Two pieces of data emerge, and extremely prominently, from the ranking of the best exhibitions held in Italy in 2025. Before going into them, however, a few details to provide the reader with a little context. Finestre sull’Arte wanted to repeat last year’s experience: to entrust the best of the Italian exhibitions that were held in the past year to a qualified jury of more than one hundred experts, including journalists, critics, curators, museum directors, professors, press offices, and various insiders, selected taking into account their experience, their geographical distribution, and the variety of their expertise. The method: a shortlist of sixty exhibitions, thirty for ancient and modern and thirty for contemporary. Each juror votes independently of all others, and may report exhibitions not on the shortlist to the editors (if there are at least three reports, the exhibition automatically makes the shortlist). A vote from 1 to 10: an average is derived, multiplied by a coefficient established to give a slight advantage to the most visited exhibitions (based on the principle that, between two exhibitions that get, say, an average of 9, more weight is given to an exhibition that got 80 votes than to an exhibition that got 40). And the ranking is drawn up. At the moment, there is no other publication that undertakes such a job: Finestre sull’Arte ’s is to date the most objective and professional end-of-year best of the year in the art sector that exists.

The first fact comes from the ancient-modern ranking: quality matters much more than name. Sure: the exhibition on Beato Angelico at Palazzo Strozzi and Museo di San Marco won, but the one on Caravaggio in Rome got only the seventh place, and the Treasures of the Pharaohs at the Scuderie del Quirinale, despite the very wide public interest and the actual extraordinariness of the exhibition (it is not an everyday thing that a significant nucleus of artifacts from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo arrive en bloc in Italy), even ended up outside the top 15 positions. Completing the podium, however, were two exhibitions on two artists little known to the general public, namely Pietro Bellotti, who earned second place, and Simone Cantarini, in third place, with exhibitions at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino, respectively. It means, in essence, that the solidity of the project is more relevant than the impact a name can make. And having seen almost all of the exhibitions that entered the top 15 places in the ranking (I am missing just a couple), it is a feeling I can confirm: the Venice and Urbino exhibitions, despite the lack of appeal of their protagonists, were built on solid scientific foundations, bringing together little-known works and masterpieces, with itineraries that are also capable of intriguing the non-specialist public. If we then add to the extraordinary quality the extraordinary element, then the first place of the Palazzo Strozzi-Museo di San Marco exhibition is explained: four years of work to bring together in Florence a significant part of Beato Angelico’s output and to design an exhibition of such density, a body of masterpieces that is unlikely to be seen again in the imaginable future, a set of international loans of the highest caliber well illustrate the reasons for the plebiscite that there was for the exhibition curated by Strehlke, Tartuferi and Casciu (a gap of almost one point in average over the second). Of course, different jurors offered different walls (not a few gave higher marks to Bellotti and Cantarini than to Beato Angelico), but on the whole this year the exhibition that combined scientific rigor and appeal to the general public won.

Interesting, then, is the composition of the type of institution that hosted the exhibition: the first fifteen positions included three state museums (two of which were on the podium), six public institutions (including municipalities and provinces), three private ones, one fabbriceria, one mixed public-private entity and one investee. It is proof, clear beyond (ir)reasonable doubt, that public museums in Italy know perfectly well how to organize relevant exhibitions, whatever they may say.

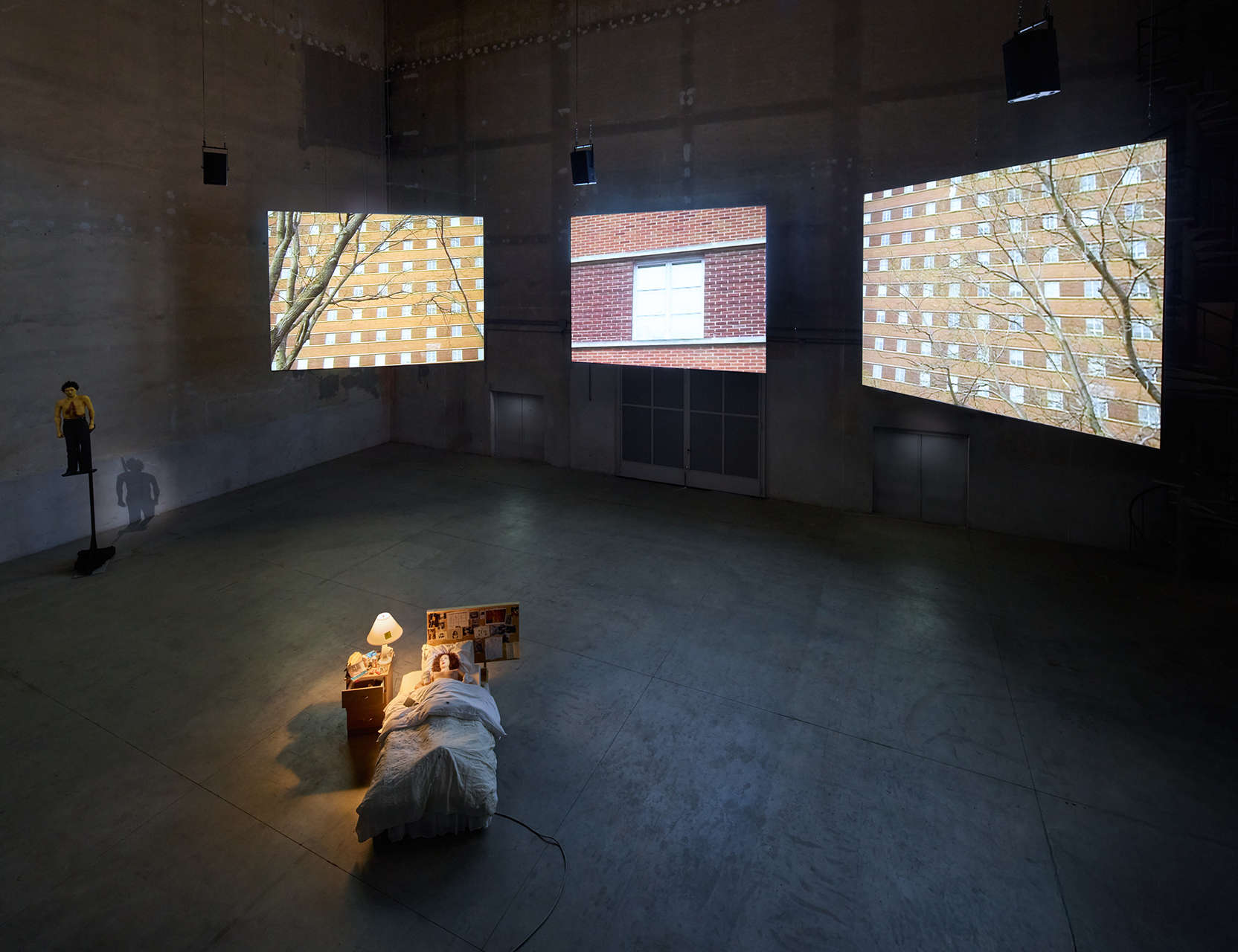

The second fact emerges instead from the ranking of contemporary art exhibitions: contemporary art, this year, was female. The 2025 podium is all female: Nan Goldin at Pirelli HangarBicocca wins, followed by Rebecca Horn at Castello di Rivoli in second place and Letizia Battaglia at Museo San Domenico in Forlì in third. And we could add Tracey Emin at Palazzo Strozzi in fourth, but that’s not all: eight exhibitions out of the first eleven in the ranking are monographs of women artists. Needless to mention that no one agreed to bring out this result (none of the jurors, we repeat, knew what the others were voting for), nor was the shortlist of thirty exhibitions selected by virtue of improbable pink quotas that make no sense for choosing a better cultural product. Quite simply, contemporary art museums offered us several quality exhibitions this year, and it just so happened that they were often projects by women artists. Or rather: not by chance. Taking a very trivial figure, and referring only to Italy (so probably not suitable to explain the ranking, which also includes international artists, but it can be a starting point for reflection), we can say that, with reference to the academic year 2023-2024, the percentage of women enrolled in a course in a fine arts academy in Italy was close to 70 percent of the total number of students (22,267 out of 32,073, data from the Ministry of University and Research). One could then broaden one’s gaze to the Art Basel and UBS Survey of Global Collecting report of 2024, which recorded 44 percent of works made by women in high-income private collections, a figure that has, moreover, been steadily increasing for many years.

Again: this is probably a fluke, since last year the same ranking was dominated by men (only one female exhibition in the top ten places). It is proof that our jurors do not look at gender (as they should): they look at the quality of the projects, regardless of the gender of the authors. However, I feel like saying that this year’s result reflects more the real dynamics of the contemporary art world, but not only that. First: because it is quite obvious that the female component in our field has a significant impact, women are really no longer a minority as they were until twenty to thirty years ago or maybe even more. Of course: it is a truism, a platitude. But it is good to reiterate it. Second: one might borrow the words of Pilar Corrias, owner of the London gallery of the same name, one of the most participatory and interesting on the world scene, who last year, commenting on the results of the Art Basel survey , recalled that “a massive canon correction is taking place and institutions are working hard to catch up.” On the one hand, therefore, a greater attention to women’s art, which, however, I would like to say, I think is a natural reflection of women’s participation, evidenced by the percentages of female students enrolled in academic courses (we cited Italian data, but I think if you look at the rest of the Western countries the numbers are not so dissimilar from ours), by the amount of galleries opened by women all over the world (just take a trip to some fair, even in Italy, paying attention especially to international participations, to get an empirical idea), by the exhibitions and projects of women artists. With the hope that finally, in a few years, we will no longer have to think in terms of quotas and percentages, because it will mean that everywhere we will have achieved true parity, that parity whereby it will be possible to evaluate projects everywhere regardless of the gender of those proposing them. One hundred years from now, hopefully, scholars of the future will not have to continually invent exhibitions on Artemisia Gentileschi or Frida Kahlo to fill in gaps: they will find that women were a natural, and even majority, component of the twenty-first-century art scene.

Not everything is positive, however: there is still a significant gap between the votes given to the ancient-modern and the votes given to the contemporary. This is not because the jurors of the contemporary are tight-lipped, while those of the ancient are inclined to turn a blind eye. It is a dynamic that is identical to last year, although this year there are on average higher votes, and it is a symptom of the fact that contemporary exhibitions in Italy suffer from a certain backwardness compared to those of the ancient. In other words, exhibitions of contemporary artists are perceived as less valuable, less interesting than exhibitions of ancient art. And if Italy is perhaps the world’s leading power for exhibitions of ancient art (or at least we come close), the same cannot be said for contemporary art exhibitions; on the contrary, whether it is because of the weakness of the offer, or because of the lesser relevance of Italian artists compared to foreign artists, or because of the lack of a strong criticism, or because of the poor vision of many curators, we are struggling on the contemporary scene. But it is also true that, compared to last year, quality is on the rise. We shall see what interesting things this 2026 has in store for us.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.