When in 1998 Frank Miller (Olney, 1957), an American cartoonist and screenwriter, published 300, published by Dark Horse Comics, the American comics landscape was undergoing a phase of transformation: the superhero language was seeking new avenues, and the graphic novel was establishing itself as a form of storytelling capable of communicating with literature and cinema. In this context, the account of the Battle of Thermopylae that took place in 480 B.C. and was fought by the Spartans commanded by Leonidas I against the Persian army, establishes itself as one of the most successful trials of the author of Sin City and Batman - The Dark Knight Returns. Not because of the editorial success and impact that would inspire Zack Snyder’s film adaptation a few years later, but mainly because 300 represents a mythopoetic reflection on history, and thus on theglorious creation ofa myth. To examine, therefore, the reasons that make 300 an excellent comic book is to address at least four dimensions: graphic form, narrative structure, symbolic value, and thecultural impact the work has had on audiences over the years.

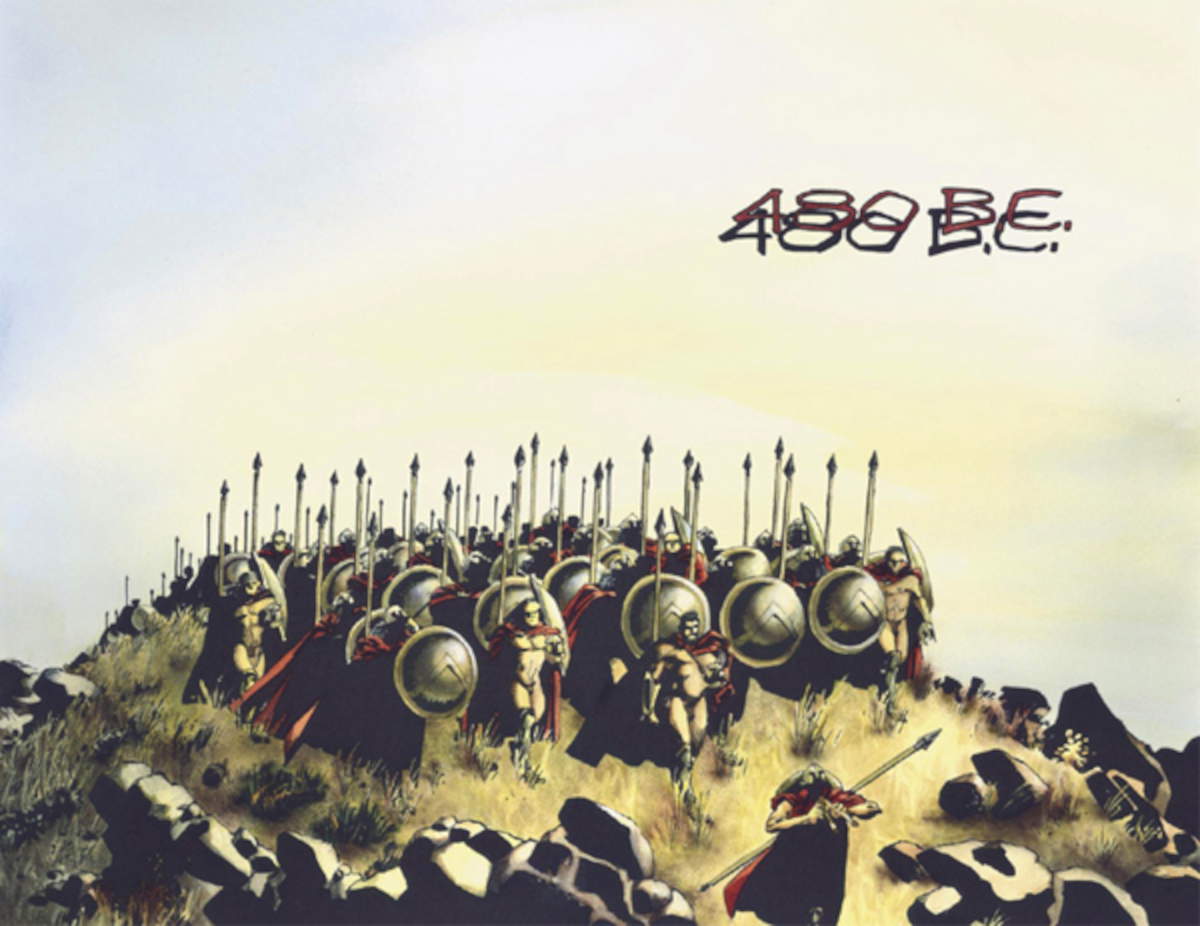

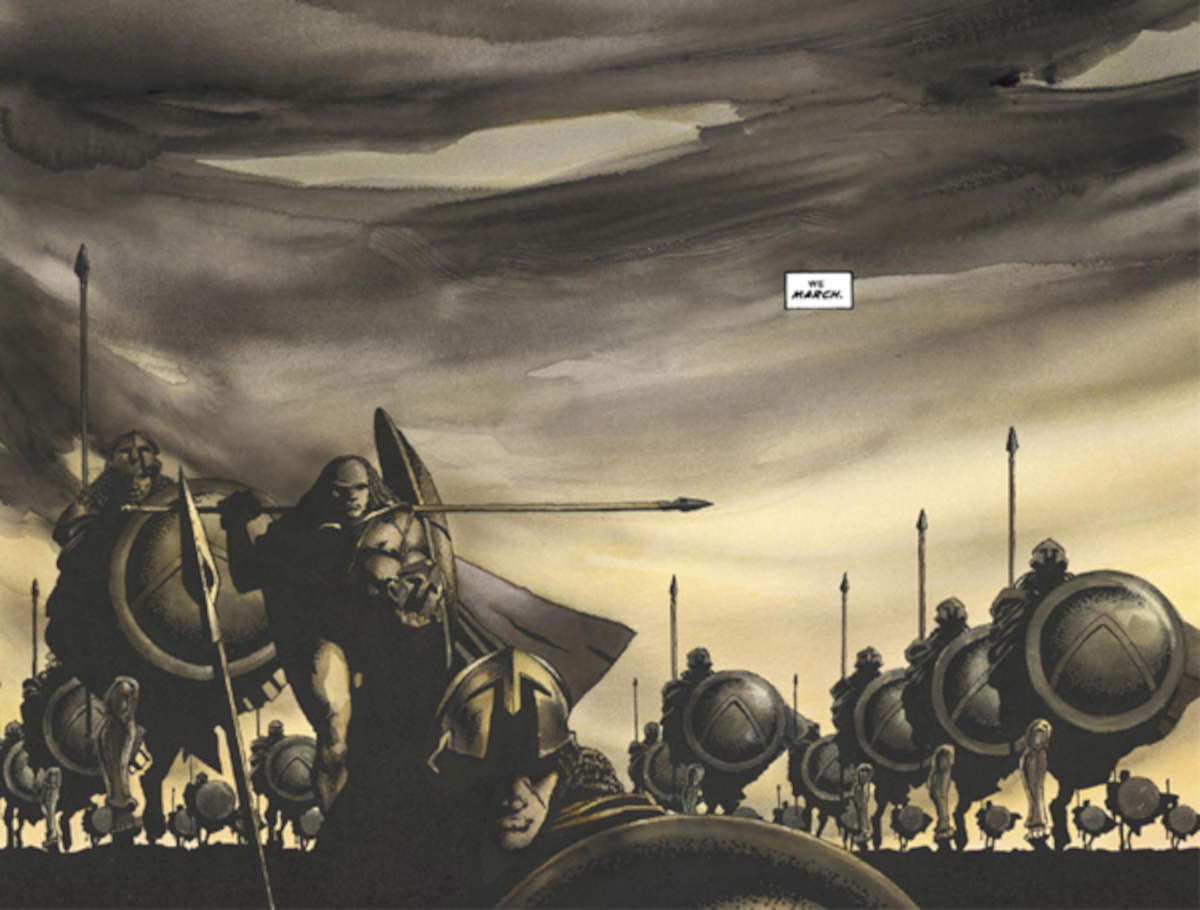

The first striking feature of 300 is the choice of format. Miller opts for a horizontal configuration, with very wide boards that recall the cinematic view of the widescreen. It is an uncommon solution that forces one to read in a different, almost contemplative way, bringing the experience of reading closer to that of viewing works of art. Miller’s pages thus become the battlefields of Leonidas; they are paintings in which figures stand out (sometimes reduced to silhouettes), other times detailed in sculpted faces and bodies. In this context, the collaboration with Lynn Varley, Miller’s longtime colorist (and wife), accentuates the aesthetic choice. Saturated, intensely contrasted colors in warm shades of ochre, red, and brown harken back to the vision of the arid earth under the sun. For Miller and Varley, there is no room for psychological nuance: the color is textural, direct. The result, then, is a comic strip that is striking in its ability to shape the page into a totalizing perspective, with a graphic composition that enhances monumentality without fearing it.

300 is not a historical account of the Battle of Thermopylae. Miller does not intend to do historiography; rather, he sets out to formulate a mythopoesis. The story of 300 belongs to legend. What does this mean? It means that in Miller’s narrative the facts are distorted, the numbers are exaggerated, and the enemies (in this case the Persians) take on monstrous proportions. It does not matter the accuracy of the historical facts, it matters the power of the tale: it matters heroism and memory, the kind told in the tales of ancient Greece. For Miller, Leonidas is not the same hero that Jacques Louis-David portrays in the 1814 painting Léonidas aux Thermopyles .

The narrative construction of the comic book, punctuated in five chapters, follows a tragic course. King Leonidas emerges as a doomed hero. He is lucid in his awareness of his fate. Indeed, the march to Thermopylae, the desperate resistance, the betrayal of Ephialtes, and finally the heroic death of the three hundred Spartans draw a path that respects the structure of tragedy: hybris (arrogance), agniation (revelation), and catastrophe. Those who read 300 know from the beginning how it will end, but what matters and remains is the idea that freedom and civilization are defended even at the cost of one’s life, for Miller is the sacrifice to be paid. In any case, one of the elements that has divided critics the most is the symbolic interpretation of the comic book. On the one hand, there are those who have seen in the work an ideological reading, too close to an exaltation of war and a militaristic society; on the other hand, there are those who recognize Miller’s ability to restore the archetypal dimension of myth. In reality, the two aspects coexist. 300 should be read as a tale that uses extremes to shape universal symbols. Sparta is the paradigm of discipline and the idea of community prevailing over the individual. The Persians, on the other hand, appear as a boundless and monstrous horde, a representation of chaos, corruption, and Oriental decadence. The juxtaposition is therefore meant to reiterate the contrast between civilization and barbarism. As written earlier, the author of 300 emphasizes excess to approach the logic of myth, not hide it.

Miller’s authorship can also be recognized in his ability to bend historical material to the needs of comics. There is no pretense of telling how it really happened. Instead, there is the ambition to revive the myth. In this sense, 300 stands in a tradition of works that go beyond entertainment comics-Miller aspires to a total artistic language. Why then is300 a good comic book? Because it has been able to speak, and still speaks, beyond the boundaries of its form. Editorial success led to the 2006 film adaptation, which, though with its own liberties, kept the original aesthetic intact. The film of 300 managed to mold Miller’s plates into nearly faithful sequences. Rarely does a film succeed in closely replicating the layout of a comic book, which shows how cinematic and grandiose Miller’s graphic concept was already in itself. At the same time, 300 stimulated discussions about the relationship between art and ideology, how aesthetic representation can convey political visions, and how myth can be reinterpreted in a contemporary key. We can love it and we can criticize it, but 300, remains a work that can still be discussed.

In 2018, Dark Horse also published Xerxes: The Fall of the House of Darius and the Rise of Alexander, written and illustrated by Miller, a work that serves as both a prequel and sequel to 300, chronicling the rise to the throne of Xerxes I and the fall of the Persian Empire under Darius III, who was defeated by Alexander the Great. Undoubtedly an extension of the universe of the first comic book that expands the boundaries of the story without altering the epic nature of the original work.From this connection comes 300 - The Dawn of an Empire, a 2014 film directed by Noam Murro. A parallel tale to Snyder’s 300 (and thus not a direct sequel), it is inspired by the comic book Xerxes. The film focuses attention on the battles of Cape Artemisius and Salamis: the former fought at the same time as Thermopylae, the latter occurring about a month later. The film also traces Xerxes’ origins, revealing his past and the reasons why he declared war on Greece.

A year after the clash at Thermopylae, in 479 B.C., the war shifted to Plataea, where Greeks and Persians faced each other in a bloody clash. Victory accrued to the Greeks, but Persian troops devastated the Acropolis of Athens(here for the article devoted to the Persian Colmata). To say, then, that Frank Miller’s comic book is a good book is to acknowledge its inherent strength as a sequential work of art. It is a book that connects an entirely new graphic concept to a mythic narrative, an impactful aesthetic to a symbolic reflection. After all, what makes 300 a good comic book is its ability to give us a sense of the epic: the idea that even in sacrifice there is a form of greatness. And it is precisely in that greatness that Frank Miller’s comic finds its strength.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.