Among scholars of art history, the name of the town of Atri, located on one of the first hills rising from the coast of the province of Teramo, is quite recurrent by virtue of the thirteenth-century cathedral and the medieval and Renaissance frescoes inside it. The centrality of the building in the local identity is also reflected in tourism promotion; in fact, the well-preserved historic center has numerous museums and monuments, including eleven churches: among them is San Francesco, occupied until half a century ago by the Friars Minor, considered one of the most interesting examples of Baroque art in Abruzzo.

|

| The church of San Francesco in Atri. Photo credit. |

The church is located almost halfway down the Corso and is the largest after the Cathedral, so much so that it accommodates services when the latter is closed. Ledificio had always suffered from structural problems, complicit with dampness, which led to its closure due to unfit for use following the April 6, 2009 earthquake; a lack of funds at the diocesan Curia prevented restoration work from being started, and now the recent tremors, also well felt in Abruzzo, have aggravated the situation. The artistic history of Abruzzo’s localities is marked by earthquakes: beyond the practical intervention of reconstruction, earthquake events stimulated the arrival of foreign workers and the upgrading of artists from the region. This was the case after the two great earthquakes of 1703 and 1706, which devastated LAquila and Sulmona and were the impetus for the arrival of sculptors, architects and painters from Rome, Naples and Lombardy who broadened the horizons of Abruzzi Baroque art.

The artistic consequences of those two earthquakes can still be seen in the region’s monuments, and not only in the Apennine centers, marked by collapse and destruction: even the localities located toward the Adriatic coast (gravitating on Chieti and Teramo), at low seismic risk, where the damage was certainly minor or nil, took advantage of the artistic liveliness and undertook renovations, especially of churches. These were interventions aimed at modernizing such buildings and trying as much as possible to adapt them to the norms of post-Tridentine ecclesiastical architecture set by St. Charles Borromeo in the Instructiones (1577), where the 600 had acted only superficially on the structure of the building because of the crisis that invested the Kingdom of Naples at that time and that, although it had not halted artistic production, certainly curtailed major architectural endeavors in peripheral regions (but the loss of seventeenth-century evidence due to the aforementioned earthquakes must be taken into account). Spy of how the great eighteenth-century building campaign was, for these hilly or coastal areas, a need for renewal and adaptation to the canons of the Counter-Reformation (which in small towns focused on the interior), is in several cases the fact that the exterior was not affected by works.

In Atri as many as six churches were renovated in the early eighteenth century, but only two of them underwent an integral project that included the facade, including St. Francis. The origin of this complex of Franciscans is thirteenth-century, but the precise time is unknown: by mid-century it was existing and flourishing since a friar in the odor of sanctity, Blessed Andrew, died there already (1241), and the chapter of Narbona elevated it to chief town of the Custodia Adriensis (1260), one of the six districts into which the Franciscan province dAbruzzo(Provincia Pinnensis) was divided. Since St. Francis visited nearby Penne in 1215, local tradition has attributed the birth of the Atrian convent to this event. As is typical of Franciscan convents, it was located in a busy area, almost opposite the square used as a marketplace. From the remaining medieval structures, it is inferred that it was one of the largest Franciscan churches in Abruzzo. The church must have had three naves of equal height, with the central much wider than the side naves, modeled after Santa Croce in Florence; it was elevated, by virtue of the slope of the land, but much less than now. The facade, as today set back from the Corso, opened onto a raised widening reached from the slope on the left of the church (vico San Francesco). Around the high podium of the church several stores opened, almost as an extension of the nearby Market Square.

The right side preserves various vestiges of the ancient building: there are long walled single-lancet windows; a few gargoyles for draining water that still possesses, much faded, the zoomorphic conformation (the famous gargoyles); the ruins of the presbytery, with the walled, pointed arch triumphal arch decorated with crochet capitals; the entrance to one of the podium stores, with a carved image of St. Francis (early 15th century) to indicate a property of the friars. Also two-thirds to fourteenth-century are the bell gable, with a bell from 1265, and the pointed archway on the left side, by southern craftsmen, connecting the church to the convent, beneath which is the tombstone of Giacomo di Lisio, an Atrian physician from the late 1300s, removed from the church during eighteenth-century work and later reassembled here: the loss of physiognomic features gave the deceased evanescent features and brought him into popular imagery as lu mammocce (in dialect: the puppet), a children’s bogeyman.

|

| Lu mammocce (photo by Gino Di Paolo) |

The radical change came in the early eighteenth century. Not only was the interior baroqued, not only was the facade redone: the very plan of the building changed. The Latin inscription in couplets contained in the stucco cartouche on the counterfacade indicates that in 1715 the church was re-consecrated and reopened after quinque retro lustris [...] ruit (five lustri addiri [ ] ruined). The church in fact collapsed as a result of an earthquake that did not, however, occur in Abruzzi territory: on December 23, 1690, a strong earthquake had shaken the Ancona area and was certainly felt throughout much of the Adriatic coast, although it did not produce damage as in the epicentral area.

Another clue to the effects of the Ancona earthquake in Atri is the commission in 1702 to Giovan Battista Gianni of the reconstruction, inside and out, of the church of santa Reparata. The rebuilding of the church of santa Francesco has been traced right back to Giovan Battista Gianni, a sculptor-architect originally from Cerano dIntelvi (Como) and documented in Abruzzo from 1685 to 1728. The presence of an artist of such distant origins should not come as a surprise: from the mid-15th to mid-18th centuries, in parallel with the period of highest seismic activity, Abruzzo was home to families of Lombard stone carvers (a term used to denote an area wider than Lombardy, also including eastern Piedmont and Canton Ticino) who maintained contacts with the land of dorigine and fostered a continuous influx of countrymen, becoming an important component of Abruzzo towns (several were the Confraternities of Lombards).

The earthquakes of 1703 and 1706 will then come to create a kind of artistic tripartition of theAbruzzo of the 1700s: while the mountainous part will look, by virtue of a series of economic, political and cultural relations, to Rome in the case of LAquila and to Naples in the case of Sulmona, the Adriatic valleys, peripheral to both theUrb and the capital of the Kingdom, will keep faithful to the masters of Lombardy, with whom communication was facilitated precisely by the coastal route that led to Bologna and from there up into the Po Valley. Obviously, this division should not be understood rigidly: to give an example, in 1727-1728 Gianni is called to Sulmona to decorate the church of the Santissima Annunziata. The new Franciscan church in Atri is reduced in length: the presbytery does not occupy the area of the old one, perhaps impossible to reuse because of the damage suffered and costly to tear down (in fact, today it looks like a ruin, with the perimeter walls but without the vault).

The façade occupies the same site as the previous one and assumes a pattern of inflected wings, a simplification of Borrominian models, which is an absolute architectural novelty for the region and which will be widely taken up in subsequent Abruzzi facades. Gianni is also responsible for the stuccoed slab above the central portal, with the Institution ofthe Pardon of Assisi. To mark the building’s importance in urban life, a sundial is placed on the tympanum, perhaps also present in the medieval church: in fact, until the Fascist era it will be the city’s only public clock (the tower of the Duomo marks the hours but has no dials).

The urbanistic centrality that the church had from its origins is enhanced by Baroque, especially Romanesque, scenographic devices: the facade is much higher than the original one and is connected to the Corso by a double flight of steps culminating in a sort of small square in front of the portal. The staircase, with its rather wavy lines, unique in Abruzzi architecture, can be seen as an extreme elaboration of the Tridentine instruction to build churches higher (but by a few steps) than street level. Lardito’s design was actually carried out much later, in 1776, by another Lombard (Ticino) architect, Carlo Fontana; until then, one went up to the church either by a simpler staircase or again by vico San Francesco. The main reference model is the staircase of Trinità dei Monti in Rome (Francesco de Sanctis, 1726), while the closest example in form, although with a more linear course than the Atrian staircase, is that of the church of the Santissimo Crocifisso in San Miniato (Pisa), by Antonio Maria Ferri (1718). The staircase sacrificed the space intended for stores, a sign of the economic decline that Atri had been experiencing since the mid-1500s; nevertheless, it confirmed itself as an urban spot frequented by society (cafes, promenades...) as well as a stage for sacred representations, such as the farewell of the Addolorata to the dead Christ in the Good Friday procession. Depots of nearby stores can still be found on the right side of the staircase, defiladed; the central loggia of the staircase, used as it is today to house a sacred image (so also in San Miniato), was not a store, contrary to assumptions.

|

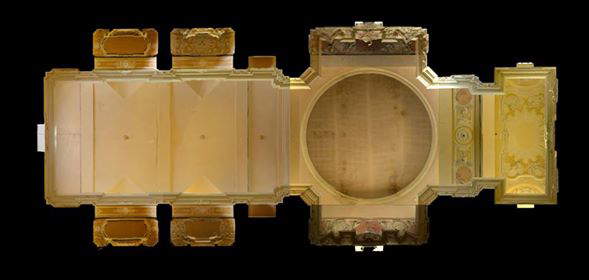

| The reliefs of the ceiling, left side and right side of the nave of the church of San Francesco in Atri (MD Technology images) |

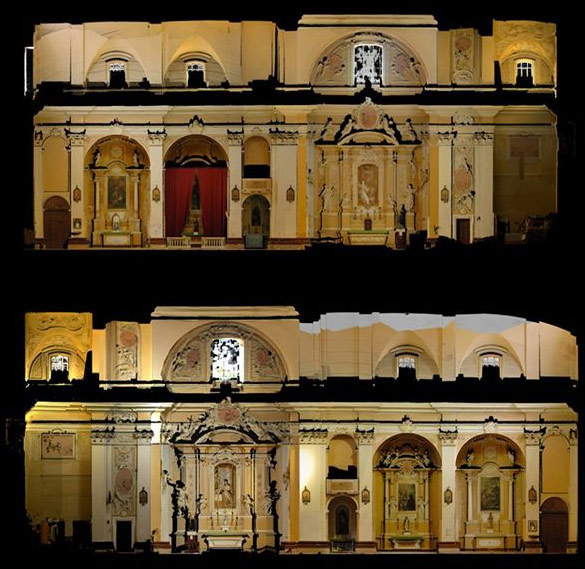

Inside, the structure is based on the typical Counter-Reformation church, with a single central nave, corresponding to the ancient one, framing the main altar; from what remained of the side aisles, three chapels on each side and a barely protruding transept were carved out, where the large chapels of St. Francis and St. Anthony of Padua were placed. The two chapels closest to the transept (the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Our Lady of Sorrows) were made somewhat lower and narrower than the others to insert the cornu Evangeli and cornu Epistulae pulpits and the transept pillars. The wooden truss ceiling, typical of Franciscan churches, was replaced with a hooked vault and, in the transept,with a hemispherical canopy.

Linterno focuses on the stuccoed decoration that particularly covers the chancel and side chapels. Little space is given to painting, probably by virtue of the greater expense incurred by the Franciscans for the sculptural and architectural part, the most scenic, although the spoliation suffered by the church due to the suppressions of 1809 and 1866 and clumsy restorations between the 19th and 20th centuries that plastered frescoed spaces on the vaults and walls of the chapels must be noted.

The canvases still present today are by local authors: the modest Giuseppe Prepositi probably painted, between 1770 and 1780, St. Raphael and Tobias and the Apparition ofthe Virgin to St. Gaetano for the chapels of the two saints; a century later, the altarpiece in the chapel of SantAnna, the Education ofthe Virgin, was made by Luciano Astolfi, who also frescoed the chapel of the Lady of Sorrows with two Angels holding the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (very badly damaged). Pertinent to the 18th-century period is the clothed statue of Our Lady of Sorrows. The large chapels of St. Francis and St. Anthony were designed from the beginning to also house stuccoed decorations pertaining to the two saints in the center, without any wooden statues or altarpieces. The chapels of the Immaculate Conception and Sacred Heart, on the other hand, now feature modern statues. The stuccoes are very similar in style and arrangement to those of the Santissima Annunziata in Sulmona (1728), an element that led to the suggestion that both decorations be assigned to Gianni.

|

| From left: the chapel of St. Francis (1715) and that of St. Anthony (1715) in the church of San Francesco in Atri (photo by Gino Di Paolo) and the altar of the transept of the Annunziata in Sulmona from 1728 (photo by Giovanni Lattanzi) |

|

| The Chapel of St. Anthony. Photo credit |

Although responding to similar reference schemes, of Austro-German origin and reinterpreted in the Lombard-ticinese valleys, one can see the stylistic evolution of Gianni: in Sulmona the structure and decorative party are more airy, light, freely revisited; in Atri, on the contrary, a more architectural and articulated conception prevails, in which the figures of the saints are much more solid and the floral decorations themselves are arranged in a rational manner. Just make a comparison between the transept altars in St. Francis in Atri (the large chapels of St. Francis and St. Anthony of Padua) and in the Annunziata in Sulmona. Or again, between a Sulmonese side altar and the chapel of St. Gaetano in the Atri church.

The church of St. Francis in Atri thus encompasses a complex historical and artistic story, which links it to phenomena affecting the entire culture of Abruzzo. It has been seven years, as mentioned above, that such a building has been closed to Atrians and visitors, in one of the busiest parts of the city. After the last earthquake, how many years must pass before it becomes a forgotten wreck?

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Gioele Scordella

Gioele Scordella è uno studente abruzzese di Storia dell'Arte all'Università di Firenze.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.