A three-story mansion overlooking the Grand Canal, opposite the Fabbriche Nuove del Sansovino. It is called Palazzo Bolani Erizzo and from its windows, if you look to the left, you can see the Rialto Bridge. In the sixteenth century Pietro Aretino lives there, and one day, it is May 1544, he is standing at his window sill, contemplating the sunset over Venice. He watches the boats plying the Grand Canal. Two gondolas that seem to be competing in rowing. The crowds watching the regatta. He turns toward the Rialto Bridge. The amazement, the wonder of human beings before the setting sun crosses the centuries, and that day amazement crosses the mind and eyes of Aretino, who after admiring that spectacle decides to write to Titian, his friend, to tell him that that sight had reminded him of his paintings: “I turn my eyes to the sky; which since God created it has never been embellished by so vague a painting of shadows and lights. Hence the air was such as those who have envy of you would wish to express it, for it cannot be you, whom you see in telling it I. [...] Consider also the wonder that I had of the clouds composed of condensed moisture, which in the principal view were half standing, close to the roofs of the buildings, and half in the penultimate, since the starboard side was all of a gradient hanging in blackish gray. I was certainly astonished at the varied color of which they showed themselves; the nearer ones blazed with the flames of the solar fire; and the farther ones reddened with a not so well kindled ardor of minium. Oh with what beautiful hatching the natural brushes thrust the air thence, discerning it from the palaces with the manner that Vecellio discerns it in the making of countries! [...] O Titian, where are you now? By my fe’ that if you had portrayed what I count you, you would induce men in the amazement that confounded me; that in contemplating what I counted to you I nourished the soul that no longer lasted the marvel of so made painting.”

Aretino’s wonder is identical to that which many still feel now in the presence of a sunset, a nature, a panorama. The only difference is that Aretino needed a few sheets of paper to express those feelings at seeing the last sun tint the water and sky of Venice. We, on the other hand, manage it in three words. It happens when we stop and look at a landscape, a pleasant landscape, a landscape that conveys some emotion to us. And we say that “it looks like a painting.” Or, at most, that “it is as beautiful as a painting.” And it seems like an automatic reaction to us. But, in fact, it is much less so than it seems. Why is it that when we see a landscape that we feel something for, we say that “it looks like a painting”? Francesco Bonami even used this exclamation as the title of one of his recent popular books. He says that once upon a time we would have said that a landscape “looks like a postcard” (we still say it, and we will say it as long as there is anyone old enough to preserve the memory of when we sent postcards to friends from vacation spots), and that today we say that “looks like a painting” because we are overwhelmed by a flood of artificial images and therefore, when faced with something we cannot tame, we end up seeking refuge in a reality that is equally artificial, but more familiar: that of the painting, precisely. Actually, the idea of wanting to trace nature back to culture is not new, nor does the term of comparison with the product of an artist’s work depend on the degree of familiarity we have with that object. In 1901, Federico De Roberto, in one of his books on art, also rather ambitious, in order to ask what are the things that we consider beautiful started from our own example: “In the countryside, before a graceful or grandiose landscape, we say that it looks like a painting; and if we catch flowers or stupendous fruits we repeat that they look like paintings.”

There is, meanwhile, an interesting thing to start with: to refer to a glimpse of nature, or even a glimpse of a city (let us define the concept of “landscape” in an extremely crude and brutal way for now), we use a term, “landscape,” which originally identified a work of art in which the artist had depicted ... a landscape. It has sixteenth-century origins: it seems to have originated in Fontainebleau where, in the 1630s, the King of France, Francis I, had called a number of Italian artists (Rosso Fiorentino, Francesco Primaticcio, Luca Penni, and other less famous ones) to decorate the monumental rooms of the royal castle, and who would use it among themselves, along with their French colleagues. The lemma paysage is then recorded in 1549, for the first time, in the Dictionnaire of Robert Estienne, who includes it in his vocabulary, calling it a “common word among painters”: in all likelihood it derives from Italian, since it was then usual to call a painting depicting a laceration of territory “paese,” a genre that, moreover, had recently been born. In any case, it is curious to note that even before the appearance of the term “landscape” there was a word that referred to both the real and the artificial element. And it is only later that the word that was used to refer to a painting knows an enrichment of its meaning and finally becomes the term that defines the appearance of a territory, typically that piece of territory that extends as far as the eye can reach. “Part of a territory that is embraced with the gaze from a given point,” says the Treccani dictionary today. Again: the human being as a measure of nature. Superfluous, however, to reiterate that “landscape” does not mean only the natural one, but also the urban one, since the constituent elements change (thus buildings, roads and architecture in place of mountains, rivers, trees and the sea), but the way in which one sees the environment does not change.

We return, therefore, to the time when “country” identified both the geographical dimension and the artistic dimension. And it is so in all Latin and Anglo-Saxon languages, despite the etymological differences: landscape, paysage, paisaje, landscape, Landschaft, landschap. Whether they originally refer to the human element or the natural element, they all end up adding up the two dimensions. In all of them there is this duplicity, this ambiguity, this overlap. Moreover, in Italy, one of the first to “introduce,” so to speak, the new term, is Titian himself, in a letter sent on October 11, 1552, to Philip II of Spain, in which the artist tells the sovereign that he has sent him some of his works: “il paesaggio et il ritratto di Santa Margarita, mandarevi per avanti per il Signor Ambassador Vargas.” The painting mentioned by Titian is the first in the history of painting to be called a “landscape.” The problem is that we do not know which one it is: no paintings by Titian of only landscape have come down to us. What is important, however, is to know that this ambivalence, this artistic origin of the term with which we even now identify a piece of the land, has in a way conditioned the way we observe what surrounds us.

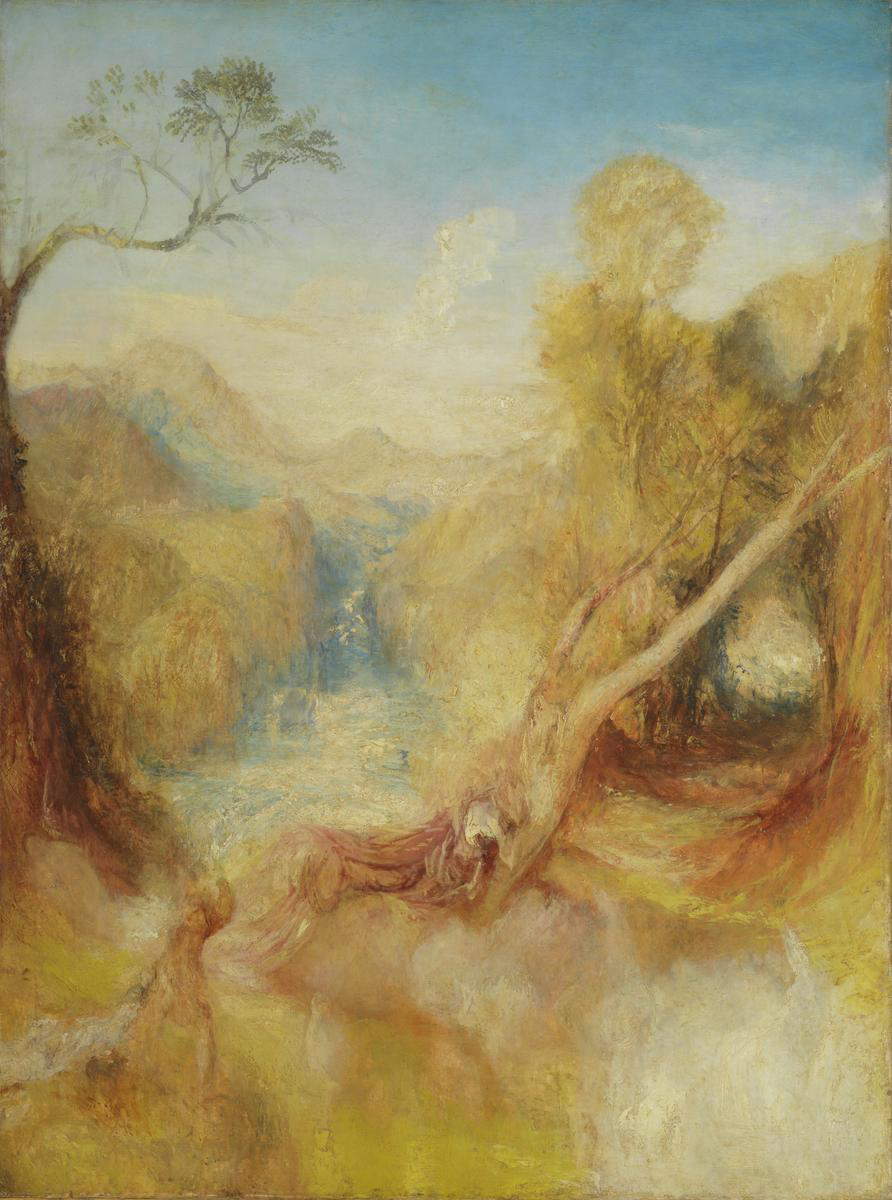

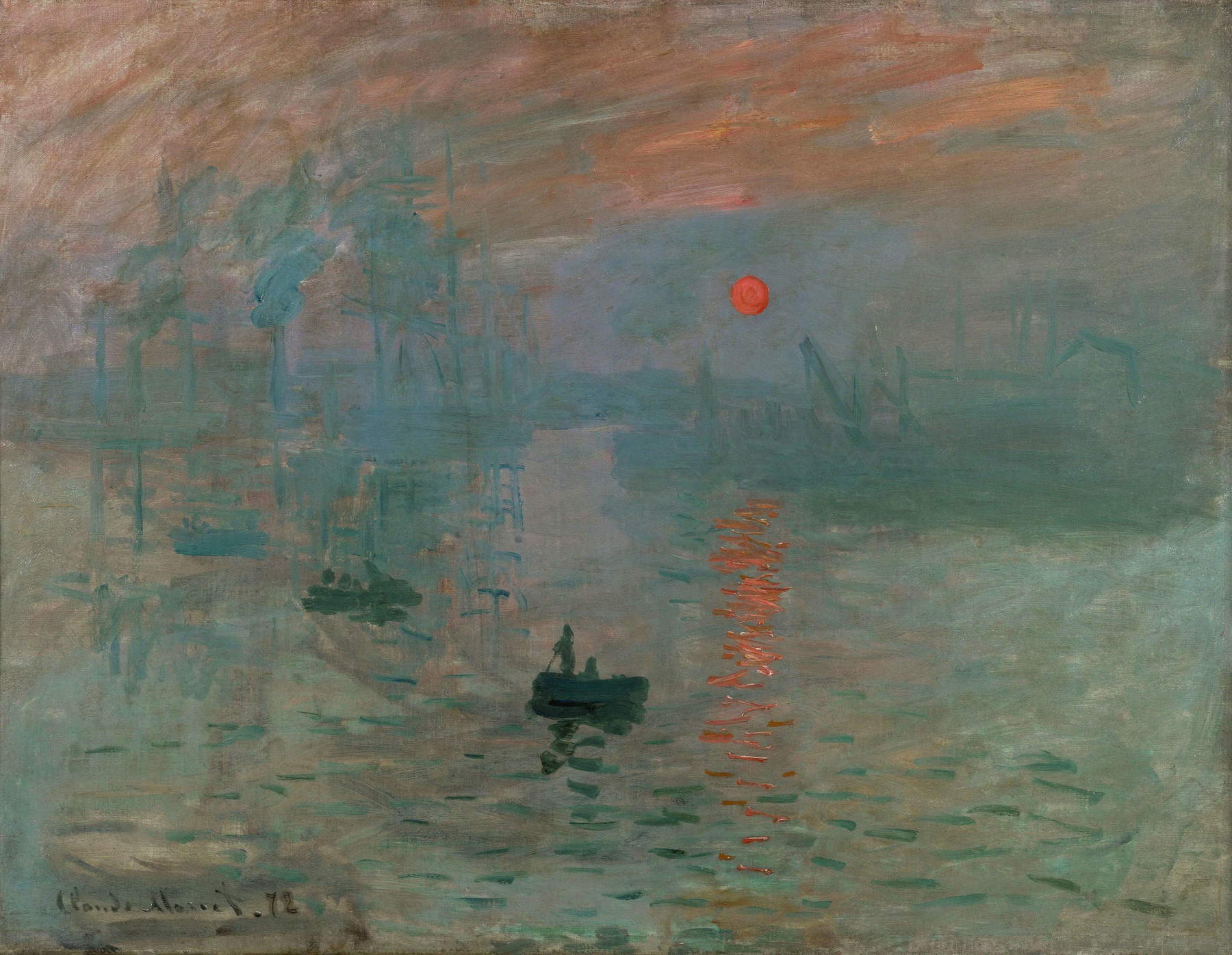

For centuries, the real landscape has been “perceived and conceptualized as the projection onto nature of what painting has taught us to see,” writes Paolo D’Angelo, a scholar of aesthetics. We then appreciate the Roman countryside because we know Lorrain’s paintings. We associate the Tuscan countryside with certain recurring elements because we have seen the landscapes of Piero della Francesca, Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci first and then the Macchiaioli. We have an idea of the surroundings of Paris because we remember the paintings of the School of Barbizon and the Impressionists. We feel the fascination of the fog because we saw Turner’s paintings, that of the mountains because we saw Segantini’s paintings, that of the sea because we saw Fattori’s and Nomellini’s paintings. And it is interesting because the assumption holds true even for those who in their lives have never seen a painting by Lorrain, Piero della Francesca, Théodore Rousseau, Monet, anyone: it is not a question of art knowledge. The point, probably, is that artists shaped a taste that has since become a common feature of our approach to landscape. One internalizes a way of seeing nature that has arisen and spread through art. Giving an iconic written form to this idea, with the irony that has always distinguished him, was Oscar Wilde, who in one of his dialogues, The decay of lying (“The decay of lying,” 1889), puts into the mouth of one of the characters, Vivian, the thesis of the gaze educated to see nature by means of art: “Where, if not from the Impressionists, do those wonderful brown mists come from that creep into our streets, blurring the gas lamps and turning houses into monstrous shadows? To whom, if not to them and their master, do we owe the enchanting silvery mists that loom over our river and turn into faint shapes of faded grace, curving bridges and swaying barges? The extraordinary change that has taken place in London’s climate in the past decade is entirely due to this particular school of art. Smile. Consider the matter from a scientific or metaphysical point of view and you will find that I am right. Because, what is Nature? Nature is not a great mother who begat us. It is our own creation. It is in our brain that comes to life. Things exist because we see them, and what we see, and how we see it, depends on the Arts that have influenced us. Looking at something is very different from seeing it. You don’t see anything until you see its beauty. Then, and only then, is it born. Nowadays, people see fogs, not because they are there, but because poets and painters have taught them the mysterious beauty of such effects. Perhaps there have been fogs in London for centuries. I dare say there were. But no one saw them, and so we know nothing about them. They did not exist until Art invented them.” Wilde, in essence, was giving a theoretical form, however seemingly paradoxical, to the feelings that Aretino confessed in his letter to Titian.

It is indisputable that, over the centuries, painting has provided us with eyes to look at landscapes, albeit with all the changes in taste and orientations that history has gone through. This kind of knowledge then settled and became a kind of collective heritage, which marked the ages (it is impossible to imagine the Europe of the Grand Tour, the Europe of the ruling classes who were formed by chasing the myth of classical antiquity, without resorting to the landscape painting of the time: for most, perhaps even for all those who set out for Italy and Greece, the first spark was ignited by a work of art) and even directed political choices: still in 2004, the Cultural Heritage Code identified as “landscape assets” of “considerable public interest,” in Article 136, those “scenic beauties considered as paintings”, wording that was derived from the 1939 Bottai Law, Italy’s first protection law, where the wording was identical (the only difference was the use of the expression “natural pictures” instead of “pictures”). The 2009 update then eliminated the words “considered as pictures,” but did not do away with the idea that protection acts on the aesthetic value of the land: the Council of State has also expressed itself on the issue in these terms, stating that the elimination of the reference to the beauties “considered as pictures” does not make the equivalence between the view of “scenic beauties” and the view of “natural pictures” lapse.

The example of the Cultural Heritage Code is useful because the 2009 update was probably also intended to bring the legislative instrument into line with overcoming what we might call the “artistic theory of landscape,” (although, in fact, case law shows that at the very least the interest of’a sliver of land is still assessed on the basis of aesthetic assumptions), given its obvious conceptual limitations, and given that, at least since the 1970s, the idea of landscape has progressively lost importance in favor of the idea of “environment,” a radically different concept, since it is pertinent to the scientific dimension of what surrounds us, and not to the contemplative or cultural dimension. Landscape versus environment, then. Aesthetics versus science. But it would be reductive to reason in these terms, since in the last forty years the very concept of “landscape,” as will be seen a little later, has expanded. More importantly, this does not mean that we have stopped talking about landscape in contemplative terms. It has been seen: the Italian law expressly protects landscape assets, understanding landscape according to an updated vision compared to the one that takes into account only the contemplative dimension of what we see, that is, as “the territory expressive of identity, whose character derives from the action of natural, human factors and their interrelationships.” This new idea of landscape, which has emerged since the 1970s, is the child of the reconsideration of the artistic theory of landscape, which had appeared reductive. One wondered, for example, how the early artist could have seen nature, not having his taste trained on that of others who had filtered the environment before him. Or, one wondered in what way the existence of a perception of the surroundings that is not conditioned by art, by painting, could be given. The answer that has been given, said in a somewhat crude but perhaps effective way, is that the landscape is not only space to contemplate, but it is space to live in, it is space in which human beings have lived and in which they will continue to live. And being a space to be lived in, landscape cannot disregard the action of human beings: landscape is, in essence, a place where the values of societies and communities are read, their history, the way communities have related to nature, even their future. It is lived, charged, dense, historical, layered space. Rosario Assunto, for example, in his 1973 book Il paesaggio e l’estetica (The Landscape and Aesthetics ) tried to overcome the idea of the landscape-frame by attempting, meanwhile, to distinguish between the contemplation of nature and that of art and arriving at the hypothesis that the pleasure of nature is physical pleasure and that of art is pleasure of the beautiful (a pleasure of the beautiful that is then reflected in nature as it is self-contemplating, “and thus in the contemplation of self becomes disinterested, thus acquiring the unconditionality and universality of the beautiful”), and then elaborating a concept of landscape as a “place of memory and time.” “epochs and events, institutions and beliefs, customs and cultures [...] become simultaneous in the spatial image [...], in the capacity they have to restore in the heart of the present, and without modifying the present, all the past.” To a not so dissimilar conclusion would come, in the 1980s, Alexandre Chemetoff, for whom the landscape is “the moving trace of civilizations, which suddenly reveals itself to the gaze in a single place, where what has happened, what is happening and what will happen is intertwined.” The idea of a landscape as the sum of the relationships between human beings has since informed the idea of landscape as formulated in the UNESCO convention, which defines landscape as “theformal expression of the multiple relationships existing over a given period between an individual or society and a topographically defined space, the appearance of which is the result of the action, over time, of natural and human factors and their interrelation.”

Obviously, it would be impossible to postulate, at least as far as the experience of us Westerners is concerned, the existence of a nature that is not touched by human hands, or at least that is not filtered through any sensibility of cultural character. There is no longer a total communion between man and nature: that “laceration” of which Georg Simmel spoke as early as the nineteenth century has now been consummated for centuries, a laceration that has entailed an awareness on the part of the human being, who has become aware that he is a unit separated from the infinite totality of nature. And this is fundamentally the reason why, when we leave our homes and look around, the landscape we observe may appear to us as a painting. Even if we have never seen a painting in our lives, and even if a landscape has its own specific dimension and has characters that are unknown to the work of art. Meanwhile, because a glimpse of nature and a glimpse of a city are always objects of contemplation. We may have never seen a painting, and pull out, perhaps almost automatically, a smartphone to frame a seaside sunset with the camera, and perhaps post it on Instagram: we are looking for nothing more than a painting (and, one might say, we are still Oscar Wilde’s children). Also, because we live in a civilization in which relationships between nature and culture have always, invariably, inevitably existed: the space in which we move, the elements we encounter when we explore an area, whether it is our city or whether it is a space unfamiliar to us, the relationships between the proportions, colors, light and shadow that giveshape our cities are always the inescapable product of a human hand, and it is therefore sensible, understandable, logical that along the span of our existence we form, more or less consciously, a gaze accustomed to human measure. Culture is also determined by the alternation of sensibilities that have been formed with the contribution of artists and that have come to condition our relationship with nature. Without even going into the concept of “beauty” and how it has changed over the centuries, it can be said that even those who have never set foot in a museum possess a cultural gaze. Our relationship with nature is no longer natural: it is mediated by this collective cultural heritage. And that is why, when we contemplate a landscape, the most spontaneous association of ideas leads us to imagine a painting.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.