Beginning in the late seventeenth century, Baroque art had been gradually emptying itself of both meaning and communicative effectiveness. Having exhausted the impetus of papal Rome in dictating tastes in art (although Rome had nevertheless remained during the eighteenth century an important point of reference for artists, albeit not a hegemonic one), an international style began to spread (but one that found its premises in France) based on refinement, decorativism, and pleasantness. Decorations and paintings were no longer, as in the seventeenth century, to amaze the observer, but were to provide aesthetic pleasure. This is precisely why the new style, which took the name rococo (from the French rocaille, a type of decoration made of stones and shells), was born and spread within the European courts. Precisely because of the international characteristics of rococo, a great many Italian painters found themselves engaged outside the borders of the peninsula.

The first important forerunner of Rococo taste in Italy was the Ligurian Gregorio De Ferrari (Porto Maurizio, 1647 Genoa, 1726): a pupil of Domenico Fiasella and collaborator of Domenico Piola, De Ferrari developed, in his decorative fresco works, a language that took from the Baroque the compositional layout based on quadrature, with the faux architectures often connoted by bizarre curved lines, but his scenes, although still marked by a late Baroque dynamism that sometimes blossomed into virtuosity, were no longer aimed at arousing effects of wonder. Indeed, these were compositions with serene and refined characters, which were emptied of any celebratory intent although they were present in the palaces of wealthy Genoese families: an example of this language is theAllegory of Spring that decorates one of the rooms of the Palazzo Rosso in Genoa, once the residence of the Brignole-Sale family.

A key artist for understanding the developments of the Rococo taste in Italy is Sebastiano Ricci (Belluno, 1659 - Venice, 1734), a painter of great ingenuity who had trained in a Venice that in the eighteenth century would become not only a destination for international travel but also a major artistic center, where all the trends of eighteenth-century painting would be experimented with and where certain genres, such as vedutismo, would find their greatest flowering. To his Venetian training (Ricci was especially attracted to the works of Veronese), the artist combined a stay in Rome to study the works of great Baroque decoration, from which he learned perspective illusionism. With Sebastiano Ricci, painting in Italy made a decisive turn in the Rococo direction: the Venetian painter’s compositions are distinguished by the warm, enveloping light that lends elegance to the scenes, by the liveliness that is one of the hallmarks of Rococo decoration, and by the lightness of the refined atmospheres that also highlight, very often, that sensuality suited to satisfy the tastes of patrons, and which represents another specific Rococo trait(Venus and Adonis, 1707-1710, Florence, Pitti Palace).

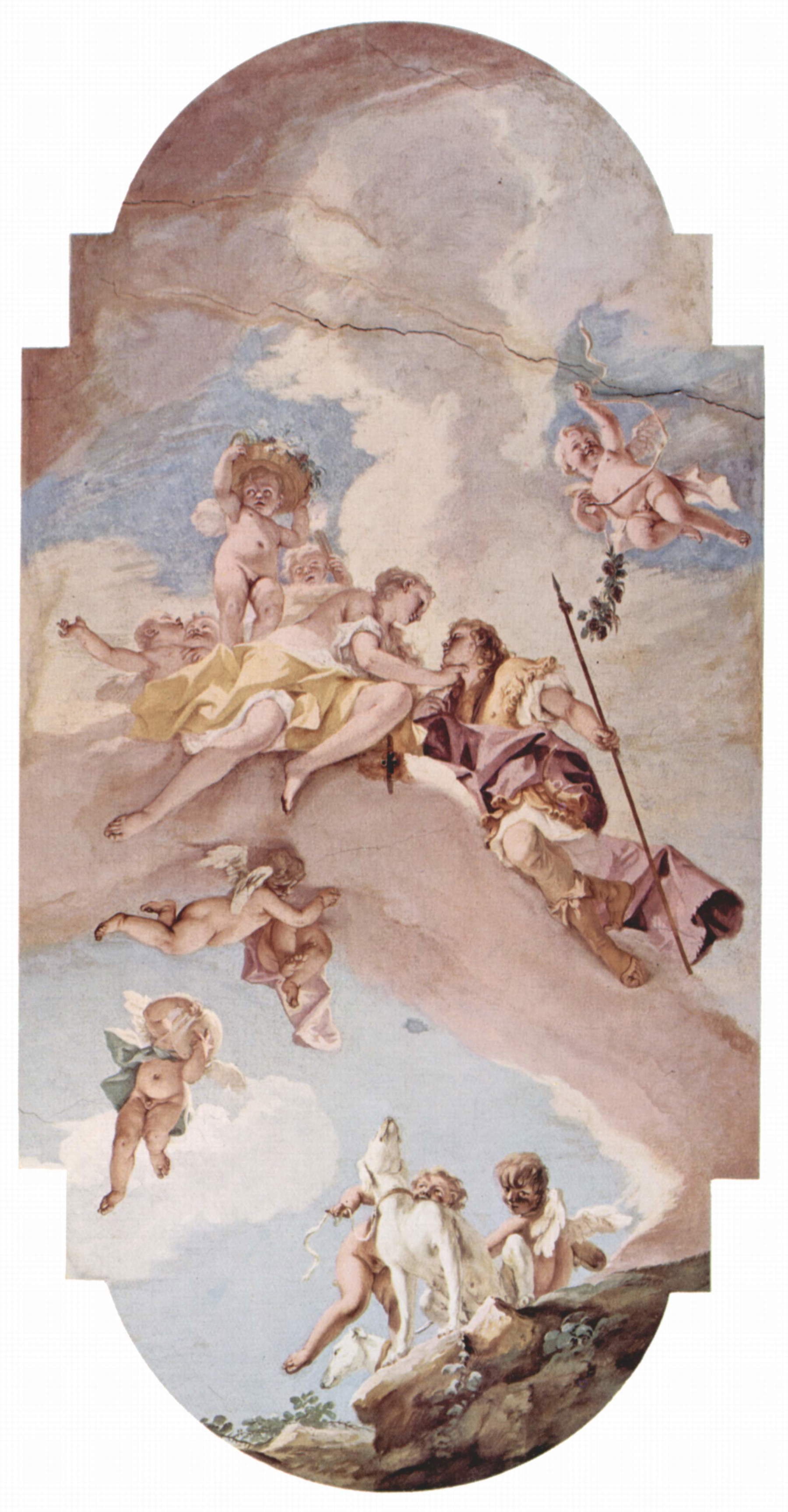

In fresco decoration, however, the greatest exponent of Rococo in Italy is Giambattista Tiepolo (Venice, 1696 - Madrid, 1770), also a native of Venice. Tiepolo was trained on naturalist and anti-classical schemes, so much so that his early production is marked by the dramatic tenebrism that was fairly widespread in early 18th century northern Italy, but the artist soon came into contact with the art of Sebastiano Ricci and made a breakthrough by following the more refined taste of the time. Thanks to extreme ductility and his ability to filter different suggestions quickly, Tiepolo developed a fast and confident technique, characterized by great and imaginative inventiveness and extraordinary compositional immediacy.

With Giambattista Tiepolo, the magniloquence of the Baroque style was now completely outmoded: terse and delicate atmospheres, orderly and balanced installations albeit with rather complex schemes (order in complexity was a typical feature of the Rococo style), all characterized by the desire to create a painting that was no longer real but consciously illusory, to the point of verging on the surreal It was after all a painting in line with the taste of the time, which did not favor a realistic narrative, but an imaginative one that nevertheless produced delight and complacency.

Another interesting exponent of Rococo in fresco decoration was Jacopo Amigoni (Venice?, 1682 - Naples, 1752), who favored Arcadian painting, that is, subjects that were mainly pastoral fables taken from classical mythology, and painted with serene, cheerful and reassuring atmospheres.

Eighteenth-century refinements found an interpreter of the highest caliber in Rosalba Carriera (Venice, 1673 - 1757), who specialized in portraiture, placing her name among those of the most sought-after artists throughout Europe (Rosalba Carriera in fact worked not only in Venice, but also in Paris and Dresden, and had among her patrons many of the most powerful rulers of the time, who often passed through Venice on visits). The artist was capable of subtle representations of subjects, made delicate by her use of pastel, which she was the first in Italy to use systematically and which, thanks to her, spread throughout Europe. Her innate ability to thoroughly penetrate the psychology of the character and render it on the painting in a masterful way, so much so that she became probably the greatest portrait painter in Europe at the time, as well as among the most influential personalities, for later portraiture owes much to her.

Another Venetian, Pietro Longhi (Venice, 1702 - 1785), was a painter of Rococo taste, although he oriented his researches in a different way: to the large fresco decoration, Longhi preferred a small-format painting, which recounted the daily life of Venice at the time. However, his paintings differed from those of the markedly realist painters in that Longhi preferred refined and intimate atmospheres. With his scenes often set in interiors, he appealed primarily to an aristocratic clientele, those of the Venetian aristocracy, who had their portraits portrayed in his works. The result is an unapologetic portrait of a Venice still caught up in its hedonism and worldly pleasures while, on the other hand, it was experiencing its period of greatest decline, which a few years after Pietro Longhi’s death would lead, in 1797, to the loss of its millennial independence. Pietro Longhi’s scenes appear realistic to us but seem almost soulless, with characters who seem almost figurants rather than real men and women.

All the contradictions of the society of the time, even more than in Pietro Longhi’s painting, are highlighted by a free, stravange and highly original painter like Alessandro Magnasco (Genoa, 1667 - 1749), an artist who cannot be pigeonholed into any current because of his out-of-the-box and completely anti-classical painting. The Genoese Alessandro Magnasco sensed that he lived in a society characterized by profound social differences, and instead of painting pictures or frescoes with reassuring scenes as most of his contemporaries did, he plunged into a reality of poverty, abuse, and torture, which the artist rendered on canvas with a very realistic flair that anticipated much of nineteenth-century art, thanks to his technique based on very rapid touches of the brush, which with just a few strokes outlined the disturbing figurines that populate his paintings.

Comparable in flair, interests and critical will to Salvator Rosa, Alessandro Magnasco sought his subjects in the slums of the society of the time: the protagonists of his paintings were thus gypsies, poor friars, beggars, street actors-prisoners depicted in scenes of interrogation or torture. And like Salvator Rosa, though to a lesser extent, Alessandro Magnascò developed a poetics of the horrid where gloomy and monstrous elements were not lacking (as in The Sacrilegious Theft). For Alessandro Magnasco, moreover, the landscape was also far removed from the idealized landscape of his contemporaries: his landscapes preferably depict an unspoiled but at the same time disturbing nature. Alessandro Magnasco’s painting was but a natural outgrowth of the contrasts of eighteenth-century society.

A realist poetics, albeit with less radical results, was carried on by Giuseppe Maria Crespi (Bologna, 1665 1747) and Giambattista Piazzetta (Venice, 1683 1754): the former was a painter who consciously moved away from the Arcadian painting of the time to give his subjects a more immediate and popular liveliness, producing compositions closer to everyday reality, with a painting where very often even low-profile subjects (Fiera paesana) find a place. Piazzetta, harking back to Giuseppe Maria Crespi himself and to Caravaggio’s naturalism of the 17th century, created works in which the characters, moving within somber atmospheres just like those of the naturalist painting of the previous century, were connoted by a strong drama that continued that desire for the viewer’s emotional involvement that had almost disappeared from Rococo poetics (Martyrdom of St. Jacopo). Piazzetta was a very singular figure on the Venetian scene, in that to the refined atmospheres of his countrymen he showed a preference for tense and pathetic scenes, which often featured subjects of popular taste.

Classicism in the eighteenth century was not abandoned, but was continued especially in Rome, a city where the main protagonist in the eighteenth century was Pompeo Batoni of Lucca (Lucca, 1708 Rome, 1787): the eighteenth-century classicism of Pompeo Batoni continued the great tradition of classicism of artists such as Annibale Carracci, Guido Reni, and Domenichino, from whom the artist was directly inspired, also taking considerable cues from Raphael and ancient art. However, Pompeo Batoni’s classicism, compared to that of the seventeenth-century painters, also contained hints of a more explicit drama, stemming from probable reflections on Baroque art(San Marino Raises the Republic). However, the pathos was tempered by the remarkable grace typical of Batoni’s poetics, anticipating the neoclassicism that would arise toward the end of the century. Pompeo Batoni was also an innovative artist in that he invented the type of portrait against the backdrop of ancient ruins, which was particularly appreciated by wealthy foreign visitors who came to the capital and wished to bring home a memento of their travel experience (Portrait of Richard Milles).

As for landscape painting, on the other hand, the greatest exponent of the genre at the beginning of the century was Giovanni Paolo Pannini (Piacenza, 1691 - Rome, 1765), who specialized in landscapes with ancient ruins but also in scenes of festivals and views of art galleries and cities (Gallery of Views of Ancient Rome), resulting in a richly scenic production, where the artist gave free rein to his imagination (so much so that what is seen in his works is often a figment of his imagination rather than an objective description) and to his own decorative taste.

|

| Eighteenth-century art in Italy: developments, styles, major artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.