At the Uffizi, in the center of the “Hall of Dynasties,” stands one of the most famous portraits of the 16th century: the Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni de’ Medici, one of the greatest masterpieces by Bronzino (Agnolo Tori; Florence, 1503 - 1572). Eleonora, whose full name was Leonor Álvarez de Toledo y Osorio, was born in 1522, and was the daughter of Don Pedro Álvarez de Toledo y Zúñiga and María Osorio y Pimentel: her mother was the marquess of Villafranca del Bierzo, and her father, marquess consort, from 1532 until the year of his death, 1553, was viceroy of Naples, able to transform the city into one of the main centers of the Spanish empire. Eleonora was known throughout Italy, even as a young girl, for her extraordinary beauty, which we can well realize by observing, in her portraits, her sweet, oval face, her expressive brown eyes, and her noble bearing. In 1539, Eleonora had married Cosimo I de’ Medici, who only two years earlier had become Duke of Florence, and who in 1569 would become Grand Duke of Tuscany. At the time of the marriage they were very young: he was twenty, she seventeen. Legend has it that the two met and fell in love immediately, during an official visit of Cosimo to Naples. In reality, this was not the case: it is true that the two sincerely loved each other for life (a circumstance not so frequent in an era when arranged marriages were common among nobles), but the letters exchanged between Florence and Naples before the wedding tell us that the two were married without ever having seen each other. It was, however, a well-arranged marriage, since a true feeling was born between Cosimo and Eleonora, and their love was able to lead Eleonora to bear as many as eleven children.

In 1545, the year in which Bronzino, Cosimo’s court painter, painted the portrait now in the Uffizi, Eleonora was just twenty-three years old but had already borne Cosimo five children-Maria, Francesco, Isabella, Giovanni, and Lucrezia. Cosimo also had another daughter, illegitimate, born before his marriage to Eleonora: Bianca, known as Bia, an unfortunate child born to a mother whose identity we do not know, but whom Eleonora loved as if she were her own child, until her untimely death in 1542, when she was not yet five years old (another marvelous portrait of her remains, also painted by Bronzino and exhibited alongside that of Eleonora and Giovanni in the Uffizi).

Bronzino had become the Medici court painter because of his extraordinary talents as a portrait painter: Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives, speaking of the portraits of two Florentine nobles, Bartolomeo Panciatichi and his wife Lucrezia, had this to say that they were “so natural that they seem truly alive and that they lack nothing but spirit.” Vasari also mentions Eleonora’s portrait, writing that, after waiting for Cosimo’s portrait, also preserved in the Uffizi but spread in several replicas, “it did not go far that she portrayed, so as she liked it, another time the said lady Duchess, in various ways from the first, with Signor Don Giovanni his son following.” Proposing to identify the Uffizi portrait with the one mentioned by Vasari was art historian Luisa Becherucci in 1949: before then, various identifications were proposed for the child depicted in the painting, while today the idea that the son accompanying Eleonora is the second male is no longer in question. Bronzino’s spontaneous naturalness, coupled with the enviable mimetic qualities that enabled him to reproduce with great fidelity almost any material and the proverbial algid and detached appearance that his figures assumed, soon made him the most important, sought-after and sophisticated portrait painter in Medici Florence. According to Vasari, Cosimo I commissioned Bronzino to paint portraits of him and his wife after the painter had successfully completed the frescoes in Eleonora’s chapel in the Palazzo Vecchio, which were executed between 1541 and 1545: this is why, although there are no documents certifying the exact date of the Uffizi portrait, 1545 is thought to be the probable year of its completion. Moreover, a letter dated May 9, 1545, sent by Bronzino to Pier Francesco Riccio, Cosimo I’s butler, in which the artist asks for a larger quantity of lapis lazuli to be sent to him for the background of the painting, has been preserved: the work is not directly mentioned, but it is presumable that we are talking about the portrait now in the Uffizi. Finally, the date could also be indirectly confirmed by the identity of the child: in the past it was thought that it might be the eldest son Francesco, who, however, had much darker eyes than his brother’s, and unlike him had black, not brown, hair. It could not be one of the younger brothers either: the somatic features would not add up, and then it would be necessary to think of a portrait of an Eleanor over thirty-five years old, a rather advanced age for the time to think of including in the portrait references, as will be seen later, to the theme of fertility. Moreover, the connotations of the child’s face seem decidedly more compatible with those of Giovanni: the apparent age of about two years (Giovanni was born in 1543) would further allow the painting to be dated to 1545. Francesco actually appears in another portrait with his mother, that of 1549 now preserved in Pisa’s Palazzo Reale.

Bronzino, Portrait of

Bronzino, Portrait of Bronzino, Portrait of

Bronzino, Portrait of

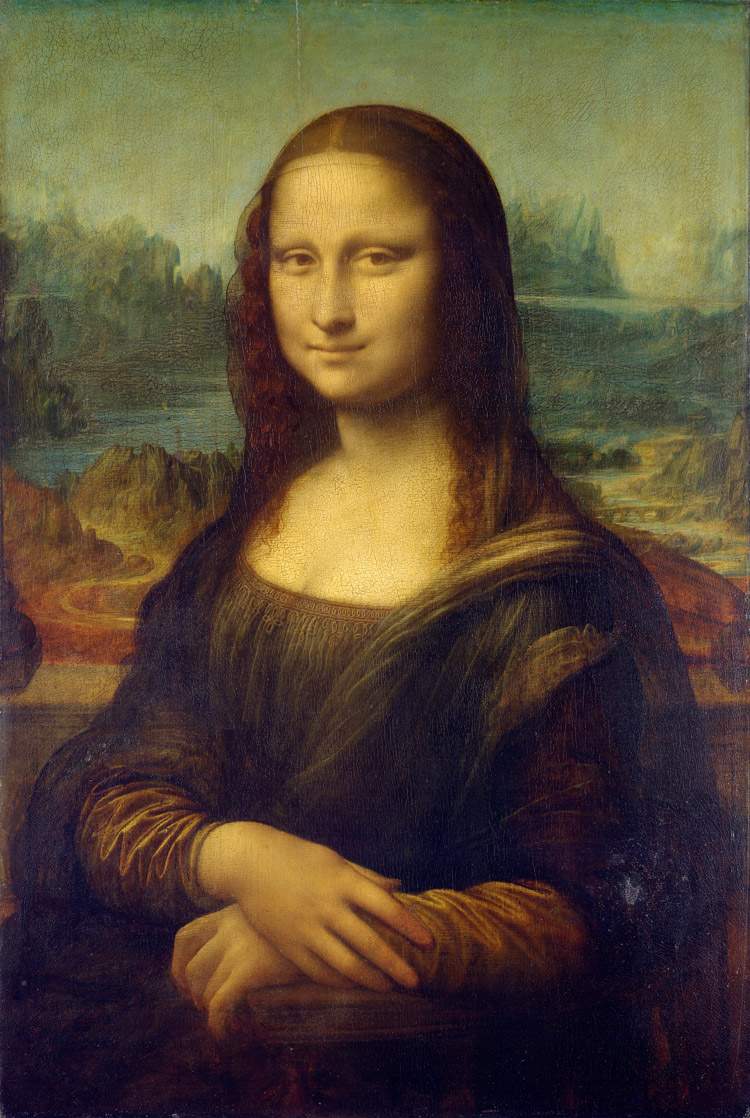

This is an image that had no precedent in the portraiture of Medici Florence. Eleonora is in fact depicted from the knees up, slightly turned three-quarters, seated on a red velvet cushion, leaning against the balustrade of a loggia open to a landscape. The pose recalls that of Titian’s Portrait of Isabella d’Este in Black, preserved at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, copies of which probably circulated in Florence around 1544-1545: Bronzino succeeds, however, in giving his Eleonora, characterized by an impassive expression, a more formal and distant look than that of Titian’s Isabella, although the love she always had for her children (and little Giovanni reciprocates, sketching a smile), and the pride of her character nevertheless shine through from her gaze. Other models from which Bronzino drew inspiration were probably Leonardo da Vinci ’s Mona Lisa and Raphael’s female portraits. Either way, Bronzino succeeded in producing an image that, scholar Gabrielle Langdon has written, was destined to be a “paradigm of European portraits of sovereigns and regents for centuries to come: formal in pose, stiffly but sumptuously dressed, detached in expression, and posed before a vast landscape.”

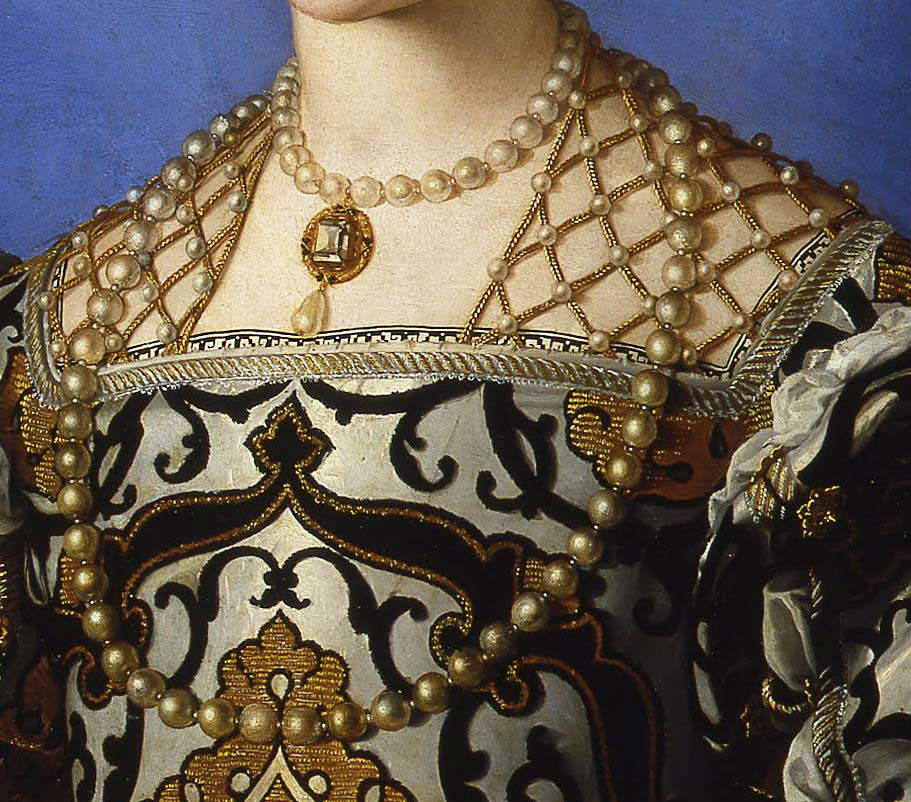

Eleanor is attired in the very famous damask brocade dress, decorated with elaborate black and gold motifs in terciopelo, a velvet typical of Spanish fashion that was woven in two distinct weaves, and reproducing pomegranates for the gold parts and arabesque motifs for the black parts, also typical of Moorish Spain. On her head she wears a gold and pearl net, typical of the Spanish fashion of the time that the duchess had introduced in Florence, while on her ears she sports two drop pearl earrings. Again, around her neck she wears two pearl necklaces, one of which has a diamond and pearl pendant, and at her waist she wears a gold belt, set with precious gems and ending in a beaded tassel. Underneath the rich robe, however, she wears a linen shirt, which we can see peeking out at her wrists and across her chest (we see the embroidered border, in the same pattern as the cuffs, under the net of pearls covering Eleanor’s shoulders). Little John is also wearing a luxurious blue taffeta dress woven in gold, and like his mother he turns his gaze to the observer. Eleanor is caught touching John’s shoulder: the gesture indicates protection toward the second son, chosen in place of the first-born son since the latter, according to the mentality of the time, even more than the former guaranteed continuity to the dynasty, since he was seen as a kind of insurance if something happened to the first-born. And it is precisely dynastic continuity that John’s presence is meant to symbolically allude to. Behind the duchess, we can then observe a landscape under a dark, almost leaden sky, a nocturnal setting, although Eleanor and Giovanni appear illuminated as if daylight were projected on them, highlighting every single detail of the dress.

It is necessary, meanwhile, to dispel a myth about this portrait, and in particular about the dress. Indeed, in the portrait we do not see the dress in which Eleanor was buried, despite the fact that the legend continues to circulate: the belief spread starting in 1888, when Marquis Guido Sommi Picenardi first published the account of the exhumation of Eleanor of Toledo’s body performed some thirty years earlier, in 1857. In Sommi Picenardi’s text it could be read that “the rich robes, fashioned according to the middle of the 16th century, and plus some braids of hair of a blond color tending to red, attorted by a cord of gold and similar in all respects to those painted by Bronzino in the portrait of this Princess, preserved in the R. Galleria degli Uffizi, posed certainty to establish the identity of the corpse.” The robe was described as “not a little torn” and “of white satin, long to the ground and richly embroidered in chevron pattern in the bust, along the petticoat and in the foot flounce.” It was long thought that the adjective “similar” used by Sommi Picenardi was sufficient to assume that the dress found in Eleonora’s tomb was the one painted by Bronzino: in fact, the dress, recovered after a second exhumation between 1945 and 1949 and kept in the Bargello’s storerooms, was then restored in the late 1980s, with an intervention that ruled out the possibility of identifying the dress with the one in the painting. It is much more likely that that sumptuous dress is nothing more than an invention of Bronzino’s: the artist, in fact, did not work by portraying the duchess from life, although the attention to detail might lead us to think so. For the face, Bronzino probably made use of a few schematic sketches drawn quickly, while for the dress the painter followed his classic modus operandi: he had samples of dresses sent to him, which he then used to imagine the clothes that would end up in his paintings. And since the Medici registers preserved in the Florence State Archives carefully describe the family’s clothes, but there is no description that matches the dress worn by Eleonora in this painting, the idea is that this sumptuous dress is the result of Bronzino’s original imagination.

It was, however, undoubtedly a dress that perfectly reflected Eleanor’s taste. It was probably she, after all, who chose the clothes for herself, her husband and numerous children, continually giving work to the court tailor, Agostino da Gubbio. And in the case of the portrait, there is no doubt that the dress should express her status as the wife of a ruler. The fabric, meanwhile: brocade was valuable, and reproducing it with the exactness demonstrated by Bronzino necessarily took time. It follows that Eleonora’s attire is the most appropriate for a state portrait, and the relevance of this painting is also attested by its numerous derivations, for example the one painted by Lorenzo della Sciorina in which another son, Garzia, appears in place of Giovanni, or Bronzino’s autograph replica preserved at the Detroit Institute of Arts. The preciousness of the dress is then complemented by symbolism, beginning with the pomegranate, associated with marriage and fertility. The silk of the dress itself was probably meant to signify, politically, the flourishing state of the Florentine textile industry, which precisely in the early years of Cosimo I’s rule had regained vigor. Instead, the dominant colors hark back to Eleonora’s lineage and that of her husband: first and foremost, blue (that of the sky and of John’s dress) and white of the dress prevail: blue and white were the heraldic colors of the Álvarez de Toledo family. Conversely, gold (that of the decorations) and red (the pillow) are the heraldic colors of the Medici. Finally, the high degree of illusionism is aimed at arousing awe in the viewer, just as the distant figure should inspire in the relative a sense of respect, of deference.

And then, three elements contribute to making the figure of Eleanor almost hieratic: the general appearance of the painting, which recalls that of the Madonnas with Child; the blue background executed with lapis lazuli, the most expensive of pigments, usually used to paint the Virgin’s mantle in sacred paintings; and the faint halo of light that we discern around Eleanor’s head, almost as if her head were surrounded by a halo. “Eleanor’s dress,” Langdon writes again, “affirms her rank and marks [...] her rising above ordinary human beings.” Eleonora was not particularly liked by the Florentines, who ill tolerated her stern attitude, probably perceived as haughty. In reality, hers was a behavior in line with the customs of Spanish nobles: she was rarely seen in public, when she went out she was always surrounded by guards and servants, plus she always preferred Spanish to Italian, which she did not speak well. Moreover, she took very little interest in politics. However, the Florentines knew very well that she was a woman of virtue: and so her image must recall that of the Madonna. Even the expedient of illuminating the figure by daylight, despite the nocturnal setting, perhaps has something to do with the intention of presenting Eleonora as a supernatural creature. Bronzino, who also wrote poetry and was well acquainted with Petrarch’s work, surely kept in mind Petrarch’s verses, “Vergine bella, che di sol vestita, / coronata di stelle, al sommo Sole / piacesti sí, che ’n te Sua luce ascose, / amor mi spinge a dir di te parole.” And also contributing to this sacred aura surrounding the figure of Eleanor is a commentator of the time, Antonfrancesco Cirni, who, writing about the Royal Entry of Cosimo and Eleanor in 1560 in Siena after the conquest of the city by Florence, affirmed that Eleanor “appeared more than earthly queen of most honest beauty, and of beautiful honesty all sprinkled with gratia realità goodness, maestà sopr’humana dressed in white velvet embroidered with gold carved with a head of precious gems such as diamonds, rubies, smiralds with vezzi of pearls, and girded full of jewels, with a sable around her neck, so that they were worth from three hundred thousand scudi.” Moreover, the figure quoted by Cirni is certainly exaggerated (to offer a term of comparison it will suffice to consider that, in 1559, all of Cosimo and Eleonora’s court staff, that is, more than three hundred people, had cost 24,000 scudi for the entire year, and salaries were not considered low), but it still gives an idea of the value that was attributed to the duchess’s ornaments.

Detail of the

Detail of the

The strong symbolic bearing of the portrait is also conveyed by the jewelry. Eleanor’s passion for pearls is immediately apparent. Benvenuto Cellini, in his Vita, recounts a curious episode (to which, of course, it will be necessary to make all the necessary adjustments, since Cellini certainly did not go down in history for being a reliable narrator): the duchess went to the great artist, author of the Perseus, to have him appraise a string of pearls, for which the seller was asking a very high figure. Cellini responded by saying that those pearls were worth very little, but Eleonora wanted them at all costs and asked Cellini to go to Cosimo, who was supposed to buy them for his wife, and tell him that the purchase was worth it. Disgruntled, Cellini went along with the duchess, but Cosimo immediately sensed that what was being proposed to him was not really that “beautiful vezzo of pearls, most rare and truly worthy of Your Most Illustrious Excellency” that the artist was extolling to him, and he wanted to know the truth from Cellini, because he could not believe that a goldsmith of his caliber would recommend buying those pearls at such a reckless price. He then responded by saying that if he told the truth, he would antagonize the duchess. Cosimo understood his wife’s plot, however, instead of protecting the artist he affirmed before Eleonora that “my Benvenuto told me, that if I buy it, that I will throw away li mia dinari.” In the end, Eleonora nonetheless found a way to procure the string of pearls, and gave orders to kick Cellini out of the palace whenever he showed up, while Cosimo arranged instead to welcome him: thus, the poor goldsmith was either received or turned away depending on who was present in the house. The comical episode, besides testifying to the stubborn character of the duchess, reveals how much she loved pearls. And in the portrait she wears them almost everywhere, not least because they were a symbol of purity (associated with the color white, and furthermore pearls preserve their purity as they cannot be carved or altered), as well as of chastity: in ancient times it was in fact believed that they were born from shells fertilized by divine intervention.

Eleanor wears pearls on her head, in the Spanish-style net of golden threads, and on her ears, with the two earrings from which drop pearls hang. One curious element can be noted: Eleonora has pierced ears. As art historian Silvia Malaguzzi explained, until shortly before the portrait was executed, pierced lobes would have been considered disreputable and unbecoming for a noblewoman. This lady’s jewelry was in fact of very recent introduction: still in 1525, the Venetian chronicler Marin Sanudo could report in his Diaries that, having been invited to a wedding of the Venetian high society, he saw among the guests a “siora Marina, fia de Filippo Sanudo, mia parente, et muier de Zuane Foscari la qual se ha fato forar le recchie, et con un aneleto de oro sotil portava una perla grossa per banda,” stating that “hera costume de le more de l’Africa et mi dispiacque assai.” In addition to being typical of African women, at that time pierced ears, Silvia Malaguzzi further explains, were associated with sailors, who had their lobes pierced to signal to fellow sailors that they were willing to take special care during long sailings. Furthermore, Deuteronomy (15:12-17) says that if a slave professes an act of loving submission to his master (“for he loves you and your house and is well with you”), the master, to seal the servant’s dedication, will be required to symbolically pierce his ear. It is therefore likely that the transition of this practice to women’s fashion acquires an additional symbolic meaning, that of the wife’s dedication to her husband, amounting to a declaration by the woman to preserve, moreover, her vow of chastity, since the piercing of the lobe was a symbol of a promise that had to be honored.

Going down, here are the two pearl necklaces, one of them a probable wedding gift from Cosimo: it is the one with the diamond, a Medici symbol that alludes to the strength of the family, being a stone resistant to shocks and fire. Still further down, here is the belt: it has been thought that it might have been designed by Cellini, who again in his Vita wrote that Eleonora “requested him that I make her a gold belt; and this work also very richly, with jewels and with many pleasant invention of masks and other things: this she made.” In the belt depicted by Bronzino, the “mascherettes” Cellini mentions do not appear, but the jewel we see in the painting is probably very similar to the one the artist actually made for the duchess. The belt did not serve to tighten the robe, it had only an ornamental function, and here it also rises to a symbolic role. Meanwhile, it was traditional for the belt to be fastened by the bride’s father on the wedding day and unfastened by the new husband on the wedding night: it was thus both a symbol of preserved chastity and a marital symbol. In addition, we note that it is decorated with three types of gems: diamond, balascio (a stone similar to ruby but of a less intense red) and emerald, the latter worked in cabochon, or dome shape. Malaguzzi proposed identifying in the three colors (white, red and green) the symbols of faith, charity and hope, and at a second level of interpretation those of nobility, loving-kindness and fertility (the emerald was in fact a gemstone dear to Venus). Finally, a final hint of the fertility theme is inferred by absence: indeed, we note that Eleanor, despite being married, does not wear a wedding ring on her finger. There is a portrait in which the duchess wears a wedding ring: it is preserved at the Národní Galerie in Prague, and the jewel we observe is the gold one with a diamond cut at the table that was given to her by Cosimo when the couple married, and to which the duchess was very fond (she was also buried with that ring). In the Uffizi portrait, the duchess wears no ring because the emphasis of the portrait is not on the love between her and Cosimo: the focus on which Bronzino concentrates is broader and concerns on the one hand Eleonora and her virtues of chastity and fertility, which moreover respond to her motto Cum pudore laeta foecunditas, and on the other hand the dynasty as a whole, and it is also for this reason that the role of Giovanni is insisted on.

Finally, the landscape, a fundamental element of the painting, both for its allegorical bearing and its political significance, deserves mention. We see a landscape where rivers abound: water, according to Neoplatonic doctrine, particularly Ficinian, still prevalent in Florence at the time of Cosimo I, was a symbol of generative power. Earth alluded to femininity, fire was the fertilizing element, and air the one that nourishes life and sustains it (John’s presence alludes to life). Fire, the masculine element, is to be found in Cosimo’s armor, in the official portrait the duke commissioned from Bronzino shortly before that of his wife. As for the political significance, the landscape has been interpreted as that around the Medici Villa at Poggio a Caiano, the residence built by Lorenzo the Magnificent, where Giovanni himself was born, and where Eleonora had spent a large part of her pregnancy. Read in this way, the landscape would thus take on a further implication related to the dynastic continuity of the Medici, with reference to the past as well. Scholar Bruce Edelstein, however, has suggested identifying the landscape in that around Pisa, where some of the Medici’s most lucrative territories were located (so much so that there is preserved, in a private U.S. collection, a portrait from about 1546, by an unknown hand, in which Cosimo and Eleonora are depicted together consulting a map of Pisa). It is precisely the presence of water that may allude to the important reclamation operations of the marshes around Pisa undertaken under Cosimo’s rule.

An official portrait, an image with many symbolic values, an unmistakable display of Medici power, a most eloquent testimony to the court’s taste, the portrait of Eleonora executed by Bronzino is this, but not only: “Eleonora,” wrote Antonio Paolucci, “is also the beautiful, wise woman, in love with her husband and beloved by her husband, the tender and affectionate mother of whom the chronicles speak.” An important scholar of the early seventeenth century, Cristoforo Bronzini, author of a work Della dignità e nobiltà delle donne, described Eleonora as a “serenissima signora” who had “l’andar grave, lo stare reverendo, il parlar dolce, pieno di sapere, la faccia chiara, la vista angelica e tutte le altre bellezze che si leggono essere state nelle più celebri donne.” Qualities that had not escaped the painter’s notice: and so, despite what Paolucci calls the “protocollar rigor of the state portrait,” Bronzino’s greatness also lies in having brought out “the character of the woman, as it emerges from the words of the contemporary chronicler.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.