The Jewish origins of the German artist Otto Freundlich (Słupsk, 1878 - Majdanek, 1943) constituted in itself a cause for condemnation and persecution by the Nazi regime, but his ideas totally opposed to the regime gave further cause. On the occasion of the first international postwar exhibition, held in Düsseldorf in 1922, critics loyal to the future regime lashed out against the show with arguments with defamatory features, due to the presence ofJewish-French art, which they considered to be the result of Jewish-Dadaist madness, and already in that case Freundlich was qualified as Jewish-Bolshevik, since he would have contributed, through his idea of art, to “contaminating it with red,” that is, to express through his works principles close to communist, and more specifically Marxist, ideology.

Freundlich was deeply convinced of the necessity of the creation of a new man, or rather, of the real need for a different man, capable of giving birth to a new society: the individual was, in his view, to be extremely connected to the world of experience, but the five senses were to have the purpose of transcending the conventional limit of things. In this way, man and his surroundings would interact with each other, as would spirit and matter. Ethics would govern these processes, so his idea of society was based on the abolition of boundaries between world and universe, between individuals, and generally between all perceived things.

Underlying the change of the individual, in order to bring about a new society governed by the assumptions listed so far, was art, so art and life had to be, according to Freundlich, inseparable. These principles were shared, beginning in 1918, by the Novembergruppe, an association of artists linked to the avant-garde, which had been formed in Berlin in December of that year: in fact, the name was derived from the so-called November Revolution, which broke out at the end of World War I. The group’s main founders (it included Max Pechstein, Rudolf Belling, Erich Mendelsohn, Georg Tappert, among others) started theArbeitsrat für Kunst, the Workers’ Council for Art, to which painters, sculptors, and architects, including Otto Freundlich, belonged. These proposed a national artistic renewal through a close relationship between artists and the public. The group was disbanded in 1929, but many of its members blossomed into the Bauhaus, a school of art and design founded by Walter Gropius (Berlin, 1883 - Boston, 1969), who unsuccessfully tried to give Freundlich a professorship as professor of sculpture in 1922.

|

| August Sander, Portrait of Otto Freundlich (ca. 1925; silver gelatin photograph on paper, 26 x 18 cm; London, Tate Modern) |

Facing censorship by the Nazi regime and opposing the closure of the Bauhaus, the artist wrote in 1933 the text Für das Bauhaus und gegen die Kulturreaktion, where he expressed the ideal of the pioneer of the new art and architecture against the ideologies of the regime, mentioning architect and racial theorist Paul Schultze-Naumburg (Naumburg, 1869 - Jena, 1949) among the exponents of art close to Nazism.

“No Schultze-Naumburg and no Hitler will make it impossible; they cannot kill the spirit because it has already conquered the world and is conquering new cities in Soviet Russia [...]. We know our enemies and we ask nothing of them. The new race we intend does not know the color of their skin and hair; they will be there when they get rid of the powers of the government they want to abuse,” the artist wrote. And two years later he wrote Zur Nationalisierung des Gaistes, an appeal against nationalism.

In addition to his ideology, the regime did not toleratehis art’s rapprochement withthe avant-garde movements, with which Freundlich had come into contact in Paris and Berlin: in the French capital, the artist became acquainted with the Montmartre milieu and Pablo Picasso (Malaga, 1881 - Mougins, 1973) and, after a brief stay in Berlin where he approached the Berliner Secession far from the art of the academies, he returned to Paris to make his first abstract compositions. Among them is the composition made in 1911 and now preserved at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris: it is a work contemporary to the founding paintings of abstract painting, thus to artists such as Vasily Kandinsky (Moscow, 1866 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1944) or Robert Delaunay (Paris, 1885 - Montpellier, 1941), but which testifies to the transition from expressionism to the first phase of abstractionism. Starting from the observation of nature, the curve becomes in the artist “the element that gives rise to the corporeal, to the three-dimensional; the arm that shows a direction, the symbol of our connection with the universe.” In Paris he had the opportunity to meet Constantin Brâncuşi (Peştişani, 1876 - Paris, 1957), Amedeo Modigliani (Livorno, 1884 - Paris, 1920), Georges Braque (Argenteuil, 1882 - Paris, 1963), Juan Gris (Madrid, 1887 - Boulogne-sur-Seine, 1927); before the war, however, he came into contact with the Dada movement in Berlin.

|

| Otto Freundlich, Composition (1911; oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm; Paris, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville) |

In this context of great artistic and cultural ferment, Freundlich created in 1912 the sculpture entitled Big Head: this was in fact a large face typical ofprimitive art that was inspired by the huge statues on Easter Island; it entered the collections of the Museumfür Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg. But the story of this work did not end there.

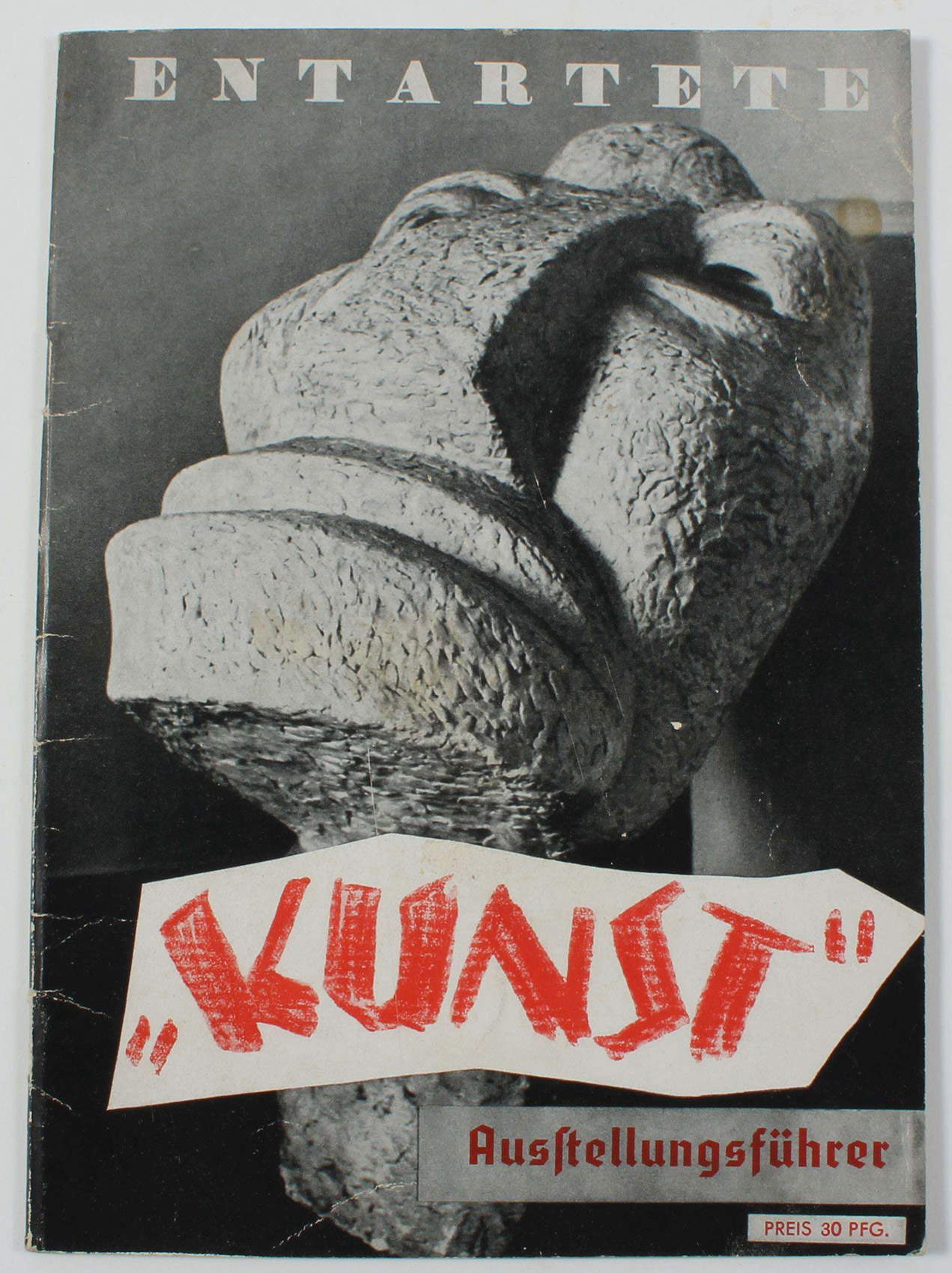

In July 1937 an exhibition entitled Entartete Kunst, in Italian Degenerate Art, curated by Adolf Ziegler (Bremen, 1892 - Varnhalt, 1959) was mounted in Munich at theHofgarten Institute of Archaeology. The latter was an artist of the Nazi regime who headed the Reich Chamber for the Visual Arts, with the aim of popularizing the regime’s German art. Through art the idea of race was spread better than through words; it was to serve as an example. At the same time, however, art had spread, in his view, that had caused degradation, the weakening of morals: hence the definition of “degenerate art,” guilty of deviating from the true purpose of art, and as such was to be repressed. It was for this reason that one of the most significant ideologues of the totalitarian defense of art, Wolfgang Willrich (Göttingen, 1897 - 1948), wrote in 1937 a pamphlet, Säuberung des Kunsttempels, meaning “Cleansing of the temple of art,” according to which it was necessary to withdraw from German museums all works belonging to degenerate art. It was Willrich himself who called Freundlich a Bolshevik as an artist who had contributed to the “red” contamination of art, its Bolshevization.

|

| Otto Freundlich, Der neue Mensch (1912; plaster; formerly in Hamburg, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe; now missing, probably destroyed during the Nazi regime) |

|

| Cover of the catalog of the exhibition Entartete Kunst |

Returning to the Entartete Kunst exhibition, the symbol of the latter became precisely the Great Freundlich Head, since an image of the sculpture had been reproduced on the cover of the exhibition catalog, to which, however, the title had been changed to Der neue Mensch, or The New Man, recalling in a negative sense the theories underlying the art and society of the author of the work depicted. The sculpture was derided by many artists and critics, both because of its author’s Jewish origins and because of the facial features depicted. In keeping with the “cleanliness of art” mentioned above, fourteen of Freundlich’s works that had entered the collections of German public museums were seized; among them, of course, was the Great Head, which was probably destroyed by the Nazis. It was never found again.Racial hatred led to theelimination and destruction of many works of art, of which there is therefore no trace left today except the tale of a painful affair. There is, however, a fact to be added to reflect on: of this great sculpture it is possible to tell the story, since it is significant and well-known, making it still possible to view it through photographs and documents, but of so many other works, whose history is less relevant or little known, traces have been completely lost forever.

One of the artist’s works to have been miraculously spared is the mosaic entitled Die Geburt des Menschen, translated The Birth of Men, executed in 1919. It is a central work in Freundlich’s production because it closes his early, still figurative path and anticipates abstractionism: indeed, one can see a coordinated rhythm of vivid colors and a continuous relationship between the complete work and the detail, an aspect that attests to the mutual connection between man and the world, the focus of his thought. The mosaic was originally intended for the villa of tobacco merchant Josef Feinhals in Marienburg, a district of Cologne, but was never placed there; in 1954 it was donated to the city and installed in the lobby of the Cologne Opera House. A recent exhibition held in 2017 in the city’s Museum Ludwig presented it as a major feature.

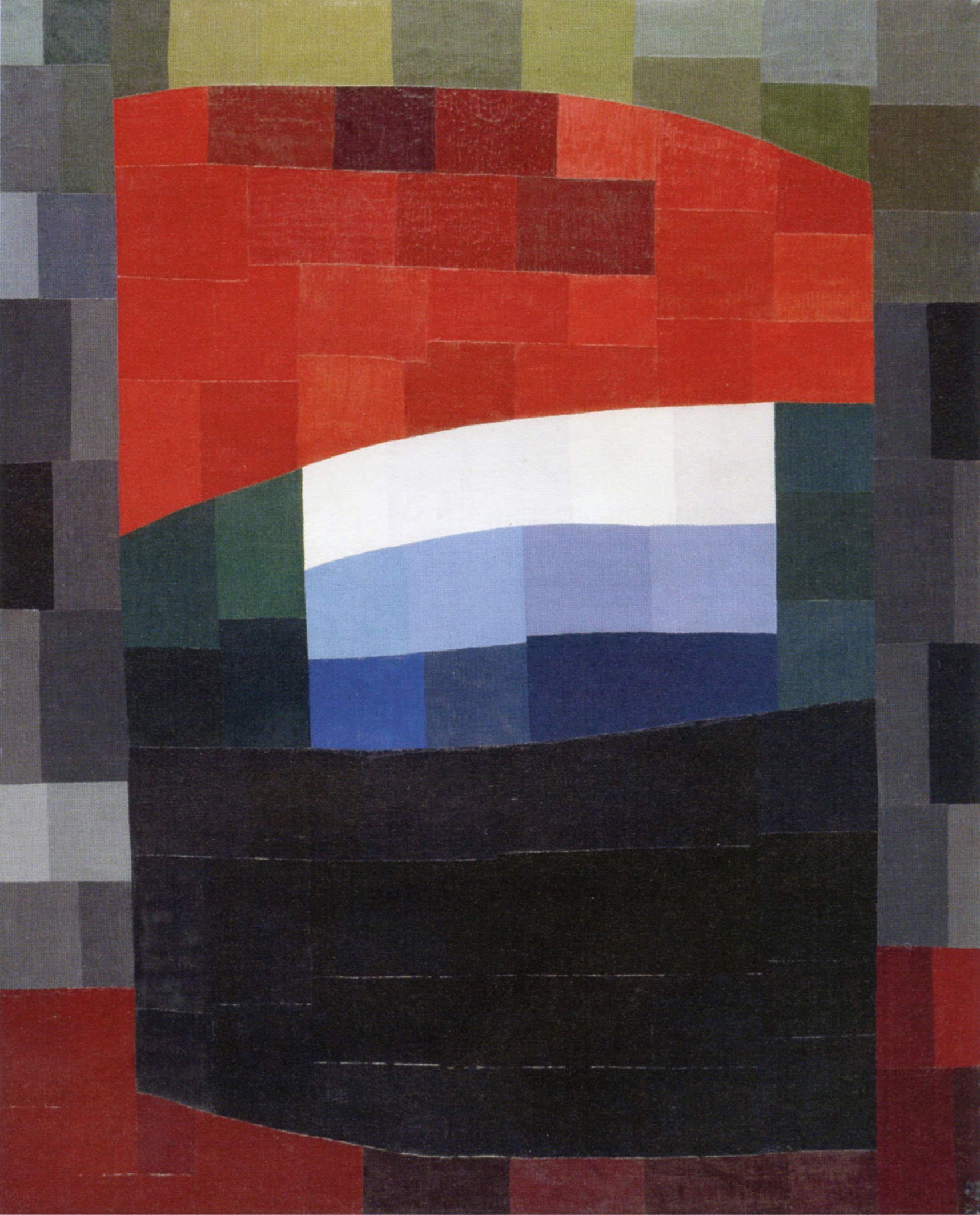

To the mosaic can be added the canvas Mein Himmel ist rot ( “My Sky is Red”), which right from its title contains a political statement on the part of the artist and was created through juxtapositions of juxtaposed color boxes, imitating the mosaic technique. Painted in Paris in 1933 and exhibited that same year at the Salon des Indépendants, it was donated in 1953 to the French state by Jeanne Kosnick-Kloss, Otto Freundlich’s partner.

|

| Otto Freundlich, Die Geburt des Menschen (1919; mosaic, 215 x 305 cm; Cologne, Opera House) |

|

| Otto Freundlich, Mein Himmel ist rot (1933; oil on canvas, 162 x 130.5 cm; Paris, Musée d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou) |

The Nazi regime did not, as we know, only turn on art, but especially on people: from September 1939 to June 1940 Freundlich was interned in five camps. During this period the artist wrote numerous letters to his beloved Jeanne, expressing his concern for his art. He was released and managed to take refuge in Saint-Paul-de-Fenouillet and then in Saint-Martin-de-Fenouillet in the Eastern Pyrenees. He was joined by his Jeanne. In the course of a roundup, following a tip-off, Freundlich was arrested and taken to Drancy; from there he was deported to Majdanek concentration camp, where he was probably killed on March 9, 1943.

The killing of Otto Freundlich bears witness to one of the countless murders carried out by the Nazi regime against Jews and all those who in any way opposed the system. And it is tragic to think that the sole purpose of all this was “race cleansing” for the supremacy of the pure German race. This is a reflection that should accompany us not only on Memorial Day, but should be firmly in our minds to counter all expressions of racial hatred.

Reference bibliography

Uwe Fleckner (ed.), Das verfemte Meisterwerk: Schicksalswege moderner Kunst im Dritten Reich, Walter de Gruyter, 2012

Geneviève Debien, Otto Freundlich (1878-1943) entre 1937 et 1943: un artiste classé "dégénéré mais une création ininterrompue, jusque dans l’exil, 2010, www.fondationshoah.org

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.