There are figures who, more than others, traverse art history as ambivalent presences, somewhere between the generosity ofthe patron and the rigor of the banker. Figures who do not create, do not paint, do not sculpt, but without whom much art would never have existed, and much else would have been lost in the void. These figures are the collectors.

The collector is, at once, a savior and a jailer. Savior because he buys when no one buys, because he takes risks when the market has not yet decreed a value, because he sees where others do not see. Jailer because at the very moment he buys a work, he takes it away from the world: no longer a collective patrimony, but a private good. The tension between these two poles, rescue and subtraction, runs throughout the history of collecting, from Renaissance galleries to contemporary foundations. And today, more than ever, we need to ask: Is it fair that art belongs to a few? Is it fair that a work that was created to speak to the world should end up locked away in a vault, invisible to those who cannot afford to cross the threshold of a private home?

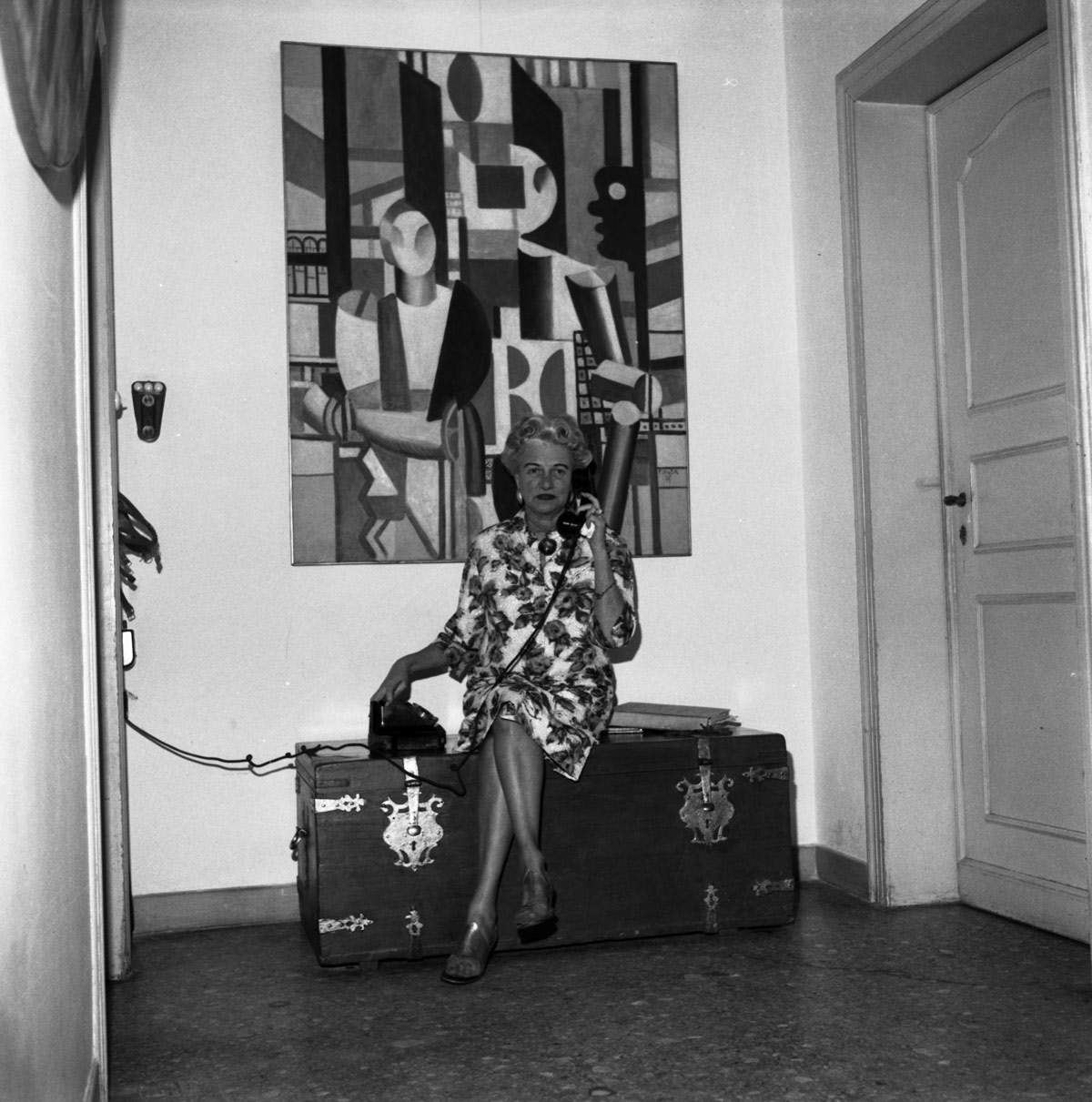

History gives us many examples in which the collector played a providential role. Lorenzo de’ Medici was not only an astute politician: he was the one who recognized in a young Michelangelo a talent to be supported, granting him the space to grow. Isabella d’Este, with her collection in Mantua, shaped a model of the “studiolo” that still fascinates us today. Peggy Guggenheim, in the twentieth century, saved entire generations of American and European artists by buying works that no museum wanted and turning them, over time, into indispensable masterpieces. The collector, in these cases, was the one who believed before the work became famous, the one who guarded when the public institution did not have the means, the one who passed on when others would have forgotten. Without collectors, most likely, entire art movements would have left no trace.

But there is the other, darker side. Whenever a work enters a private collection, it leaves, at least in part, public life. It is no longer freely visible, it can no longer be easily studied, it no longer belongs to the common heritage. Many Italian Futurist works, for example, were sold abroad in the 1920s and 1930s, when Futurism did not yet enjoy strong institutional recognition. Many paintings by Boccioni and Severini ended up in foreign private collections, and some were even lost. The same fate befell works by Burri, Fontana, and Manzoni in the 1950s and 1960s, purchased by far-sighted private individuals and then disappeared behind closed doors.

They were not destroyed: they are alive, guarded, insured. But invisible. And an invisible work is, in a way, a mutilated work. Because art lives only in the gaze of the beholder, only in the community that interprets it. If a painting hangs in an inaccessible living room, its voice dies out, or rather: it shrinks to an infinitesimal audience. And here the contradiction emerges: art is both object and language. It is matter that is bought, sold, owned. But it is also a collective voice, a testimony of a time, a universal narrative. To treat it like any other good, like land, a villa, a piece of jewelry, is to reduce it to a commodity. But at the same time, to deny the possibility that it is private property is to ignore that without the economic support of private individuals, much art would not exist.

Contemporary collecting oscillates between these poles. On the one hand, the large collections open to the public, Pinault in Venice, Prada in Milan, Rubell in Miami, which have transformed private assets into places of collective enjoyment. On the other, thousands of works locked in vaults, treated as financial assets, traded at auctions like securities on the stock exchange. It is the same work that, depending on its fate, can be “saved” or “seized.”

The question then becomes an ethical one: does a work of art really belong to the person who buys it? Or, in the very moment it comes into being, does it also belong to the community that recognizes it as a testimony? A Caravaggio in a public museum is part of our national identity. A Burri in a private collection should be perceived in the same way. Yet the latter is taken away from the eyes of the public, reduced to an investment, a symbol of status. Is this legitimate? Yes, in law. But is it right, culturally?

We must not, however, demonize the collector, but redefine his role. No longer a solitary jailer, but a sharing custodian. No longer absolute master, but part of a social pact that recognizes art as a common good, even when it is privately owned. Some tools already exist: long-term loans to museums, tax incentives for those who open collections to the public, accessible digital archives that document works, even when they are not physically visible. But more needs to be done. A change in mindset is needed: understanding that the true value of a work is not in its price, but in its ability to speak to many.

A work locked in a vault, invisible, is like a book that no one reads, like music that no one listens to. It lives, yes, but in what way? Perhaps collectors really are the big players incontemporary art, but the judgment of their actions depends on this: on how willing they are to let the works they guard continue to live, to circulate, to be looked at. Because, after all, the question we need to ask ourselves is no longer just who owns the art, but who can see it. And on this answer depends not only the fate of private collections, but the very vitality of our culture.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.