Perhaps talking about the restoration of a painting these days for some might be out of place and inappropriate given the much more important things the country is dealing with, but if we reflect on it for a moment a similarity with our “waiting these days” we can definitely find it: in this case it is a magnificent seventeenth-century painting, perhaps even by Caravaggio, which in faraway Odessa in Ukraine is waiting to return to its own life. Suspended in its main function, that of being displayed and being admired closely by its audience, being able to witness the mastery and ingenuity of its author, teaching and describing that world it represented, somehow we find the same condition of suspension that we are experiencing these days. Without being able to see except at a distance, without being able to teach or learn with our schools and universities necessarily closed, suspended as well in so many of our fundamental prerogatives of confrontation, with at most the possibility of surrogating all this in a more or less real way through the use of electronic tools (and in this sense in these hours initiatives on the web or through the media of virtual visits to archaeological sites or entire art galleries are flourishing). But somehow these kinds of certainly laudable initiatives could, for some, exacerbate this feeling of endless suspension.

|

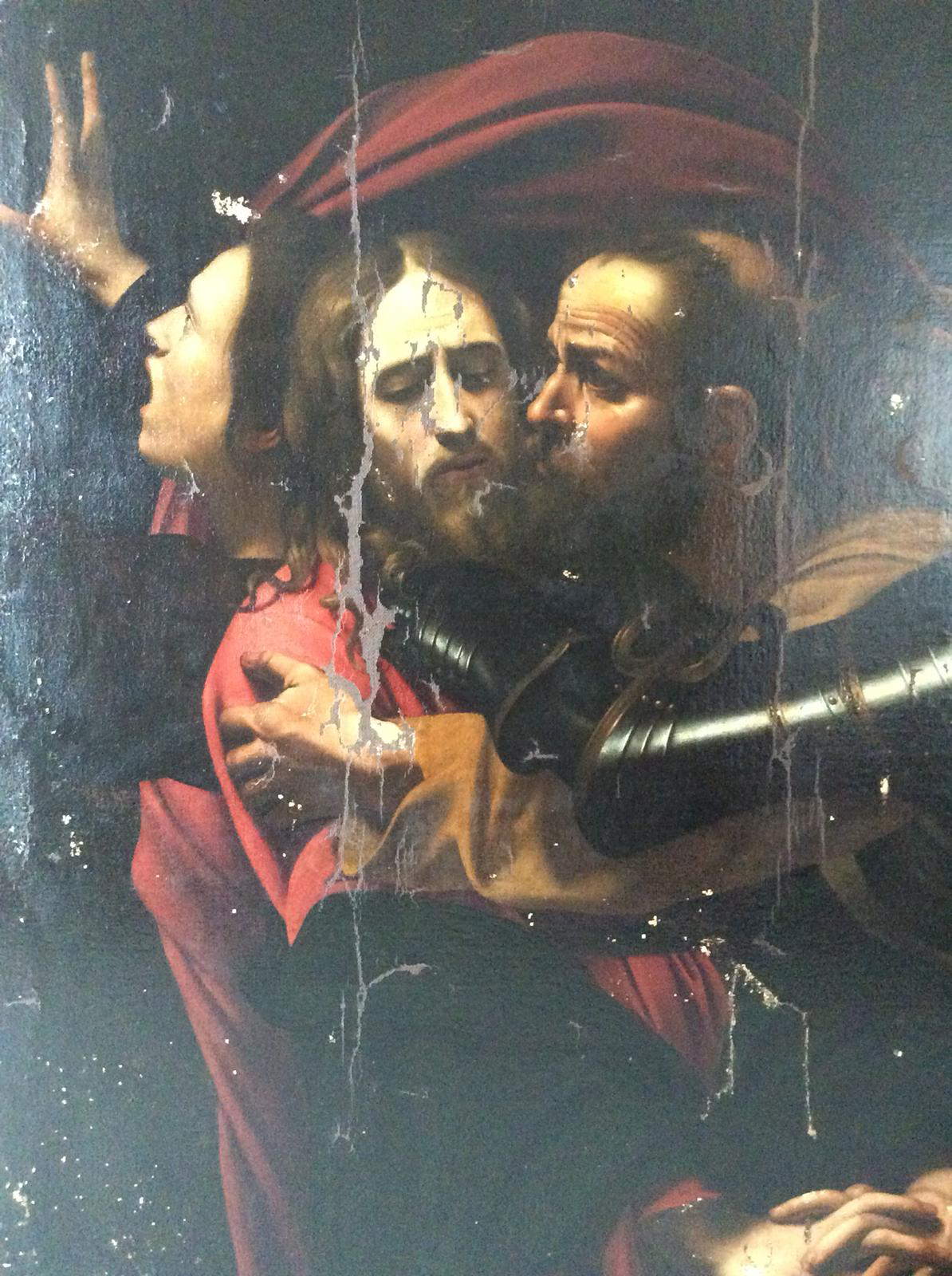

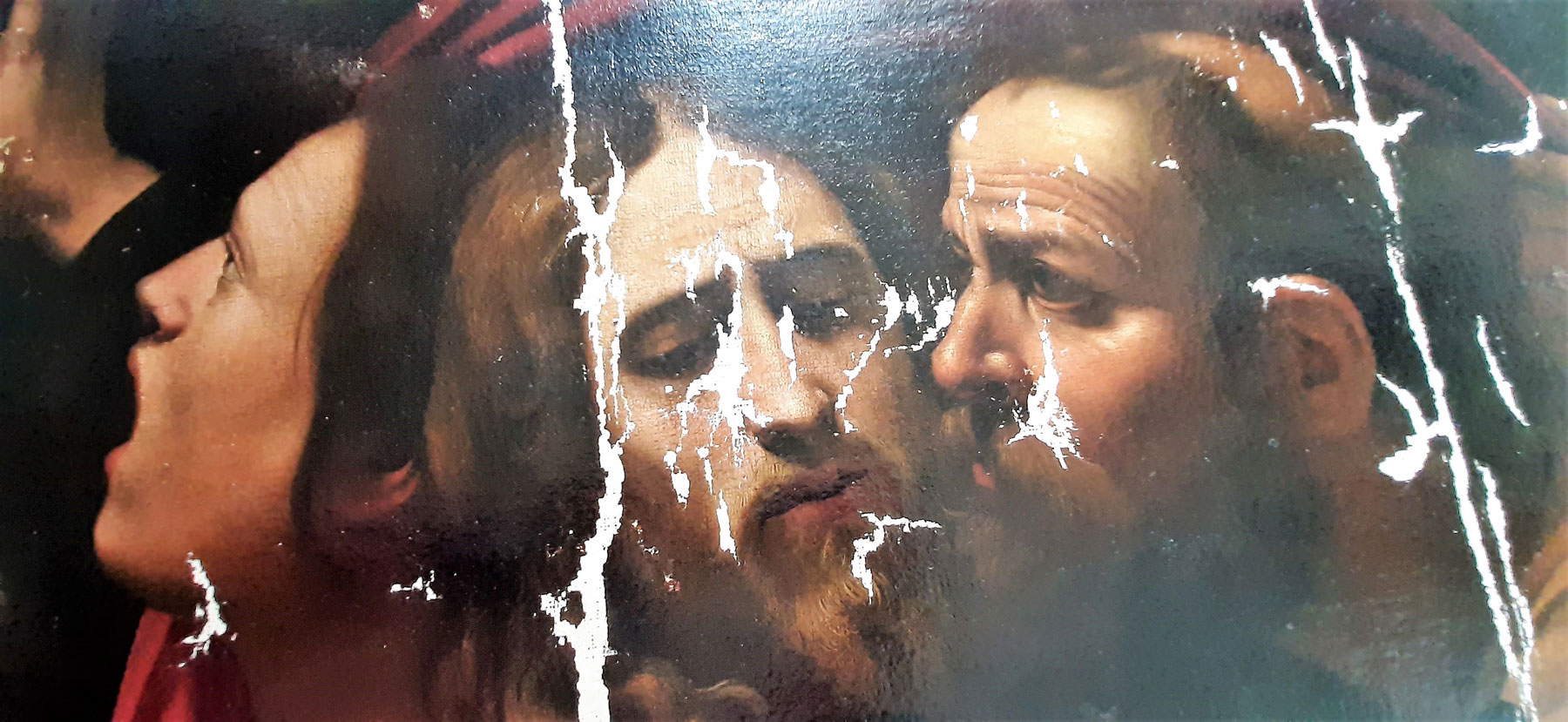

| By Caravaggio, Capture of Christ (early 17th century; oil on canvas, 134 x 172.5 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

But basically this more or less agreeable premise is just to describe how a restoration of a work of art is this. It is suspending that canvas or that fresco from all its functions, and this happens because everything is programmed, made necessary by the passing of the years (it is like doing our car servicing, or as if because of some ailment or because of the ’age that naturally advances inexorably we need a check-up or some treatment), it is not a dramatic thing, it is only “to be done,” at most to be endured. But it is dramatic when we have to do it because something we do not control forces us to do it, and in this case any intervention becomes long, tiring and complicated.

The restoration of this canvas, the Capture of Christ from the Odessa Museum of Oriental and Western Art , is just such a case: difficult, long overdue and also decidedly complex. It is no coincidence that we find ourselves talking about it only nearly eight months later, and even this time I will not be able to give you the news that the work begun in the summer of 2018 is finished.

|

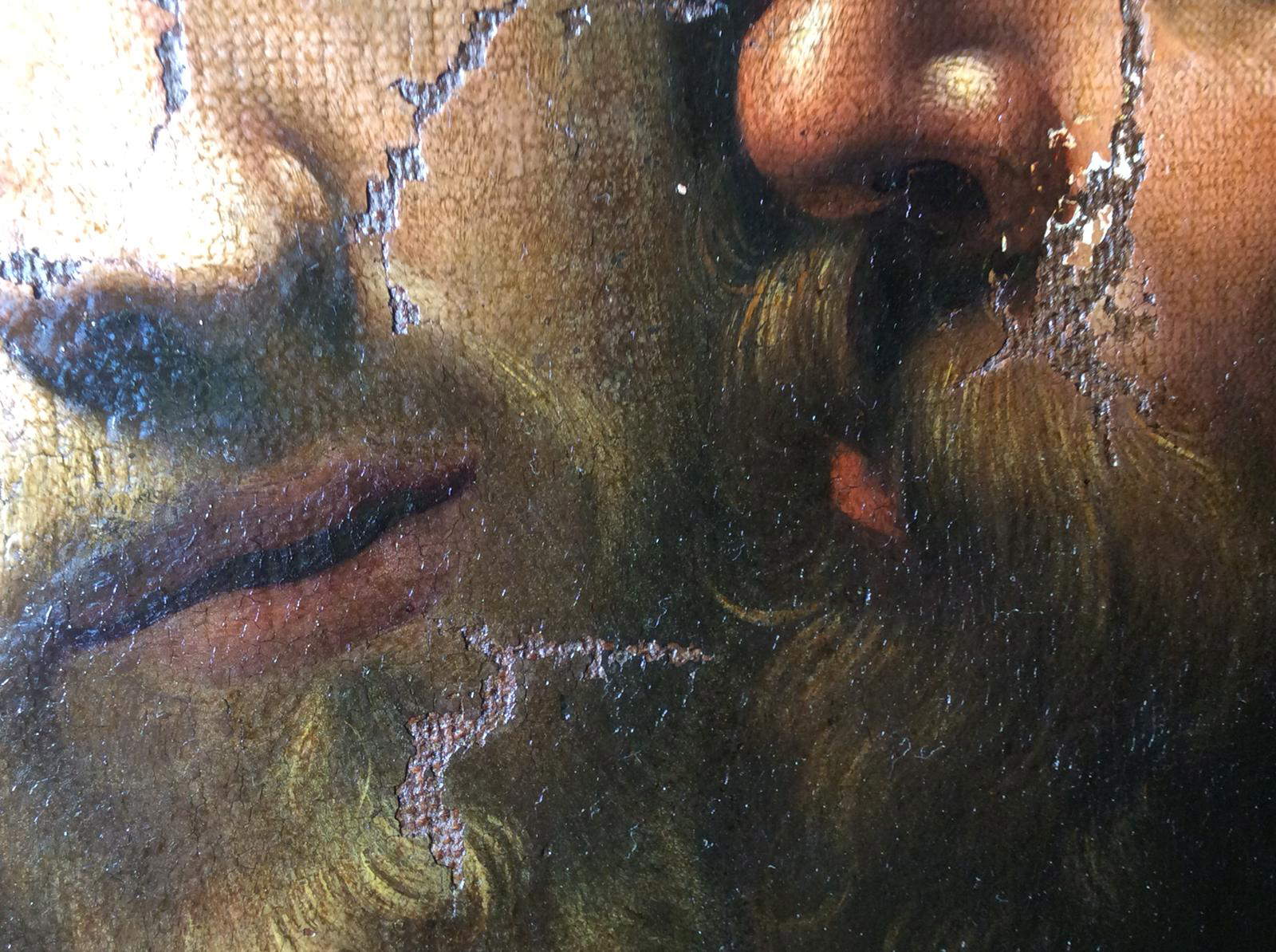

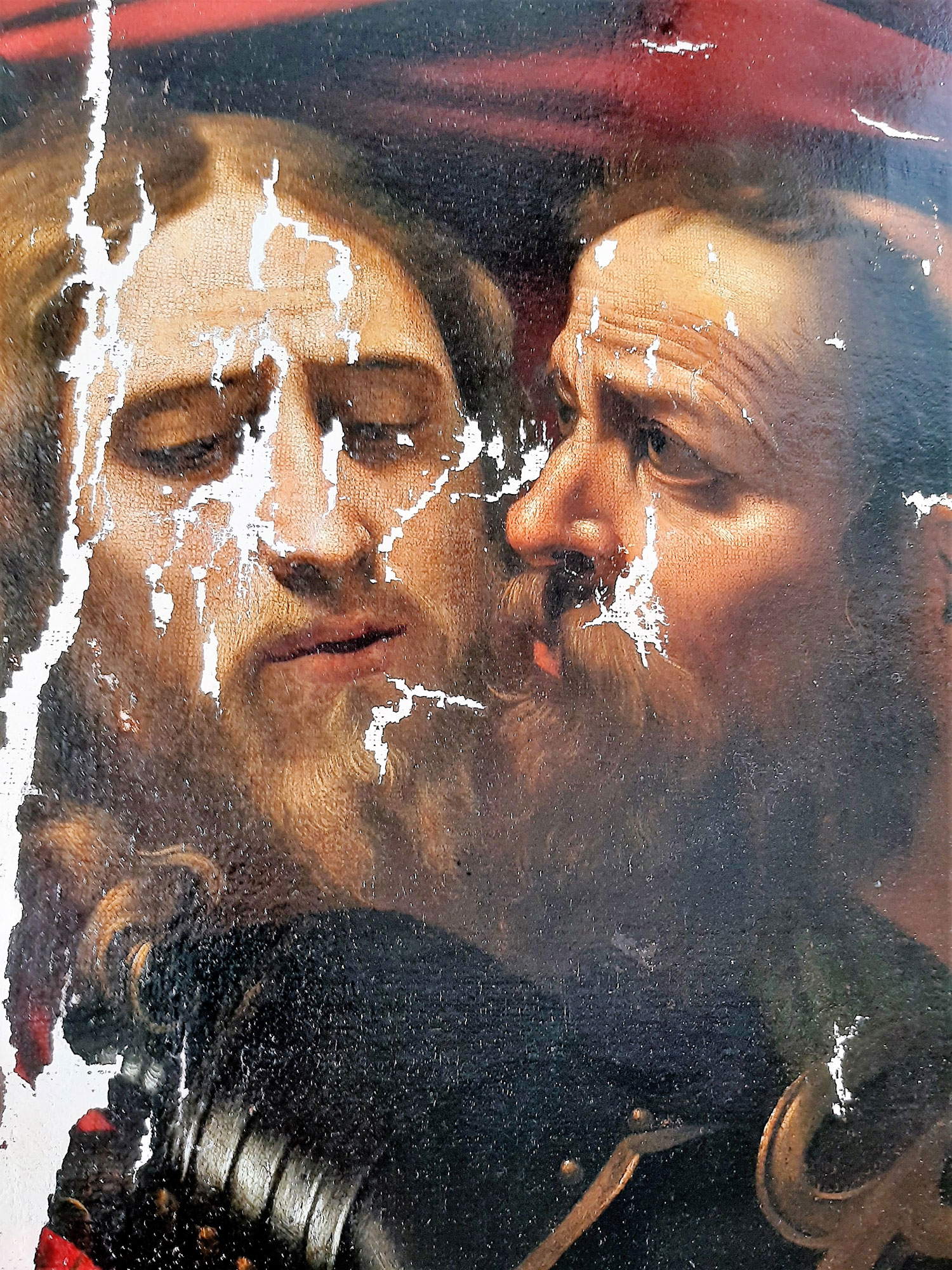

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (July 2019) |

|

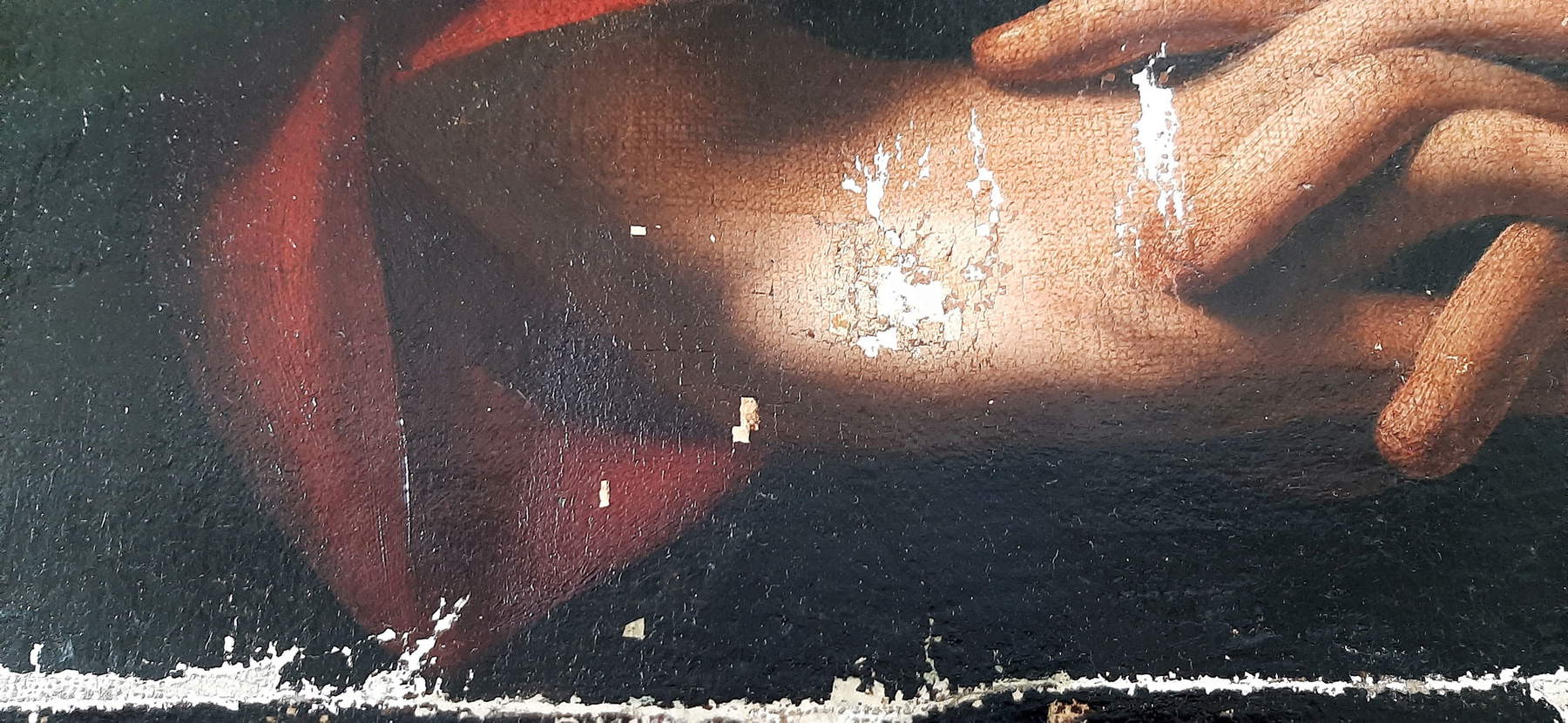

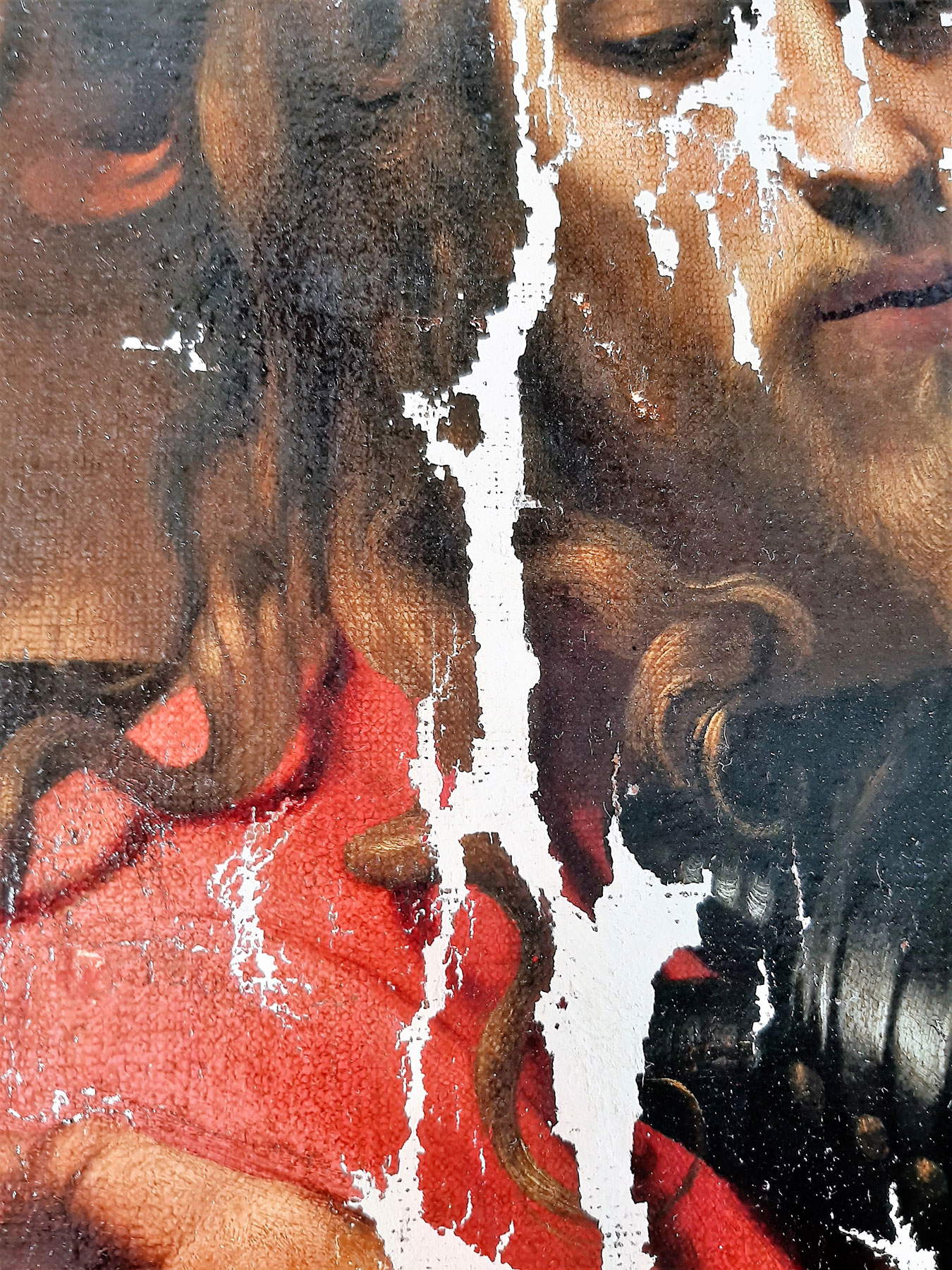

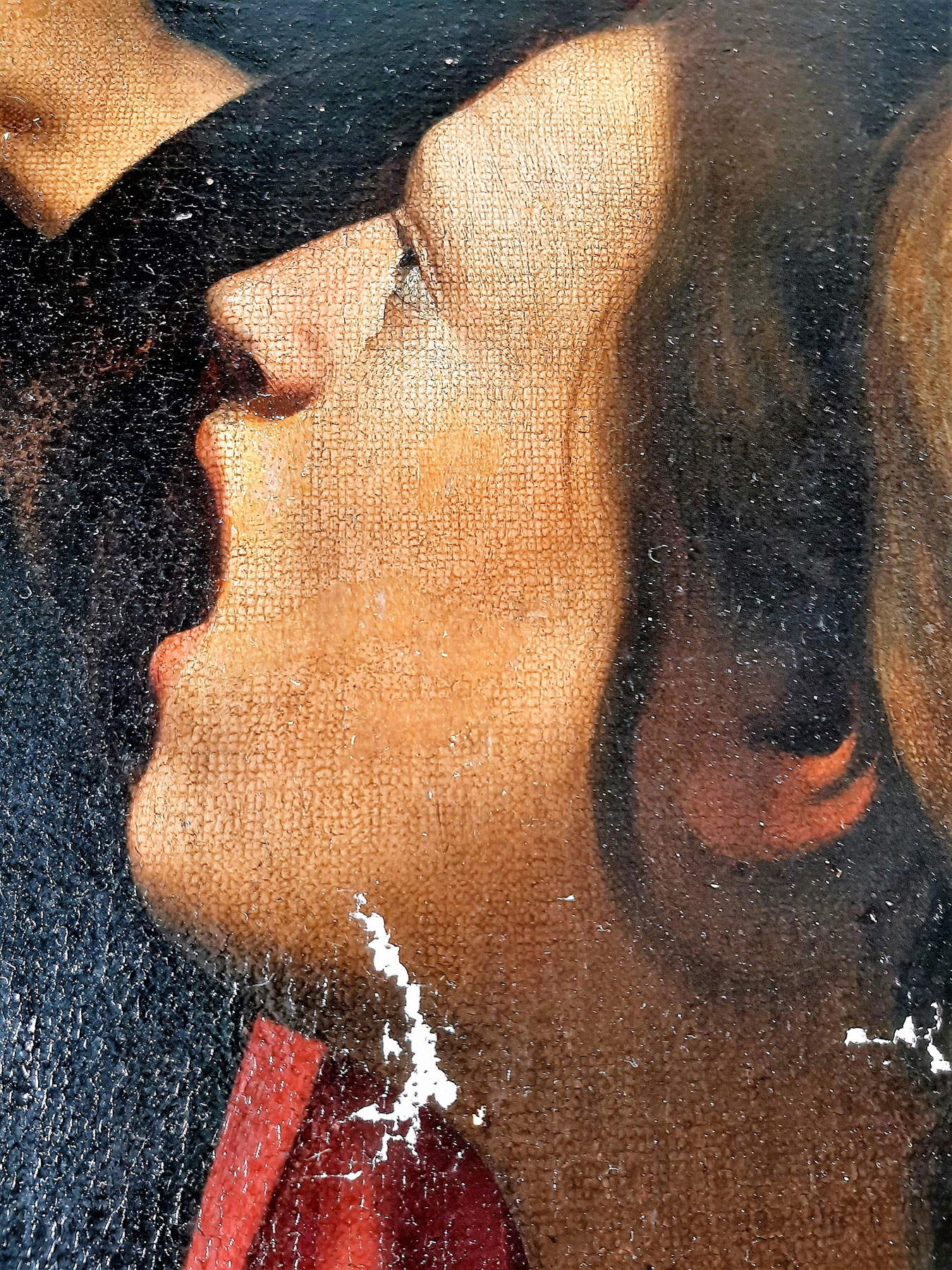

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (July 2019) |

|

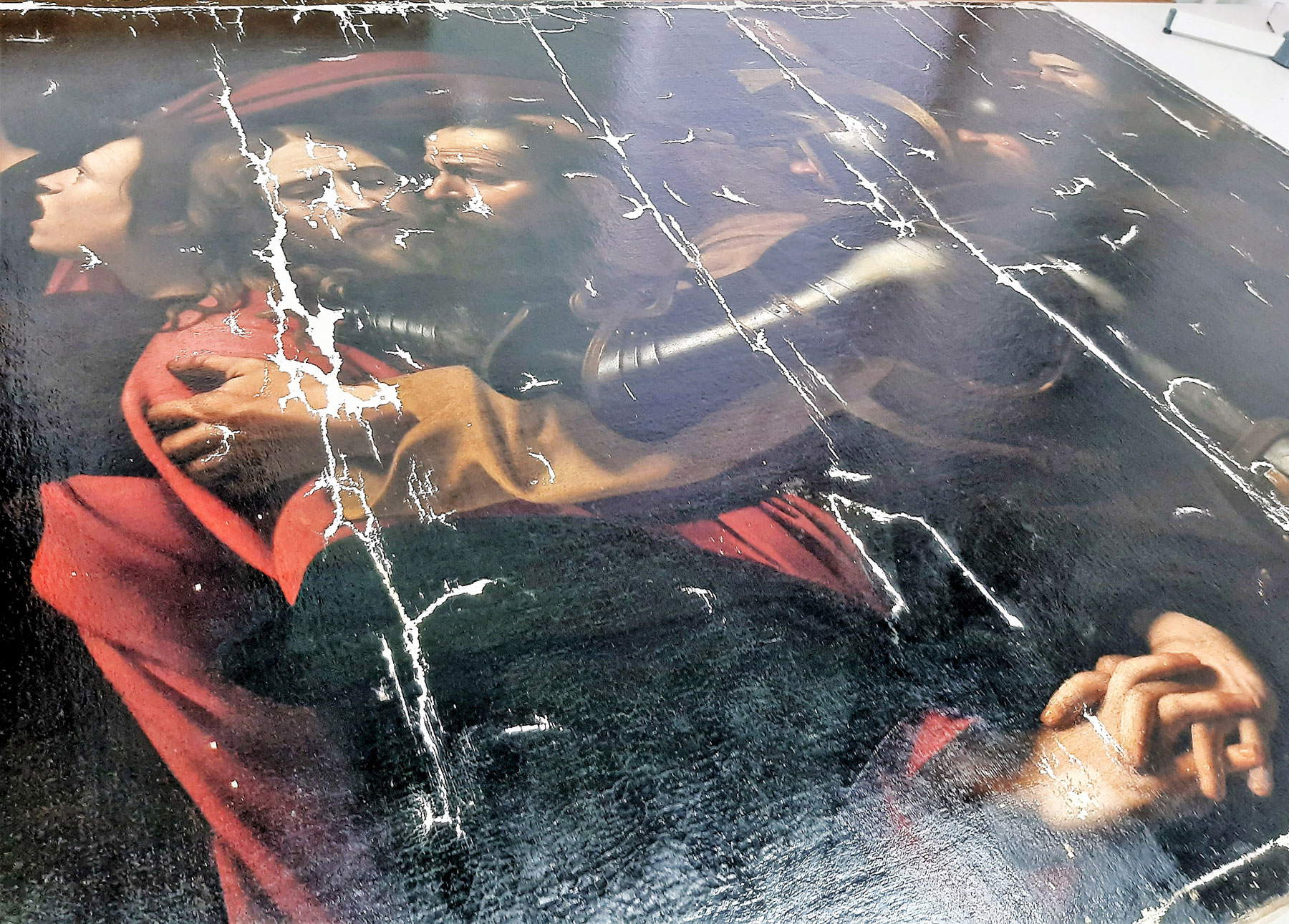

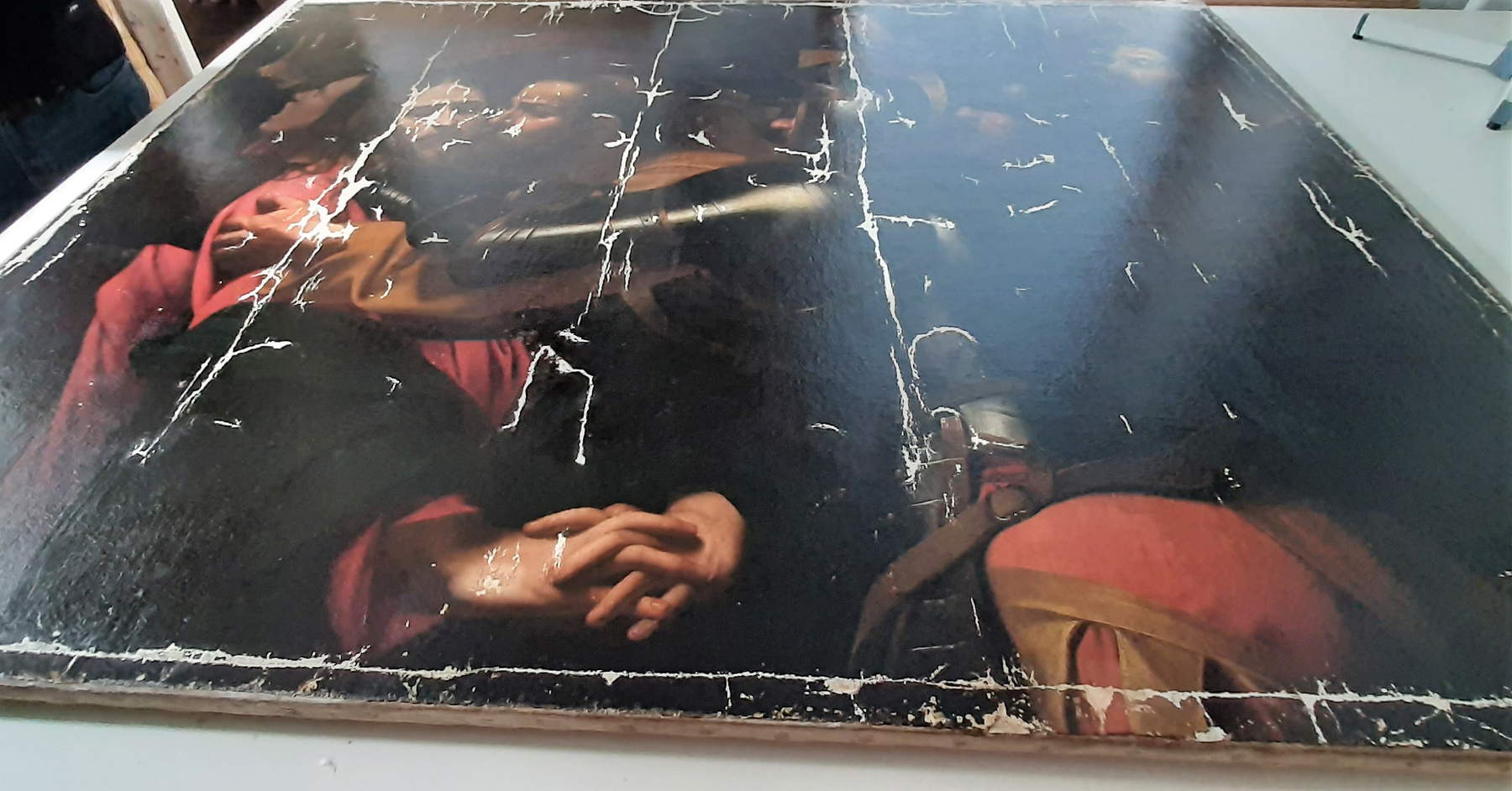

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (July 2019) |

The history of this painting, certainly like so many other works of art over these centuries, has not been simple, and even today not many parts of it are known, certain it is that for the periods that we have been able to document over the years those who lived in this century and last century are decidedly unfortunate.

Painted in Italy in the Baroque period in the early 17th century it was found in Paris in the sumptuous home of one of the most interesting collectors of all time, Alexander Petrovich Basilewsky, from one of the many magnificent Roman aristocratic collections: the Mattei perhaps, or the Colonna-Barberini. Catapulted, presumably in the middle of the nineteenth century, like so many Italian works of art, to Paris, which increasingly in those years had become the crossroads of the great auction houses where masterpieces from all over Europe were battled for sale every day. Presumably those twenty or so years in the multicolored city on the Seine were the best years of this splendid work, displayed in the grand palace known as the Hotel Basilewsky on Avenue de Trocadero. But already in 1868 the great collector tired of paintings, and in need of money to spend, so much so then that he was drawn in an almost mystical way to medieval Christian art, attempted to get rid of his entire picture gallery. The Capture of Christ, or rather Le Baiser de Judas (this is its French title), was not sold or perhaps did not want to be sold: in fact, only two years later, in 1870, it was one of the five paintings that were donated to theSt. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts by the brother of the future Tsar Alexander III, recorded as a gift to Grand Prince Vladimir Alexandrovich by our own Alexander Basilewsky. Important gift, of great value, which, however, within a few years returned with great interest to the donor, as his impressive collection of medieval-Christian art was purchased by the Romanov royal family itself for the astronomical sum of 5 million 448 thousand francs.

The painting seemed to have found its ideal location: the Academy of Fine Arts was a prestigious place, the tsar’s brother Prince Vladimir was its president, of the collection we know the 1874 catalog (the first one that mentions Le Baiser de Judas) that counted as many as 450 works by foreign artists; the Academy was the place where young Russian artists were trained in the knowledge of Western art before the best of them were sent on the Grand Tour.

|

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (February 2020) |

|

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (February 2020) |

|

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (February 2020) |

But evidently Le Baiser de Judas was not to remain in St. Petersburg for long, already in the early twentieth century the work is moved to another city, Odessa. The other new city created by the Romanovs, by Tsarina Catherine II, but with quite different vocations than the imperial St. Petersburg. Odessa was the empire’s great outlet to the sea: the Black Sea. A commercial city, a prestigious gateway to the West, built mostly by Italian architects like the capital, but with a different spirit, more multiethnic and open. The city was for the many who docked at its wharves the calling card for a Russia that continued to be a backward country, but with a great desire to “appear”: and what better could there be than a great museum in which great works from all over the world were displayed, and therefore that painting then attributed to Caravaggio, along with many other valuable works of art on Russian soil, is destined there.

The story is well known: only a few years later, one of the first outbreaks of revolution developed in Odessa itself, then World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, and then again World War II and the Romanian-Nazi invasion of the city, and the canvas disappeared. It was not until 1945, fourteen months after the liberation of the city, that the canvas, along with fourteen other works, was returned by the Catholic Church to the Soviet of the Region. Its first restoration in Moscow lasted a full four years (1951-1955), then another in 1974 to correct some problems not solved in the first intervention, and then in 2006 a very brief conservation intervention at the Museum, and then in July 2008 the theft.

Restoration of the painting began only in the summer of 2018 when the court, which considered it evidence of the crime, after ten years allowed the restoration work to get underway, and as previously documented in the August 2019 article, the painting’s condition was decidedly poor. Until June 2019, work was done to join and suture the parts of the painted canvas that remained attached to the frame with those of the canvas taken away. A complex and delicate operation, which the Ukrainian specialists decided to perform by placing the parts on an even surface of Kraft paper using natural sturgeon glue. The four sides were reinforced with strips of synthetic material (polyamide copolymer), a successful operation that ruled out the need to re-tintel the entire work, and most importantly, safety in the operation of placing the canvas on the frame. At the time of my first visit to the Kiev Institute of Restoration together with Giulia Silvia Ghia (a visit facilitated by the authoritative intervention of Professor Francesca Cappelletti and the director of the Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione e il Restauro Luigi Ficacci), the Italian ambassador was also present, we were able to see the state of the work carried out, which at the moment did not seem to find particular difficulties.

In February this year I was allowed by the director of the Kiev Restoration Institute, Svitlana Stryelnikova, to re-examine the work almost eight months later. I found it stabilized: the Ukrainian restorers made the choice to apply “white-colored putty” to the abraded areas, which reassembled the parts where the pictorial surface had been completely lost. A series of cleaning tests were carried out to verify the safe removal (by testing different solvents) of the high amount of previous restoration work that in some cases did not respect the painting’s original colors. Obviously all this will have to be preceded by the removal of the surface varnishes applied over time, which according to the laboratory experts in some parts are decidedly abundant and oxidized: this operation is essential to make visible the true color of the work.

|

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (February 2020) |

|

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (February 2020) |

|

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (February 2020) |

|

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (February 2020) |

|

| Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ, detail of the painting during restoration (February 2020) |

An overall satisfactory visit, which can record some, albeit still limited, steps forward, especially for those like me and like many, first and foremost my colleagues at the Odessa Museum, who are trembling to see the painting again in its splendor. Of course, the work to be done is still long and, above all, very delicate, because soon the time will come for the pictorial reconstruction of the missing parts, not forgetting that this canvas could be attributed to Caravaggio. For the experts of the Kiev Institute for Restoration it would be a first ever on a canvas of such magnitude, since all the restoration work carried out in recent years on the Capture of Christ, that of 1974 and that of 1951-55 was done at the Grabar Restoration Center in Moscow.

I hope and, indeed, I am sure that this operation will reach its completion, perhaps with a longer time expectation than might have been expected, but the passion and tenacity of the Ukrainian specialists will be rewarded. Not least because the completion of the restoration is only the beginning of a path where there is still a major knot to be untied, that of the Kiev Tribunal’s determination of the status of this work. As already mentioned the work is under the jurisdiction of the trial court, the restoration has been carried out only with a temporary exception to that legal status.

If all these efforts of research, international awareness at the end of the restoration do not lead to the “release from judicial restraint,” this beautiful work after one theft, ten years without intervention, months and months of restoration work and years of doubts about its true attribution will be once again and who knows for how long again “suspended.”

Therefore, I hope that the international scientific community will raise more and more awareness through ad hoc scientific and technical support at this delicate time of restoration and then again to allow the Capture of Christ to live again, and to live a work has only one way: to be exhibited to its public.

The author of this article: Nataliia Chechykova

Storica dell'arte, Consulente per l’Arte Italiana del Museo di Odessa.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.