The National Archaeological Museum of Civitavecchia reopens with totally new layouts. And this revision work to which both the rooms and the storerooms have been subjected has reserved a surprise for the archaeologists and staff engaged in the updating of the exhibition, coordinated by director Lara Anniboletti and archaeologist Alessandro Mandolesi. In particular, the reconnaissance in the storerooms made it possible to rediscover inside a box confused among numerous stone materials, three important fragments in Greek marble, almost forgotten, belonging to one of the most beautiful and valuable statues in the museum.

To learn about the history of this sculpture, a splendid Apollo from the 1st-2nd centuries AD, one must go to the ground floor of the museum, where an important selection of Roman sculptures from the area of the Trajan port of Centumcelle and the luxurious seaside villas that were located along the coast north of Rome are preserved. These were pleasure residences that featured a scenic layout of rooms and overlooked the sea, sometimes with attached fishponds. They belonged to personalities from the political and cultural world of theUrbs: among them is the villa attributed to the jurist Ulpianus, who lived in the third century A.D., one of the founders of Roman legal doctrine, the remains of which were identified in the nineteenth century in Santa Marinella, at the promontory of the Odescalchi Castle overlooking the town’s small port. Ulpianus, in addition to being a fine writer and lover of literature, was evidently also a devotee of the great Greek art of the Classical and Hellenistic ages, if from his villa come several Greek marble replicas of famous ancient sculptures, which were to embellish the spaces he cherished, and which are now exhibited in various European museums. Such as Dionysus and Pan of Praxitelian type, a Meleager attributed to Skopas, and, above all, Phidias’ life-size Athena Parthenos, found in the late 1950s and now on display at the Civitavecchia Museum. The head that complements the spectacular body distinguished by the plasticity of the chiaroscuro of the folds of the tunic, however, is a copy of the original, found in the late nineteenth century and transferred to the Louvre in Paris. Rare small-scale copies of the Athena from the Parthenon remain, and the one from Civitavecchia stands out for its quality of execution and state of preservation.

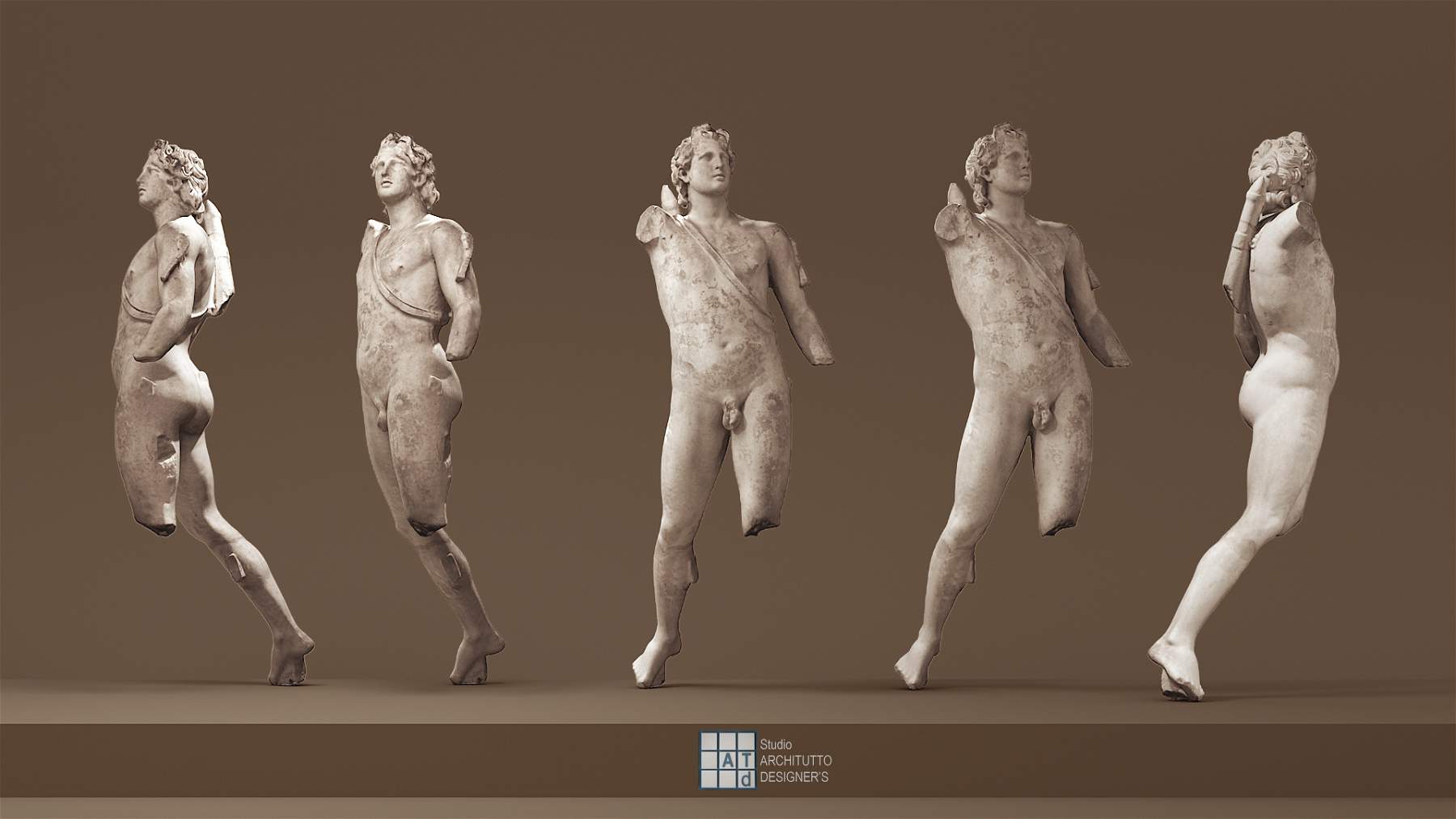

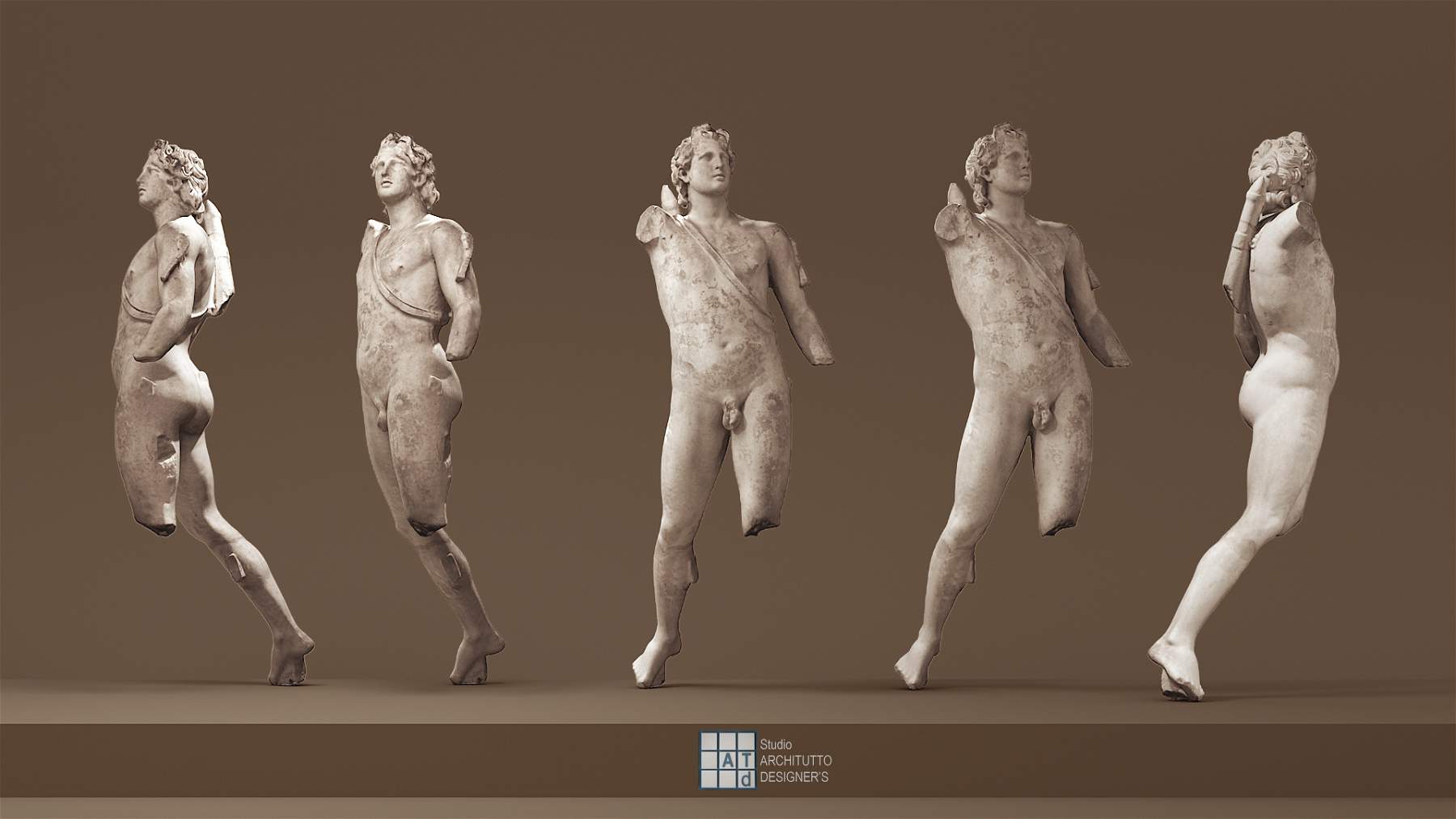

The protagonist of the Civitavecchia museum’s “rediscovery” is, as mentioned, a dynamic Apollo about 2 meters tall, which, next to the Pheidian Athena, captures the gaze of museum visitors. The statue, in the head with delicate youthful features, in the spiral movement of the torso and in the exaggerated chiastic relationship of the limbs, betrays a clear influence from the style of Lysippus, Alexander the Great’s favorite artist and one of the greatest sculptors of antiquity. The work, which can be dated to the 1st-2nd century AD like the more famous and restored Apollo Belvedere in the Vatican Museums (considered a replica of a bronze by the sculptor Leochares, to whom the Apollo of Civitavecchia had also been wrongly compared), was found in 1957 inside Villa Simonetti, also in the context of Ulpian’s great maritime villa. The statue was found mutilated, with fragments of the left leg, the right hand and the torch being held next to it, which, not reintegrated in the subsequent restoration, ended up in museum storage.

|

| The Apollo of Civitavecchia |

|

| The Apollo seen from the back |

|

| Fragment of the hand and torch. |

This admirable work has in the past been the focus of studies by the recently deceased Professor Paolo Moreno, a specialist in Greek sculpture and author of important essays on Lysippus and the Riace Bronzes. Moreno, analyzing the combination of ancient literary sources and monuments from archaeological collections, highlighted the great quality and iconographic importance of the Apollo of Civitavecchia, considered to be no less... than a replica of the Colossus of Rhodes. The grandiose bronze statue dedicated to the Sun-Helios, the island’s highest deity-was made in 293 B.C. by Carete di Lindo, a faithful pupil of Lysippus, a work of unprecedented height reaching almost 32 meters. Raised to celebrate the liberation from the siege of Rhodes by Demetrius Poliorcetes, as part of the wars fought between the heirs of Alexander the Great, ancient sources record the god holding a torch clad in gold, symbolizing Phosphor, that is, the planet Venus visible at dawn the moment it precedes the Sun. Carete’s naked colossus was felled by the disastrous earthquake that devastated Rhodes in 228 B.C.; its fragments lay on the ground for a long time, remembered by Pliny the Elder(Naturalis Historia, XXXIV, 41 ff.) for the grandeur so great that the fingers were larger than many whole statues, and for the immense cavities that opened between the shattered limbs.

In the slender and harmonious torsion of the torso to the left, the Apollo-Helios of Civitavecchia carries, leaning on his back, the quiver closed with the shoulder strap and, with his lowered left hand, holds the bow, desinent in the head of a swan. It is presumable that in the bronze original, the weapon was held sideways, so that it rested on the ground with one end and created balance to the right side of the body, which was excessively unbalanced by the foot raised at the tip and the right arm raised above the head, holding the flaming torch. Larco was also meant to be functional in hiding the iron rods recalled by the sources to secure the colossal work to the ground.

The identification of theApollo of Civitavecchia with the Colossus is further strengthened, according to Moreno, by the near identity of the young face (the upward motion of the head, the half-open mouth, the eyelids barely lowered in an effort to look up, and the details of the hair with frontal anastolé) with a terracotta head preserved in the Rhodes Museum that, presenting the holes for the attachment of the crown of rays, is unquestionably a replica of the god Helios. The Rhodian head, together with the overallimposition of the Civitavecchia Apollo with the torch raised, probably deliver us the most complete and credible image of the famous Colossus of Rhodes. The rediscovery of marble fragments in the warehouses of the Civitavecchia Museum, which were never reintegrated because the statue is missing part of the left leg and the arm that supported the torch, now displayed in the Museum alongside the work, make it possible to model theApollo-Helios three-dimensionally (the graphic reconstruction is by Massimo Legni of Architutto Designers), and to fully understand the majesty of the gesture and limponence of the sculptural set-up, in full adherence to the graphic reconstruction already hypothesized by the scholar.

|

| Reconstruction of the Apollo of Civitavecchia with the torch. |

|

| Three-dimensional graphic reproduction |

The Colossus was supposed to stand in the sanctuary dedicated to the god Helios at the foot of the acropolis of Rhodes at the road leading to the harbor, although the marked distance between the feet that remained firmly in the base of the Civitavecchia copy fueled the fanciful idea that a ship might have passed between its legs and that the Colossus was placed at the entrance to the harbor, constituting with the radiance of the flashlight a reference for sailors. The erroneous stereotype of the Colossus of Rhodes with its spread legs resting at the entrance to the dock was consolidated over time and was repeated in modern-day engravings and paintings, even becoming a modern souvenir for sale in Rhodes. The solemn gesture of the Colossus was even immortalized by the Statue of Liberty in New York, donated by France and inaugurated in 1886, a work by Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi inspired precisely by the famous Rhodes monument, based on the epigram that would have been carved at the base of the work and preserved in the Palatine Anthology (VI, 171). In fact, the Statue of Liberty shares with the Apollo-Helios of Civitavecchia, in addition to the arm raised with the torch, the emphasis of the movement of the right leg carried backward, an expedient used to increase the posing surface of a huge monument. Philóne of Byzantium, a Greek writer on technical subjects from the 3rd century B.C., who had seen Carete’s wonder in person, recalled it thus, “There is now in the world a second Sun,” which we can now see again in its original form in an Italian museum.

Massimo Osanna, director general of the Italian Museums states about the reconstruction of the Apollo: “The case of the Civitavecchia Museum, on which the Ministry is investing for a redevelopment in terms of fruition, should be a virtuous model for the lesser-known archaeological museums that dot our territory. Loaded with significant evidence for the historical and cultural context on which they insist, they are also capable of reserving real discoveries, as in the case of the astonishing affair of the Apollo, whose significant fragments had been wrongly forgotten in the dust of the deposits. Museum deposits should be made usable, considered as archives and libraries of objects, which can also facilitate the recontextualization of works of art, wherever it is possible and the conditions of protection and safety exist.”

|

| The National Museum of Civitavecchia reopens by exhibiting the... Colossus of Rhodes! |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.