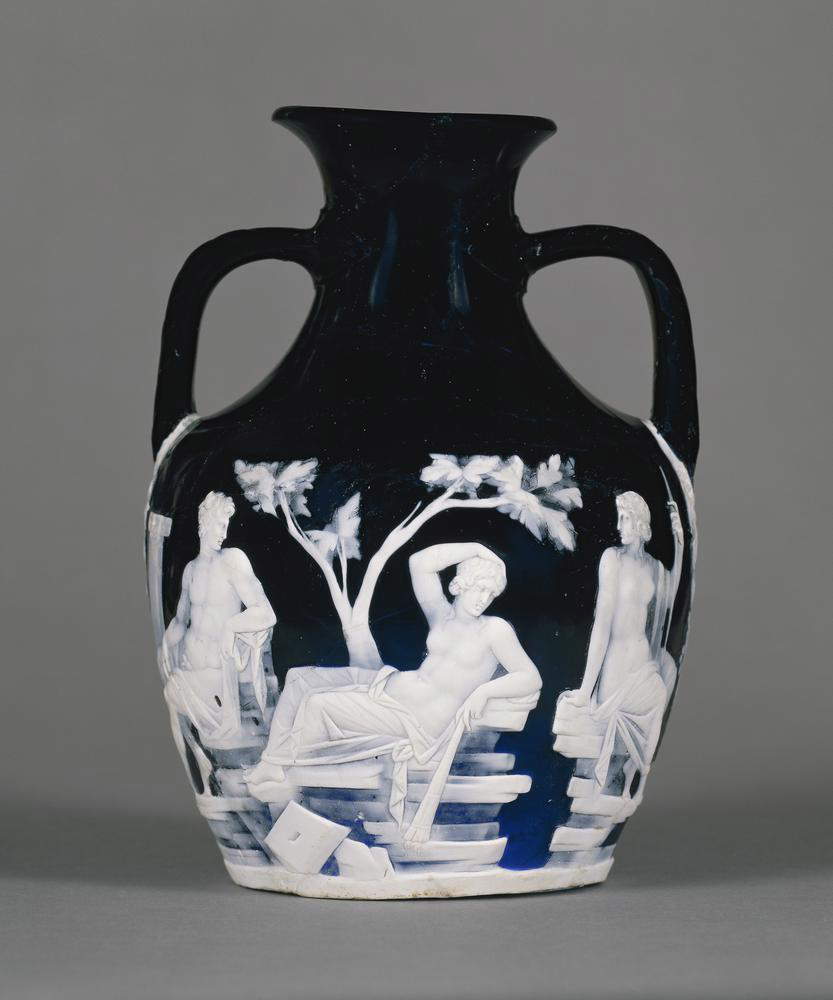

“Although lacking a solid and adequate course of study,” Coen writes, “in his early Roman years he tried to fill in the gaps through an extensive series of readings: the effort is reflected in the library, which although overlooking various disciplines-modern literature, history, geography, philosophy, economics, religion, music, chemistry, physics and other exact sciences-has its fulcrum precisely in the classics. Byres therefore soon earned a reputation as a man of culture, especially in the circuits associated with the Grand Tour.” Byres then also had interests as an archaeologist: by March 1766 he began an excavation activity at “Civita Turchino” (present-day Corneto Tarquinia) with the idea of compiling a History of Etruscans, more for pleasure than for profit. In addition to his profession as a tour guide, as mentioned above, Byres joined that of art dealer and agent (as for those of painter and architect, however, they were soon abandoned by him: as a painter he stopped at a young age, and his architectural projects remained only on paper). He was brokering business for wealthy English collectors, but also buying and selling objects in his own right, so much so that he went so far as to set up “a thriving and specialized business” (so Coen) that by 1790, the year of his return to Scotland, he had several partners and associates. Byres dealt in “classical and modern objects,” Coen writes, “without apparent solution of continuity, provided they were marked by high quality and economic standards. In the antiquarian field he worked with both minute artifacts and life-size marbles, as evidenced by the numerous licenses for England, where along with fireplaces, mugs, masks and busts several statues also stand out, including the two shipped in 1784, a full ten feet high.” Objects passed through his hands such as the Portland Vase now in the British Museum, a splendid glass vase from the first century A.D. that in the seventeenth century was one of the most excellent pieces in the Barberini collection, and was sold to Byres by Princess Cornelia Costanza Barberini, who gave it up to repay her gambling debts, or the Baptism of Christ by Nicolas Poussin now in the National Gallery in Washington, purchased by the Boccapaduli family.

A cicerone such as Byres was not only a guide, Cesare De Seta also recalled in his L’Italia nello specchio del Grand Tour, if anything “a true specialist [...] capable of choosing the most interesting litinerario, the culturally richest one and, by proven competence, [...] able to move in that great art market that is the Italy of the time.” The ciceroni therefore became a... typical element of the Italy of the time, so much so that they even entered view paintings. Tour guides are usually clearly distinguishable: they carry a conspicuous stick and most often are depicted in the act of pointing at something, as is the case in a painting by Bernardo Bellotto, Canaletto’s nephew, preserved at theAccademia Carrara in Bergamo, where a guide is seen caught in the act of explaining the Arch of Titus in Rome to one of his clients. In theInterior of the Temple of Poseidon at Paestum, a work by Antonio Joli kept at the Reggia di Caserta, we see instead, in the lower right, a group of gentlemen around a guide, in this case leaning on a staff, as he illustrates the ancient ruins to a small group of travelers dressed in elegant clothes, and arranged around him in a circle to listen.

The clothing used by the travelers was indeed that which was appropriate for wealthy gentlemen around Europe, who did not, however, want to give up comfort: in the paintings of the time we see Grand Tourists in fact wearing shirts open at the chest (a concession that was fine for travel but not in society, where instead one covered one’s neck with well-tied collars and elegant ties), short, nimble pants, and more practical jackets than those worn in the city. To get an idea of what a traveling party might have looked like, one can see a painting by the Austrian Martin Knoller (Steinach am Brenner, 1725 - Milan, 1804) preserved in the Ferdinandeum in Innsbruck: Count Charles Gotthard of Firmian in a group of friends on an archaeological excursion to Cumae, from 1758, which we can consider a sort of... group photo of the time, featuring Trentino diplomat Carlo Gottardo di Firmian, who was in his 40s at the time (such outings were in fact not the prerogative of young people: even established professionals on missions abroad allowed themselves outings like this one). It is a painting that, wrote art historian Fernando Mazzocca, we can consider “an emblematic image of the passion for antiquity and the fascination exerted on foreign travelers by the ruins that dominated the Italian landscape.” Firmian is the figure in the center, caught observing the relative and pointing to the book he holds in his right hand. Behind him, lying down and intent on drawing, we find the 30-year-old Knoller, who is self-reflecting. The figure beside Firmian, holding a cane, is most likely the leader of the group of friends. They are, Mazzocca writes, “all enraptured by the beauty of the place and the majesty of the ruins half-buried by vegetation.” These were the groups that wandered around in eighteenth-century Italy to discover its wonders, always accompanied by their guides. And, as many scholars have noted, it was also these journeys that formed Italy’s self-awareness.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.