“Most singular painter,” Giorgio Vasari called him, and Antonio Allegri, better known as il Corre ggio (Correggio, c. 1489 - 1534) from the town where he was born in 1489, is one of the most singular painters in the history of art. The artist began his career observing the results of the painting of Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo, 1431 - Mantua, 1506), from whom he derived the harsh sign (which would later become soft and delicate thanks to his encounter with Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael) as well as the perspective illusionism, and he was able to rework the different sources from which he drew suggestions to derive a very original and innovative style, which made Correggio one of the geniuses of painting, not only of the 16th century. With his spectacular frescoes (read an in-depth look at the naturalness of Correggio’s works here) he was a source of inspiration for Baroque artists, his religious-themed paintings are among the most intimate and elegant ever, and his mythological-themed ones made him a master of eroticism, with subjects always approached with great refinement.

His training began in the workshop of his uncle Lorenzo Allegri, a modest local painter from whom he probably learned his first rudiments. Some biographies want him to be a pupil of a certain Antonio Bartolotti, another Correggio artist who was also modest, however, the real artist who had a fundamental impact on him was Andrea Mantegna.Antonio Allegri was in Mantua starting, roughly, in 1503, although we have no certainty about the dates. Here he got to know the great Venetian painter and was probably also one of his pupils. What is certain is that in Mantua Correggio had contact with Mantegna’s son Francesco, which enabled him to conduct in-depth studies of the great artist’s works, which unmistakably marked the early stages of Antonio Allegri’s career. It is then safe to assume that Correggio came into contact with the art of Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) precisely in Mantua: the great Tuscan artist, in fact, stayed in Mantua, at the court of the Gonzaga family, at the end of the 15th century, and Leonardo’s art was fundamental for Antonio Allegri, who in the wake of the results of Leonardo’s art had the opportunity to radically revisit his way of painting, approaching, starting in the 1510s, Leonardo’s sfumato and becoming one of its great interpreters.

Correggio was a highly innovative artist: he proposed new solutions, was able to blend motifs derived from different sources to give life to an original style that was taken as a model by many artists, first and foremost Parmigianino who came from the same lands as Correggio and for whom Antonio Allegri was an indispensable figure. Several artists looked to Correggio and drew from it useful elements for their own art: among the greatest it is enough to mention Federico Barocci, Guido Reni, Luca Cambiaso, Federico Zuccari, Giovanni Lanfranco, Carlo Maratta, Cigoli, and Carlo Cignani. Decades and centuries later, therefore, Correggio’s works continued to be studied, copied, modeled, and admired.

|

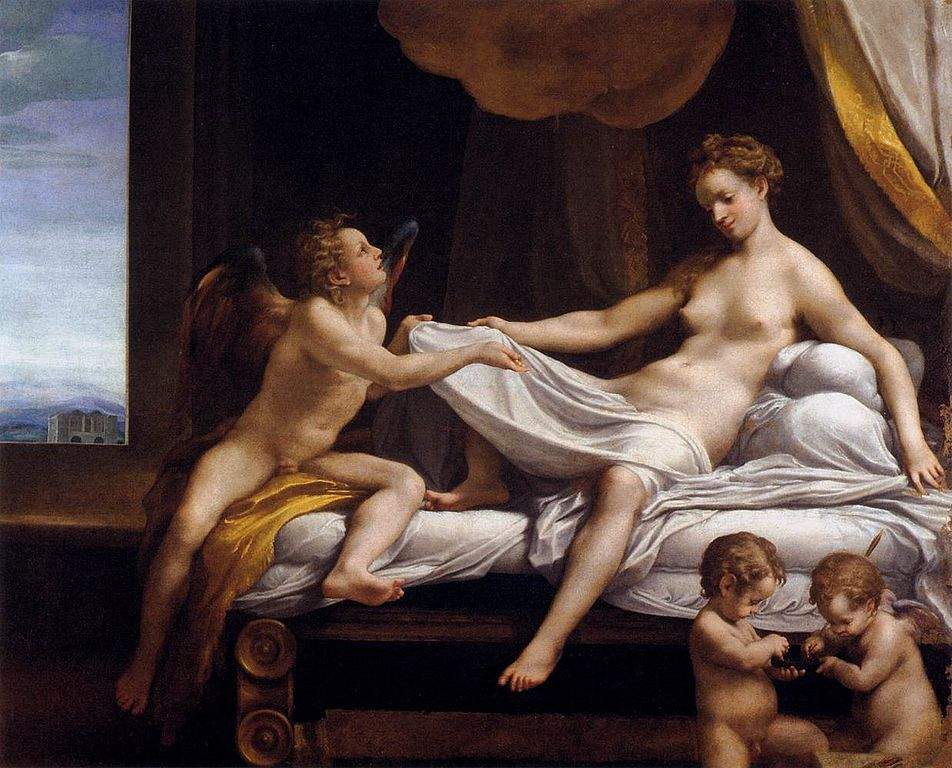

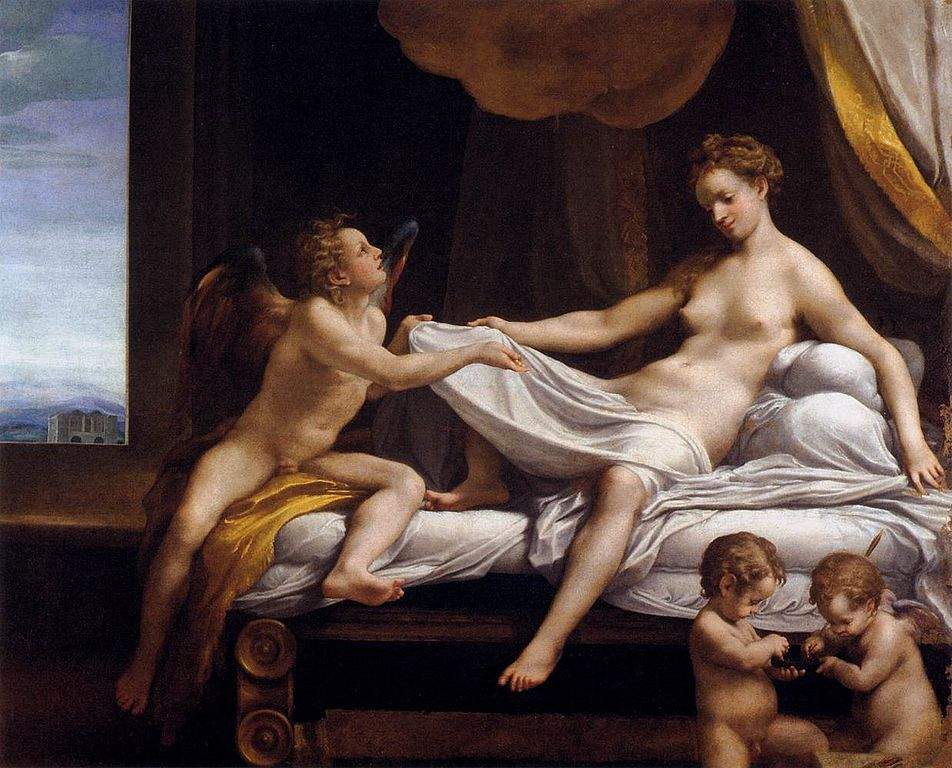

| Correggio, Danae (c. 1531-1532; oil on canvas, 161 x 193 cm; Rome, Galleria Borghese) |

Antonio Allegri was born about 1489 in Correggio to Pellegrino, a merchant, and Bernardina Piazzoli. Probably around 1500 he began to learn the first rudiments of painting from his uncle Lorenzo, a painter of modest importance. Later he is in Modena, perhaps in 1503, and here he studies with the painter Francesco Bianchi Ferrari. Around 1504 he went to Mantua (the exact year is not known, however) where he learned the painting of Andrea Mantegna. It is traditionally dated to 1507 this year that Antonio made his debut in Mantegna’s funeral chapel: the great Venetian painter had died the previous year. In 1511 the artist was certainly in Mantua where he had contact with Francesco Mantegna, son of Andrea. He began to paint the fresco of the refectory of the Polirone monastery in San Benedetto Po, not far from Mantua, around 1513(read more about the Polirone monastery here). In his hometown, in 1514, he was commissioned to paint the Madonna of St. Francis.

Around 1515 he perhaps made a trip to Rome, where he had the opportunity to see the works of Raphael Sanzio and Michelangelo Buonarroti. In 1518 he was called to Parma by Giovanna da Piacenza, abbess of the monastery of San Paolo: the artist was commissioned to decorate the Camera della Badessa. In 1520 he married Girolama Merlini de’ Braghetis, and in the same year he was commissioned to paint the fresco decoration of the dome of San Giovanni Evangelista in Parma(read more here), which would be finished in 1523. In 1521 his first son, Pomponio, was born, and he was to become a painter. In 1522 the artist began painting theAdoration of the Shepherds also known as La Notte(read more about Correggio’s Nights here). Following his fame for the dome of St. John the Evangelist, he obtained the prestigious commission to decorate in fresco the dome of Parma Cathedral: the theme is theAssumption of the Virgin and the work would be completed in 1530.

In 1524 his daughter Francesca Letizia was born, and in the same year Antonio moved to Parma. His third child, Caterina Lucrezia, was born in 1526, while the following year Girolama gave birth to Anna Geria, his fourth daughter. In 1527 Antonio Allegri began painting The Education of Cupid and Venus and Cupid Spied on by a Satyr, his first movable works with mythological subjects. In 1528 he painted the Madonna and Child with Saints better known as Il Giorno. and in 1530, commissioned by Isabella d’Este, he executed two paintings, theAllegory of Virtue and theAllegory of Vice. In the same year Duke Federico II Gonzaga commissioned him to paint the cycle of the Loves of Jupiter. The artist died suddenly in Correggio on March 5, 1534.

|

| Correggio, Vault of the Camera di San Paolo (1518-1519; frescoes; Parma, Camera di San Paolo) |

|

| Correggio, Assumption of the Virgin (1522-1530; frescoes; Parma, Duomo) |

|

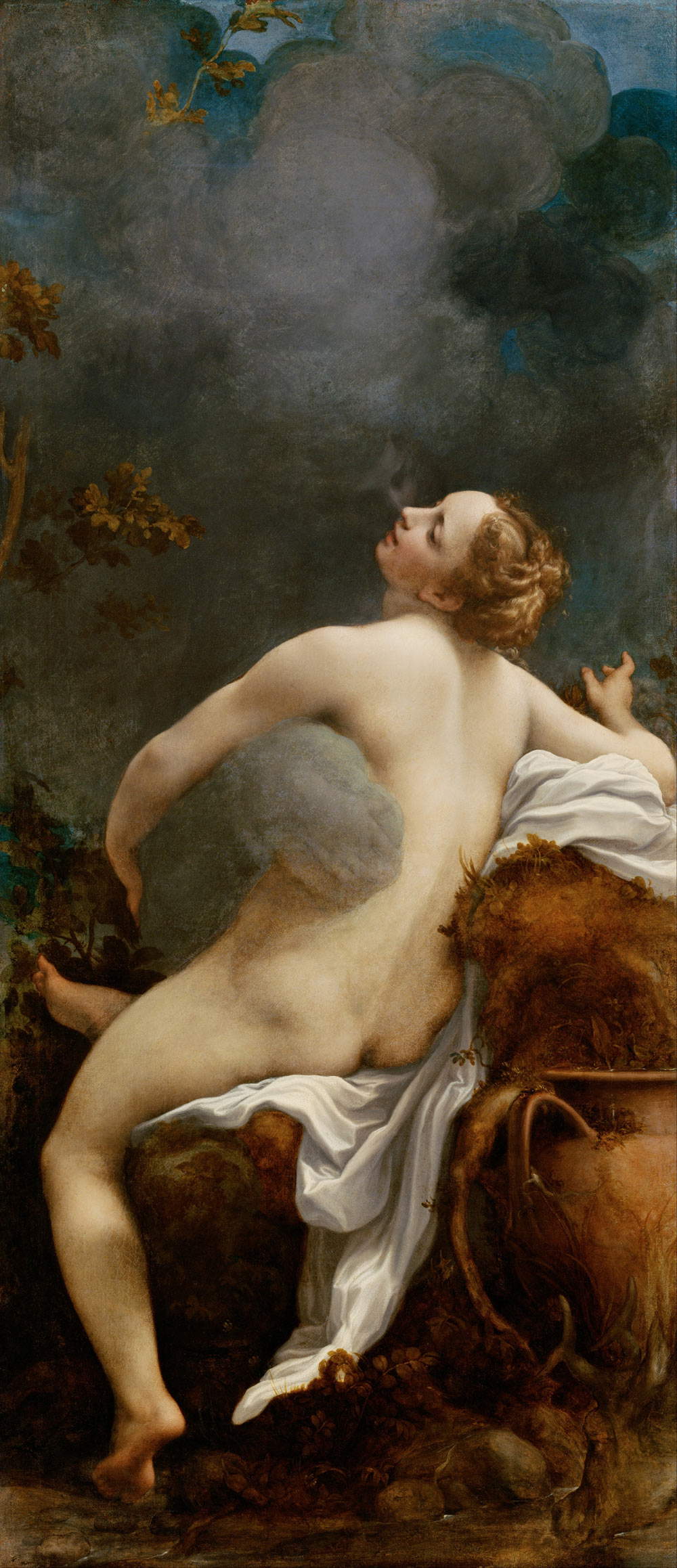

| Correggio, Jupiter and Io (1531-1532; oil on canvas, 163 x 74 cm; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) |

Correggio’s earliest works include two tondi preserved in the Museo Diocesano in Mantua, from the Basilica of Sant’Andrea: they are a Deposition and a Holy Family with St. John and St. Elizabeth; they are detached frescoes that were located in the basilica itself, and despite the condition in which they have come down to us it is possible to read in them the Mantegna manner typical of the early part of Correggio’s career. It is then possible to mention a further detached fresco, a Madonna and Child with Saints Francis and Quirino, which is in the Galleria Estense in Modena, and it is a work that has an inscription bearing the date 1511, although it is not known when exactly the painting was made. We also do not know for whom it was made, but given the presence of Saint Quirino, who is the patron saint of the city of Correggio, it is obvious to think that it was made in the city of his birth, perhaps specifically for the church dedicated to the saint (who, moreover, holds up a model of the city of Correggio in the painting to offer to obtain protection over the city from the Madonna beside him). It is a painting with colors and features that still recall Mantegna, just as the features of the characters also recall Mantegna. The approach to Leonardo da Vinci began to manifest itself from the 1910s, and the first work from which it can be inferred is a Nativity with St. Elizabeth and St. John in adoration of the Infant Jesus, a work from about 1512 that is in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan. The scheme is still linked to Mantegna stylistic features, but now the artist also tries to graft onto this Mantegna framework Leonardo’s aerial perspective, to be found especially in the landscape in the background, with a gloomy atmosphere and hills that recall Leonardo’s solutions. Another artist Correggio looked to, especially for the depiction of characters, is Lorenzo Costa (Ferrara, 1460 - Mantua, 1535). Also in Milan, but at the Castello Sforzesco, there is a work that can be dated to a period between 1514 and 1517, and it is one of the most Leonardesque of this phase: it is a Madonna and Child with St. John (also known as Madonna Bolognini), which takes up the pyramidal structures typical of Leonardo in this kind of work; moreover, the aerial perspective that Correggio makes use of in the work is entirely borrowed from the art of Leonardo da Vinci. Now in Correggio’s work, sfumato also appears, and it is especially noticeable in the face of the Madonna, while the painter’s typical delicacy still remains as one observes the expressions of the two children, Jesus and St. John.

Correggio, as anticipated, was a great innovator in large fresco decorations. The examination can begin with the decoration of the Camera della Badessa, executed between 1518 and 1519 in the Convent of San Paolo in Parma, so much so that it is also known as the “Camera di San Paolo” (the decoration was commissioned by the abbess of the convent, Giovanna da Piacenza, and it was a room used for various functions, including reception and administrative functions as well as a meeting place for humanists and men of letters who frequented the monastery). Correggio creates a spectacular illusionistic decoration, with cues drawn from the Mantegna lesson: the artist creates a mock arbor divided into sixteen segments bordered by reeds, and within each of the segments is an oval over which cupids face, with the sky in the background, while at the base of each segment are lunettes made in monochrome that house mythological figures. It is a room reminiscent, on the one hand, of the illusionism of Mantegna’s Bridal Chamber(read more about the work here) and, on the other hand, also of Leonardo da Vinci’s Sala delle Asse in the Castello Sforzesco(read more about it here), due to the fact that the vault houses plant motifs simulating an open-air environment, with an interesting dialogue between man and nature. We do not know exactly what the themes of the fresco were, but it is possible to imagine that they were inspired by the abbess Giovanna, a woman of culture: Roberto Longhi, for example, has proposed interpreting the work as an allegory of hunting, a theme to which the presence of the goddess Diana on the fireplace would also refer, while according to Erwin Panofsky the iconographic program would refer to the moral virtues of the abbess. The Camera represents an important turning point in the style of Correggio, who proves himself here to be a fully mature artist capable of very original and innovative solutions, because no one had ever before produced a decoration that imitated an outdoor environment and at the same time told a cultured and refined story, designed to be understood only by a close circle of people (as was usual at the time): these frescoes would later be a model for Parmigianino’s Stories of Diana and Actaeon.

In contrast to the Camera della Badessa, which is poorly documented, the fresco decoration of the dome of St. John the Evangelist is well documented: it was made between 1520 and 1524, and the theme with which Correggio decorates it is the vision of St. John the Evangelist at Patmos. St. John is placed perpendicular to Christ, and Correggio’s innovation consists in the realization of the decoration of a dome that lends itself to different points of view without having a privileged one: the faithful, from their point of view, observe before them the figure of Christ in all his majesty while, on the other hand, the officiants had before them the figure of St. John (St. John was to be an example for the religious). Correggio here employs a strong understatement to create a powerful and spectacular illusionistic effect, succeeding in creating one of the most original masterpieces of the entire 16th century. Here the suggestions are to be found again in Mantegna for the illusionism and in Raphael for the figures of Christ and the Apostles.

The dome of San Giovanni was perhaps the work that gave the most fame to Correggio, who, again in Parma, was commissioned in 1522 to decorate the dome of the cathedral, a prestigious task that the artist carried out between about 1526 and 1530. The theme is theAssumption of the Virgin: the painter developed it in a highly original way that was a precursor to Baroque art, since all the figures of saints, blessed and characters from the Bible are arranged on the clouds following a spiral movement toward the center, where we see the dazzling golden light of Christ coming over to meet the Madonna. The Correggio revolution occurs in the complete elimination of architecture, as in San Giovanni (similar decorations in Correggio’s time were always placed within rigorous architecture). The difficulty in understanding the work in terms of both its innovative stylistic aspects and, on the other hand, its legibility, drew a great deal of criticism on Correggio: at the time, his work was not particularly beloved. It was in fact a very modern work and really ahead of its time. Famous is the anecdote of the defense of Titian, to whom tradition attributes the famous thought that if the Parmesans had overturned the dome and filled it with gold, they would never have paid it enough. The critical fortune of this work then followed alternating phases over the centuries: today, the value of this work is clear, recognized and undisputed. Obviously, it is not possible to consider Correggio a Baroque artist, because this work was not created with the intent to amaze the viewer; moreover, Correggio lacks the imposing scenic apparatus that would be characteristic of Baroque painters. However, the Emilian painter deserves credit for having had, through his imagination and ingenuity, several insights that anticipated Baroque art.

Finally, a lunge into theerotic art in which Correggio excelled is possible. It is possible in this sense to cite the cycle of the Loves of Jupiter: four of the most intense works of Antonio Allegri’s entire output, painted on behalf of Duke Federico II Gonzaga, who commissioned them from him in 1530, but they were completed from 1531 and in the following years. The works are Leda and the Swan (Staatliche Museen, Berlin), Danae (Galleria Borghese), Jupiter and Io, and the Rape of Ganymede (the latter both in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). Taking Jupiter and Io, a work from about 1531-32, as an example, we are confronted with a very engaging, refined and sensual work: Io, the nymph beloved by Jupiter, is depicted from behind, following a scheme that was innovative for the time but taken from ancient works (e.g., the Ara Grimani preserved in Venice, which depicts the union between Cupid and Psyche). The nymph is completely naked, and Jupiter, who takes the form of a cloud, is embracing her to unite with her: Io has her head recumbent and her eyes closed, in a very natural way (naturalism is another of the main characteristics of Jupiter’s love cycle) and is abandoning herself to Jupiter. It should be noted that the intercourse is not depicted in great detail: Correggio prefers to leave the viewer’s imagination free, thus offering further evidence of the refinement of his composition. Despite the theme (Jupiter’s loves were often viewed with negative connotations), the story is told with poetic vein, offering the viewer one of the most moving love scenes in all of art history.

|

| Correggio, Deposition (c. 1509-1511; detached fresco, 150 x 150 cm; Mantua, Museo Diocesano) |

|

| Correggio, Madonna and Child between Saints Quirino and Francis (c. 1505; detached fresco, 94.5 x 111.5 cm; Modena, Galleria Estense) |

|

| The frescoes in the dome of San Giovanni in Parma |

Wanting to begin your knowledge of Correggio, you can start in his hometown, where the Museo Civico “Il Correggio” preserves a youthful Pietà, a Face of Christ and a drawing and offers interesting insights into his entire career. It is impossible not to visit Parma, and in particular the National Gallery at the Complesso della Pilotta (where theCoronation of the Virgin, Madonna of the Staircase,Annunciation, Day and Madonna of the Bowl are located), the Camera della Badessa, the Duomo and the church of San Giovanni. Between Mantua and Modena, however, it is possible to see some early works: the frescoes in Andrea Mantegna’s funeral chapel (in Mantua, Basilica di Sant’Andrea), the tondi in the Museo Diocesano in Mantua, and the Madonna and Child between Saints Quirino and Francesco at the Galleria Estense in Modena, where the slightly later Madonna Campori is also kept. In Milan, the Pinacoteca di Brera houses the Nativity with Saints Elizabeth and John and theAdoration of the Magi, while the Madonna Bolognini and Portrait of a Man with Book are on view at the Castello Sforzesco. Works by Correggio are also at the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples (the Zingarella, the Saint Anthony Abbot), the Uffizi (the Rest during the Flight into Egypt) and the Galleria Borghese in Rome (the Danae).

As for foreign museums, Correggio’s works are kept at the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden (the Madonna of St. Francis, the Madonna of St. Sebastian, Night), the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (a youthful Madonna and Child, the Rape of Ganymede, Jupiter and Io), the National Gallery in London (the Farewell of Christ to His Mother, the Madonna of the Basket, theEducation of Cupid), theHermitage (where there is a very famous Portrait of a Lady: read more here), the Louvre ( Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria in the Presence of St. Sebastian, Venus and Cupid Spied by a Satyr), the Staatliche Museen in Berlin(Leda and the Swan).

|

| Correggio, life and works of the Emilian Renaissance painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.