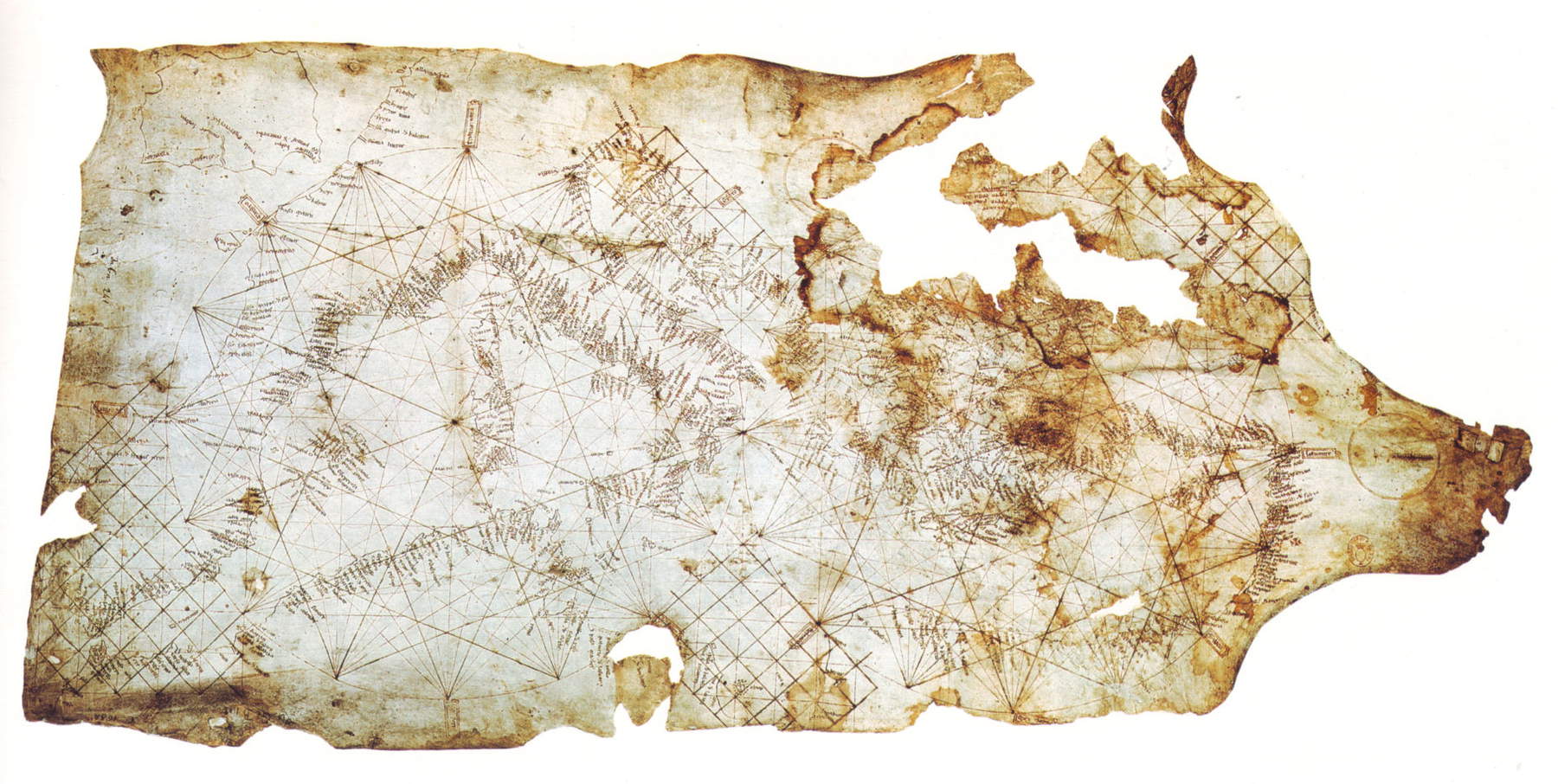

In the panorama of medieval cartography, the birth of the firstportulan chart of the Mediterranean marked a momentous turning point in the way geographic space was conceived and represented, and between the 13th and 14th centuries, a new tool made its appearance in the hands of European mariners: the portulan chart. This is a profoundly different product than a simple evolution of the Ptolemaic maps already in use. But what do we mean, first of all, by the term Ptolemaic map? Ptolemy’s planisphere is a representation of the world as it was thought to be known and depicted in the second century CE by the West. The map is based on descriptions in the Geographia of the Egyptian geographer and astrologer Claudius Ptolemy, a work compiled around 150 AD. Although no original maps have ever come down to us, the text of the Geographia has thousands of geographic references accompanied by coordinates, thanks to which cartographers, after the rediscovery of the manuscript around 1300, were able to reconstruct the worldview represented by the author.

Well, the portolan chart is quite different: in fact, it is based on empirical observation and the practical knowledge of sailors. Unlike medieval mappae mundi, which had a symbolic and theological function, portolan maps were practical tools, intended foreveryday use by sailors. Coastlines are drawn in great detail, and ports, inlets, and useful navigational landmarks are highlighted. The interior of the continents, however, is often left blank or occupied by marginal decorations. The focus of the representation is thus the sea, crisscrossed by a dense network of lines indicating the main routes according to the winds of the 32-point rose.

Thus, nautical charts reflected the geographical knowledge of the time and were practical aids to navigation, particularly with the spread of the compass between the 12th and 13th centuries. The reference grid was based on a radiocentric wind rose, with sixteen major points and as many minor roses arranged around it. The rhombuses drawn from each rose indicated the directions of the winds, in black for main winds, green for intermediate winds, and red for minor winds. The charts did not include any geometric projections: meridians and parallels were not considered because this was navigation that we could call flat. What does this mean? Simply that the earth’s sphericity was ignored.

This includes the creation of the oldest nautical map of the Mediterranean that has come down to us in its entirety: the Pisan Map, dating from the late 13th century and currently housed at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris. It is in fact an anonymous work attributed with certainty to the Genoese milieu, which, in addition to its high graphic accuracy, is especially striking for the abundance of place names along the coast, a feature that will be preserved almost unchanged even in the charts of the 14th century. The richness of the coastline is contrasted by the almost total absence of names in the inland areas.

The Tyrrhenian side of the map, particularly the Calabrian section, has a higher toponymic density than the Ionian, a clear sign of the lesser importance of the ports on the Ionian. At the same time, the distribution confirms the Genoese origin of the map, as it reflects the familiarity of the Republic of Genoa with the Tyrrhenian basin, over which it exercised a more pronounced dominance.

TheCharter shows routes based on cardinal winds, distances and a precise scale, features that make it one of the earliest cartographic representations made to scale since ancient times. We also know that maps predating the Pisan Map, such as Greco-Roman astronomical maps, were not designed for navigation and were completely unknown in medieval Europe. Moreover, the use of rulers and compasses (also called dividers) was essential in both the making and interpretation of the map, which required at least an elementary knowledge of arithmetic. Thus, the entire Mediterranean and the Atlantic up to Cape St. Vincent is represented in the Pisan chart. Later, as Italian navigation became more interested in the north, all charts expanded to include with greater accuracy the English Channel, Flanders, the North Sea, and parts of Scotland.

The chart’s eight-pointed wind rose was later expanded to a division into sixty-four directions. The names of the eight main winds were retained in Italian, while combinations derived from them were used for the additional fifty-six directions.

During the 14th century, the figure of Petrus Vesconte, a Genoese cartographer active in Venice, marked a considerable evolution in cartographic production, making it more articulate and technically advanced. He is the first known author to sign his own maps and to introduce important innovations, such as the modular representation of coastlines and the systematic use of the wind rose and course lines. He is also credited with the oldest dated nautical charts known to date.

The first, made in 1311 and now preserved at theState Archives in Florence, bears the inscription Petrus Vesconte de Janua fecit ista carta anno domini MCCCXI and depicts the eastern Mediterranean. Two years later, in 1313, he produced an atlas consisting of six charts covering the entire Mediterranean basin and the Atlantic coasts of Europe as far as the British Isles and Holland. Between 1313 and 1320 he produced four more similar atlases, all dated from Venice, the city where he operated at least in the final phase of his career and where he most likely helped introduce or perfect the art of nautical cartography.

Vesconte is also credited with the charts appended to Marin Sanudo’s Liber secretorum fidelium Crucis, a work of which there are about ten known codices, including a planisphere of particular note. The identification with a Perrinus Vesconte, author of maps dated between 1321 and 1327, which could correspond to the same person or to a distinct cartographer, remains uncertain.

During the 15th century then, the tradition inaugurated by Vesconte continued and was strengthened with new figures. Grazioso Benincasa, a native of Ancona and member of a noble family, was the most active and well-known Italian cartographer of the century. Born around 1400, he was in all likelihood also an expert navigator, accustomed to traversing the Mediterranean and accurately recording all the information useful for running a ship. His earliest work, a portolano (a navigation manual) devoid of charts but rich in coastal descriptions, covers the eastern shores of the Adriatic to the Black Sea. Although incomplete, the text, now preserved in manuscript in the Ancona Municipal Library, is particularly important because of the value of the personal observations it contains. The dates given in the manuscript indicate a redaction between 1435 and 1445.

Benincasa also made numerous nautical charts and atlases, about twenty-five of them known, produced later than the pilot book: the earliest dated document is dated 1461, now in theState Archives of Florence, while the last is dated 1482, preserved in the University Library of Bologna; some specimens bear no date. He drew his maps both in his hometown and in Genoa and Venice. Active for at least fifty years, Benincasa was a major contributor to the nautical cartography of the time. His maps stand out for their originality and offer valuable insight into the geographical outlook prevalent among Italian navigators on the eve of the great discoveries.

Returning to nautical charts, cartographic historian Tony Campbell, author of the 1987 chapter Portolan Charts from the Late Thirteenth Century to 1500 in the first volume of The History of Cartography, a volume edited by J. B. Harley and David Woodward, indicates that charts were not constructed on the basis of geometric projections, but through direct measurements of course and distance collected by generations of navigators. Their spread coincides with the period of maximum development of trade routes in the Mediterranean. Genoa, Venice, Pisa, Barcelona, Marseilles: the great maritime powers equipped themselves with cartographic workshops and commissioned increasingly complex atlases. The nautical chart thus became not only a technical tool but also a strategic asset, to be protected and transmitted with care.

In material terms, charts were instead made on sheep’s vellum, an expensive medium but resistant to moisture and handling. The ink used varied according to function: black for coastlines, red for important place names, and gold or blue for decorative elements. Port names were written in the cartographer’s vernacular language, but there was no lack of linguistic contamination reflecting the cosmopolitanism of the seas.

The first portolan charts thus represent a turning point in the history of cartography. No other map, in their own time, succeeded in rendering the geographical contours of the Mediterranean with equal fidelity. Even in the earliest surviving specimens, the shape of the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins is strikingly close to reality, a result that contrasts sharply with the symbolic and distorted representations of coeval maps, such as the HerefordMap, painted around 1300 by Richard of Haldingham.

Beyond that, the maps are most notable for their direct connection to the concrete world. They were intended to meet practical needs, particularly those of navigators. Intended for skilled hands and sea voyages, they were instruments designed for orientation, calculating distances, and following routes. Elements such as the compass and scale, rarely found in maps designed for scholars or courts, became indispensable here. Commerce, more than theory, guided the cartographers’ hand.

Already remarkable for accuracy from the earliest versions, portolan charts continued to be refined: new coastal locations were inserted, names updated, routes adapted. As long as they retained their practical function, they continued to improve. But with the loss of their centrality in the world of navigation, beginning in the second half of the sixteenth century, a gradual decline can be observed, both in the accuracy of outlines and in the quality of place names.

In any case, the charts also had another fundamental merit: they were among the few to graphically document the explorations that preceded and accompanied the Renaissance. At a time when the geography of the world was changing rapidly, the portolan charts presented a concrete and up-to-date reference. They were not objects intended for luxury or celebration. As everyday tools, they served and then disappeared. Yet in their operation, they made essential contributions to medieval life. And if some still shine today for their illuminated decorations, the real legacy lies in the extraordinary formal consistency maintained by the simpler ones, which for more than two centuries have been able to hand down, almost intact, the faithful image of the known coasts.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.