According to the Buddhist view, the fundamental law of the universe finds its manifestation in every single living being. “All life forms,” says Daisaku Ikeda, who is among the most influential Buddhist masters of our time, “are not isolated elements, but are integrated into the cosmic life force. Put another way, the part is the whole and the whole is the part. Human beings and nonhuman nature are integral parts of the same cosmic life force. They are unique in their individual characteristics and a whole from the standpoint of symbiosis. They are inextricably interrelated.” The echoes of Eastern philosophies and spirituality reverberate in the pictorial production of Matteo Pannocchia, a young Leghorn artist who has matured a vision, a recognizability and an awareness of his own means at the age of 30, at the culmination of an erratic and tortuous path, devoted to experimentation, yet consistent in its apparent lack of any linearity. Pannocchia, born in 1990, trained at the Art Institute of Pisa studying graphic design and later came to painting, then set it aside, returned to it, deepened it by studying at theAcademy of Fine Arts in Carrara first and then in Bologna, then goes back to doing something else, decides to develop in parallel open projects on completely different fronts (he is also a musician, and with his alter ego De Skape Studio produces beats that draw from hip hop, soul, ambient music: needless to remark that his songs seem to be the translations into notes of his paintings). The flame of painting, however, continues to burn. It cannot be tamed, it cannot be extinguished. This is what happens to every true painter. And for at least the past two or three years the Leghorn artist has been experiencing a period of copious, brilliant productivity.

Matteo Pannocchia traces the origins of his painting back to Notorious B.I.G.: rap music has always been among his listeners, so he chose to dedicate the first painting of his career to one of the most relevant rappers in history, to the master of the East Coast hip-hop scene of the 1990s, who died murdered at the age of twenty-seven yet to be. The small canvas from which it all started is still in Cob’s studio, somewhat hidden: it is a portrait based on what is perhaps Notorious B.I.G.’s most famous photograph, the shot of Barron Claiborne that captures him from the front, a few months before he died, his gaze grim but dull, the gold chain around his neck, on his head the crown placed “on his twenty-three,” as one would have said a few decades ago. Pannocchia softens the photographic tones, cleans, fades, dilutes everything by spreading over the rapper’s image an opaque patina that makes him appear to us at once more human and more distant, a kind of ghost. This is Matteo Pannocchia’s first declared work, a rehearsal, a test, perhaps executed without even thinking too much about it: and yet one can already glimpse in nuce the evolution of his painting which is made of opaque and muted tones, of evanescent and nebulous compositions, of loose and light signs, almost graphic signs (Pannocchia’s painting, it should be emphasized, is supported by an abundant graphic production, the paintings often arise from drawings, even quite elaborate ones: the young Tuscan artist brings with him the whole tradition of his home region).

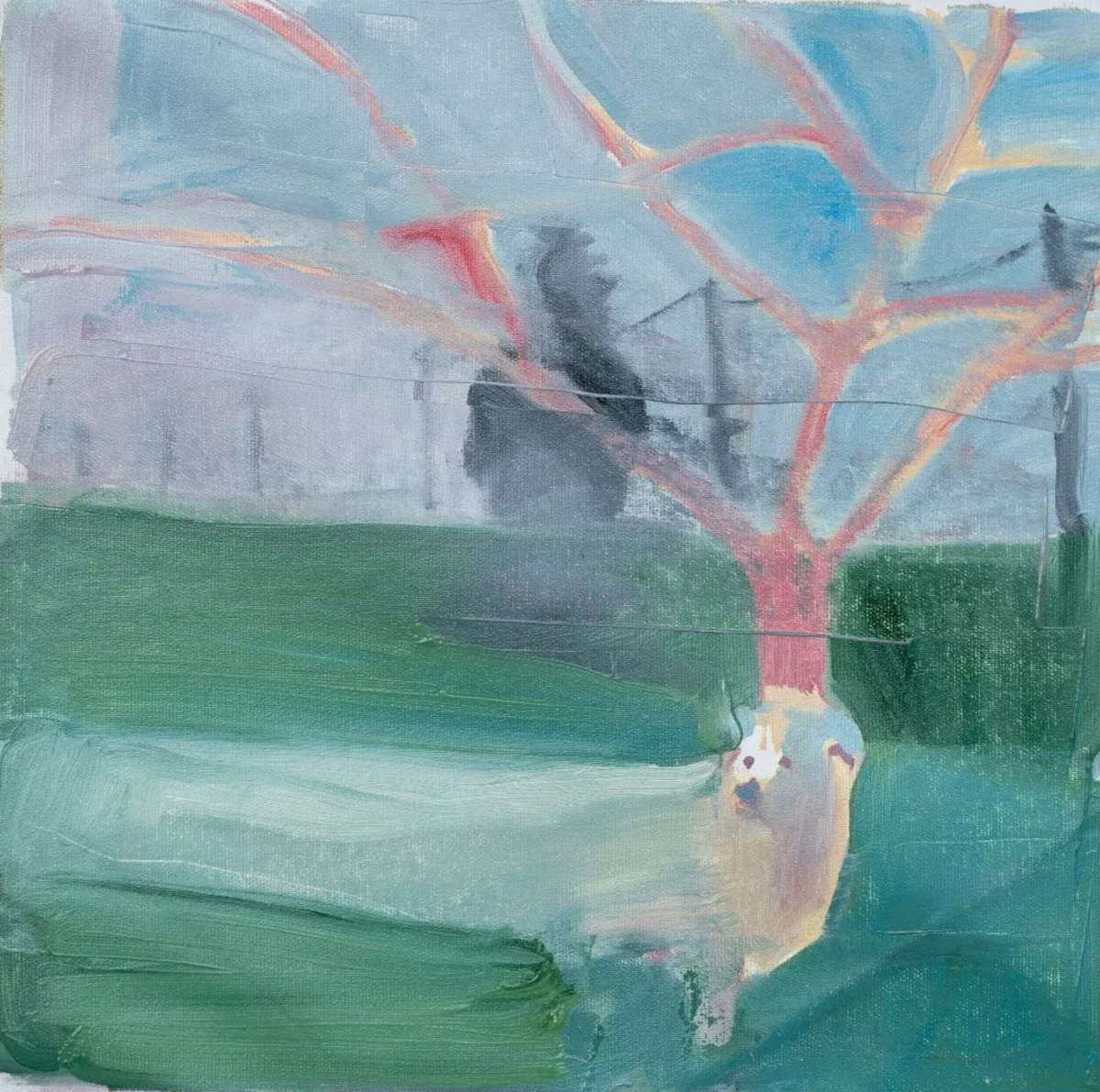

From there on it was a continuous experimenting before arriving at what is now his painting, an oil painting obtained with slow work rhythms: it might seem a contradiction to an art that seems instead instinctive and gestural, but without slowness Matteo Pannocchia’s paintings would not exist. “Slowness,” he explains, “I understand it as rhythm and process. Not ’slow’ in the sense of being closed in one’s comfort zone: in my personal experience, it is a growth, being patient and following one’s own path.” He adds a phrase he jotted down on his cell phone, “Sowing and watering, for better or worse then something comes up.” In his case, the harvest began some time ago to bestow rubicund, ripe fruit. One can take as an example, among the first signs of this coming of age, a painting entitled Better to stay outside: a seemingly mundane scene, a girl sitting in the garden of her house, the dog on the grass striding toward the building in the background, a tree beyond the neighbors’ fence, appears imbued with all the restlessness that lies behind the most resigned everyday. The girl’s gaze is lost in the void, the garden looks like an acid lake, the sky is tinged with purple, the house has unreal proportions, the tree has the appearance of a skeleton. Pannocchia intervenes in shapes and colors to convey to the viewer that sense of alienation that is peculiar to his, to our generation. At times there is also an air of suspension that seems to come from a profound reflection on certain American art ranging from Edward Hopper to Richard Diebenkorn: Don’t worry too much is perhaps the painting that comes closest to Hopperian imagery, with that bare and humble room where the girl and the dog return, and where an undefined opening lets in a golden, unreal, metaphysical light. On the surface of the canvas mingle concrete images, memories, motifs that come from the artist’s unconscious, for whom painting, he tells me, is also a kind of self-analysis, an introspective investigation: it is also for this reason that his toolbox seems to recall more the dimension of dream and memory than that of reality.

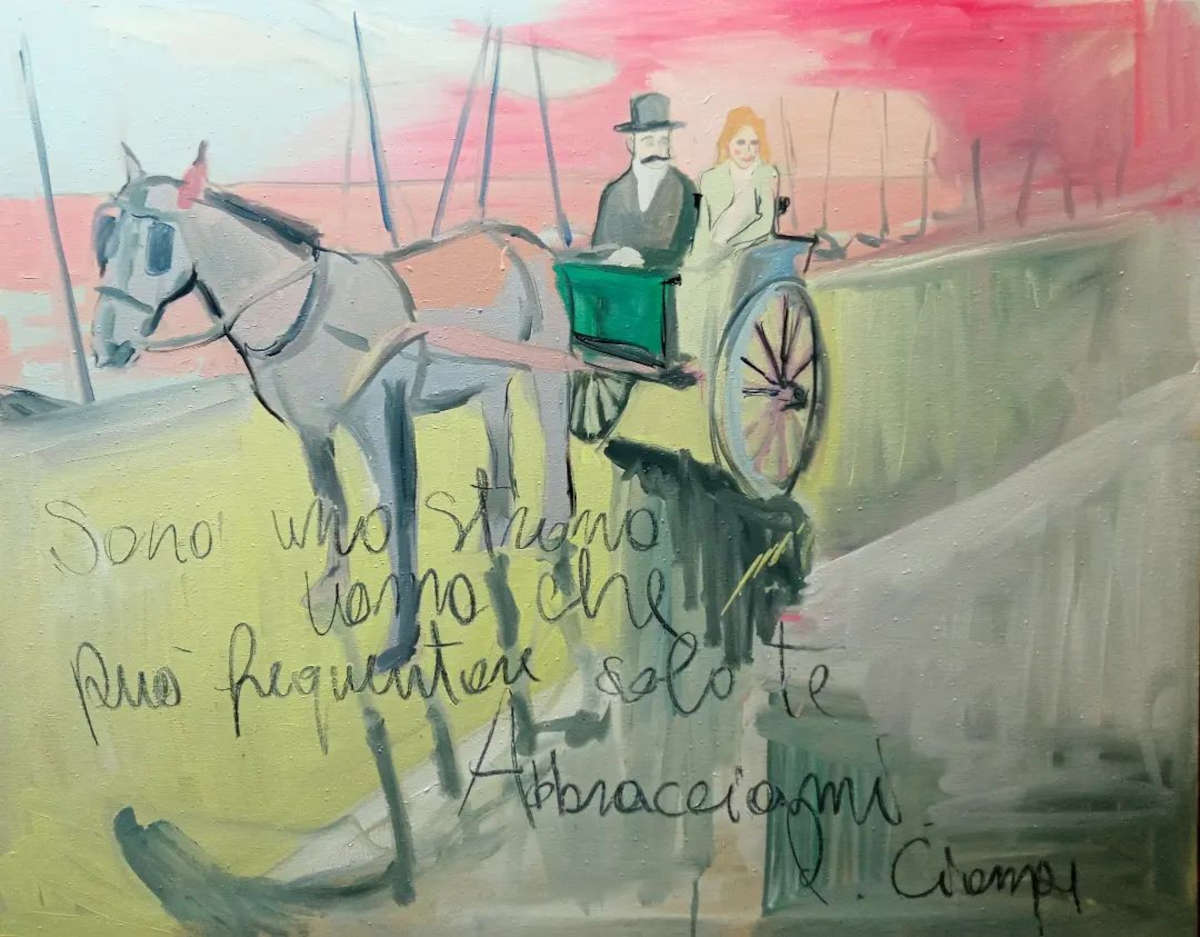

There is, however, no thoughtful research on subjects in Matteo Pannocchia’s painting. The Leghorn artist lets himself be guided by the inspiration of the moment. It can be an instant of the everyday, it can be a memory, it can be a video watched on Instagram or YouTube, it can even be a song. The departure, however, is almost always the drawing. The arrival is a scene that is grounded in a strong sense of the figure and a solid and thoughtful compositional framework, and yet seeks a mediation between figuration and abstraction, while leaning toward the former and while almost always taking on the appearance of mirage, memory, hallucination. The result is achieved through rigorous work on color and form. The colors are cold, delicate, impalpable, always unrealistic. And to the forms Pannocchia applies a process of constant subtraction and flattening: the result is figures that verge on the two-dimensionality of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, his other reference, often also for the strongly foreshortened, oblique shots. “Matteo prepares his particular narrative in images,” wrote Jacopo Suggi, “relying on photographic cuts and framing, and a peculiar palette made of clear, misty colors, sometimes usually by single figures, made even more solitary by apurging of details, subtracting everything not deemed necessary to convey a message, vindicating the painter’s desire to entrust the public with works of great immediacy and intelligibility, a meaning also often reinforced by the presence of inscriptions and slogans.” It may happen, moreover, that the source that inspired the painting is made explicit: not infrequently Pannocchia fills his paintings with phrases from literature, cinema, and music. “I am a strange man, who can hang out only with you, embrace me”: the verse of a Piero Ciampi song covers the light, ethereal, incorporeal image of a buggy on which a couple of lovers sits and which is pulled by a horse: the scene of yesteryear transports the viewer to the seafront of an early 20th-century Livorno that seems to have come straight out of a painting by Guglielmo Micheli or Renato Natali, bathed in the acid pink of a sunset that often returns in Pannocchia’s work. A pink that derives from the lesson of Philip Guston and that the Leghorn artist has made his own with the aim of giving lightness to his paintings. It is after all the search for lightness that is one of the main concerns of his art. Somewhat by practical calculation: we are still talking about an object that a person puts in the house, he tells me. And it is not easy to find an artist who is willing to consider the product of his talent also for what it will be for those who will buy it: a piece of furniture. And since few people want to hang an oppressive painting on their wall, it’s better to stay light. But the lightness that Pannocchia seeks is also a reflection of his understanding of life. It is not a “superficial perception of life,” he explains, “but rather it is a consequence of personal inner work. It is a confident and optimistic way of living, a kind of awareness of one’s own value and potential and that everything, even in the most difficult moments of life, can be transformed into something positive.” “Lightness” is perhaps the most recurring noun as he shows me the paintings in his studio, a small backroom open to the street that looks a bit like a miniature gallery and a bit like a pied-à-terre, in the middle of Jewish Livorno, just behind the Royal Ditch into which legend has it Modigliani hurled his own heads, in the heart of ’a neighborhood that has always been frequented by artists for the last two hundred years, an area of the city where that lightness seems to be felt in the noises of the streets, to be seen in the people, to be breathed in the wind, to be experienced even on oneself even if one has never been around here before, because this is how one lives here. Slowly. With that fresh, young and even a little melancholy lightness that Giorgio Caproni, far from his Livorno, tried to retrieve away from home in Versi livornesi, the lightness he tried to evoke, toward which he wanted to return (“My hand, make yourself feather: / make yourself sail; and light / moving on the keyboard, / be cautious. And take care, before / you stop the rhyme, / that you are writing of one / who was alive and was true. // You know that my prayer / is blunt, and that error / is ready to turn the heart away. / Be witty and careful: pious. / Be lean and be poetry / if you want to be life. / And if you don’t want to betray / her simple glory, / be fine and popular / as she was - be bold / and trepid, all history / gentle, without ambition.”)

There are works, in Matteo Pannocchia’s production, that seem to evoke this sense of lightness more immediately than others, partly because of the recourse to an unfinished that is present in almost all of his recent works. For example, Close to the sea, a sort of self-portrait in a club on the Livorno waterfront. His city, the city that just this summer by popular vote voted him best artist in an impromptu event organized in Piazza Garibaldi, which gathered several young artists from the area. Or certain paintings set on beaches that evoke a little Tuscany, a little California (although the palm trees, we can be sure, are not those on Ocean Boulevard in Long Beach, but are those on Livorno’s Viale Italia, in the area of Terrazza Mascagni). And then swimming pools, tennis courts, tree-lined boulevards, domestic interiors, water parks, the image of a dreamy and nuanced contemporary Livorno. Matteo Pannocchia’s is also an existential lightness, a way of responding to the anxiety of everyday life, to the typical anxiety of a generation, those born between the 1980s and 1990s, which has faced economic crises, real estate crises, a pandemic, the mass media revolution, the resurgence of war scenarios in the middle of Europe, the of war in the midst of Europe, the collapse of the value system that had been built in the postwar period, which fell upon the young people who have now become thirty years old and who like no other generation before and after them have experienced such strong changes, so radical, so unpredictable, at such a sustained speed. An American journalist, Michael Hobbes, in a longform published in the Huffington Post in 2023, animated by graphics that echo the style of early video games, wrote in that millennials today are “facing the scariest financial future of any generation since the Great Depression”: a generation that feels cornered, overwhelmed, almost annihilated. In a word: that feels screwed. Lightness then becomes a necessity.

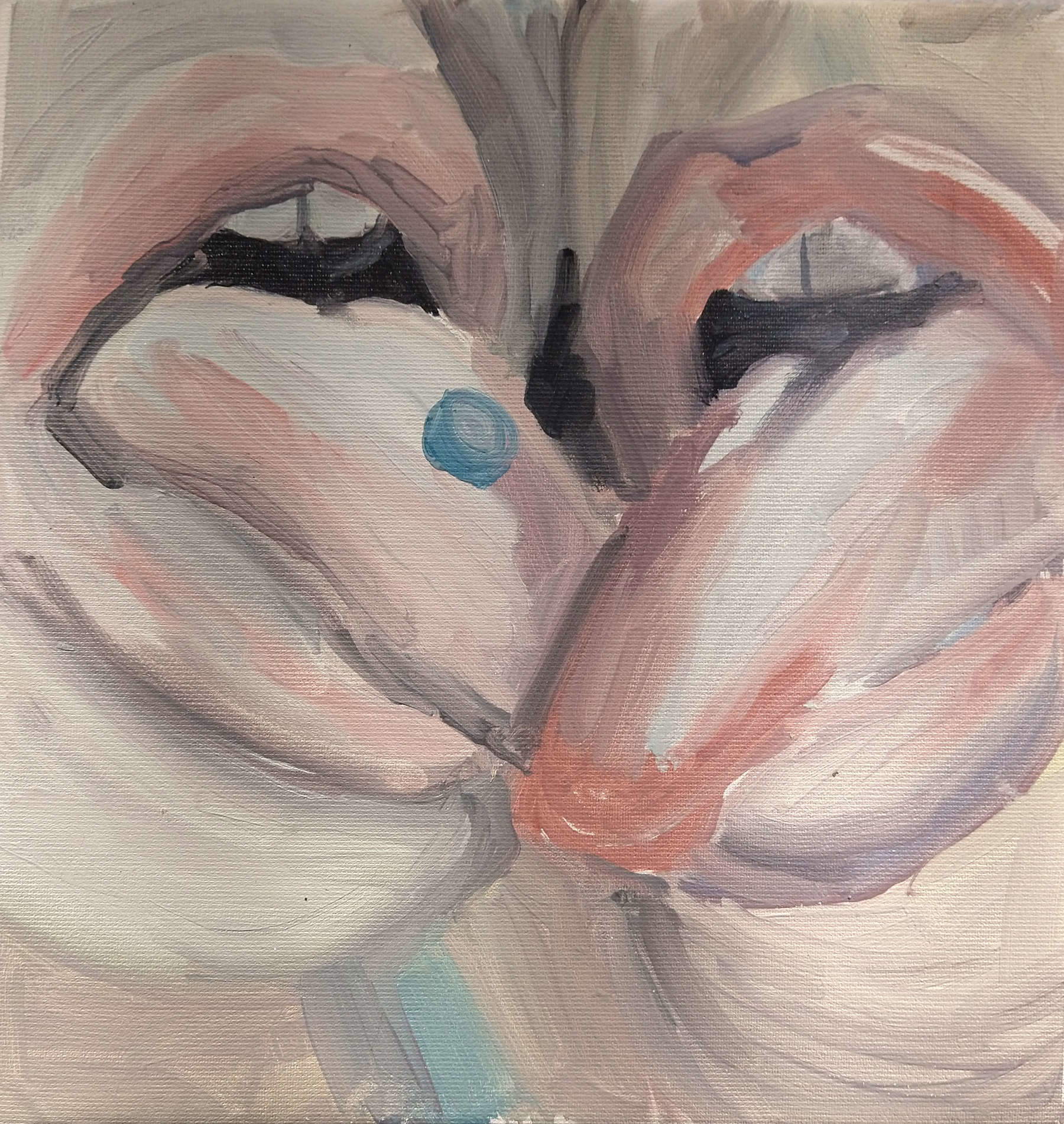

Hanging on a wall of Matteo Pannocchia’s studio is a recent painting, Early Morning, depicting a boy lying on a bed together with his dog, with a strong and bold foreshortening, a kind of Mantegna’s Dead Christ upside down, seen from the head. At the back, the room opens to an exterior, to a projection where a soldier with a trumpet is seen (a “brigadier,” the artist calls him). Pannocchia cannot quite explain what this painting means, but it is not important: an artist is not required to give explanations of his work. And whoever from an artist wants an explanation is not trying to understand, to read what is in front of him, to interpret it, but simply wants to be told a story. What is certain is that Pannocchia intends it as a work about disobedience, but the war theme has little to do with it: we could read it as a disobedience to any call to arms, to any expectation. A desire to be the only one to dispose of one’s life as one sees fit. Perhaps “finding a communion with animals,” as Jacopo Suggi noted in his paper that accompanied the Arterie exhibition in which Matteo Pannocchia exhibited his work in 2023 at the Extra Factory gallery in Livorno.

So we return to where we started: this lightness, in Matteo Pannocchia’s art, does not only involve human beings, it is lightness that animates a flow of energy. The dog, sometimes a concrete presence, sometimes a more immaterial, mystical, spiritual one (as it seems to be the one in Stretched dog, it is the dog the artist had as a child, he tells me, and thus returns to manifest itself in a recent work after a memory), seems almost to elevate itself to an animal symbol of this life force that manifests itself in all living beings. If a society has lost its points of reference, if a generation is left with nothing in which to recognize itself, then for Matteo Pannocchia the way to rebuild a relationship with oneself and with everything around can be nothing other than a return to nature, to a’primal energy, to a state of total lightness of mind, to a form of liberation that is substantiated by a return to a conscious and full simplicity, toward which to strive with a deep reflection on oneself, which may or may not be mediated by recourse to some philosophical or spiritual discipline. There seems to emerge, beyond the surface of many of Matteo Pannocchia’s paintings, a climate, a temperature bordering on mysticism.

“I believe in our being ordinary people,” he tells me as he talks about the Shortcut, a nostalgic painting, a snapshot of a car driving down a back road, a provincial road, at sunset, under a pink sky, over a pink road, the pink we now associate with the memory of the 1980s for who knows what reason, since there wasn’t all this abundance of pink back then (perhaps because of neon, perhaps because of clothing colors, perhaps because of early video games that only sent images in cyan and magenta, perhaps because of the hues that faded postcards take on). It is a painting in which we seem to read a kind of summary of Matteo Pannocchia’s still young career: a path that, in spite of the painting’s name, has nothing straight, linear, quick about it. Far from it: it is a sinuous itinerary, full of curves, to be traveled, however, slowly and with an awareness of the journey. Observing the landscape. Understanding that often to get to the destination there are no highways. Thinking, yes, about the destination, but with the knowledge that then once you arrive you might have to start again, because you find that the itinerary is not yet finished.

And today, having arrived at a rather well-defined artistic maturity, Matteo Pannocchia can be safely compared to that new young Italian figuration that brings together a heterogeneous nucleus of artists born between the 1980s and 1990s (we can include, just by way of example, painters such asexample, painters such as Francesca Banchelli, Romina Bassu, Fabrizio Cotognini, Rudy Cremonini, Alice Faloretti, Andrea Fontanari, Patrizio Di Massimo, Diego Gualandris, Davide Serpetti) capable of moving between reality and dream, between impression and expression, painters who often look to America (sometimes perhaps even too much) understanding, however, that remaining tied to the tradition of our country is the only way to emerge, artists who are opening (indeed, it can be said that they have already opened) a new, important, fruitful season for Italian painting. Some of them already have well-established careers, have already exhibited in national and international contexts, while others have only just begun to make their mark; it is a movement to be supported and encouraged. Certainly, for Matteo Pannocchia that slow, uncertain and full of curves journey that emerges from his paintings has only just begun.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.