by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 24/02/2019

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Panorama. Landings and Drifts of Landscape in Italy," in Bologna, Fondazione del Monte di Bologna e Ravenna, from January 29 to April 13, 2019.

Landscape, Henri-Frédéric Amiel was convinced, reveals a state of our soul. The French philosopher entrusted this thought to his Journal intime drafted between 1883 and 1884: the experience of Friedrich with his panoramas at the window had been closed for a few decades (but in a certain way still alive), the invention of the camera had been fully accepted (or at least so by the most open-minded, modern and far-sighted painters), and by now taken the road that would lead many to abandon an art based on pure mímesis, landscape painting was also ready for a further revolution. Friedrich, observing his Dresden from behind his studio window, had introduced into landscape painting the subject that observed it (and it was a poignant vision, an unattainable desire, a romantic yearning for infinity that could find no satisfaction), theImpressionists would be the first to study the changing conditions of light on the landscape, and certain Symbolist painting first (Khnopff above all) and then Divisionist painting (think of Segantini, Grubicy, De Maria, and to some extent even Morbelli) would have charged the landscape with an unprecedented spiritual tension in order to use it as a means of transmitting a certain state of mind to the observer. And shortly thereafter landscape painting would undergo further upheavals: proof of this are the futurist views that tell us of cities in profound transformation, projected towards modernity.

We have here briefly provided a very rapid, and necessarily incomplete, overview of the events that would lead to the landscape of the twentieth century, above all to premise that Claudio Musso is right when, in introducing his exhibition Panorama. Landings and Drifts of Landscape in Italy (at the Fondazione del Monte in Bologna until April 13, 2019), specifies that it is difficult, if not almost impossible, to find a definition of “landscape.” wanting to mention some illustrious examples, for Fernow landscape is like music, since it has no precise content and acts on the feeling of the observer just as music acts on the listener, and still according to Ragghianti landscape is not an object of perception, but rather “a scenery or a spectacle like any film or any play or any ballet” (and consequently contemplating a landscape, for a painter, would be equivalent to “making shapes, colors dance,” as the ballet master would do with dancers), and Argan, discussing the works of Juvarra, had coined the expression “architectural nature” to refer to landscape. From the difficulty of finding an unambiguous way to landscape thus arises the need to rely, indeed, echoing Rosenberg, on a s-definition to remark that, Musso writes, “it is the landscape itself that defines itself, that continually updates its identity, both on a literal level (circumscribing, de-limiting, de-terminating a con- end), and on a cultural level, dependent as it is on the epoch and latitude in which the observation takes place.” Thus, there is no single landscape (and therefore no single landscape painting): there are probably as many landscapes as there are subjects of vision.

However, it is possible to bring out a common thread that binds the experiences of the artists that Claudio Musso has gathered for his group show that, in a certain way, intends to photograph the status of Italian landscape art today: in a way that is admittedly incomplete, but nonetheless effective. It is a thread that stems from an exhibition also held in Bologna, almost forty years ago: between 1981 and 1982 the local Galleria d’Arte Moderna hosted an exhibition, curated by Tomás Maldonado (Buenos Aires, 1922 - Milan, 2018), which was entitled Landscape: image and reality. Right from the title, it appeared clear how the aim was to present the public with the experience of landscape on two levels (on the one hand, the object of vision, on the other, the subject), which in the artist’s experience are co-present, detached and then reunited, mixed, divided and chased, moving on different dimensions (the lived, the imagined, the dreamed, the remembered, the constructed, the hypothesized, and so on): the current exhibition starts from similar assumptions, with a leap forward a few decades. And of the 1980s exhibition it preserves theopen-mindedness, the “exploratory” attitude (as per Tomás Maldonado’s definition), the intention not to provide answers but to prepare a research ground.

|

| Exhibition hall Panorama. Landings and drifts of landscape in Italy.

|

|

| Hall of the exhibition Panorama. Landings and drifts of landscape in Italy.

|

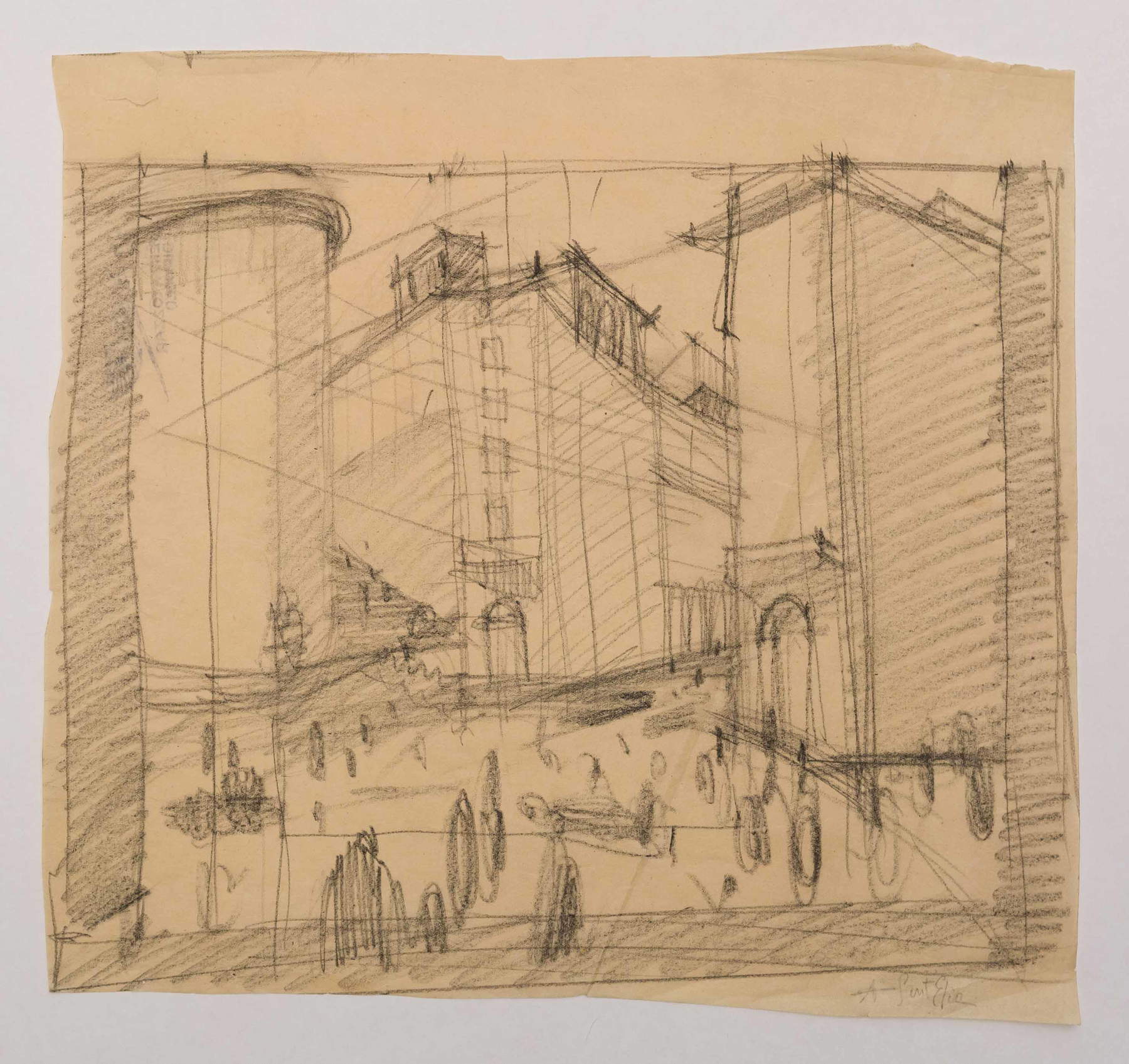

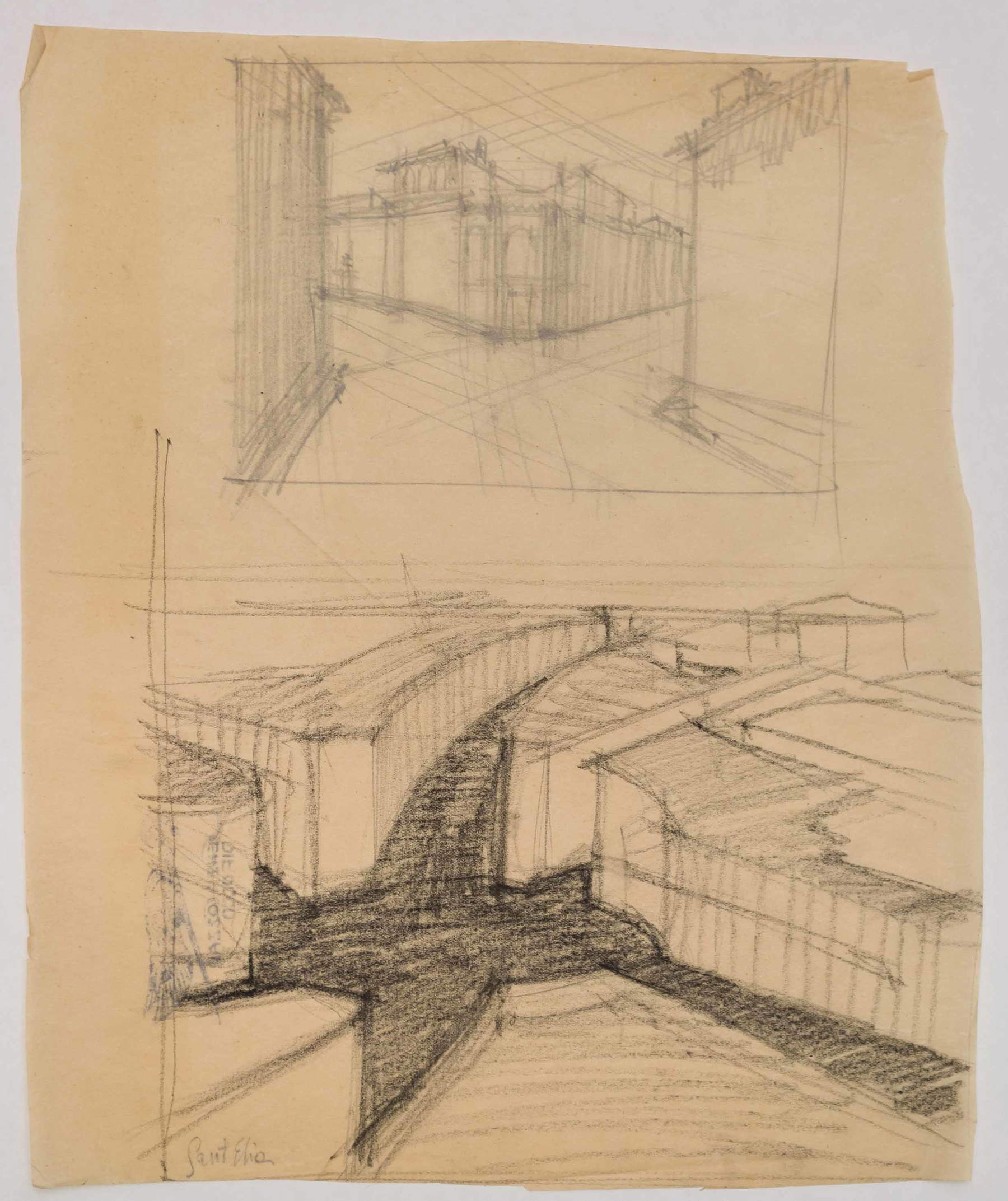

The photographs of Luigi Ghirri (Scandiano, 1943 - Reggio Emilia, 1992), one of which, Passignano, placed at the opening of Panorama as a clear manifesto of intent, were also discussed in Landscape: image and reality: in tracing a brief outline of his poetics, Vittorio Savi wrote that Ghirri’s images were composed to perfection already within the photographer’s viewfinder (because for Ghirri the landscape, even before being such, is an image of the landscape), and the artist himself, in describing the Italian Landscape series of which Passignano is a part, explained that it was not so much a matter of description as of a perception of the place that is the subject of the photograph. And of the place, Savi pointed out, Ghirri did not possess the scientific notion, but rather “the qualitative reality and the awareness that it is a concept clearly distinct from the categories of landscape (the set of physical facts that manifest themselves and coexist in a transitory form in the space of a territory, subjectively perceived by the observer) and site (the circumscribed territorial sphere of which all the characteristics are known).” This premise of “landscape as image” in the exhibition is then enriched by the drawings of Antonio Sant’Elia (Como, 1888 - Monfalcone, 1916), which arrive on loan from the Cirulli Foundation of San Lazzaro di Savena: if Ghirri’s photographs constitute the conceptual start of the exhibition, Sant’Elia’s drawings represent a sort of historical introibo, and if the landscape of the 21st century is largely urban views (obviously in all its possible declinations), the futurist architect par excellence, with his drawings that imagine futuristic cities of tomorrow, is its most natural anticipator.

And if the city is the starting point, one cannot help but look at the opposite wall to immerse oneself in the industrial ruins of Andrea Chiesi (Modena, 1966), which in part force us to come to terms with a reality made up of precariousness and destruction, but at the same time are animated by an unexpected spiritual tension that begins with a sense of melancholy, to be understood as “a signpost of an erased geography,” according to Ghirri’s own definition. This sense of bewilderment involves the search for a renewed relationship with nature (and nature, moreover, is the protagonist of Chiesi’s most recent research, although it should be emphasized that he has never abandoned his art), or a return to intimate situations: in the exhibition we have a way of approaching the Emilian atmospheres of The House, another series by Andrea Chiesi of which a painting is exhibited in Bologna, but also with the Stellar Road by Davide Tranchina (Bologna, 1972), which recounts a familiar landscape, that of the Via Emilia, in order to re-discuss it by making it transmigrate into a universal dimension. The suspended atmospheres of Chiesi’s and Tranchina’s works continue with Francesco Pedrini ’s (Bergamo, 1973) Tornado, a drawing with which the artist tries to communicate the idea of the inability to grasp in their completeness certain phenomena of nature that everyone, however, has well in mind (and which Pedrini, moreover, with his Strumento che raccolgono i suoni e i rumori del cielo, invites us to listen to), and with Valentina D’Amaro ’s (Massa, 1966) Olî, present in the exhibition with a couple of works from the Viridis series : nature, seemingly so close to one’s felt self, is actually elaborated, synthesized, stripped away, so that the landscape loses its own character and becomes a metaphor for touching deep chords, leaving a sense of expectation to take over (it almost seems as if Valentina D’Amaro’s estranging views must transform at any moment: green, after all, is also a symbol of life, of regeneration). The first room closes with Daniel González (Buenos Aires, 1963) and his Low-Cost Panorama (an ephemeral architecture, that of an inflatable soccer field enclosed in a package, which offers the possibility of temporarily changing the space), and with the ironic works of Filippo Minelli (Brescia, 1983) who, like the Argentine artist, investigates the theme of perception of space, trying to disorient the observer even if with a somewhat trite expedient, that of superimposing images (in this case downloaded from the Internet) on the real piece of landscape to which they correspond.

|

| Luigi Ghirri, Passignano, from the series Italian Landscape (1988; cibachrome from slide, 19.9 x 24.9 cm). Courtesy private collection, Bologna

|

|

| Antonio Sant’Elia, Untitled (ca. 1912; pencil on paper, 29.6 x 31 cm). Courtesy Fondazione Massimo and Sonia Cirulli, Bologna

|

|

| Antonio Sant’Elia, Untitled (ca. 1912; pencil on paper, 29.7 x 24.5 cm; Bologna, Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli)

|

|

| Andrea Chiesi, Eschatos 2 (2017; oil on linen, 50 x 50 cm). Courtesy d406, Modena

|

|

| Andrea Chiesi, The House 28 (2004; oil on linen, 100 x 140 cm). Courtesy Angelo Zanetti, Modena

|

|

| Davide Tranchina, Strada Stellare #3 (2016; true giclée print, dibond, frame, 45 x 45 cm). Courtesy the artist

|

|

| Davide Tranchina, Strada Stellare #4 (2016; true giclee print, dibond, frame, 45 x 45 cm). Courtesy the artist

|

|

| Francesco Pedrini, Tornado#6 (2016; graphite, charcoal, pigments on Kozo paper, 100 x 140 cm). Courtesy the artist and Galleria Milano, Milan

|

|

| Francesco Pedrini, Strumento#5 (2017; wood, copper and leather, height 175 cm, diameter 15 cm). Courtesy the artist and Galleria Milano, Milan

|

|

| Valentina D’Amaro, Untitled, from the Viridis series (2016; oil on canvas, 40 x 50 cm). Courtesy private collection

|

|

| Daniel González, Low-cost Panorama (2018-19; ephemeral architecture, inflatable soccer field and packaging). Courtesy the artist

|

|

| Filippo Minelli, Untitled (2018; mixed media). Courtesy UNA, Piacenza

|

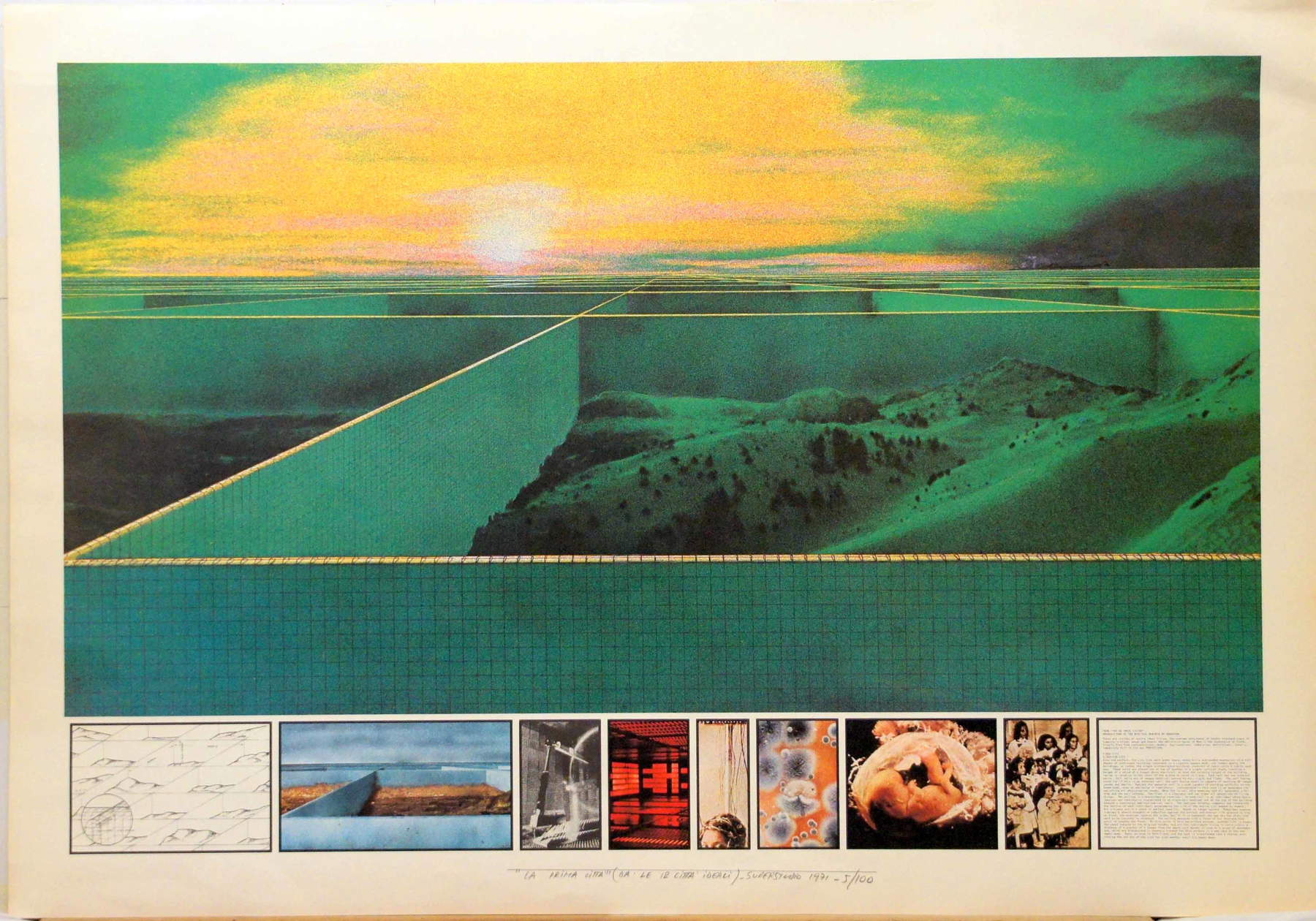

Wanting to find a link that unites the works in the second room, one could think of landscape as encounter and clash (for example, between nature and the city: a city moreover also evoked with the live landscape of the glass door facing Via del Monte), as stratification, as a measure of sustainability. It starts with the extreme consequences represented by the dystopian visions of the Superstudio group, the architectural firm founded in 1966 in Florence by Adolfo Natalini, Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, Gianpiero Frassinelli, Roberto and Alessandro Magris, and Alessandro Poli: the exhibition presents a couple of works, including the first of the Twelve Ideal Cities, an extreme consequence of modernity and the control exercised over the masses. A natural landscape appears caged in a grid that is lost beyond the horizon: it is the ideal city where each cell corresponds to a unit that guarantees its inhabitants everything they need to achieve a perfect and eternal life (but which does not tolerate dissent: those who rebel against life in the ideal city are crushed by the ceiling of the cell, which lowers to the floor). With their panels, each accompanied by a description drafted in an almost narrative form, Superstudio present the viewer, writes Claudio Musso, with “an alteration that reaches from the design of the territory to social dynamics.” Almost all the artists in the room speak of alterations, starting with Margherita Moscardini (Donoratico, 1981), who instead situates her sophisticated dystopia in history, exhuming its remains (as in Maquette A, a set composed of asphalt, a marble relic, dust and glass) as if to say that for the landscape, once it has undergone a modification, there is no possibility of returning to its origins. So much so that the landscape itself is indelibly marked, as happens in The Mountains’ Factory, a video that the Tuscan artist presents for the first time precisely at the Bologna exhibition.

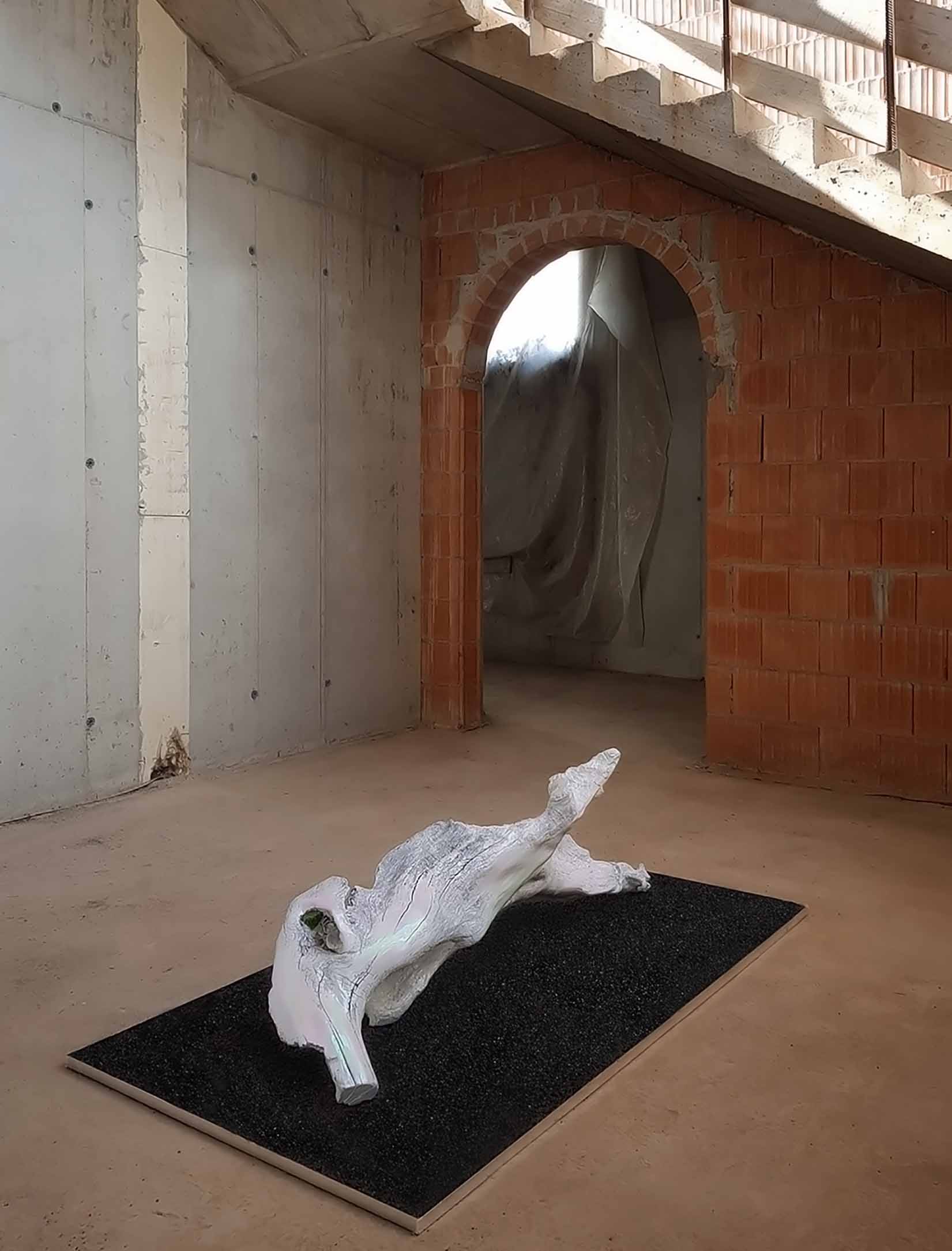

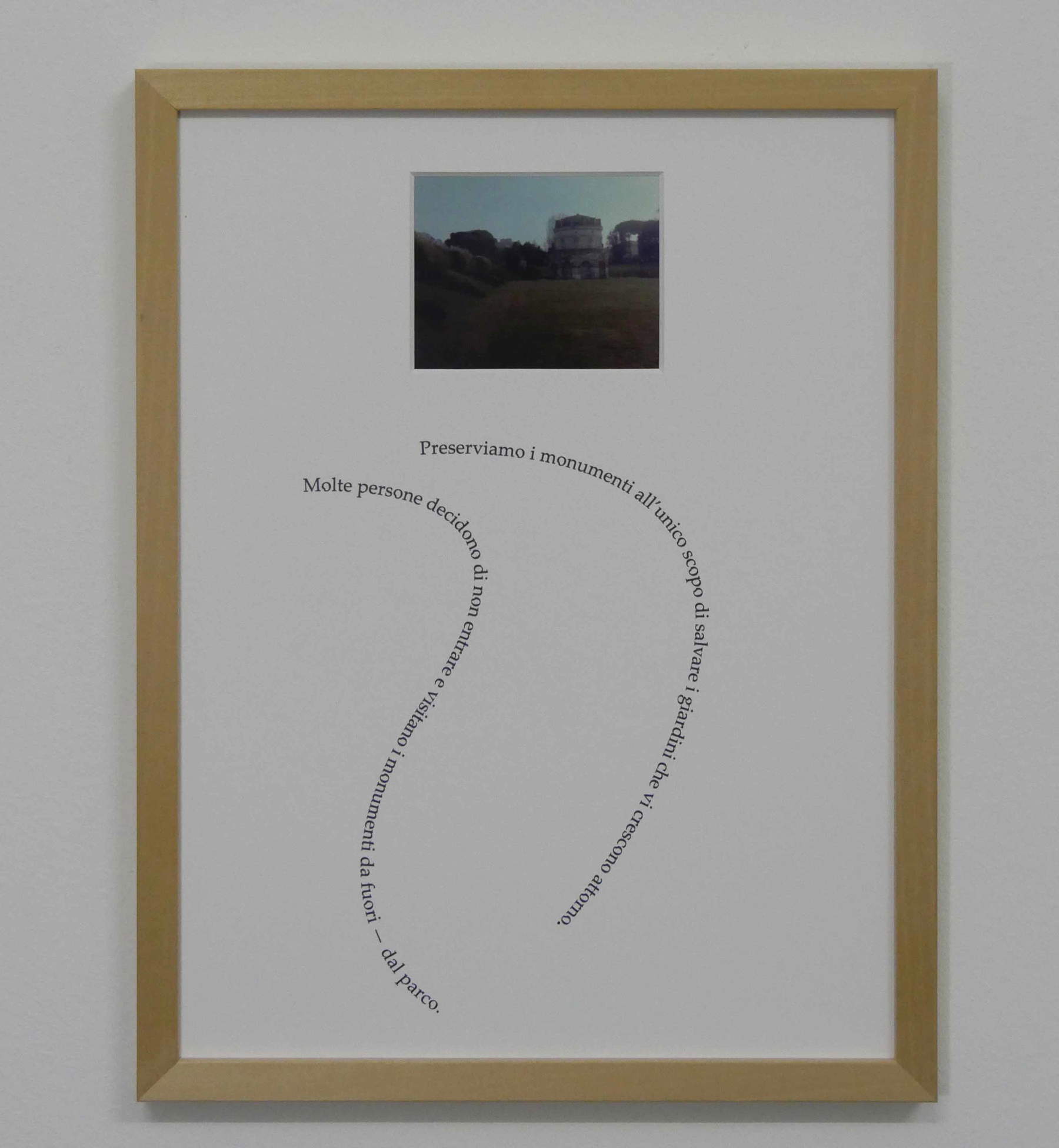

The clash (or encounter) between nature and the city is as vivid as ever in the work of Andrea De Stefani (Arzignano, 1982), who collects trunks from the beach as objet trouvé and then gives them new meanings by covering them with coachwork paint and placing them on a bed of asphalt: the result is a bizarre effect of estrangement that to some extent brings to mind great Baroque sculpture. Also aiming to reflect on themes of landscape transformations and the relationship between man and nature is the work of Andreco (Rome, 1978), an artist and PhD in environmental engineering whose experiments are largely aimed at investigating the consequences of the interaction between landscape and urban space. Parade for the landscape, a well-known performance held in June 2014 in Santa Maria di Leuca (i.e., in the easternmost strip of land in Italy, the Finis Terrae of the peninsula) saw a group of figurants, citizens of local communities, move masked along a three-kilometer route along the coast carrying flags with symbols clearly referring to the landscape. Natural borders to reflect on human boundaries and limits (including political ones), flags with schematic representations of natural elements that, writes semiologist Massimo Leone in his catalog essay, evoke “the impact that the evolution and imposition of technique, in this case that of digital representation, exerts on the perception of the familiarity of the landscape.” Closing the room are the works of Riccardo Benassi (Cremona, 1982), who engages in a direct dialogue with Superstudio, and not only because his Vertical Highway was conceived in collaboration with them, but also because the poems in Così per dire attempt a sociological analysis of the landscape translated into verse (or something similar) that runs on sheets next to images of man-made landscape.

|

| Superstudio, The First City, from The Twelve Ideal Cities (1971; lithograph, 100 x 70 cm). Courtesy Superstudio Archive

|

|

| Margherita Moscardini, Maquette (2013; asphalt, marble find, marble dust, glass, environmental dimensions). Courtesy Collezione Anna and Francesco Tampieri, Modena - Collection of Collections CoC

|

|

| Andrea De Stefani, Smash-Up (Rino’s flowerbed) (2017; painted wood, glass, asphalt, steel, 220 x 130 x 65 cm). Courtesy the artist

|

|

| Riccardo Benassi , Vertical Highway, Study for Scale, Scale 1:2 (2009; Hp laserprint on Hp 180 gm matt photo paper, oak frame, 50 x 70 cm). Courtesy the artist and Marco Ghigi Collection, Bologna

|

|

| Riccardo Benassi, Così per dire (park) (2016; print on Metal Kodak photo paper, laserprint on passe-partout, oak frame, 32.7 x 42.5 cm). Courtesy the artist

|

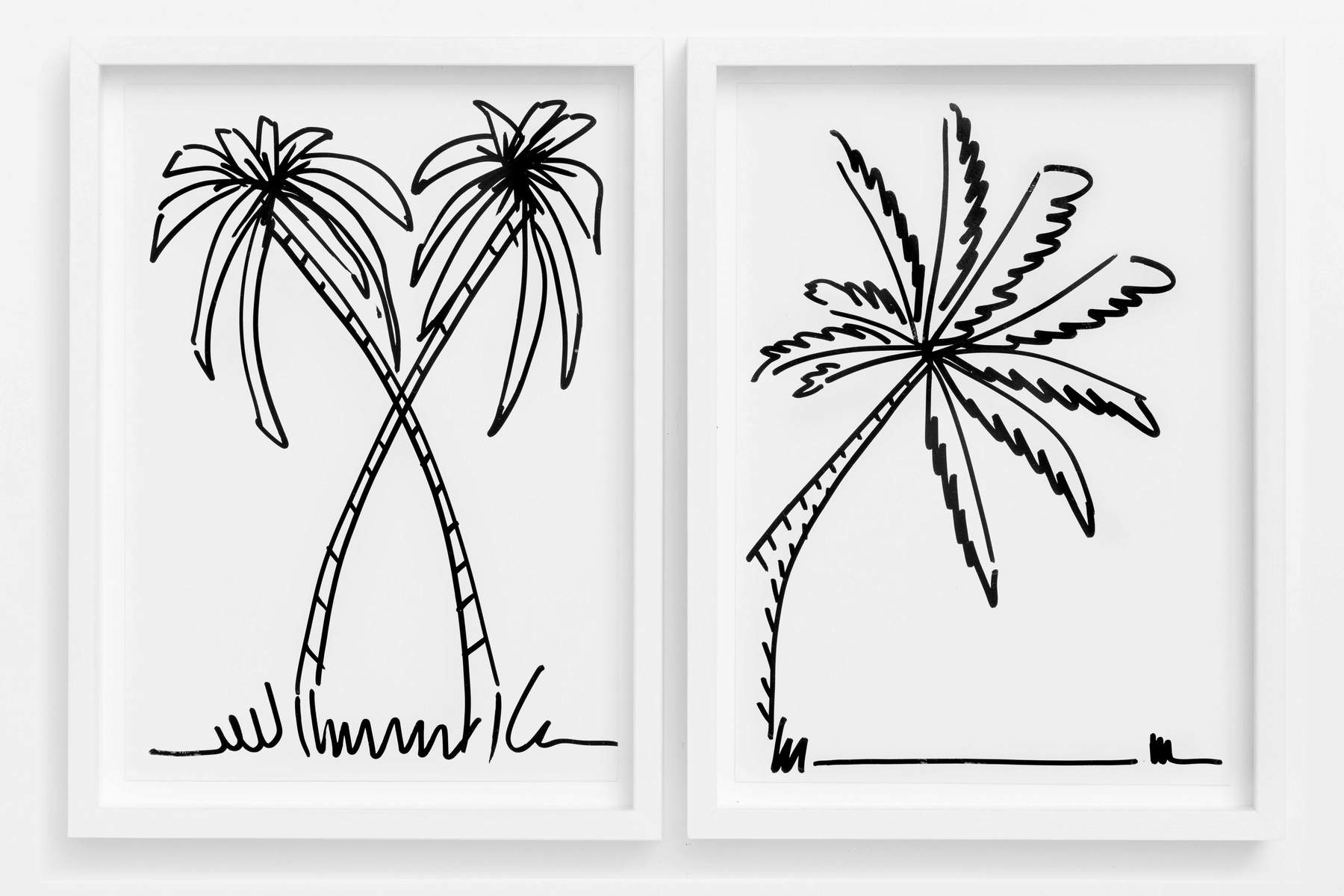

For the third and last room, the leitmotif might be the longed-for landscape, the dream landscape, and the opening is entrusted to a journey, that of Pianura uno pianura due by Mario Schifano (Homs, 1934 - Rome, 1998): a theory of acid colors and in motion appears behind a silhouette that suggests the idea of a window, as if Schifano wants to put a moving car or train inside it and intends to make us admire the view that flows before our eyes. Landscape as a journey (more expected and sought than actually accomplished) is also the theme of Imaginary vac ations by Luca Coclite (Gagliano del Capo, 1981), where the “imaginary vacations” are those that baby boomers were forced to spend in summer camps, now almost entirely extinct (Coclite’s work is an installation, the letters that make up the words Imaginary Holidays, placed in front of the former Colonia Scarciglia in Castrignano del Capo, Salento: admittedly, nothing particularly original, but evocative nonetheless), as well as the interesting project 32 days at Rupert, the work of Marco Strappato (Porto San Giorgio, 1982), who in 2017 spent time in Vilnius, Lithuania, dreaming of exotic landscapes. The result is thirty-two marker drawings on cardboard, with an almost cartoonish stroke, which with certain poignancy mutate the cold Baltic forests into exotic palm trees and beaches to recall, at least in the artist’s intentions, the topos of theevasion of reality typical of contemporary Anglo-Saxon youth subcultures (the palm tree, moreover, is one of the symbols of vaporwave). The circle is closed by the eighteen coconuts made together with Giovanni Oberti (Bergamo, 1982) and on display placed just below 32 days at Rupert.

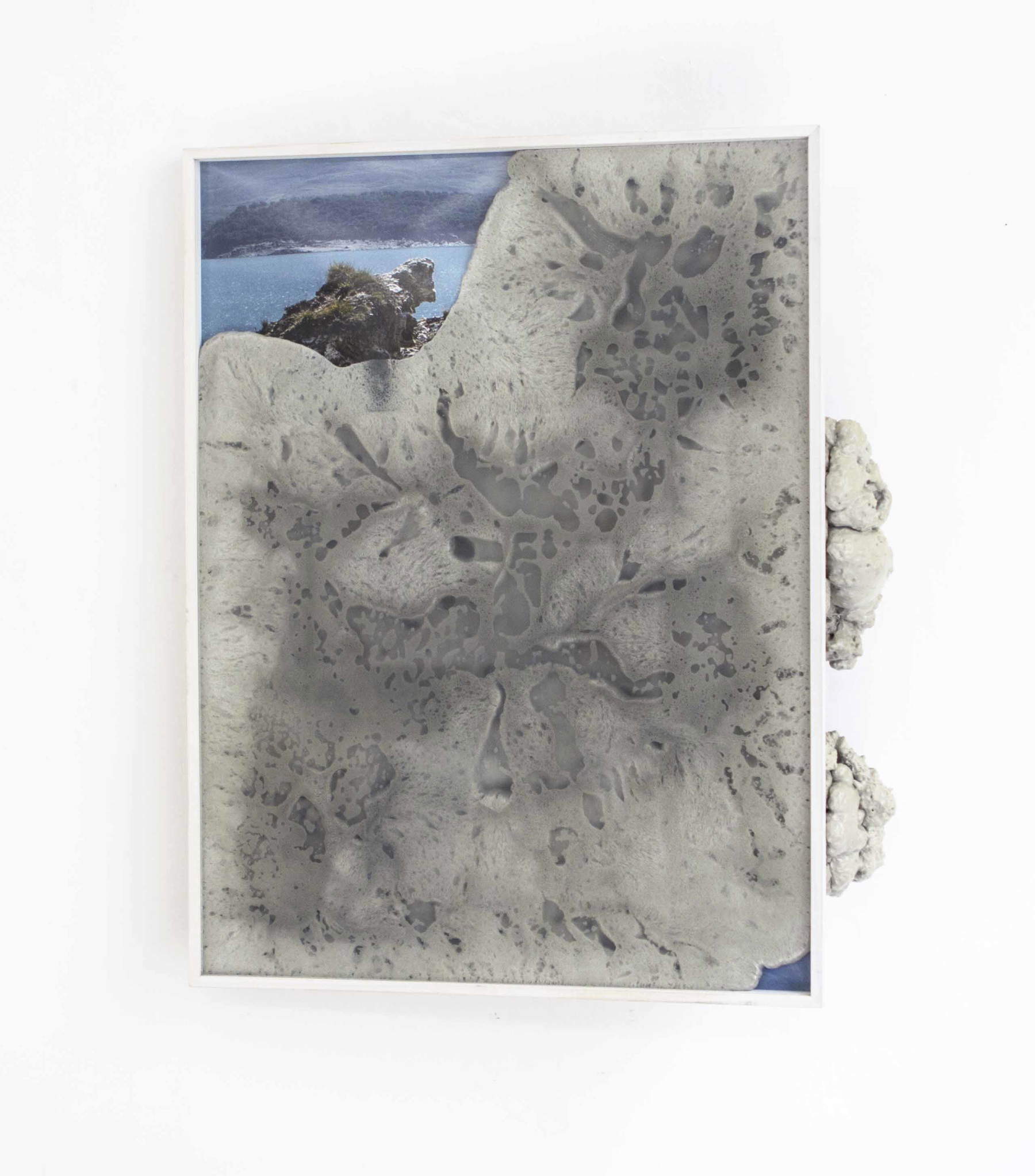

The works of Mauro Ceolin (Milan, 1963) leverage the imagination to transport us into videogame atmospheres with video game landscapes that are reproduced in watercolor or acrylic paint en plein air, as if the computer screen were to us what the window was to the Romantics, and as if Ceolin’s panoramas give life to a kind of digital Sehnsucht. Next to them are the landscapes of Laura Pugno (Rome, 1970), who spreads polyurethane over postcard photographs in order to prevent us from seeing them (and perhaps lead us to desire that landscape even more?), while in the center of the room stand the works of David Casini (Montevarchi, 1973), who paints landscapes over unusual supports (such as the protective films of smartphones) to make them become the protagonists of a story that also involves the objects of which his works are composed, which are halfway between painting, sculpture and installation. The exhibition can be made to end with the minimalist sculptures of Martino Genchi (Milan, 1982), who in Mindset places a plaster element above an aluminum plane that simulates a horizon, and a wooden wedge below: “two layers of matter as emanations of celestial and terrestrial” (so Claudio Musso), which create a new image of a landscape with two of its most basic elements, the sky and the earth.

|

| Mario Schifano, Pianura uno Pianura due (1971; enamel on canvas, 140 x 240 cm). Courtesy Galleria de’ Foscherari, Bologna

|

|

| Luca Coclite, Imaginary Holidays (2018; plexiglass, 257 x 14 cm). Courtesy the artist

|

|

| Marco Strappato, 32 days at Rupert, Vilnius. Looking into the wood, dreaming palm trees (2017/2018; 32 framed drawings, acrylic marker on cardboard, 210 x 140 cm approx.). Courtesy the artist and The Gallery Apart, Rome

|

|

| Giovanni Oberti and Marco Strappato, Three Half Dozen (2018; coconuts, graphite, powder, environmental dimensions). Private collection, Courtesy the artists

|

|

| Mauro Ceolin, DeerHuntLandscapes (2005/2006; acrylic on plexiglass, 45 x 37 x 3 cm, 12 plates). Courtesy Private Collection, Monza

|

|

| Laura Pugno, Dominant Recessive 01 (2017; photographic print and polyurethane, 61 x 46 x 16 cm). Courtesy the artist

|

|

| David Casini, Free Space (2018; glass, inlaid wood, brass, resin, tempered glass, UV digital print, 45 x 26 x 26 cm). Courtesy CAR drde Gallery, Bologna

|

|

| Martino Genchi, Mindset (2018; aluminum, steel, plaster, acrylic, oak wood, 13.5 x 27 x 12 cm). Courtesy the artist

|

One of the most significant aspects of Panorama. Landings and Drifts of Landscape in Italy (which, as it turns out, removed the names of historicized artists presents exclusively works by artists born between the 1960s and the 1980s: this is a precise curatorial choice, since the focus has been on names that are part of the first generation born in the era of massified societies and who therefore found themselves immediately immersed in their media and languages, up to those who grew up and trained at the dawn of the Internet era, all also with the aim of bringing out the different conceptions of landscape) is the ability to broaden the spectrum of the investigation to include reflections that have to do with politics, society, and at the same time with the drives of the individual. The expression “architectural nature” that Argan used to emphasize a certain characteristic of Juvarra’s art was then quoted in the opening, and it is interesting to point out that the nature-architecture pair is one of the pillars on which the Bolognese exhibition is founded and in turn opens important parentheses on the most current debates on urban development, landscape planning, the relationship between inhabitants and territory, and the use and function of public space.

It can undoubtedly be said that Panorama. Landings and Drifts of the Landscape in Italy is a courageous exhibition, and not only because, to date, the mere act of setting up a contemporary art group show is in itself a daring and arduous operation, but also for several other reasons: because of the desire to measure oneself against an exhibition that has marked the history of contemporary landscape painting in Italy (managing to recall and continue its research), because of the political nature (in the highest and noblest sense of the term) that in part animates it, because of having tried to place within an unobvious historical perspective the works of the selected contemporary painters, sculptors, photographers and performers, and because of having attempted (and achieved) a balanced balance of the languages used by the artists in the exhibition. Lastly, a mention of the catalog, which, although much more agile than the one in the 1980s exhibition, has the merit of also providing the reader with images of works not in the exhibition to provide a broader perspective on the selected artists (although perhaps greater clarity in presenting which works are in the exhibition and which are not would have been desirable, but this is perhaps due to the fact that the volume is not intended to be just a catalog but more generally a publication on landscape painting in Italy today) and a rich annotated bibliography.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.