In the middle of the night, on an ink-black canvas, emerges a phallic figure standing alone on a calm sea, illuminated by a blazing sunset. It is Sea Dick (2022), one of the most recent works by Tala Madani, an Iranian-American artist who for years has been turning painting into a battleground between irony, desire and social critique. In this painting, as in many others, Madani plays with theabsurd to expose the frailties of male power and the contradictions of patriarchal culture. But what happens when the absurd becomes the norm? When the childish element invades the visual narrative to the point that we are unsure whether we are laughing or shaking?

Born in Tehran in 1981, Madani moved to the United States in the 1990s, where she studied political science and visual arts at Oregon State University, then completed an MFA in painting at Yale University in 2006. From the beginning, his art has been distinguished by a visual language that mixes expressionist painting with comic book graphics, creating scenes that oscillate between the grotesque and the comic. In Braided Beard (2007), a man has his beard braided by invisible hands. The gesture, which at first glance appears funny, tender even, on second glance disquiets: why does the man not resist? Why does he look lost, almost catatonic? Where are we? In a childish dream, in a punishment, in a ritual? Perhaps all at once.

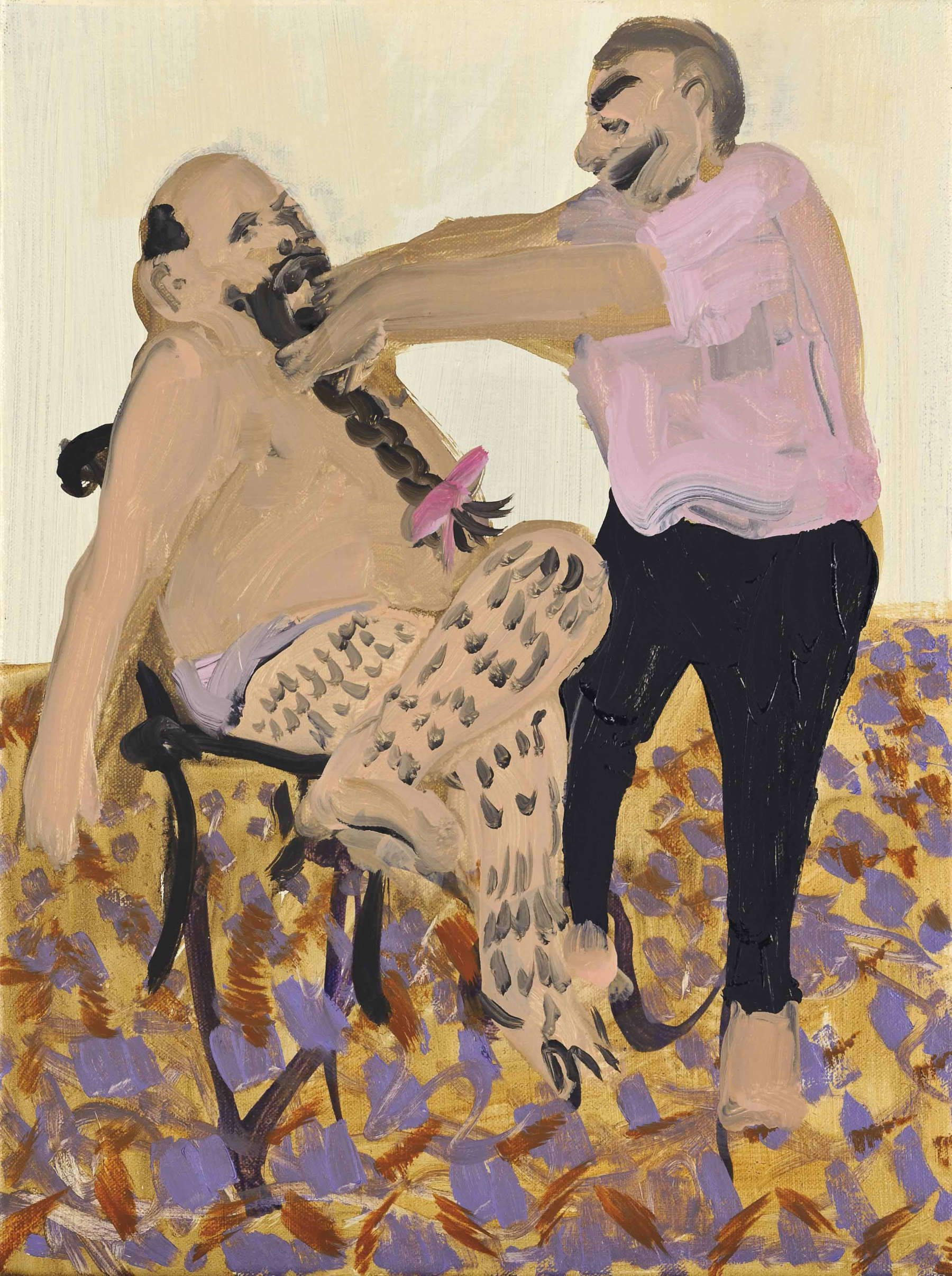

Madani does not build worlds: she disintegrates them. Her backgrounds are bare, flat walls or undefined environments where action, often reduced to a few repeated gestures, takes over logic. In Nosefall (2007), a man literally loses his nose, which slides down his face like butter on a hot frying pan. And you ask yourself, what do we lose when we lose our features? The identity? The role? The chance to be seen? And again: why are these men always alone or in groups that look like gangs of badly raised children, sculpted into a fake masculinity, unable to articulate complex desires or thoughts? Is this perhaps a portrait of the generation that has failed to become adults? A humanity that, after centuries of domination, no longer knows what to do with its own body?

Madani gives us no answers. Nor does she claim to have them. He does something more risky: he puts us in front of images that function as distorting mirrors. And the beholder is forced to stand there, staring at himself. How much of us is there in these humiliated men? Why do they remind us of our father, our brother, a colleague, ourselves? Madani does not paint “against” anything, it is not a pamphlet against patriarchy, nor a simplistic allegory of power. It is a more subtle, more visceral narrative. It is an opening on the exact moment when certainties fall apart. Where violence, eros, tenderness and shame also mix into one thick, carnal, sticky fluid.

Her colors? Pasty, often violent. The outlines are imperfect, smudged. As if the image is about to run away. Perhaps because nothing is stable, not even identity. Not even the body. Not even the very idea of “man” or “woman.” Tala Madani forces us to look closely at that intimate, ridiculous, tragic and irredeemable moment when the mask falls. But what happens when there is no longer a face underneath? And do we, who are there to watch, manage to remain impassive? Or do we feel exposed, seen, even mocked? Because perhaps, in the end, what really scares us is not the awkwardness of his characters, but recognizing ourselves in them.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.