Brassaï, pseudonym of Gyula Halász (Brașov, 1899 - Nice, 1984), stands as a central figure in 20th-century photography, whose work is inextricably linked to his ability to capture the innermost and most mysterious soul of Paris. Of Hungarian descent, born in Romania but deeply rooted in the French capital, his adopted city, he was affectionately referred to by his writer friend Henry Miller as the “living eye,” a nickname that well expresses his extraordinary vision and penetrating ability to capture the essence of the world. His vast and multifaceted artistic output (the focus of a significant retrospective at the Saint-Bénin Center in Aosta, scheduled from July 19 to Nov. 9, 2025, curated by Philippe Ribeyrolles, a scholar and grandson of the artist: more than 150 vintage prints are presented alongside the photographer’s sculptures, documents and personal objects, offering an in-depth and previously unseen look at his work) shows that Brassaï was not just a photographer: his figure extends to that of a painter, sculptor and intellectual, a multifaceted artist whose sharp and poetic gaze continues to inspire new generations.

Beginning in 1924, just 25 years old, Brassaï immersed himself in Parisian cultural fervor, establishing deep ties with the likes of Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí and Henri Matisse, and exploring areas ranging from the Surrealist movement to the world of fashion. His photographs have become celebrated images: from enigmatic night views of the French capital, often shrouded in fog or drenched in rain, to portraits of celebrities and ordinary people, from bustling suburban clubs to graffiti on Parisian walls, Brassaï has been able to chronicle the myriad faces of Paris.

Although his work is often traced to the French “humanist school,” such a definition would be reductive, not fully capturing the complexity of his approach, which combined instinct, technique and a deep curiosity for the unexpected. Brassaï, as a “creator of images,” as he considered himself, aspired to catch a flash of light in the darkness, finding poetry in the humblest of everyday life and conferring dignity and uniqueness on every human being and object captured by his lens. His explorations led him to document a “secret,” underground Paris of bars, folk dances, cabarets and brothels, showing marginal humanity as naturally as he frequented the elites. Let’s look at ten things you need to know to start learning about this important photographer.

Gyula Halász adopted the nickname “Brassaï” in 1932 as a tribute to his hometown, Brașov (“Brassó” in the Hungarian language), once part of Hungary’s Transylvania (in the early twentieth century, the city was in fact majority Hungarian). Despite his Magyar roots, Brassaï chose Paris as his permanent home in January 1924, settling on the Left Bank and remaining there for the rest of his life, so much so that he naturalized as a Frenchman in 1949 and felt fully part of transalpine culture.

This deep and enduring connection with the French capital was such that his writer friend Henry Miller affectionately nicknamed him “the eye of Paris.” However, Brassaï himself preferred a more nuanced and personal description of his artistic identity, describing himself as “a foreigner from the frontier between East and West looking at Paris with his Transylvanian eye.” This outsider’s perspective, combined with an intimate familiarity with the city, allowed him to capture and narrate the nocturnal, mysterious and life-soaked atmospheres that characterized the metropolis of the time, making it an inexhaustible subject of his photographic production. His name, therefore, has become synonymous with his unique and profound vision of the Ville Lumière.

Brassaï distinguished himself as an artist of remarkable versatility, enriched by a cosmopolitan education and a range of interests that went far beyond photography alone. His studies took him first to the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest and later to Berlin, where he had the opportunity to meet and associate with such leading figures of the European avant-garde as Vasily Kandinsky, László Moholy-Nagy, and Oskar Kokoschka.

His insatiable curiosity was not limited to the visual field: Brassaï was also a draughtsman, painter and sculptor, and his choice not to specialize in any one discipline was a hallmark of his artistic personality. As he himself admitted, “There are too many things that interest me, it’s a tragedy.” This sort of artistic inconsistency was actually his consistency: he “would always refuse to specialize, wanting to preserve the freshness of the amateur’s vision and the expertise of the professional,” as Philippe Ribeyrolles recalls. He assiduously read works by masters such as Goethe, Proust, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, a cultural background that sharpened his spirit of observation and guided him in his search for the most recondite and misunderstood aspects of reality. This multidisciplinary approach and a multifaceted sensibility soon made him a prominent personality in Parisian intellectual circles, capable of weaving deep relationships with the leading figures in the art and culture of his time.

Brassaï’s approach to photography was almost an inescapable destiny rather than a deliberate choice: it was the medium that imposed itself on him. From his early childhood, during a stay in Paris with his family in 1904, images of the city settled in his memory, evoking sensations and memories comparable to Proust’s famous madeleines. As an adult, a persistent desire drove him to want to rediscover and relive those childhood visions.

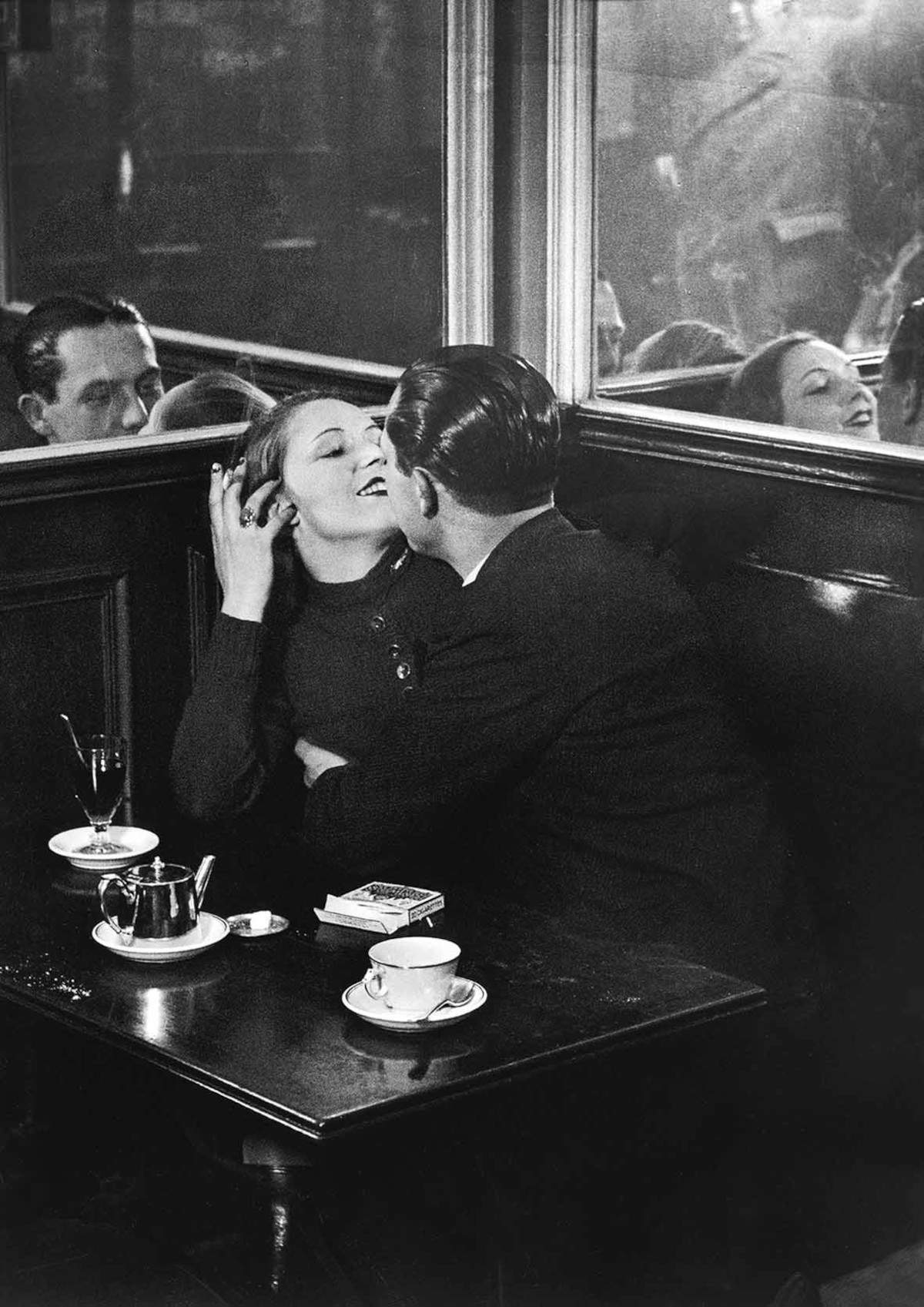

The turning point came in 1929, when he devoted himself definitively to photography. Before then, he had worked with the Rapho agency and felt a growing need to accompany his writings with his own images, thus achieving a fusion of word and vision. His photographs of a nocturnal Paris, shrouded in mystery and illuminated by streetlights, car headlights, fog or rain, became famous, capturing the very essence of the French capital.

The culmination of this exploration was the publication in 1933 of his book Paris de nuit, a work that not only met with extraordinary success but also entered fully into the history of 20th-century photography, establishing him as the undisputed master of night photography. His images not only documented, but revealed an “other” Paris, that of the night owls and rêverie, a genre that was consolidated through his groundbreaking work.

Brassaï was not content to be a mere documentarian of reality; for him, photography was a means of interpreting and sublimating the visible world. He called himself a “creator of images” and considered his work a “mental construction based on reality.” This perspective led him to a deep reflection on composition, which he considered as crucial as the subject of the photograph itself. His philosophy was clear: “One must eliminate everything superfluous, one must guide the eye like a dictator!”

His techniques for capturing the magic of the night were ingenious and personal. To measure shutter speeds, he used a cigarette, calculating exposure based on its consumption. He exploited every available light source-from car headlights to gas lamps, from the moon to snow and even fog-to sculpt volumes and create supernatural atmospheres that transformed the rigor of architecture and outlined faces and figures emerging from shadow.

In his workshop, Brassaï did not limit himself to a simple transcription of the negative. He was actively intervening in the image, cropping, building and modulating the densities of blacks to maximize expressiveness, with the goal of recreating in the viewer the same feelings felt at the time of the shot. Her quest was for a “flicker of light in the darkness,” as Daria Jorioz called it, which managed “to stop a moment of poetry in everyday misery, to consider every human being interesting and unique, to smile at the pettiness of the world, celebrating the sensual beauty of a smile or the ambiguity of a stolen gesture, recounting a deserted street at the end of the night and piercing the darkness with a camera.”

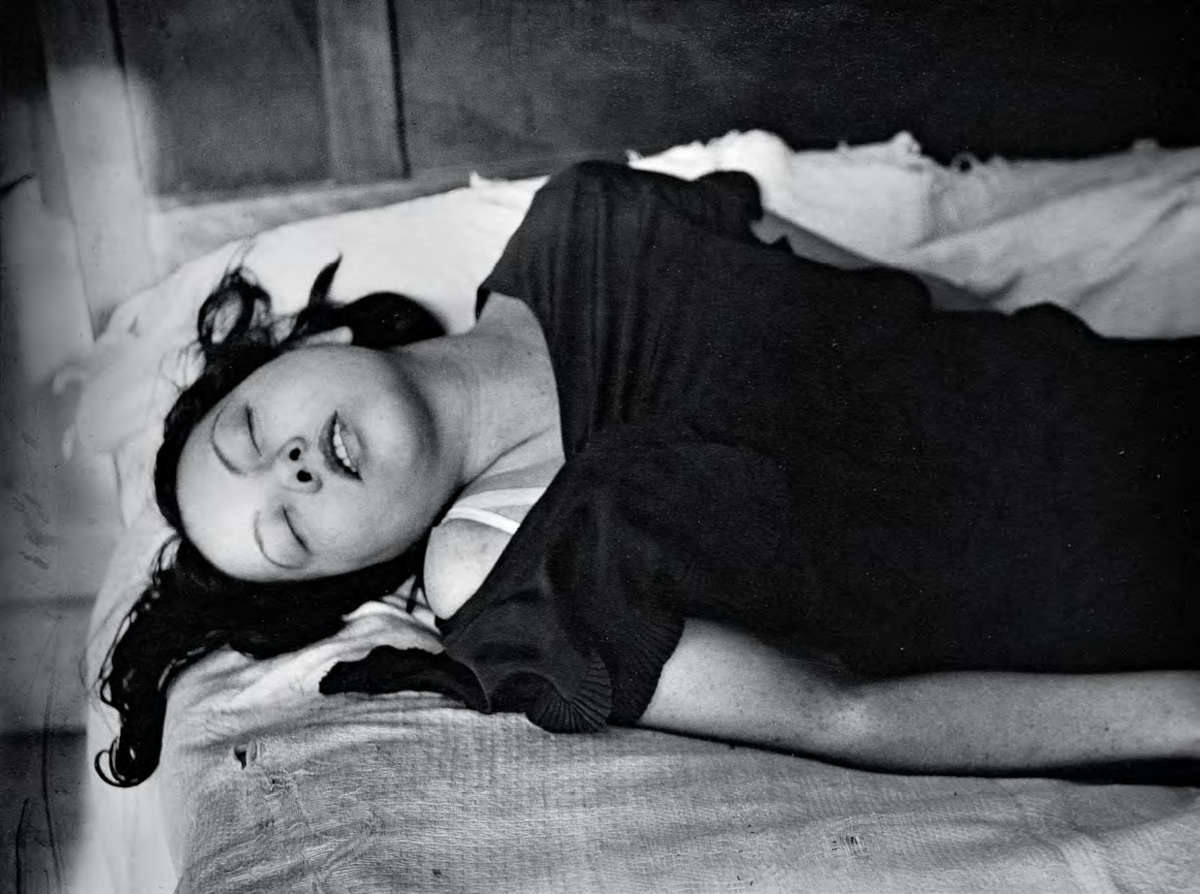

A central and fascinating aspect of Brassaï’s work was his exploration of what he called Paris secret, a marginal and often forgotten world that coexisted with the elegance of the Ville Lumière. The artist had a deep fondness for what he called the humanity of the slums, the last, the poor, the delinquents, the beggars. His readings of authors such as Mac Orlan, Zola, Stendhal, Mérimée, and Nietzsche fueled his desire to penetrate this subterranean universe, leading him to frequent Parisian elites and slums indifferently.

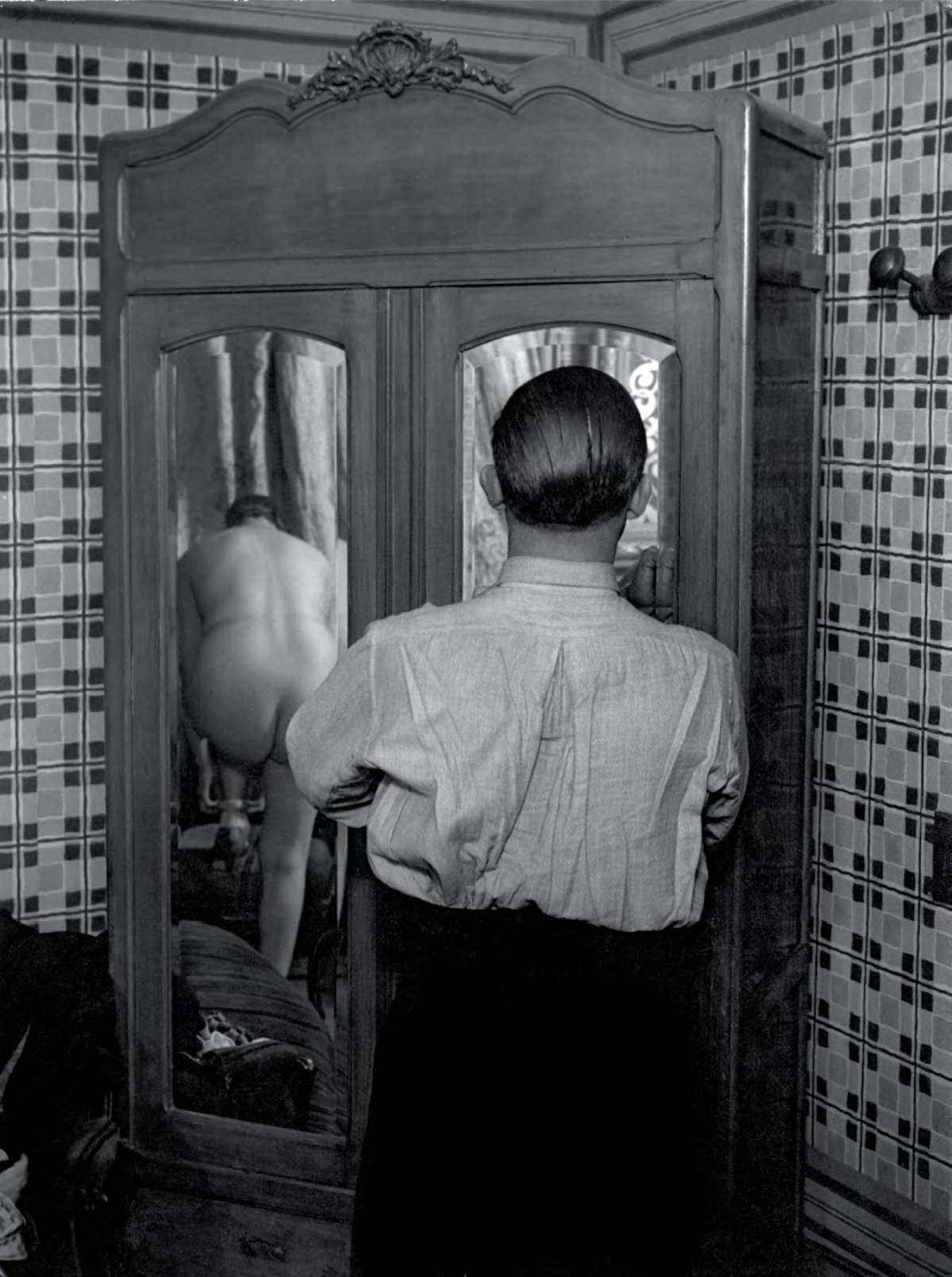

Brassaï moved with ease between dance halls with multicolored lanterns and bars with red moleskin benches, where workers, prostitutes, clochards, artists and lonely wanderers met. He documented the world of cabarets, folk dances, and even brothels, which he poetically called the “houses of illusions,” where prostitutes were “daughters of joy” or “beauties of the night” and crooks became one-night stands. This allowed him to create a constant fresco of the “Paris-Canaille.” His forays into these often dangerous environments led him to risk his life. Often mistaken for a police informant because of his camera, Brassaï had to earn the trust of his subjects, sometimes befriending petty criminals so that he could photograph them and get them to pose. Through these shots, he rescued from oblivion a complex and storied humanity, offering invaluable testimony to a dying popular and marginal France, for which he felt great tenderness.

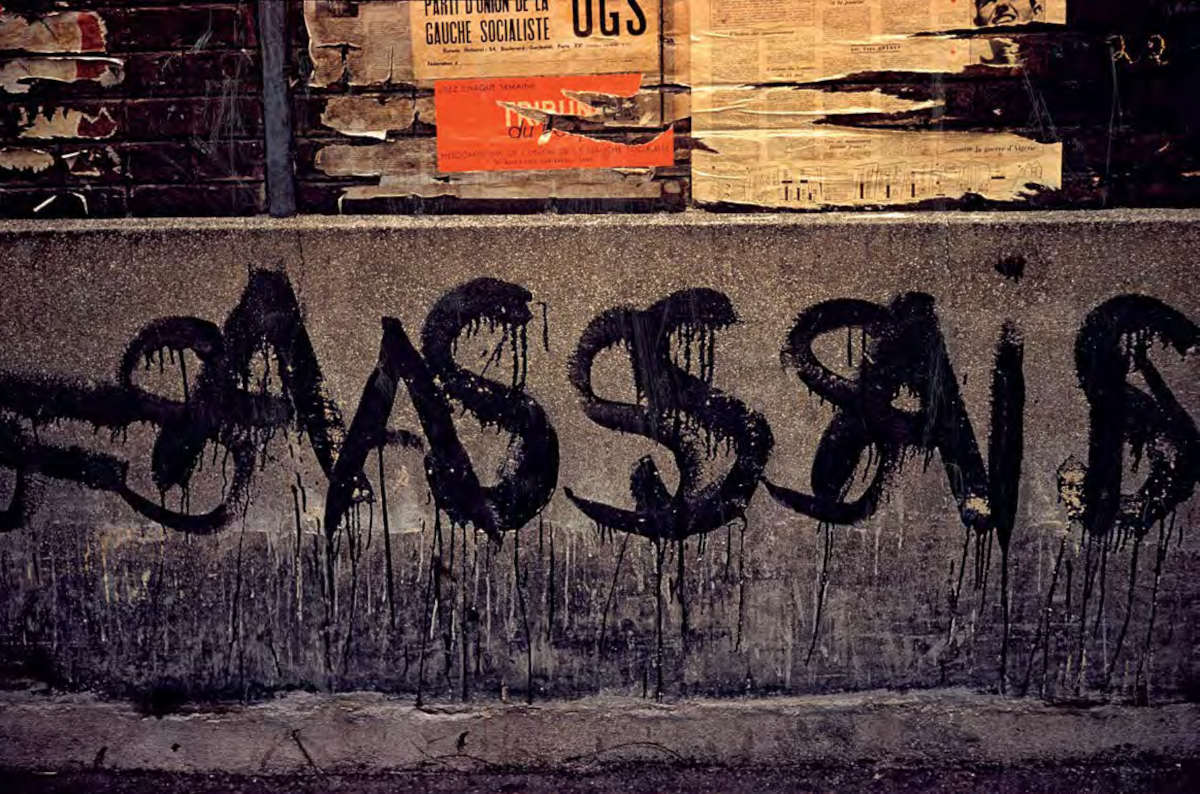

One of the most significant series in Brassaï’s oeuvre is his extensive documentation of graffiti on the walls of Paris. For him, the wall exerted an almost primordial fascination, and graffiti represented a true “language of the wall,” evidence of the most humble and spontaneous expression of humanity. The artist considered them the greatest gallery of primitive art, comparing them to the drawings of prehistoric men in caves and seeing in them the origins of creativity and writing.

His search for these “human scratches” began in the 1930s and continued for more than 30 years, with Brassaï meticulously noting places, dates and transformations in an attempt to save them from the wear and tear of time and oblivion. This fascination with Art Brut and the marginal arts was shared and appreciated by artists such as Georges Braque, Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso, and Jean Dubuffet.

The culmination of this work was the 1960 book Graffiti, where he classified his findings into nine categories. The importance of his graffiti work was recognized internationally with a solo exhibition at MoMA New York in 1956-1957, entitled Language of the Wall. Parisian Graffiti Photographed by Brassaï, which was highly successful.

Brassaï, with his keen sensibility and innate curiosity, fit naturally into the vibrant intellectual and artistic circles of Paris, forging friendships and collaborations with many of the most influential figures of the 20th century. His circle included such giants as Fernand Léger, Georges Braque, Joan Miró, Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti and, most notably, Pablo Picasso. With the latter, he developed a deep friendship and an “aesthetic complicity” based on elective affinities, sharing a fascination with the nonconformist circles of the Folies Bergère and the mysterious world of the Circus Medrano.

His closeness to the Surrealist movement was clearly manifested through his collaboration with the avant-garde magazine Minotaure, where his photographs were published alongside those of Man Ray, cementing his reputation. Through “Minotaure,” he met and collaborated with Surrealist writers and poets such as André Breton, Paul Éluard and Salvador Dalí. With Dalí, he made the “Sculptures involontaires” series, transforming everyday objects into expressions of Surrealist abstraction. Brassaï also frequented Jean Cocteau, Jacques Prévert and Samuel Beckett, contributing to an intense Parisian cultural season.

Brassaï’s fame quickly transcended French borders, consolidating through prestigious collaborations and numerous international trips. One of the most significant partnerships was with the renowned American magazine Harper’s Bazaar, for which he worked assiduously from 1937 until the 1960s. For the magazine, Brassaï produced portraits of numerous leading figures in French artistic and literary life, many of them his friends. These portraits would later flow into the volume Les artistes de ma vie, published in 1982.

His travels were not limited to Europe; Brassaï explored the world, producing reportages, including in color, in places unfamiliar at the time such as Greece, Turkey, Morocco, and Brazil, as well as in the United States, England, and Ireland. His first trip to the United States, in 1957, was an enlightening experience: there he met photographers such as Walker Evans and Ansel Adams, the latter being particularly appreciated for his vision of nature and the quality of his prints. This extensive international activity testifies to his tireless curiosity and his ability to capture the essence of different cultures and landscapes.

For Brassaï, the photographic act did not end with the shot; the final print was the true culmination of the work, giving it full artistic dignity. He firmly supported the complete authorship of the process, stating with conviction, “A negative means nothing to a photographer like me, it is only the author’s print that counts. That is why I always wanted to make my prints myself.” This dedication led him to personally develop the negatives and make all the prints in his workshop, maintaining total control from the beginning to the end of the creative process. Brassaï, recounts his wife Gilberte in an interview with Annick Lionel-Marie published in the Aosta exhibition catalog, “developed the negatives, prepared the fixing baths, and made the prints and enlargements himself in his workshop. He had dozens of bottles containing different preparations, and many chemical formulas hung on the wall. He would stay awake and work long hours, especially at night; I could hear the ticking of the metronome he never wanted to part with. He liked to control the process from start to finish; you never allowed anyone to make prints (except for sizes larger than 40 × 50 cm, which his enlarger could not do).” This meticulousness allowed him to bring out, through the quality of the print, the same intense feelings he felt at the time of the shoot.

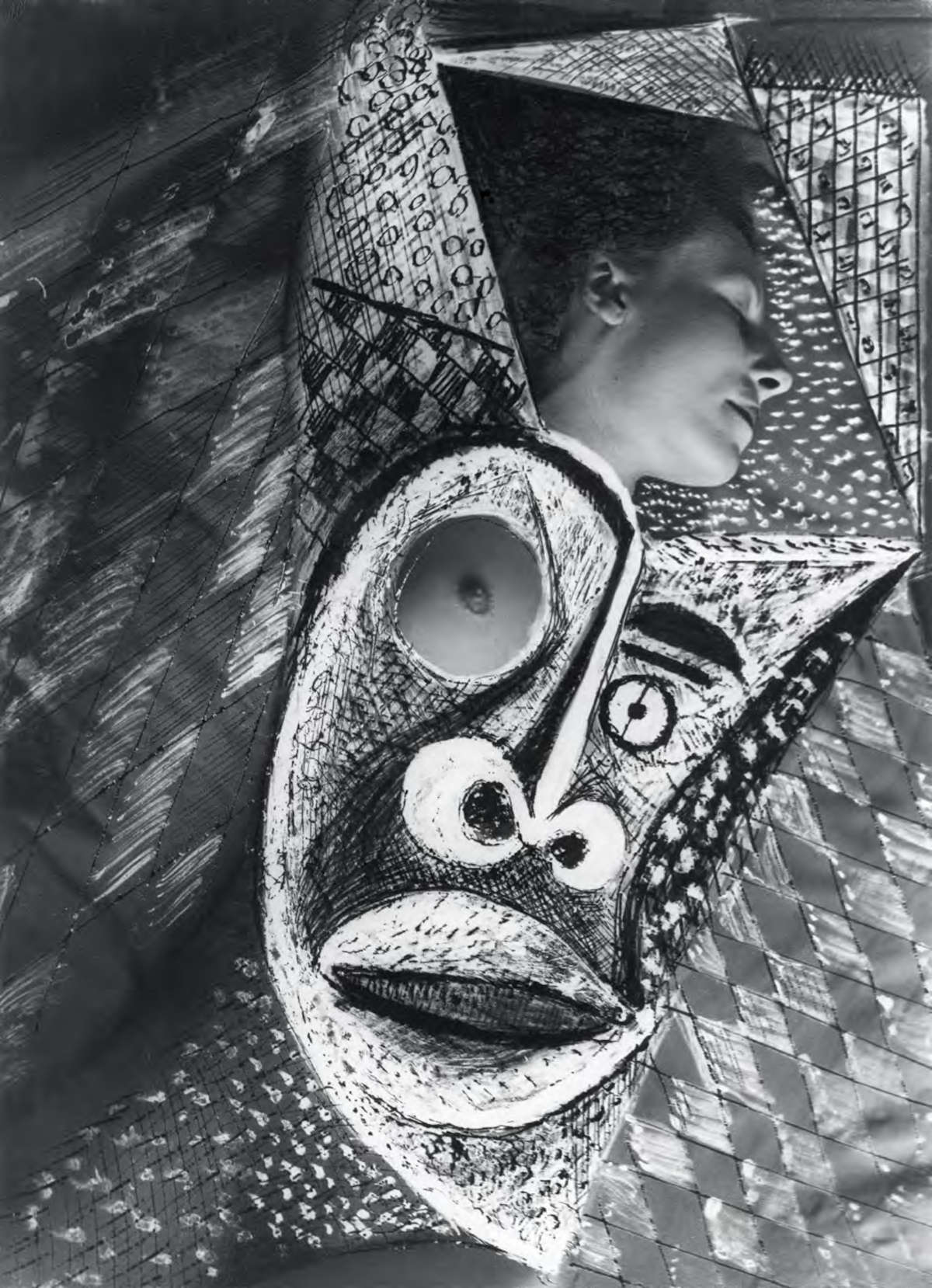

Throughout his career, Brassaï also developed an innovative series he called Transmutations. In these works, he would intervene directly on the original negative (often glass plates) with a nib, scraping and elevating with Indian ink. This process of “voluntary mutations” transformed the initial image: the original photograph vanished, giving way to new forms that combined realism and dream, acquiring a new visual existence. This technique testifies to his continuous expressive research.

In addition to his photographic mastery, Brassaï distinguished himself as a multifaceted intellectual, a prolific writer, and even a filmmaker. His passion for writing manifested itself in a vast textual output, which included lengthy prefaces and significant essays. Among his most notable literary works are the novel Histoire de Marie (1949), the illuminating Conversations avec Picasso (1964), a seminal work collecting 30 years of exchanges and descriptions of the artist’s ateliers, and Le Paris secret des années 30 (1976), a fresco of a popular and marginal France. His last book, Les Artistes de ma vie (1982), collects testimonies and recollections of all the artists he frequented.

Brassaï was not indifferent to the power of words, as evidenced by his commentaries and his reflection on the transposition of spoken language into writing. His indefatigable mind also extended to film: in 1956, his short film Tant qu’il y aura des bêtes, shot at the Vincennes Zoo, was awarded for originality at the Cannes Film Festival.

He died on July 7, 1984, just as he was completing a book on his beloved Marcel Proust, to whom he had devoted several years of his life, trying to identify links between his literary work and photography. He was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery, the heart of the Paris he had so celebrated and documented for half a century. He was, Ribeyrolles points out, “above all a walker who fixed his gaze on his era, within a simple everyday life that he wanted to sublimate as a plunderer of beauty of all kinds and that he managed, in this way, to save from time and oblivion.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.