At a time when madness was still seen as an obscure and stigmatized phenomenon, Théodore Géricault (Rouen, 1791-Paris, 1824) tackled the subject with rigor and depth. We are talking about the same Géricault who, yes, had led FrenchRomanticism by imposing himself with scenes of heroism and tragedy, but who in the same years had decided to explore completely different territory. After The Raft of the Medusa of 1819, a manifesto of human despair and a denunciation of the cruelty of fate, the artist abandoned the emotions of the Romantic period to turn his gaze to a quieter and more personal abyss, that of the human mind. His protagonists therefore are transformed: forget castaways and heroes. Instead, the main characters are forgotten individuals, locked up in asylums. Géricault thus produced works that go beyond the classical clinical representation. In the series of Portraits of the Insane, created between 1820 and 1821, the French artist combined observational rigor and human compassion. Ten faces of the mentally ill, portrayed from life, devoid of embellishment or pietism in fact render all the complexity of the human soul in its shadowy areas. Only five of the paintings have come down to us, but they are enough to understand the revolutionary scope of an endeavor that anticipates, by decades, modern sensitivity to the psyche and human frailty.

Long ignored, the portraits were rediscovered only in the 20th century. Lorenz Edwin Alfred Eitner, an art historian and director of the Stanford University Museum of Art, devoted a penetrating analysis to them in the volume Théodore Géricault published by Salander-O’Reilly in 1987, recognizing them as the transcendent achievement of the painter’s last years. For Eitner, the portraits of the alienated are studies executed quickly from life, born of an inner urgency rather than an academic intent. For this reason, the paintings cannot be considered and reasoned for the audience of the time. The intimate character, far from the heroic and monumental tones of Medusa, thus makes it one of the most intense cycles of the entire nineteenth century. According to his own testimony (a correspondence preserved in the Louvre archives dating from 1863, as Eitner reports), Géricault made these portraits upon his return from England, perhaps for Étienne-Jean Georget (1795-1828), an alienist physician (i.e., specializing in mental illness), his friend and a central figure in French psychiatry and head of the Salpêtrière (a hospital center founded by King Louis XIV in Paris). A pupil of the school founded by Philippe Pinel, Georget embodied the new science of the mind developed in France after the Revolution: a discipline that had removed the mentally ill from prison confinement, recognizing in them individuals to be understood and treated, no longer monsters or sinners.

After the doctor’s untimely death in 1828, the paintings were divided between two collectors and, as already anticipated, only five of them have survived. Today the works are kept in different museums: Alienate withmonomania of military command is in Winterthur (Zurich), at the Collection Oskar Reinhart “Am Römerholz”; Alienate withmonomania of theft is housed at the Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Ghent, Belgium;Alienate withmonomania of gambling, after a long and complex collecting affair, became part of the collections of the Louvre in Paris. In contrast, the painting Alienate withmonomania of envy is kept at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, while theAlienate withmonomania of child abduction is in the United States, at the Springfield Museum. In each face, Géricault thus captures the shadow of a monomania, that is, an obsession: a lost look or a strained smile. The artist’s eye does not judge or observe from above; instead, it participates in this case in the illness and shares it. It is as if Géricault recognized in the faces deformed by suffering the same vertigo that, in all likelihood, he himself had gone through coming back from depressive crises and a life marked by torment.

As anticipated, the cycle devoted to the Alienated was created by the artist after his return from England, although, of all the works, theAlienated with Monomania of Envy seems to have been painted at a stage prior to his English sojourn. In an 1863 letter, critic Louis Viardot says he accidentally discovered the faces, probably in Germany, calling them haunting. And again according to Viardot, the portraits would have been made between 1820 and 1824 (probably an inaccurate dating for Étienne-Jean Georget). In any case, there are no documents attesting to Georget’s specific interest in this type of depiction, unlike the more famous Esquirol, a reformer of psychiatric hospitals, who in 1818 claimed to have drawn over 200 mentally ill patients with the intention of publishing his observations.

“The study of the physiognomy of the insane is not a matter of vain curiosity,” Alfred Eitner reports in his text referring to the words spoken by Esquirol. “It helps to define the character of the ideas and emotions that fuel the madness of the mentally ill. For this purpose I have had drawings made of more than two hundred interned patients, and perhaps one day I will publish my observations on this interesting subject.”

It was indeed necessary to wait until 1924, or the centenary of Géricault’s death, to understand the historical importance of the portraits. In theAlienated with Monomania of Envy for example, the artist’s painting is deeply introspective. By eliminating painterly concessions, Géricault restores an actual clinical likeness of the sick woman, breaking with traditional portrait rules. His focus is on precise details. Indeed, we can observe the cap that covers her head, her clothing, her unusual expression, and her bulging eyes as elements that reveal the patient’s disorder and obsessive personality. Monomania, the systematic and obsessive mental illness described by Esquirol, thus became the meeting point for art and science. For the psychiatrist, madness reflected the anxieties of his time.

“Every revolution and collective passion,” Eitner writes, quoting Esquirol’s words again, “finds its mirror in the kindergartens of Charenton and Bicêtre.” Géricault, with his brushes, thus molded medical intuition into pictorial concept. Eitner also indicates how the series of the alienated made for Georget probably arose from a close collaboration between the artist and the doctor himself. Indeed, it is both a clinical and a poetic project. The doctor provided Géricault with access to patients and scientific context, but the painter went beyond documentation and revealed the drama and dignity of his models. The works, as Eitner reports, therefore place Géricault in the European avant-garde as powerfully as Medusa, yet remain obscure for a century.

The artist had always nurtured a deep interest in the world of medicine. Already during the making of the Raft of the Medusa, four years before the Cycle of the Alienated, he frequented the Beaujon Hospital, close to his studio, where he observed with morbid curiosity all the stages of suffering by studying the traces that illness imprinted on the human body. Inside the facility he had befriended a number of medical students from whom he received anatomical fragments that he arranged in still lifes and portrayed with almost scientific precision, as in the case of the painting Studies of Feet andHands made between 1817 and 1819 orAnatomical Parts of 1818-1819. The theme of madness, however, had a more personal significance for him. Indeed, mental illness was a real presence in his family; his maternal grandfather and an uncle had died in the grip of insanity, and Géricault himself, after the clamor of Medusa, experienced a period of deep depression accompanied by paranoid delusions. It is likely that just then he developed a new interest in medical research into the origin of madness. In those same years Henri Savigny, the surgeon who survived the shipwreck of the French frigate Medusa, was about to publish a study on the effects of hunger and thirst on the mental state of victims, and in all likelihood it was he who introduced Géricault to the nascent science of psychiatry. Shortly afterwards, when the artist was himself stricken by a crisis, he had the opportunity to experience directly the illness and the path to recovery: from that moment he began to observe with renewed attention, curiosity and participation the work of the alienists, including Georget.

The portraits of the madmen appear as half-figures, painted life-size, bathed in deep shadow from which only the faces emerge. At first glance they might look like ordinary bourgeois portraits were it not for the tension that runs through the features. Only theAlienated with gambling monomania looks at the viewer; all the others avert their eyes, lost in their own thoughts or unaware that they are being watched. Indeed, in each of them there is an inner turmoil that remains compressed behind the mask of the face. Géricault thus renounces theatricality and traditional representations of madness (the raving madmen, the possessed, the grotesque buffoons) to choose a direct and modern language. Unlike Francisco Goya, who 20 years earlier had depicted the madmen of the Saragossa asylum as a tribe in delirium, with theatrical gestures and imaginary scenarios, Géricault observes them up close, one by one, with the attention of a doctor and the pity of one who recognizes in them a part of himself. In The Asylum made between 1808-1812, Goya depicts alienated individuals involved in completely imaginary ceremonies or battles. In the painting we see one man with a feather crown offering his hand to be kissed, another, naked with a tricorn, simulates a gunshot, and a third (right) wears a scapular. Light enters through a single barred window and illuminates the gloomy stone space. Goya himself wrote to the politician Bernardo de Iriarte, “This is how I saw them in Zaragoza.” The work was taken up in an 1885 print, designed and engraved by José María Galván, with text by Juan de Dios de la Rada, to spread the most unique images of the San Fernando Academy.

In fact, Goya had already addressed the theme of madness with The Courtyard of Madmen, an oil on tin-plated iron work from 1794. In an open courtyard, identifiable with the ward of the insane at the Hospital of Nuestra Señora de Gracia in Zaragoza, the artist depicts a group of mentally ill people. In the center of the scene, two nude figures face each other like Greco-Roman wrestlers, evoking models from classical sculpture, while a janitor strikes them with a whip. Around them, however, other patients wrapped in threadbare white tunics that, as the Fundación Goya en Aragón portal reports, Goya defines in a letter as “sacks,” incite the confrontation. On the left, a man standing with his arms folded stares at the viewer with an expression of terror; on the right, a seated figure wearing a hat assumes a sarcastic grimace. Farther still, facing the wall, appears a standing figure wearing green and brown livery, the uniform reserved for patients considered less dangerous. The light that invests the upper part of the scene and that which enters through the grated window at the bottom of the painting soften the contours of the figures, unifying the space and erasing the angle at which the courtyard walls join. The dark and undefined environment here becomes a metaphor for the condition of the mentally ill and alludes to the darkness of their limited capacity for understanding and reasoning.

Unlike Goya’s works, then, Géricault’s portraits are depictions of real people, executed with a lucidity that includes emotion. The painter records the visible signs of illness through posture, the tensing of the mouth, as carefully as a doctor notes symptoms. His precision thus stems fromempathy. Géricault paints with the goal of staying true to the evidence before him, seeking truth and not dramatization. In those years, psychiatry was beginning to recognize madness as a natural process, readable through physical and behavioral signs. The outward appearance therefore became a precise key to understanding the inner state of man. As already anticipated in his severed heads and anatomical fragments painted years earlier, the artist had indeed shown that he could deal with painful themes with apparent coolness and inner intensity. Even in the portraits of the insane, scientific coldness coexists with restrained emotion: the result is a series of works of terrible beauty.

In the same years John Constable was studying clouds with similar scientific attention, trying to grasp the invisible laws that governed them. Both, each in their own sphere, thus molded observation into revelation: Constable with the sky, Géricault with the human mind. This is the moment when art and science met and shared the same belief in the eye as an instrument of truth.

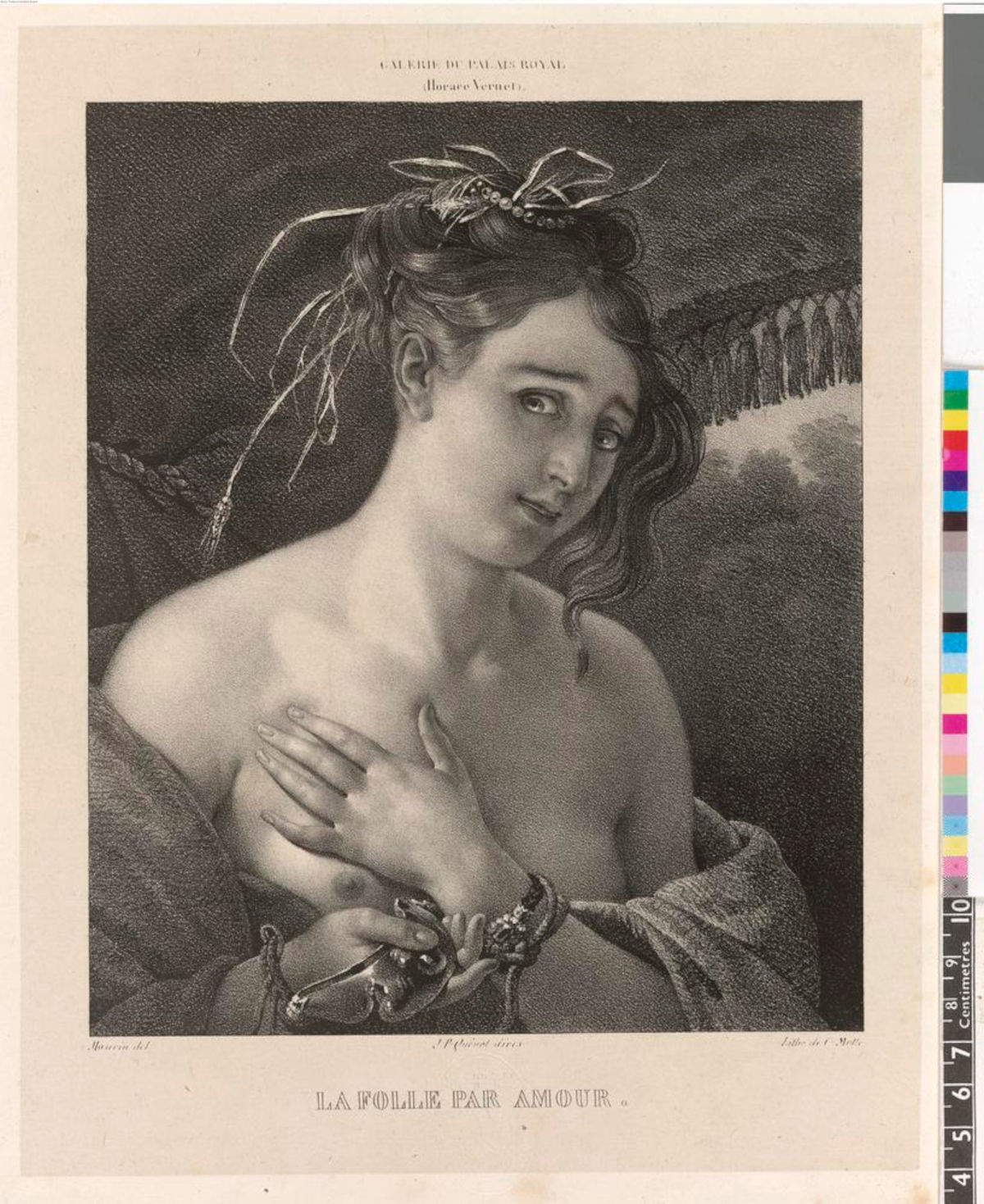

Other Romantic artists attempted to depict madness, but none reached the intensity of Géricault. Between 1825 and 1829 Horace Vernet created The Madwoman of Love, a young woman depicted in a half-length pose, with her hair up and adorned with a row of pearls and an ear of corn. Her chest remains uncovered, while her wrists, bound by a rope, accentuate the sense of bewilderment and passion that runs through the image. The work is a lithograph on chine collé, a technique employed in conjunction with printing processes such as etching or lithography to achieve finer details and more delicate surfaces.

Unlike the madness interpreted by Vernet, Géricault does not seek catharsis. His strength lies in theabsence of rhetoric. The five portraits of the alienated seem to be painted on the spot, in a few sittings and without preparatory drawings. Géricault worked from life, and like a landscape painter under the changing light of the sky, he captures the nuances of the mind in real time. The canvases show confidence, a firm and fluid brushstroke, devoid of second thoughts. It is as if painting, freed from heroism and myth, bends over man in his most fragile truth. “The face becomes the theater in which the soul exposes itself,” Lorenz Edwin Alfred Eitner again reports in his volume. And perhaps right there, in the light that separates the face from the shadow, lies the deepest point of Géricault’s art: the very shipwreck of the human being.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.