There are exhibitions that risk penalizing an artist and exhibitions that risk penalizing an audience. Rarer, and more instructive, are those that manage to take both risks with such a coherent design that the error is transformed into an exhibition system. The retrospective that the Museo della Permanente in Milan is dedicating to Jack Vettriano until January 25 belongs to this precise category and deserves to be observed carefully, because it reveals with extreme clarity how an exhibition can work badly without ever seeming improvised, and how the apparatus can take the place of the work with an almost embarrassing naturalness.

The structural fact, evident to anyone who walks through the halls with a modicum of attention, concerns the way it organizes and hierarchizes what it claims to exhibit. The official communication states that it “offers more than 80 works, including eight oils on canvas, a series of one-off works on museum paper, a cycle of photographs taken in the artist’s studio and a video in which Vettriano talks about himself and his stylistic evolution.” Everything is correct, everything is stated and perfectly transparent. And it is precisely this transparency that makes the device interesting because, in the practice of staging, the balance between these elements is anything but neutral. The eight oil paintings, although explicitly stated as the pictorial core, are never put in a position to hold a central role, but are incorporated into a uniform flow where everything applies equally. Painting is, thus, leveled and absorbed into a system that flattens out all material differences, and the result is an environment in which oil on canvas, printmaking, photography, and word coexist on the same communicative plane. Everything contributes to a single narrative effect, continuous and indistinct. Painting loses weight, density and is treated as one voice among others, as an image among images, deprived of the resistance that should constitute its primary value.

The disproportion thus does not concern the correctness of the information, but its effect in the overall functioning of the path. The enumeration of the “more than 80 works” produces the idea of a compact richness, while the experience returns a very precise distribution of weights: on the one hand a few paintings that would demand time, on the other a narrative apparatus that occupies the space and continuously directs the gaze.

At this point it is worth clearing the field of a misunderstanding that could arise here. The problem is not the presence of a few paintings: Milan knows well, and practices successfully, exhibitions built around a single masterpiece. Every year, for example, at Christmas time, Palazzo Marino hosts in Sala Alessi a monographic exhibition focused on a single work, at the initiative of the City of Milan. In that context, the choice of concentration stems from a precise confidence: confidence in the strength of the object, in its ability to sustain silence, to hold the frontal gaze, to inhabit space without any escort. The setting retracts, the word is measured and time dilates. Here the audience is treated as an interlocutor capable of staying, whereas in the Vettrian case the opposite happens. The apparatus grows in direct proportion to the fragility of the experience it seeks to support: where the painting is in danger of quickly running out, the text intervenes; where the image struggles to hold the gaze, the narrative expands.

The point, then, is about the evidence of the operation and the measure of ambition. At Palazzo Marino, the concentration stems from an explicit trust. The kind of confidence that takes shape only when the work possesses sufficient density to withstand the isolation and even the friction of protracted attention. At the Museo della Permanente, saturation responds to a different need, in which the setting becomes loquacious because Vettriano’s painting, weak in construction and poor in visual resistance, requires a context to support it. The void is filled, the silence attenuated, and the loneliness, unfortunately, shielded. The work remains at the center only in appearance, while around it a system of footholds, comments, translations and reinforcements is organized to constantly accompany its reception.

In one case the set-up retracts because the work stands on its own. In the other it expands, without much grace, because it demands continuous protection. The point is that a path that fills in this way arises from an obvious caution: that of preventing the gaze, left free, from encountering the exhibition’s limit too soon. Caution, this one, that also seems to be shared on the editorial level. The catalog, rather than opening up an autonomous critical space, almost slavishly replicates the texts in the room and entrusts reflection on the artist to a brief concluding biography, as if the exhibition itself had already said everything that needed to be said. What emerges is the impression of an operation that proceeds cautiously, without exposing itself fully, as if not even those who constructed it had really bet on the possibility that painting alone could bear the weight of attention. And when an apparatus speaks so much, it also often tells what it would rather keep silent.

Now, however, it becomes necessary to dwell on what the exhibition calls “works on museum paper,” an elegant and ambiguous formula that serves a precise function. This expression indicates fine-art prints made on archival paper, signed and certified, presented as one-off or extremely limited-run pieces. These are images derived from existing paintings, translated through high-definition printing techniques and intended for the collector market of art graphics. The result is refined, impeccable, perfectly expendable. In the context of a retrospective, this distinction takes on specific weight. Obviously, the works on museum paper make it possible to display many of Vettriano’s most celebrated subjects, often known through their media and commercial circulation, but they do so through a form that belongs to a different regime than oil painting. The printed surface privileges the recognizability of the image, its immediacy, its ability to be grasped in a single glance. In this context, pictorial matter, with its layering, corrections and resistances, slips to the margins, replaced by smooth, uniform surfaces, flawless as finished products. The economic fact, with an entrance fee set at 16 euros, makes the picture even more instructive. The visit takes on a singular physiognomy: what requires presence, distance, time, occupies a reduced space; what can live perfectly elsewhere, as on a home screen and in high definition, dominates the path.

Prints, flawless and glossy, function as visual equivalents, ready to use, more prone to substitution than deepening. Painting becomes an abandoned parenthesis within an already familiar, ordered, narratively compact iconographic archive. The visitor enters with the promise of an encounter and instead passes through a sequence of recognizable, already metabolized images, accompanied by texts and quotations that fix their meaning with administrative thoughtfulness. The layout works very efficiently in this direction. Each element concurs to stabilize the image, to make it available, manageable, frictionless. Differences in status between oil, print, photograph smooth out to the point of irrelevance. The retrospective thus presents itself as a device that privileges the circulation of the image over the presence of the work, offering a coherent, smooth, perfectly transferable vision. Inside the museum and, with identical effectiveness, outside as well.

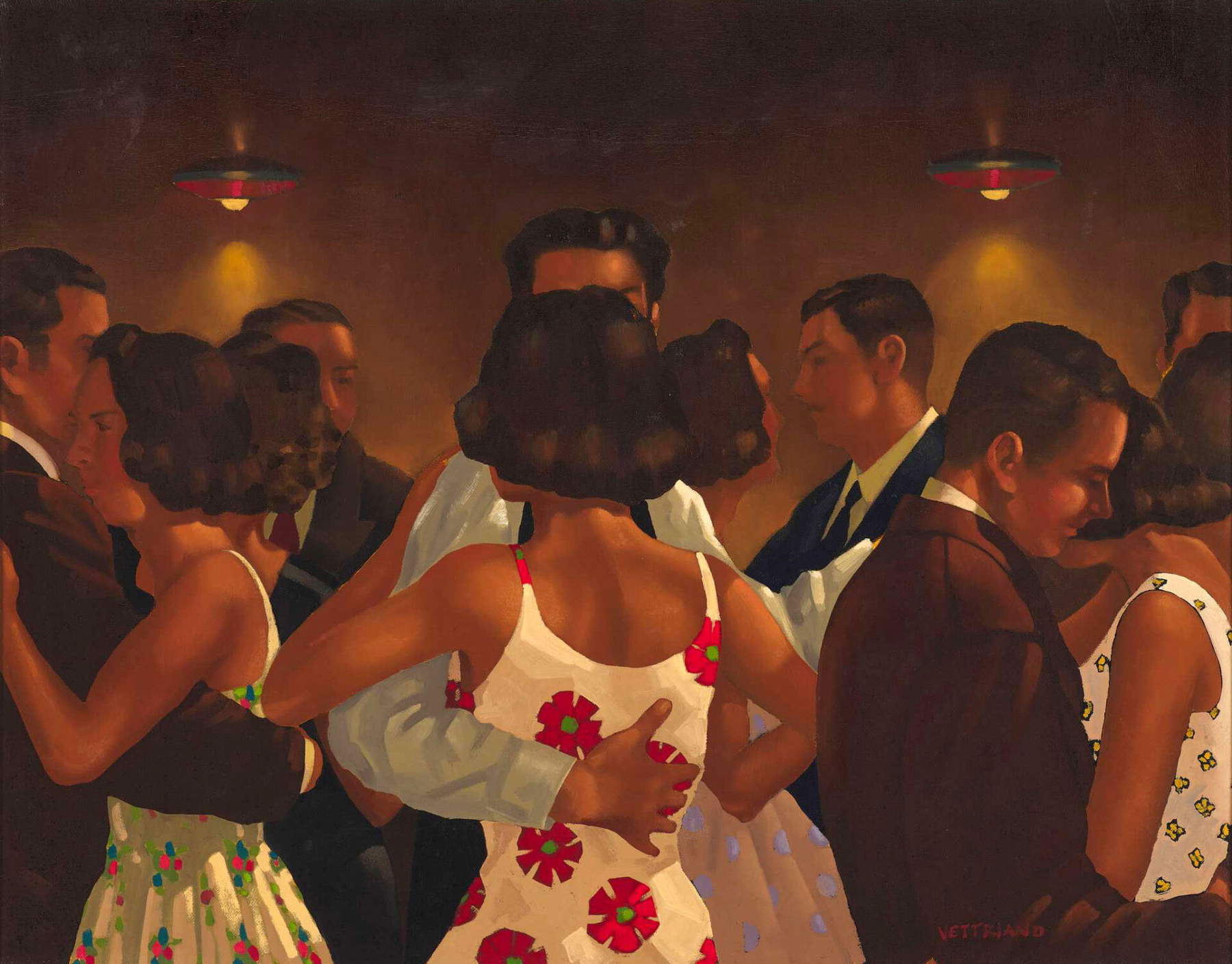

Hence the rooms, or more correctly the partitions that articulate the space, adopt titles that draw from the repertoire of jazz and sentimental song: Dream, In the Mood, Body and Soul, Dance Me to the End of Love. Each title promises and tells of a precise emotional experience, and soon after, the space intervenes and belies it. The walls remain white, aseptic, lit like a clinical corridor; the atmosphere evoked by the titles evaporates immediately, absorbed by a setting that treats the images with hygienic distance. Where the title suggests warmth, the space responds with neutrality, and where the word calls for feeling, the architecture invites detachment. The hall panels support this setting with abundant writing. The prose proceeds by accumulation of verbose and redundant images, the works float in an environment that resembles more a functional corridor than a place of thought. The graphics of the panels, on a few occasions dominated by the artist’s face and a promotional aesthetic reminiscent of early 2000s imagery, reinforce the impression of being faced with a hastily packaged product rather than a curatorial project.

Within this framework a now stabilized narrative is created: that of the artist loved by the public and viewed with suspicion by critics. Fracture is presented as an identity trait, administered as an element of fascination, cultivated as a contemporary myth. Popular consensus takes on the value of self-serving legitimacy, while critical dissent is brought back to an elitist posture, quickly dismissed as industry snobbery. In this scheme, conflict is not addressed, but neutralized. The work leaves the field of discussion and falls into the more comfortable field of preference. And this retrospective, it must be admitted, does not play in the artist’s favor.

In this context, the selfie corner reveals itself for what it is: an unintended statement of incoherent poetics. The space intended for audience participation appears bare, rigid. A photographic wall simulating an archive, an isolated easel on a worn carpet, a few images hanging as side wings. Everything concurs to construct a scene that would like to suggest intimacy and creative gesture, but returns an environment even colder, more administrative and closer to a warehouse than an atelier. The invitation to the selfie, made explicit graphically on the wall, thus enters into contradiction with the very space that should support it. The visitor is urged to pose, but finds no scene worth the pose.

This angle retroactively clarifies the entire project. The exhibition asks for participation without offering form, invokes experience without constructing a space that makes it desirable. The museum adopts the language of sharing, but misunderstands its most basic grammar: for an image to circulate, it must first exist. Here, however, the scene appears as a neutral, interchangeable backdrop, incapable of producing anything but a flat documentation of occurrence.

The selfie, rather than amplifying the visit, reveals its limitation. It adds nothing to the work, does not enrich the experience, does not generate a memorable image. It merely certifies a passage. And in this notarial, rather than narrative, function it finds its most authentic meaning.

Throughout this picture, a feeling that has hovered since the beginning becomes clear: that of images that exhaust their meaning in immediate viewing, without asking for proximity, silence, duration. Painting is quickly consumed and leaves room for the outline, the device, the relational frame. The domestic screen, with its uniform light and protective distance, appears then as a fully adequate support. The selfie, rather than a subsidence, becomes a form of unintentional critical reading. It accurately records what the exhibition really offers: quick presence, instant recognition, orderly exit.

It is in this sense that the Vettrian retrospective proves exemplary. Not as a virtuous model, but as a case study of a museography that confuses accessibility with simplification and inclusion with avoidance of thought. A mistake constructed methodically, carried out consistently, and for that very reason capable of saying a lot about how we sometimes choose to exhibit, narrate and consume art.

The author of this article: Francesca Anita Gigli

Francesca Anita Gigli, nata nel 1995, è giornalista e content creator. Collabora con Finestre sull’Arte dal 2022, realizzando articoli per l’edizione online e cartacea. È autrice e voce di Oltre la tela, podcast realizzato con Cubo Unipol, e di Intelligenza Reale, prodotto da Gli Ascoltabili. Dal 2021 porta avanti Likeitalians, progetto attraverso cui racconta l’arte sui social, collaborando con istituzioni e realtà culturali come Palazzo Martinengo, Silvana Editoriale e Ares Torino. Oltre all’attività online, organizza eventi culturali e laboratori didattici nelle scuole. Ha partecipato come speaker a talk divulgativi per enti pubblici, tra cui il Fermento Festival di Urgnano e più volte all’Università di Foggia. È docente di Social Media Marketing e linguaggi dell’arte contemporanea per la grafica.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.