Some films become cult films because they come out at the right time, first intercepting certain epochal and existential ferments still latent with an original style destined to set the standard. One of these is Amores Perros (153 minutes), the debut film of Oscar-winning director Alejandro González Iñárritu (Mexico City, 1963), which sparked unprecedented interest in Mexican cinema among international audiences in 2000. The feature film (whose initial project was a documentary divided into episodes) fiercely investigates the social contradictions of the Mexican capital through the interweaving of three gory stories whose protagonists, belonging to different social classes, intersect their lives in a tragic car accident. In a chaotic and violent society, no one seems to be immune to the fate of overwhelm that awaits them, and everyone tries to survive at the expense of others. From the alleys of the slums where those who subsist on expedients struggle daily to the luxury mansions in which those who have managed to earn a wealthy status move, the film stands out as an exorbitant portrait of a megalopolis seen from within its bowels, whose inhabitants are sucked into a vortex of irrepressible drives and finally death, the fatal social leveler. The writing of the screenplay, co-written by the director himself with writer Guillermo Arriaga Jordán (Mexico City, 1958), lasted three years: thirty-six versions were written before arriving at the final formulation, and the selection of the fifty-two actors, many of them first-time performers, was also a long process. Guiding the casting was the search for congenital similarities between the performers and the characters, followed by training to have them live for some time in their own conditions to facilitate identification. In addition to thematically, Amores perros is also a complex film from a structural point of view: a clockwork montage makes the narrative proceed in fragments, skilfully playing with temporal lapses, flashbacks, anticipations and continuous cross-references, placing itself among the pioneers of that systematic interruption of narrative linearity that still constitutes the distinctive feature of many films, as the last Biennale Cinema also showed.

For the twenty-fifth anniversary of his legendary film, which opened the doors of the New York film industry to him, Iñárritu wanted to revive that still-alive and magmatic material by seizing the occasion of the discovery of more than three hundred kilometers of discarded film abandoned on the studio floor during the original editing. For a quarter of a century those sixteen million frames had been buried in the film archives of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), and the filmmaker, upon learning of them, decided to compose them into an exhibition-installation entitled Sueño Perro: Instalación Celuloide, revealed for the first time at the Fondazione Prada in Milan, where it will be on view until February 26, 2026 and will then transit to other international institutions, including LagoAlgo in Mexico City and The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 2026.

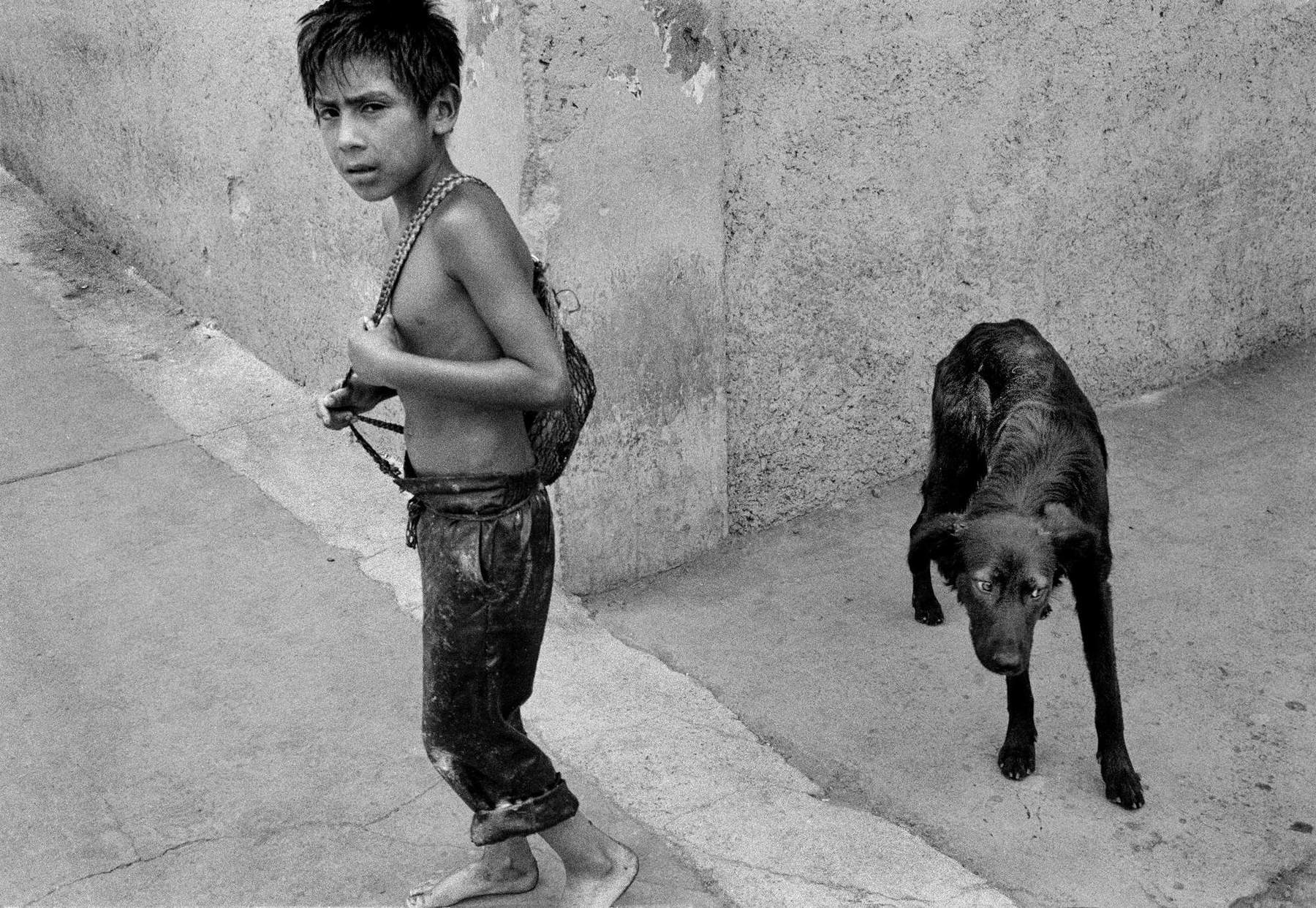

The exhibition itinerary on the ground floor of the Podium is articulated through a sequence of dark rooms, in each of which imposing 35mm analog projectors (equipment that is now as rare as the operators able to use it) broadcast a continuous stream of fragments of Amores Perros, assembled for the first time with a sound made of environmental recordings interspersed with disjointed musical sounds. In this encompassing environment, it feels like being in the belly of the whale, but almost immediately one loses track of the level of reality (or fiction) one is in and no longer knows whether one is in the celluloid underbelly of the film, in the most murkiness of Mexico City in the early 2000s or even in the heart of cinematic illusion tout court, where the intersection between those scraps of life and the raw material of the film materializes a vivid dream. The succession of intensity-laden filmic sequences, untethered from the narrative consequentiality of the plot in a web of mirroring and repetition, panders to and in some ways examines the structural building block of Amores Perros, namely the co-presence of stories that brush against each other at the whims of a merciless fate. Again, acting as a common thread between the different stories and social classes represented is the presence of dogs: in the film’s title, the word that in Spanish designates these animals is used as an adjective in a sense that roughly could be translated as “bad loves,” in reference to the violence (physical or psychological) that is felt in each scene. At the same time, dogs, whose stray population at the time of the film’s making amounted to three million, many of them employed in illegal fights, were in Aztec culture tasked with spiritually accompanying men into the afterlife. But in the bloody Mexico City evoked, resembling a circle of hell where the daily challenge is to return home unharmed, they seem to be creatures sent, rather than to guard the entrance to the realm of the dead like the mythological Cerberus, to ensure that its gates open wide for all indiscriminately.

Despite the absence of dialogue and synopsis, the installation is effective in rendering the apocalyptic vision of a metropolis teeming with life and shot through with extreme contradictions that is the film’s primary source of inspiration. Indeed, the fact that of the stories in the installation only the atmospheres and themes can be intuitively reconstructed emphasizes how in itself such a pronounced social disparity is capable of simultaneously generating multiple actions endowed with inherent cinematic potential, into some of which the director sinks his camera with stark realism. His could be described as a ruthless coring that investigates the pulsating essence of life by plumbing its most radical manifestations and subtracting them for a moment from the chaotic rush of events to observe them through the magnifying glass of each character’s neuroses. How many films exist within a film and what different possibilities of language can arise from the same footage? These are the questions from which the director started before trying his hand at the installation reworking of archival material twenty-five years after the release of a film that in many ways defined the imagery of an era.

The installation, carried out with an imperial deployment of forces like all the exhibitions at the Fondazione Prada, is effective in explicating the analytical intent underlying this process of rethinking and fully satisfies, especially thanks to the scenographic presence of the projectors and their light beams, the “immersive” character of the setting, among the most sought-after qualities in contemporary art exhibitions today. In this version, even more than in the film, Mexico City appears not as a backdrop for the stage action but as a real character, observed with horror but also with a deep love for its archaic freedom, the fragility of its balances and the tragic destructive vocation that fuels its creative power. The film’s sequences can be likened to a succession of digital murals, which in their translation into a medium as impermanent by nature as the moving image retain all the aspiration of their historical predecessors to embody a great popular and choral epic.

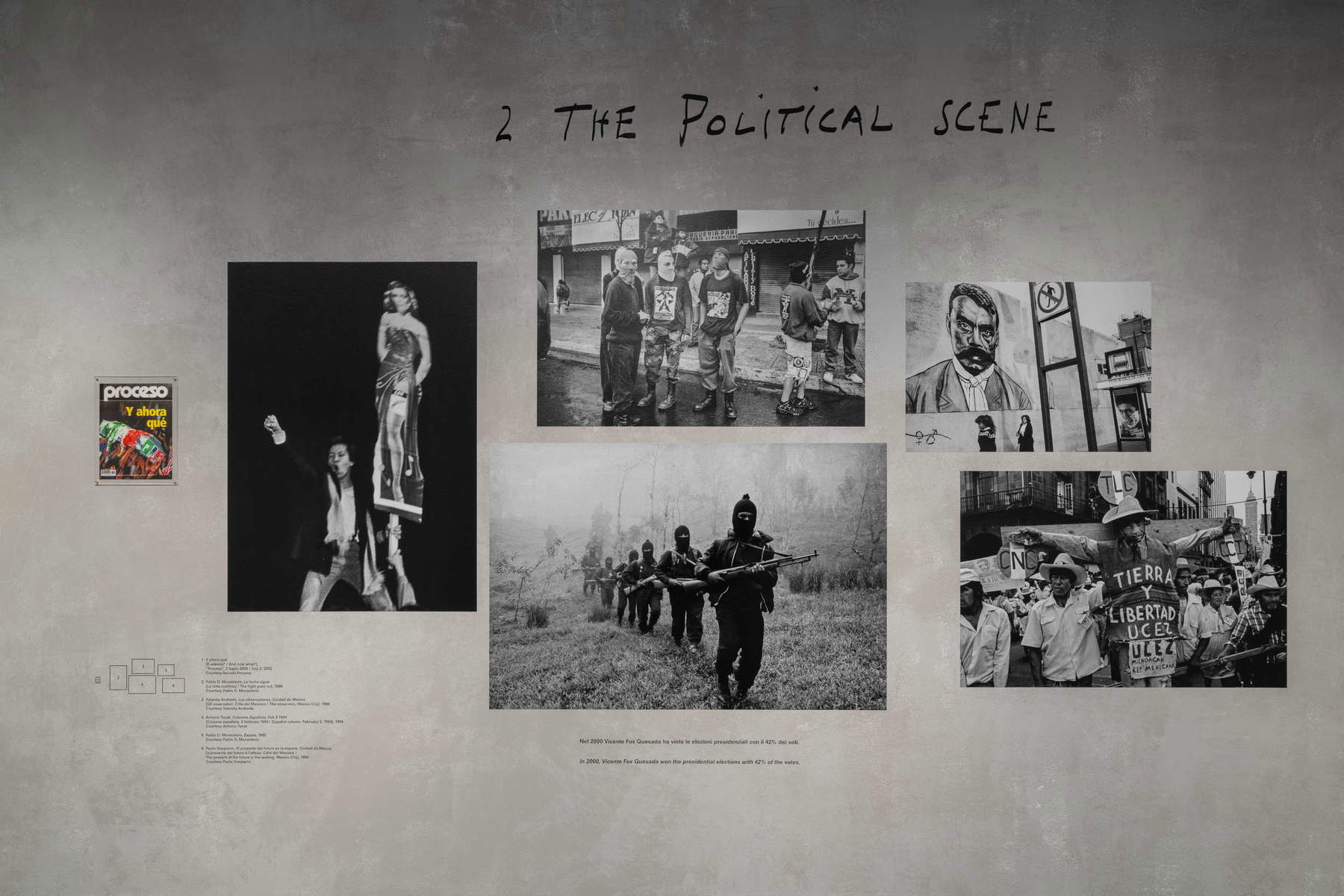

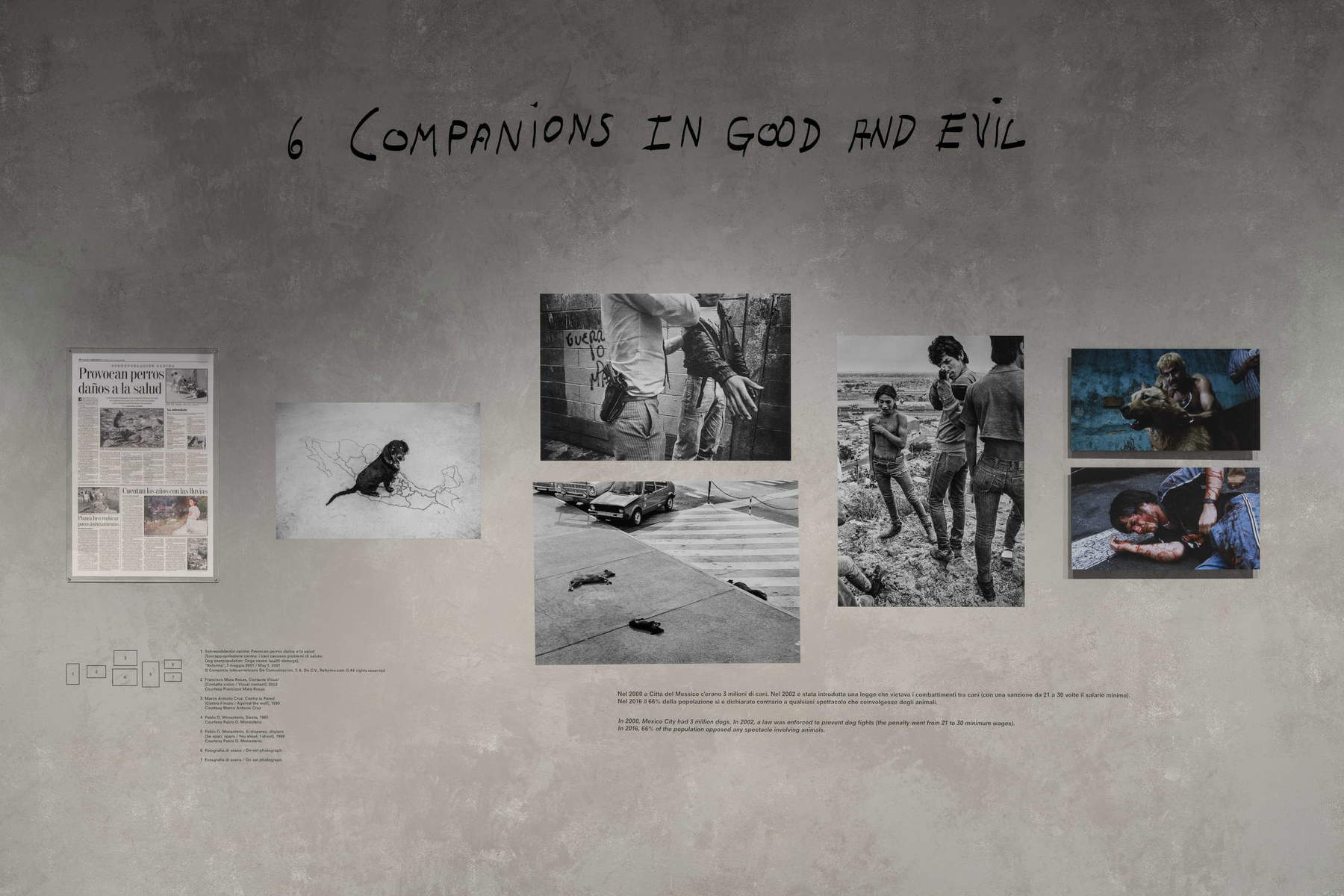

Complementing the exhibition, on the upper floor of the building, a visual and sound installation conceived by Mexican writer and journalist Juan Villoro, entitled Mexico 2000: The Moment that Exploded, delves into the Mexican social and political context at the beginning of the new millennium. An interactive audio track and an extensive collection selected by Pablo Ortiz Monasterio of newspaper pages and documentary photographs taken by leading photojournalists of the time, such as Paolo Gasparini, Graciela Iturbide, Enrique Metinides, and Pedro Meyer, document the recent history of the Mexican capital. The year 2000 was a pivotal moment for Mexico: after 71 years in power, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional had lost the presidential elections and the country was preparing to experience democracy. At the same time, the Mexican reality presented itself as a paradoxical landscape characterized by inequality, corruption, and violence, by the coexistence of Aztec stronghold ruins with contemporary ones, by legacies of Aztec religiosity blossoming into a syncretic faith that was often sentimental, by waves of protest, by the fragility of any form of sociality (from the family to the political system), by the precariousness of a largely underground economy pitted against millionaire private monopolies, by the omnipresence of television and its new idols in dilapidated dwellings lacking essential amenities such as hot water.

In this environmental format (a succession of thematic rooms to be walked through with an audio guide), what at first glance might seem to be a didactic apparatus is proposed as a poetic journey through images and words to the places where the narrative fabric of Amores Perros takes shape, without which it would have been unthinkable. The photographic exhibition is divided into twelve chapters that plumb with emblematic images the repercussions of the country’s momentous events in the hidden spaces of the capital where life flows differently than the official narrative, highlighting references to the themes addressed by the film with the inclusion of stills extracted from the film. Among the most powerful images are the portraits of armed teenagers by Pablo O. Monasterio, the series of fatal accidents photographed by Enrique Metinides, the earliest of which date back to the 1950s (in advance of Andy Warhol’s famous shots of similar subject matter taken starting in 1963 on the streets of New York), theimage by Pedro Valtierra, dated 1998, in which a petite Chiapaneca woman fends off a soldier with her bare hands during clashes between the EZLN and pro-government paramilitary groups, and Paolo Gasparini’s urban shot through the cracked windshield of a cab, which he intentionally employed to construct the intense visual metaphor of eye-breaking violence. The choice to present the photographic prints (all in black and white except for the film frames) in a habitable arrangement is effective in making intelligible the unfolding of the historical narrative in its synchronic aspects and constitutes an interesting proposal for a documentary-like arrangement. More engaging than the classic synoptic panels, this presentation, in which the images have been reprinted with a uniform texture, comes somewhat at the expense of enhancing the value of the individual pieces and their original material specificities, implicitly declaring the subalternity of an exhibition project that, instead, would have had every qualification to subsist even in the absence of the more “emblazoned” accompanying exhibition.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.