Land Art (literally “earth art”) is an artistic language that arose in the United States of America in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The matrix of this experience, like that of Arte Povera and other movements orbiting in the context of the Neo-avant-gardes, was subject to a variety of suggestions and influences, so it is difficult to precisely define its boundaries.

In general, Land Art is recognized in works with impactful dimensions, executed outdoors, in the open air of natural settings. It is characterized by abandoning traditional art materials and turning in favor of direct and momentary intervention in the natural landscape. Given the confrontation with the landscape environment, very rarely can some of these works be mounted inside galleries and museums, being essentially executed with materials available in nature. More often, their size makes transportation and composition in indoor spaces impossible, so the only documentation that remains of such works is photography, video or representation of plans, projects.

Land Art is in fact the title of a documentary filmed in 1969 by German gallerist Gerry Schum about the interventions made in direct contact with nature by a number of land artists: Marinus Boezem, Walter De Maria, Barry Flanagan, Michael Heizer, Richard Long, Dennis Oppenheim and Robert Smithson. The interventions of these artists step out of the traditional context, the museum or gallery space, and into immense and unspoiled territories, including deserts, prairies and frozen lakes. In this way, these creative personalities demonstrated that natural phenomena themselves can constitute true works of art.

Land Art was born in the United States of America, within an essentially anti-formal attitude, antithetical to the figurativism presented by the contemporary experiences of Pop Art. Land Art is a new and extra-pictorial artistic language, an experimental pursuit that falls within the intellectual dynamic of the Neoavantgardes, those trends such as New Dada, Body Art, Fluxus, Conceptual Art and Arte Povera that developed between the early 1960s and the early 1970s. These movements actively addressed the problem of art’s relationship with society in its broadest sense.

Land Art fell squarely among these artistic experiences. Specifically, this art form had a very close relationship with the environment and nature.

In 1968, land artist Robert Smithson curated theEarth Works exhibition in which more or less the same artists from Gerry Schum’s documentary filmed the following year had participated, exhibiting photographic, graphic and filmic documentation of some of their interventions made outdoors. Because of the obvious and intrinsic connections with the natural environment, land art was also called Environmental Art. Land art works are not sculptural installations in natural settings: the artist does not introduce extraneous elements into the landscape, but shapes the land in his or her own way, making nature an accomplice. He modifies its appearance, using only materials that the ecosystem makes available.

Elements and materials of Land Art are stones, vegetation, timber, water, sand, snow, wind, lightning and earth. In doing so, the environmental artist engages in a dialogue with the environment, conducted with an awareness: over time, this form will inexorably change. The signs artificially imprinted in the land will once again be the object of reappropriation by nature, which will transform and modify them with the changes vital to the ecosystem. So the character of these works is essentially ephemeral.

Because of this fading character, the land artwork is essentially a mediated artwork. One mode of fruition of the performative art fact in this case is that of documentation through video or photography, fundamental tools for public enjoyment and for allowing the autonomy of these works, disengaged from the material contexts and predefined boundaries of museums and galleries. The transience of the composition and materials used, in this way, no longer poses a problem to the transmission of the concept that animates the work. Land art research was then distinguished by the component of the rejection of the work of art as object-manufacture. The land work eschews the laws of the commercial network of the art market. The consideration of nature is that of equal co-author in the moment of artistic creation. Underlying all these criteria remains the desire to work in direct contact with pristine environmental settings, conceived not as something to be abused, but something to be confronted with, to operate an exchange. Landscapes were thus conceived as immense supports, new canvases on which to intervene using only the materials already customarily found there.

Land Art developed spectacularly especially in the United States, which in many states offers extremely wild and evocative landscapes. Artists here have at their disposal uncultivated, unspoiled and endless spaces among canyons, deserts, great lakes.

Richard Long (Bristol, 1945), is undoubtedly a forerunner of this artistic attitude, although he does not like to be called a land artist. He worked outdoors, with operations on the landscape, and also indoors, with works made of stones or branches, with plans and photographs. Long reproduced in enclosed gallery or museum spaces the simple ephemeral sculptures, primal accumulations of stones, made during his explorations. These were primary geometric forms: the Stone Circle series, which consisted of spirals, straight lines executed with locally found materials. Although the working criterion may appear ecological, it was nonetheless a matter of transferring a geometric and organized form from the human mind into the chaos pertinent to the natural order. With his stone circles, Long certainly alluded to magic circles, with that ritualistic significance of prehistoric sculpture. However, this “archaeological” dimension is far removed from American Land Art, which instead seems to send the geometrisms of Minimal Art outward with unprocessed materials.

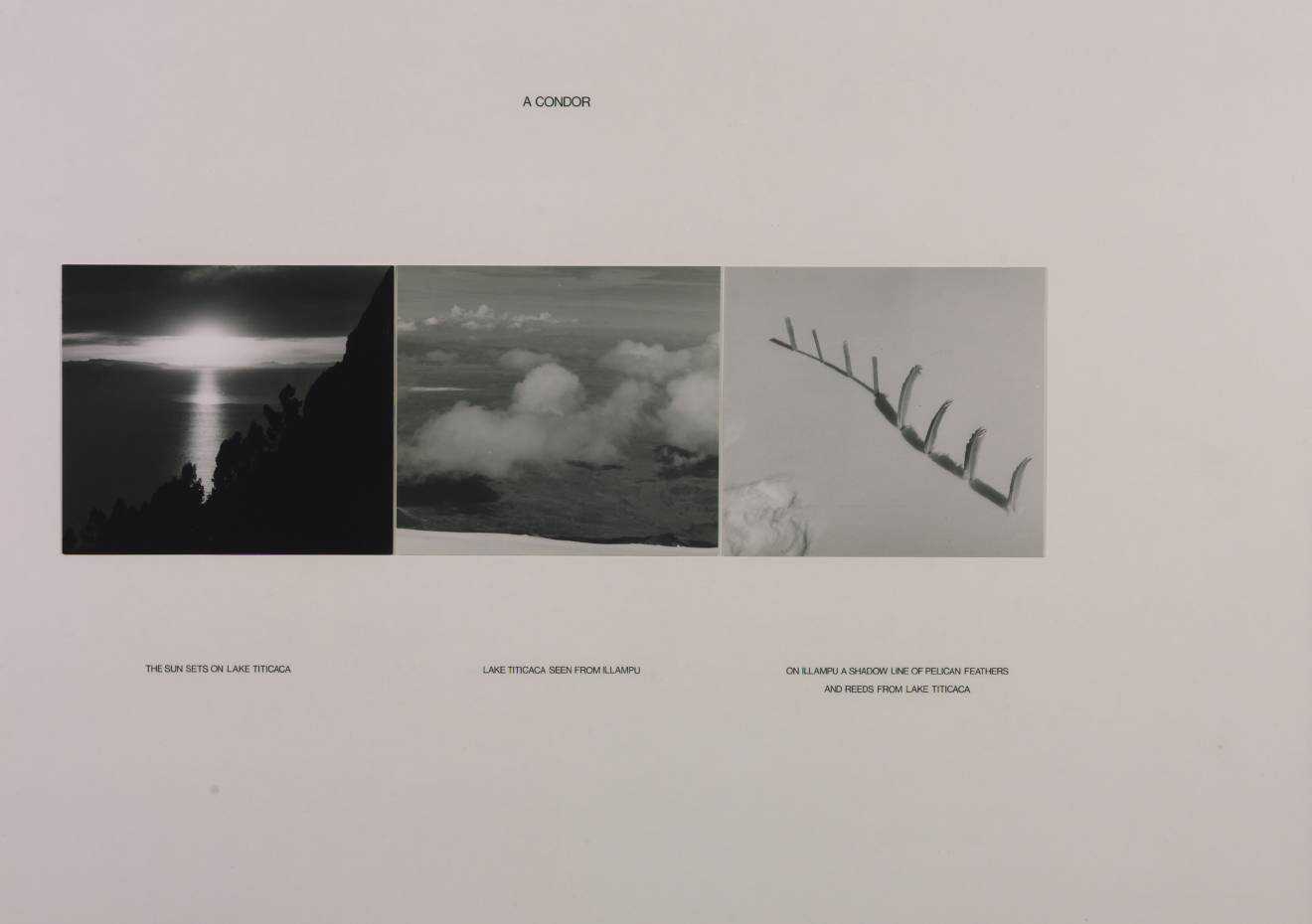

Richard Long’s interventions are thus less radical, along with those of Hamish Fulton (London, 1946). These were temporary displacements in the territory, documented by maps, photographs, collections of objects. In the Walking Journeys, long journeys on foot in even impervious areas taken by the two artists, the relationship with the landscape becomes an autobiographical projection of an accomplished journey.

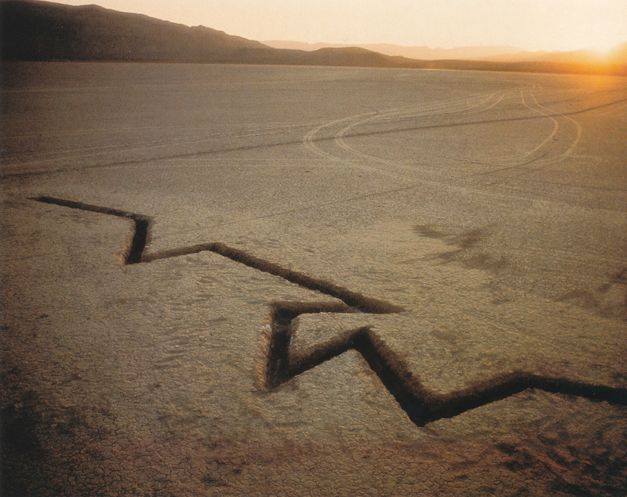

Also influenced by Richard Long was the Dutchman Jan Dibbets (Weert, 1941). He drew a long green strip in a meadow by simply tearing out the white flowers that dotted it along a preordained path. He created illusory images by cutting irregular rectangular parts of offense and thus obtained anamorphic forms that were based on anoperation performed in negative. The negative is also in the sculpture of Michael Heizer (Berkeley, 1944), an American artist, who created exterior monuments by digging out the earth and cementing cavities. These were huge works, often conducted in barren and deserted locations, such as the famous double negative that pierces the steep walls of a plateau with a regular cut through a kind of jagged gorge visible from above. Even in the work of an artist like Dennis Oppenheim (Electric City, 1938 - Manhattan, 2011), the idea of the negative recurred often. Large plowed surfaces and furrows in the snow executed in a certain pattern became large geometric designs, when viewed from the sky, like concentric circles. Meanwhile, they also represented a real-life counterpart of a path drawn on a map: theidea (the path) became concrete (the furrow, the track).

Such large enterprises, given their cost and unmarketability, required large sponsorships. Moreover, they are works that are almost impractical to the general public: suffice it to say that often the best view of these works is from ahelicopter. Robert Smithson (Passaic, 1938 - Amarillo, 1973), was one of the legendary performers of this art form and died during an airplane reconnaissance in search of suitable terrain for one of his works. His best-known work is Spiral Jetty, created in 1970 in Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Thanks to the efforts of many workers at work with bulldozers and bulldozers, tons of boulders and earth were raised and placed back to form a huge spiral of rocks and earthy material. The spiral expands from the line to the center of the lake, drawing a primordial sign that is linked to the thousand-year history of an area. In fact, a local belief has it that huge eddies were created caused by a large underground channel, which would have connected the lake directly with the ocean.

In the moment immediately following the construction of the spiral, the circular path was passable, directly integrating the viewer, who could actively follow it, recreating its shape with his own movement. Having reached the center of the lake, the viewer had an additional perspective view of the landscape, thus a new experience of enjoying the natural surroundings.

Christo (Christo Vladimirov Javašev (Christo Vladimirov Javašev; Gabrovo, 1935 - New York, 2020) and Jeanne Claude (Jeanne Claude Denat de Guillebon; Casablanca, 1935 - New York, 2009), were among the major creators of this type of large-scale work. Christo, while more properly an artist of Nouveau Réalisme, is a creator who can be likened to the artists of Land Art: his interest centered on subverting the habits that make individuals’ relationship with the world around them opaque. At first, he used to cover everyday objects, removing them from the circuit of consumption. The object was recognized by the shapes of the package, but at the same time it became unusable.

From his meeting with his wife, with whom he moved to New York in 1964, a fertile collaboration was born and, little by little, the "wrappings" became larger and larger, coming to involve large monuments, which are covered with immense sheets. The monuments in question are buildings that are no longer paid attention to, part of a visual scenery that is now taken for granted. An example was Wrapped Reichstag in Berlin, 1971-1995 and also Wrapped Roman Wall, 1974 (Aurelian Wall in Rome). Then, the two artists intervened to cover the buildings, and by hiding them they enhanced them, making the general public feel the need for them by momentarily barring them from view. This activity began at the time of Nouveau Réalisme and during the Fluxus events. Christo had to establish real companies to complete ventures such as Valley Curtain, made in Colorado between 1970 and 1972: sponsorships aside, the only economic returns from these works were the sale of documentation, projects, films and documentaries.

More direct interventions are the installations of Walter De Maria (Albany, 1935 - Los Angeles, 2013)) that also caused spectacular natural effects. With Lightning Field, between 1971 and 1977, four hundred stainless steel rods were installed over a mile into the Albuquerque Desert in New Mexico. The intervention recalls thevertical order of lightning drawn to the ground by opposing it to the horizontal disorder generated by the uncultivated growth of plants on the ground. At the same time, it offers an extraordinary natural spectacle, both in clear skies, as the poles sparkle, and especially even in thunderstorms, when the site becomes a huge magnetic field and attracts cascades of lightning, generating light. In order to witness this spectacle, the medium this time is the guardhouses, placed at a safe distance.

James Turrell (Pasadena, 1943) also played with the sky, creating skyspaces. The most ambitious of these “pieces” was Roden Crater Project, to which the artist dedicated himself in 1977: he operated excavations inside the extinct Arizona volcano, transforming it into a place for observing the sky and constellations. Visitors can visit hypogeal chambers with openings properly oriented toward the celestial vault. In these environments, the sensory organs undergo a very strong dilation, making them extremely sensitive to every ray of light and every surrounding sound. Ahyper sensory experience of nature, with a strong psychological impact and meditative character that induces the viewer to an inner journey.

Among Italians, those who went through the land art experience was Alberto Burri (Città di Castello, 1915 - Nice, 1995). Burri’s famous Cretto stretches across the site of the old town of Gibellina, in the province of Trapani, which was devastated by the 1968 Belice earthquake. The artist created this work between 1984 and 1989, later completed in 2015. Burri planned to cement and retrace the streets and tunnels of the old town, making it a memorial: the concrete blocks were made by reusing rubble.

Seen from above, the Cretto is very extensive and appears as a series of cracks in the concrete.

|

| Land Art: birth, developments, main artists |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.