The cultural interaction between Etruscans and Greeks, in what is referred to as Hellenistic Etruria, represents one of the most significant phenomena of antiquity, which left a profound imprint on art, religion and social organization. Indeed, Etruria becomes, in this period from the years between the turn of the 4th-3rd centuries B.C. to the 1st century B.C., a true meeting point between the two cultures. The relations between the Etruscans and Greeks were the result of intense trade exchanges: through these relations, the Etruscans made various aspects of Greek civilization their own, yet inserted them into a context that remained firmly Etruscan, thus without losing their identity. Necropolises and archaeological finds still constitute tangible evidence of this relationship and provide valuable information on the development of Etruscan society, as evidenced also by the head of a maiden (a Kore) recently found at Vulci, an example therefore of Greek sculpture found in Etruscan territory.

Archaeological investigations show how Etruscan society went through a complex transformation. Analysis of the necropolises highlights the transition from a relatively uniform community to a stratified society in which a powerful aristocracy emerged. At the same time, Etruscan urbanization proceeded with the founding of new centers and the expansion of existing settlements. This urban development is indicative of the growing ability of elites to control territories, activate trade networks and promote craft activities.

The expansion of the economy also entailed a more articulated division of labor, evident in the stages of object manufacture, characterized by the increasing entry of servile labor and a growing uniformity of production. In the Hellenistic age , Etruria appears as a large and complex production system, in which numerous specialized centers operate. Prominent among them are those in the interior linked to the Tiber valley, such as Volsinii, Falerii Veteres, and Chiusi, and those in northern Etruria, such as Volterra. In contrast, the cities of southern Etruria sought to maintain a competitive role and distribute their manufactures by taking advantage of their territorial and cultural proximity to Rome. It seems that influences between different cultures were exerted mainly through two ways: on the one hand, the impact of imported artifacts on local artisans, and on the other hand, the arrival of technicians and artists from different regions of the Mediterranean, bringing technological skills and figurative repertoires. Let us now look at a few examples.

In red-figure ceramics, in addition to the reference to Greek and Magna Graecia models, evident especially in the plastic vases, we note the presence of iconographic motifs also widespread in Greek and southern Italian toreutics and glyptics, such as scenes of ferocious animals slaughtering defenseless prey, which are well known thanks in part to the François tomb at Vulci, the monumental hypogeum built by the Vulcian Saties family in the second half of the fourth century BCE.C. that was discovered in 1857 by archaeologist Alexander François, after whom it is named. The tomb consists of seven burial chambers arranged around an atrium and tablinum, the walls of which were decorated with an extensive cycle of frescoes. These, detached in 1863 at the initiative of the Torlonia Princes, are now in Rome, in the Torlonia Collection at Villa Albani. His figurative program combined characters from Greek mythology with elements from the Etruscan world.

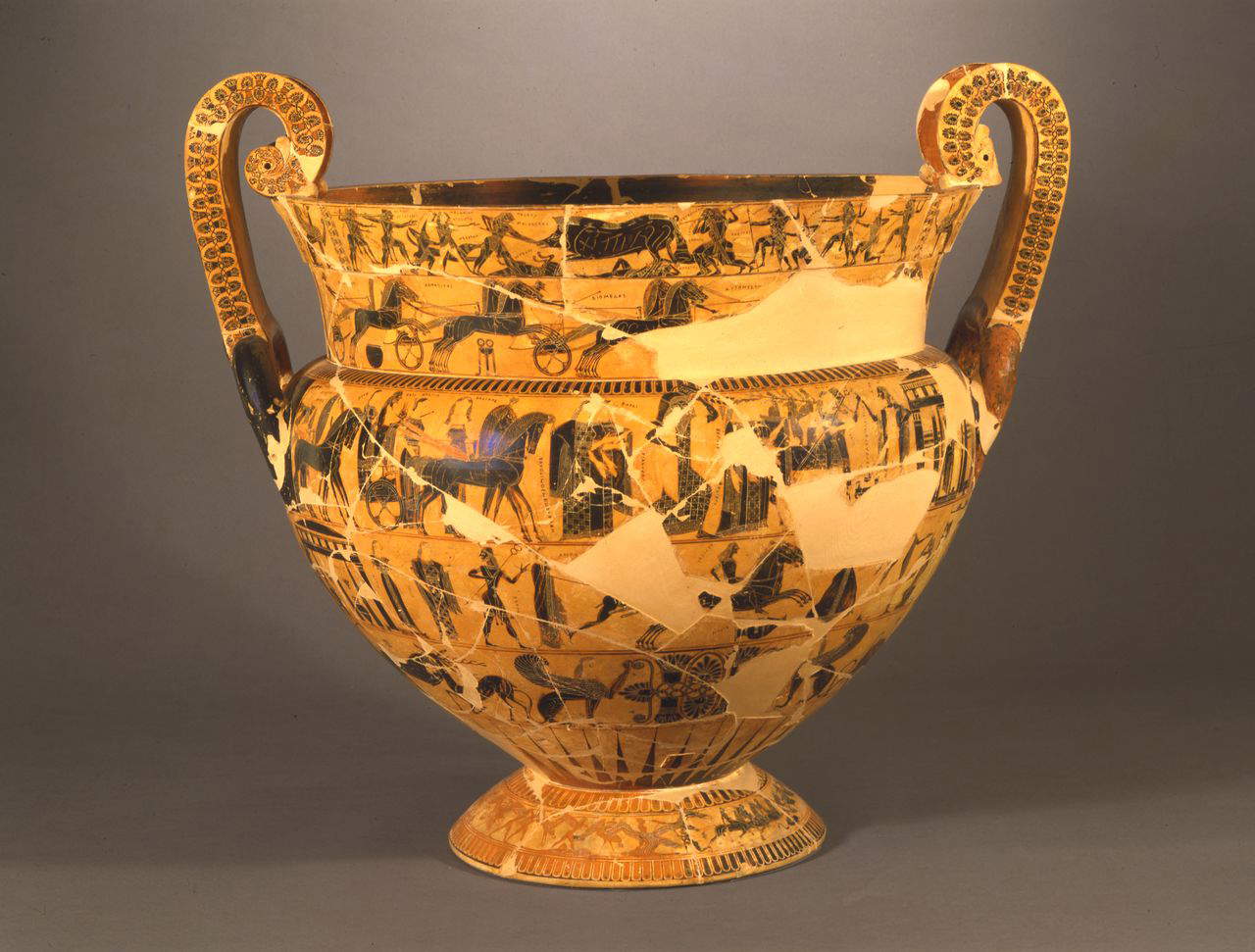

Alexander François himself also discovered the famous François Crater, nicknamed the King of Vases because of its monumentality and its decoration with a mythological theme (in the main frieze, the procession for the wedding of Peleus and Thetis), a masterpiece of Attic production with black figures preserved in the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. The volute crater, on which the names of the potter Ergotimos and the painter Kleitias appear, was found in fragments in the area of two Etruscan tumuli at Fonte Rotella, near Chiusi, in 1844-1845 and was reconstructed by restorer Vincenzo Monni. As for black-glazed pottery, on the other hand, the workshops of inland northern Etruria, particularly the production of the Malacena, show relief decorations and surfaces with a metallic effect, clearly inspired by metal prototypes from the Greek and Magna Graecia worlds.

Among the Hellenistic-era manufactures, urns also assume great prominence. Productions from Chiusi and Volterra feature Greek mythological themes and funerary iconography made in workshops in which stylistic influences from Pergamum, Rhodes, and the Atticist milieu are particularly evident. In Volterra alabaster and tuff and in a few cases terracotta are used, while in Chiusi local alabaster, travertine, and terracotta are used. The innovations of the Middle and Late Hellenistic periods are attributed to the work of Hellenic-trained artisans, while in the early second century B.C. the works of the so-called Master of Oenomaus introduced new compositional patterns and an intensity of expression reminiscent of the Parchment tradition.

In Tarquinia, from the mid-4th century BCE, marble or travertine sarcophagi were made, works by Hellenized craftsmen and intended for high-ranking patrons, alongside cheaper specimens in local stone. Between the mid-fourth and early third centuries B.C.E., a frieze with fighting animals, a figurative scheme also very common in Greek and Magna Graecia pottery and toreutics, became widespread on the long sides of sarcophagi. In Chiusi, on the other hand, mythological scenes and imposing Galatomachiae (depictions of fights between Greeks and Galatians) dominate, harking back to late-classical and early Hellenistic models.

Regarding mirrors, the theca type, akin to Magna Graecia and Macedonian examples, became widespread in this period. This model, developed in Greece as early as the end of the fifth century BCE, then spread to both Ionia and Magna Graecia, resulting in specialized production. Etruscan craftsmen also readily transposed this new type.

In the social practices of the Etruscan aristocracy, the banquet-symposium became one of the most representative elements. The banquet represents one of the central moments of Etruscan social life, just as it did in the Greek world from which this practice is borrowed. It is an occasion that also serves as a sign of prestige, since it attests to membership in the upper levels of society. During such banquets, numerous ceramic and bucchero vessels are used on the table, mostly produced in local workshops. Alongside the more common pieces such as bowls, plates, and pitchers, forms taken from the Greek repertoire also appear, including the two-handled cup, the kylix, intended primarily for the consumption of wine.

The information that Etruscan culture has transmitted to us directly about banqueting and symposia comes almost exclusively from material found in funerary contexts. This forces us, with few exceptions, to view such practices through the lens of the tomb world. One example is the Tomb of the Leopards in the Tarquinia Necropolis, dated 473 BCE. This is a rectangular chamber tomb whose name is due to the depiction of two leopards depicted with their jaws wide open around a tree in the trapezoidal space in front of the entrance. The symposium depicted takes place outdoors among olive trees, and young naked servants bring meals to men and women who appear to be lying on triclins. Thus, the image that the Etruscans themselves chose to leave behind emerges in the funerary context: a representation in which the banquet becomes a symbol of aristocratic life and a privileged moment of relationship and social cohesion. This conception is reflected in the grave goods laid in burials, which can be interpreted as intentional manifestations of the wealth possessed in life and as a form of ostentation of one’s rank.

With regard to religion, among the deities worshipped by the Etruscans is the god Culsans, guardian of the gates and cycles of time, depicted two-faced looking simultaneously inward and outward, thus we might say by extension toward the past and the future. His iconography developed in a context in which similar figures were already present in other cultures. In Greece, in fact, Argos, the two-faced guardian, appears as early as the Archaic age, while in Rome, in the same period, the Archaic image of Janus is defined, also represented with two faces and a long beard, an obvious reworking of the Greek model of Argos.

With the Hellenistic age, the renewed iconography of Argos seems to exert a further influence on that of Janus, who begins to be depicted with a short and curly beard, or sometimes without a beard. The figure of Argos also spread to Etruria in the fourth century B.C.E., though he retained his original characters. The oldest visual evidence of the god Culsans found in Etruria dates precisely from the Hellenistic period: these include the bronze statuette from the Porta Ghibellina in Cortona, now housed at the MAEC in Cortona, which is the only full-length image of the Etruscan deity, and bronze coins from the city of Volterra on which two-faced juvenile heads are depicted (it should be considered how coins of the 3rd century are no longer of gold or silver, but only of molten bronze, and are mostly issued from centers of mining importance such as Tarquinia, Vetulonia, Populonia and Volterra, but above all it is important to specify how the depictions on them are true indications of the cults practiced in the issuing centers, such as the two-faced head on the Volterra coins, or of the activities that took place there, such as the blacksmithing tools on the Populonia coins). The National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome, on the other hand, holds two terracotta heads, from the North Gate of Vulci, molded and finished by hand depicting a two-faced deity with a full beard; the National Archaeological Museum in Florence also holds a black-paintedoinochoe , a Janiform vase characterized by a peculiar headdress made from the skin of a ram’s head, attributable to the Malacena factory, thus of Volterran production.

AGreek-inspired Etruscan masterpiece depicting a deity, this time a female one, is the Minerva of Arezzo, now in the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. Made of hollow bronze and created in the first decades of the third century B.C. using the lost-wax technique, the goddess of wisdom and war is depicted with her helmet raised on her head, her aegis with the gorgoneion on her chest, and her long chiton reaching down to her feet. It owes its name to the city where it was discovered, Arezzo, in 1541, near the church of San Lorenzo; it was acquired in the collection of Cosimo I de’ Medici for use in the Studiolo di Calliope in the Palazzo Vecchio.

The Greek demigod Heracles, famous for his strength, is also received in the Etruscan world as Hercle, as evidenced by the Piacenza Liver, the bronze model of a sheep’s liver with Etruscan inscriptions dating from the period between the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C. now housed in the Palazzo Farnese in Piacenza, on which the name “herc” is inscribed. Several bronzes depicting him can be seen at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence, always wearing a leonté (the skin of the Nemean lion he defeated) and armed with a club that he holds raised. In some cases, as in the engraving on a mirror from Volterra, he is depicted according to a completely Etruscan myth, namely suckled by the goddess Uni.

Ultimately, these exchanges not only enriched the social and artistic life of Etruria, but also contributed to the formation of a complex and original cultural identity, capable of harmoniously combining Etruscan and Greek elements.Hellenistic Etruria thus appears as a dynamic territory, open to outside influences but firmly bound to its own traditions.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.