The former Slaughterhouse in Rome is an extraordinarily interesting space. First of all, for its history, which has its roots in the ancient (and lost) bet of a capital also industrial, of which today almost only vestiges remain: the Gazometro, the Centrale Elettrica Montemartini, the Mercati Generali and precisely also the immense logistics management and meat slaughtering plant. All of these spaces were sooner or later reconverted, regenerated, redeveloped-as is too easily said today-to new and tendentially more reassuring uses.

The Testaccio/Ostiense quadrant is in this sense one of the most lively in the city, precisely because of its post-industrial vocation that makes it a rare free space, almost in search of an author, in an urban context that has always been overwhelmed by universal meanings, and where it is therefore difficult for a truly contemporary sense to find citizenship. It tries, on the other side of Rome, the Flaminio, where large infrastructures for art and culture insist, such as the MAXXI and the Auditorium, which, however, in that case seem a bit like spaceships lowered from above, dialoguing little with a rather static neighborhood. The truly unique element of Testaccio/Ostiense is that the process of architectural reconversion is also associated with the enhancement of a truly creative social fabric: the young population of the university hub, the many communication agencies, the presence of clubs and places of aggregation, co-creation, and productive conviviality that enliven the neighborhood until late in the evening.

The other reason why the Slaughterhouse area is of great interest is precisely because of the ambivalence of its entire recent history. The cultural vocation has in fact emerged on two distinct tracks: on the one hand, the institutions’ desire to make it a Museum site (at first it was to be the second site of the troubled MACRO, over time it became a Center for Performing Arts, soon even a “City of the Arts” somewhat uneven and incremental); on the other hand, the ability to spontaneously dialogue with the city, which timidly - but with increasing conviction - began to inhabit it: transforming it into a public space in direct connection with the adjacent Testaccio Market, the only one of Rome’s markets with a marked aggregative attitude, and with the pavilions intended for the University of Architecture. In the meantime, other social and cultural realities “born from below” and of undoubted importance had consolidated within it, such as the Popular School of Music and the Global Village, or which had already been the result of even far-sighted public planning, but which was only partly able to respect the premises and promises, such as the City of the Other Economy.

On the whole, no one in all these years ever questioned that the Former Slaughterhouse had become, and would always remain, a public space. A place where, if you want, you can spend an afternoon of social and cultural initiatives, including exhibitions, without ever breaking a ticket. Where you can take children to play or stroll in a large pedestrian area, and let them discover a different way, not necessarily intermediated by commercial functions, of experiencing the city. Where you can prepare for an exam in an all-day study hall, or dine at the Testaccio Gastronomic Collective, participate in festivals like the Green Market Festival, or the many other initiatives that enliven indoor and outdoor spaces, especially on weekends.

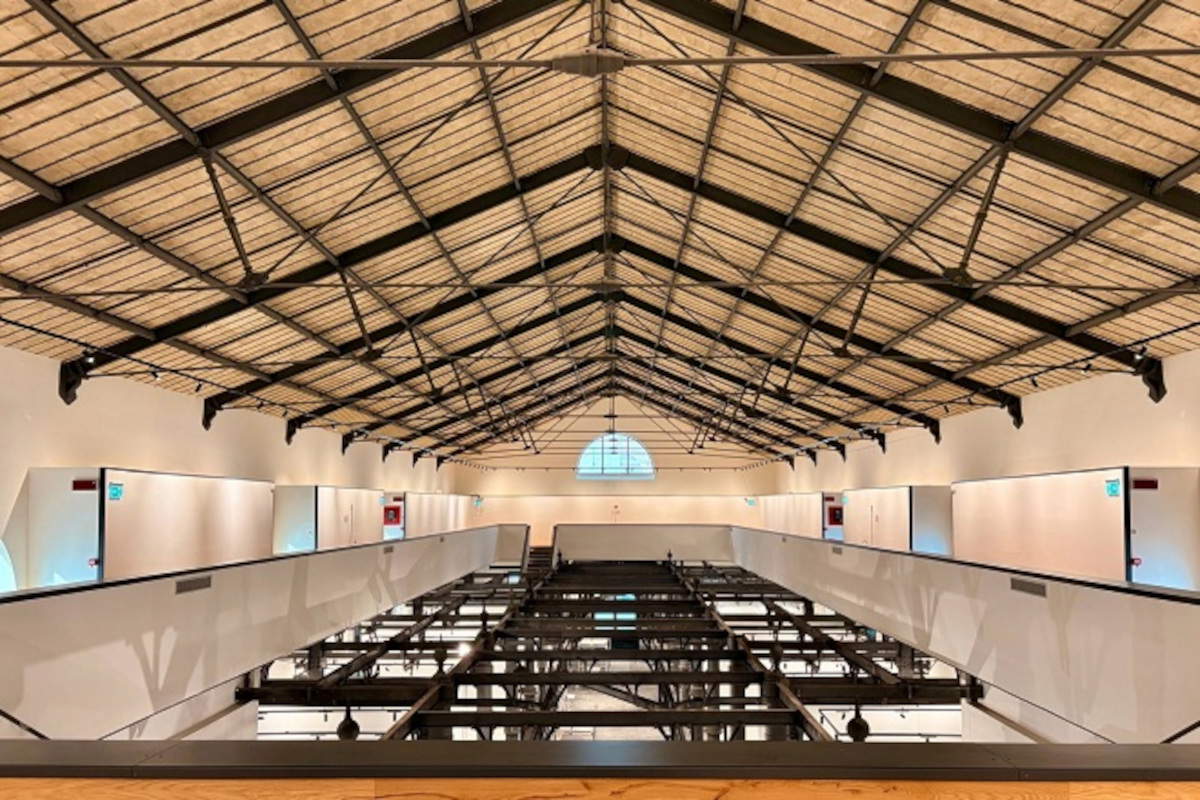

Today, the situation is not so clear. Testifying to this is the recent inauguration, in a new pavilion of the Slaughterhouse, of the Center of Photography, destined (I read from the press release) to be “the reference point for the promotion of contemporary Italian and international photographic culture.” On a first visit, it would even seem to be a more than commendable initiative: an architecturally brilliant recovery of the old slaughterhouse, 1,500 square meters capable of hosting several exhibitions and events at once, a management that seems to convey a certain decorum, good - though inevitably compromising - functionality and the undoubted professionalism of the fitters and the hall staff.

But the message reaching the citizenry is counterintuitive. If in fact, in this case more than legitimately given the presence of as many as three inaugural exhibitions, admission costs 10 euros and there is no convention, how can one justify the coexistence within the same complex with other exhibition spaces that, by a well-established policy choice, are instead all free?

A few meters away, we remind you, there are two exhibitions going on in the other pavilions where you do not pay a euro. At Hall 9B the exhibition for the 50th anniversary of “Republic” has been raging for days. And while it makes a bit of an impression of “The U.S. Air Force presents the beauties of Hiroshima in the 1930s,” it must also be said that it offers an interesting itinerary and a lively public program of meetings and reflections on the Scalfarian epic and Italy at the turn of the millennium. An evocative journey through the work of such a visually striking artist as Gianfranco Notargiacomo is set up at 9A. Other exhibitions, meetings and events, presumably free of charge, will take place at the Pelanda and other adjacent spaces. So many of us are now asking: why the sudden rupture? What does it mean, in perspective, for the city’s “culture system,” with its network of civic museums, libraries, and initiatives in public space? Should we read it only as a contradictory signal or the beginning of a worrying reversal?

Knowing and studying for years the logics that govern culture in this city, nothing removes from my mind that all this has to do with the substantial opacity surrounding the birth of the new Slaughterhouse Foundation, from which it is hard not to expect that it will begin to nibble away, with the interests it may bring to bear, at the great public space of the Former Slaughterhouse. And that would be a big, dangerous precedent for the cultural life of this city. The Foundation, established last year as a nonprofit entity, with “first founding” members limited to Roma Capitale (so, to be clear, us) and the University of Roma Tre, is open to other future members, subject to the approval of the first two. But it is unclear, to begin with, how this will improve engagement with existing cultural entities, such as the Academy of Fine Arts (ABA), excluded against its will from the corporate structure. Even more opaque, going forward, appears the picture of internal choices and dynamics, especially at such a delicate stage of resources, investments and cultural programming.

Meanwhile, the Center of Photography, almost a stone thrown against the pre-existing environment, defines itself on the home page of the website, perhaps the result of an intense brainstorming session, as “Public” (!), the “First” (heaven forbid), but above all “New.” The New Moving Forward.

The author of this article: Antonio Pavolini

Antonio Pavolini è un analista dell’industria dei media, esperto di transizione digitale e nuovi modelli di business. Collabora con università e centri di ricerca internazionali. Ha pubblicato diversi saggi, tra cui Oltre il Rumore (2016), Unframing (2020) e Stiamo sprecando Internet (2023), che trattano del rapporto tra media tradizionali, internet e spazio pubblico digitale. Insegna presso la NABA di Roma, occupandosi di teoria e sociologia dei media.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.