Even an acclaimed contemporary artist like David Hockney can perhaps be included in the ranks of Giovanni Battista Moroni’s admirers. But even should one deem it excessive to burden him with the label of enthusiast, it is still safe to say that Hockney figures among those who, over the centuries, have appreciated the Bergamo painter’s extraordinary gifts: “about 1553,” Hockney wrote in his book Secret Knowledge devoted to the techniques of artists of the past, “Moroni painted the most elaborate of dresses, with a bold design that is always credible on its surface, following the folds and with subtle light and shadow all depicted.” Indeed, the visitor who enters a museum and sees a painting by Moroni for the first time, perhaps without knowing the artist and without expecting it, is struck by those clothes that give back tactile sensations so concrete, so intense, so incredibly real that it almost seems as if the fabrics have materialized there, inside the room, in front of the eyes of the viewer and would like to reach out a hand to make sure that they are only painted. There are no tricks: it is the talent of one of the greatest portrait painters in history. A specialist so attached to his genre that he turned out instead to be an ordinary painter, average if not even mediocre, when he dealt with things that were not exactly congenial to him (altarpieces, for example). However, when he found himself in front of a model posing for him, Moroni revealed himself to be an artist endowed with an uncommon sensitivity and prodigious mimetic skills, attentive to the truth like almost no other of his colleagues, and therefore a thoroughly modern artist. And it is to him that the Gallerie d’Italia in Piazza Scala is dedicating this year’s winter exhibition, Moroni. The Portrait of His Time, curated by Simone Facchinetti and Arturo Galansino, who have already worked together on other exhibitions centered on the painter from Albino. In Milan, however, it is different: never had an exhibition on Moroni reached a comparable scope and comprehensiveness.

A significant part of Moroni’s known output has been gathered here, in the rooms of what was once the headquarters of the Banca Commerciale Italiana. They are mostly portraits, as one might expect. Yet it is an eventful exhibition. This is partly because Moroni is a surprising painter. His portraits do not have the official, grave register of Titian’s portraits, nor the italic shudders of Tintoretto’s portraits, nor the almost informal intimacy of Lorenzo Lotto’s portraits, the painter Moroni most resembles. Moroni’s portraits are astonishing for their stunning realism, capable of surpassing even that of Lorenzo Lotto, for the acumen of the psychological investigation, for the credibility with which the artist restores every single element to the viewer: fragments of skin, pieces of silk caressed by light, two-day-old beards, jewelry, hair, lace, wrinkles, lips, reflections. Longhi had placed Moroni along a tradition that started with Donato de’ Bardi and Vincenzo Foppa and went all the way to Caravaggio. Mina Gregori, on the other hand, spoke of a “Lombard eye” and attributed to him the ability to have developed a particular, northern figurative culture capable of mediating between the Brescians (Moretto, who was Moroni’s master, and then obviously Savoldo and Romanino) and Lorenzo Lotto, Moroni’s second polar star. A figurative culture that attributed supreme value to the ability to spontaneously perceive optical phenomena without passing through the abstracting medium of drawing, but trying to discover them, if anything, by means of light. That is why it is not far-fetched to consider him a forerunner of Caravaggio. Moroni was an artist who observed reality for what it is, and put his keen powers of observation at the disposal of his patrons.

And the underlying goal of the Milan exhibition is simple: to give the public an account of who Moroni was, what contribution this artist made to the culture of his time and to the history of art. It is necessary, then, for it to be essentially an exhibition of portraits. The visitor, however, will not come out bored, and not only, as mentioned above, because Moroni is an astonishing painter, but also because the curators have been able to construct an itinerary, accomplished and dynamic, in nine chapters, without following a strict chronological order, but gathering the works by themes, useful for providing the public with the coordinates to orient themselves in the production of the painter from Bergamo. The result is the figure of a talented, sensitive, innovative painter, appreciated by patrons, yet then relegated, over the centuries, to a marginal role, because the portrait has long been a genre considered secondary. And full recognition, for a pure portraitist, is a difficult goal to achieve. He has not been helped by his altarpieces, painted overwhelmingly for tiny provincial parishes scattered throughout the Bergamo area. He was not helped by a coeval artistic literature rather stingy toward him. Moroni’s rediscovery is a purely twentieth-century affair. And today we are able to appreciate him for having been a new man of an extraordinarily fruitful season.

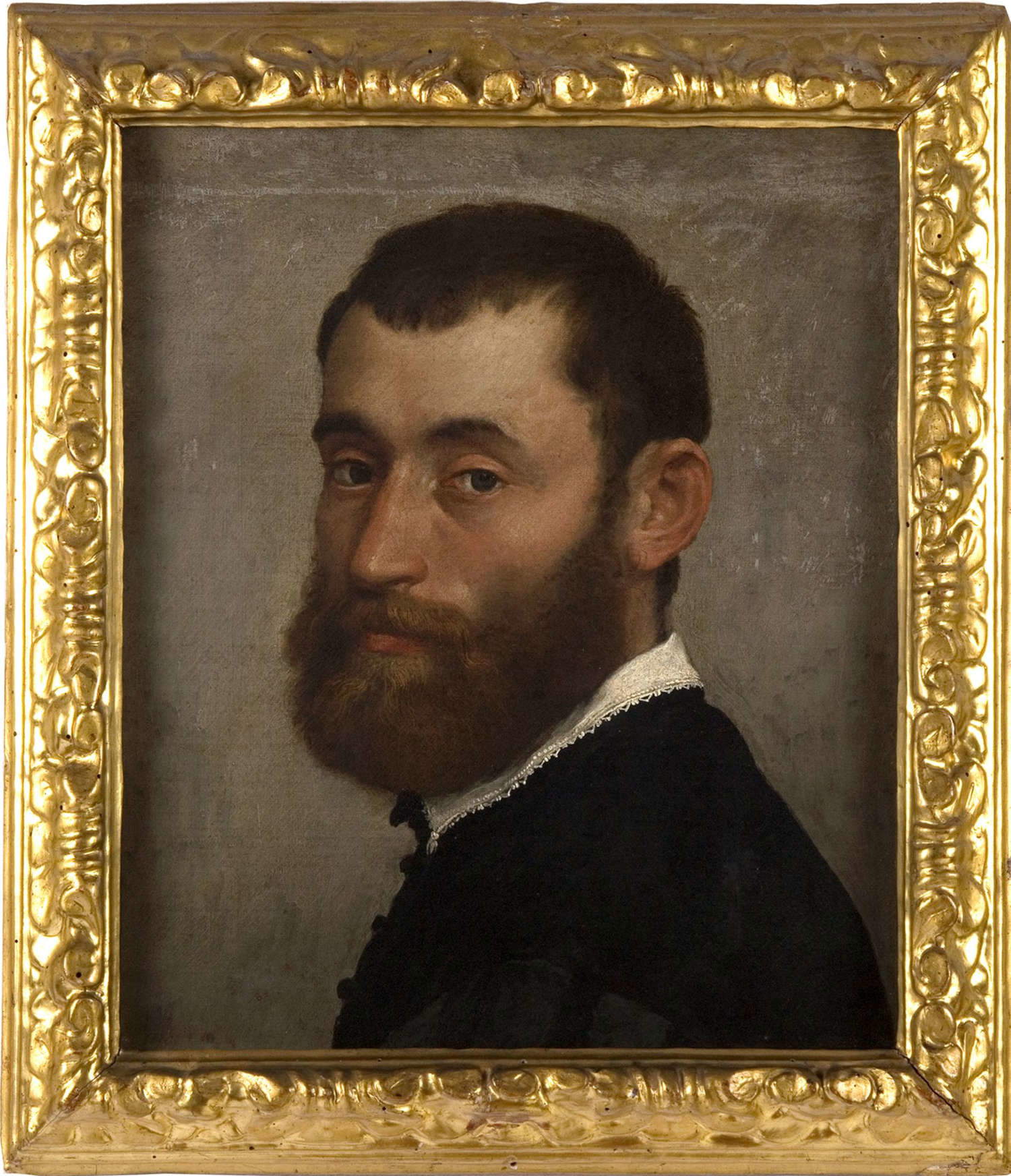

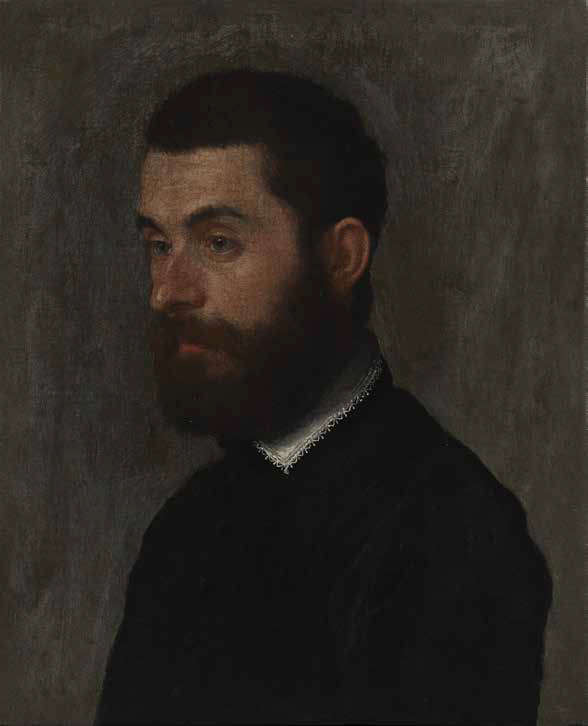

Moroni’s personal season begins instead in the 1630s, when the artist’s family moved to the Brescia area and he entered the workshop of Alessandro Bonvicini, il Moretto: this is where the exhibition begins, from the large central hall of the Gallerie d’Italia where Moretto’s altarpieces have been arranged, starting with the Marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria from the church of San Clemente in Brescia and the Madonna and Child between Saints Eusebia, Andrew, Domneone and Domno, both fundamental texts for the young Moroni, who starts his own path by copying the master’s inventions. The review has gathered some sheets that offer evidence of this practice, in which the painter would continue to practice for some time, partly to refine his technique, and partly to enlarge his repertoire of models, which would come in handy should he receive commissions for some altarpiece. Not least because, at the time of the Council of Trent, artists were required to be more pragmatic than original: this is demonstrated by the altarpiece that Moroni painted in 1551 for the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Trent, perhaps the best of his career, partly because it is so close to Moretto’s compositional solutions and stylistic gimmicks that it was long misunderstood to be a work by the Brescian master, and only the recent discovery of some indisputable documents has shed light on Moroni’s name. At these chronological heights, however, Moroni is already an independent portraitist, and we must therefore rewind the tape to return to the time when the artist began to look around. We are not quite sure when Moroni began to specialize as a portraitist, but a few firm points exist: first, the Bergamasque’s first portraits date back to the 1640s. And then, these early trials appear to be illuminated by the beacons of Moretto and Lorenzo Lotto, the two poles within which Moroni’s portraiture moves from the outset: we can perhaps go so far as to assume that he also knew Lotto in person, not least because the Venetian was a friend of Moretto’s. The second section of the exhibition focuses on these contributions, without, of course, neglecting others (e.g., Andrea Solario or Dürer), none of which, however, can be compared in importance to the two supreme models: taking it to extremes, we could say Moretto for layout and Lotto for attitude. The Portrait of Giulio Gilardi, one of the most interesting loans in the exhibition (it comes from the San Francisco Fine Arts Museum) represents with supreme effectiveness the way Moroni had to look at Moretto and Lotto: The three-quarter pose, the idea of having the hand closest to the observer rest along the hips, the pronounced naturalism (the exhibition produces here a timely comparison with a work by Moretto shortly before, the Portrait of Gerolamo Martinengo of Padernello), all hark back to the former, while the setting, a precisely described domestic interior, preserves anecho of Lotto’s approach, “capable of establishing a relationship of special confidence with the effigy and surprising him in his most secret intimacy” (so Francesco Frangi), and in this case the comparison with Lotto’s very famous Portrait of a Young Man , housed in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, comes in handy. However, the proximity to Moretto at this stage is still evident: the Portrait of M.A. Savelli (so far unsuccessful attempts to give a more precise identity to the personage indicated by the inscription), coming from the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon, has in the past been thought to be the work of the Brescian. And that we are dealing with a portraitist still in his early days seems even more evident if we look at the two small portraits in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena, truthful in their naturalism, but still far from that vivacity of which Moroni was to show in the years to come.

It is, however, almost certain that Moroni, despite his still rather strict adherence to the manners of the master (though, as we have seen, tinged with accents of marked originality), had already made a name for himself, if at the beginning of the 1950s he was in Trent in the service of the Madruzzo family, one of the most powerful families in the city, and precisely at the time when the Council was in the thick of things. Trent was a fundamental junction in Moroni’s career, for here the artist had the opportunity not only to work for an important patron, and thus to put himself on display, but also to measure himself against the great international portrait painters, starting with theDutchman Anthonis Mor, whose Portrait of Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle and Portrait of Giovanni Battista Castaldo are featured, and Titian, who arrived in the exhibition with the Portrait of Giulio Romano and the Portrait of the Prince-Bishop Cristoforo Madruzzo (and, a little further on, with the incredible Portrait of Filippo Archinto, a mysterious object because of the veil in front of the personage, which Francis Bacon may have remembered centuries later): two artists who were setting the canons of official portraiture. Slightly more palatial and sophisticated Mor, more spontaneous and animated Titian, who evidently becomes Moroni’s point of reference if one admits that the probable Portrait of Michel de l’Hôspital in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana owes some debt to the monumental portrait of the prince-bishop, which the painter from Albino must have seen in Trent (Mina Gregori instead identified a reference in Moretto’s Ritratto virile , painted in 1526, now preserved in London: unfortunately not in the exhibition). Also strong are the similarities between Giulio Romano’s Titian portrait and Moroni’s Portrait of Alessandro Vittoria , an extraordinary masterpiece of vitality, immediacy and naturalism, among the pinnacles of the entire Moronian catalog: the character, the greatest Venetian sculptor of the sixteenth century (and thus an artist like Giulio Romano), is depicted in the same pose as his colleague, three-quarter-length, with his face turned to the viewer’s left, and with the object of his art in his hands. If, however, Titian’s portrait retains some measure and is presented to the eyes of the viewer cloaked in a certain formality, Moroni’s appears to us to be decidedly more animated: it seems that Alessandro Vittoria has just turned around, quickly; the look in his eyes, lively, exudes firmness and pride in his work, a pride further underscored by the firm movement of his hands and arms, with his muscles tensing to hold the statue steady. A lesson Moroni had borrowed from Lorenzo Lotto: every movement of the body is a reflection of a state of mind, even a gesture conveys an emotion.

The typically Lottesque idea of entering into the subject’s private life is not abandoned even in the portraits of men of power, who indeed evidently showed an appreciation for Moroni’s ease if in these paintings it is possible to appreciate the most varied attitudes varî, as the sequence of the three portraits of podestà (the administrators of the Republic of Venice in the territory) attests, namely the unidentified one from the Carrara Academy in Bergamo, the one of Antonio Navagero and the one of Jacopo Foscarini: these figures, “despite wearing the official clothes that designate their rank,” the curators write, “are filmed in approaching and weekday poses and attitudes, sometimes even looking at us with a friendly air.” Poses and attitudes perhaps ill-suited for display in offices or public spaces: we have no idea where they were displayed, but it is likely that they adorned the private residences of these politicians, so much so that in many cases their history has continued in the collections of their descendants. The next section of the exhibition, the fifth, is devoted to the “natural portrait,” an issue explored in depth by Paolo Plebani in his catalog essay, since the subject of intense debate at the time: should the subject be portrayed as faithfully as possible to the natural datum, or should some form of idealization be introduced into the portrait? The line that would be most successful is the idealizing one, and this to some extent also explains part of the critical failure of Moroni’s portraiture, despite the fact that the portrait had known precisely during the Renaissance, and particularly in the sixteenth century, an increasing importance, linked, Plebani himself recalls, “to various factors, including the cult for the individual, the theme of memory and the celebration of illustrious men.” And this explains why the portrait genre, in Moroni’s time, is successful not only among sovereigns and high prelates, but also among less high-ranking figures, as the long theory of portraits in the fifth section of the exhibition attests.

These are paintings that are astonishing for their naturalism, to which Moroni remained faithful throughout his career, without seeking any kind of mediation, and indeed making his investigations of the subjects ever more acute: compare, for example, the Portrait of a Young Man in Profile in the Carrara Academy with the two portraits in Siena, given the identical layout. How Moroni’s research into the character’s expressiveness has changed, however, within a decade or so! And one could then linger on the “good-natured irony” (so Facchinetti) with which Moroni tries to convey the characters of his characters, a gallery of individuals who appear so close to us: the sly eye of the Lateran canon Basilio Zanchi (and his tonsure, and barely noticeable beard painted with a precision we would say photographic), the sullen gaze of Lucia Vertova Agosti (and the lenticular accuracy with which Moroni depicts jewelry and lace), the serious firmness of the Portrait of a Twenty-Nine-Year-Old, the somewhat tedious attitude of Pietro Spino. Many of them are caught in the act of holding the sign with the index finger in a book they are reading, partly because the book at the time was a sort of status symbol, and to be portrayed in the act of reading conveyed an image of prestige and respectability, and partly because this pose suggested naturalness and movement. Particularly curious is the portrait of the condottiere Bartolomeo Colleoni, which Moroni painted from a late 15th-century image, and then in turn the basis for a later engraving: curious because Moroni tries his hand at the depiction of a dead personage, attempting to strive to infuse him with a breath of life, but the undertaking is arduous and the result is certainly not one of the most successful things from an artist who was able to give his best when he had a flesh-and-blood model in front of him.

![Anthonis Mor, Portrait of Giovanni Battista Castaldo (c. 1550; oil on panel, 107 x 82.20 cm; Madrid, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, inv. 291 [1976.65]) Anthonis Mor, Portrait of Giovanni Battista Castaldo (c. 1550; oil on panel, 107 x 82.20 cm; Madrid, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, inv. 291 [1976.65])](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2540/antonis-mor-ritratto-castaldo.jpg)

In the next section we abandon portraiture for a moment for a lunge at altarpieces, and the comparison between Giovanni Battista Moroni and his two models is merciless: his religious enterprises retain little of Moretto’s inventive felicity or Lorenzo Lotto’s eccentric exuberance, qualities evidenced in the exhibition by Moretto’s St. Nicholas presenting Galeazzo Rovellio’s pupils to the Virgin and the latter’sElemosina di sant’Antonino . Closely dependent on Moretto’s St. Nicholas is the Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine , which, however, appears undoubtedly flatter than its model (and the composition less successful), while certainly better is the polyptych from the church of San Bernardo di Roncola, which follows the pattern of Titian’s Averoldi Polyptych, a work Moroni must have known very well (and the figure of the risen Christ from the Averoldi Polyptych is also taken up in the Resurrection in the exhibition). However, Moroni also manages to pour his qualities as a portrait painter onto altarpieces, where in the sacred scene it is necessary to add the image of a patron: this is what we see in a couple of works that are far from perfect, but nonetheless singular, namely theLast Supper in Romano di Lombardia, where we observe a man portrayed standing behind St. John (identification is not easy, but it is likely to be the parish priest Lattanzio da Lallio, who requested the painting from the artist), and the late altarpiece with Don Leone Cucchi in contemplation of St. Martin, whose protagonist is the provost of Cenate San Martino in whose parish church the altarpiece is kept.

Midway between the portrait and the altarpiece are some works that reflect the climate of the time and to which the seventh section of the exhibition is dedicated: they are paintings intended for prayer in mind, a practice that had spread throughout Italy in the mid-sixteenth century in the wake of Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises , first published in Latin in 1548. The book contained a number of practical methods of prayer, including mental prayer: the faithful were spurred to pray in silence, if necessary imagining scenes from sacred texts with their imagination, and for this practice an image to contemplate could be helpful. The intense Portrait of a Devotee in Contemplation of the Madonna and Child, for example, must be read in this sense: the sharply characterized image of a devotee who is praying and has a vision of the Virgin with the baby Jesus in her arms. However, the structure of the painting could have been more complex, such as that of the Devotee Contemplating the Baptism of Christ from the Etro Collection, where the imagined scene is separated from the portrait by a sort of balustrade, or like the painting with the Two Devotees praying before the Madonna and Child and St. Michael the Archangel, a painting in which, Facchinetti writes, “two different psychological attitudes coexist, of immersive participation and active contemplation of the devotee couple.”

The last two sections of the exhibition return to Moroni’s portraiture to focus on portraits as a means of gaining a closer understanding of the society of the time. Moroni, beginning in the 1950s, became the favorite portrait painter of Bergamo’s high society, and observing his portraits is like entering the palaces of the time, it is like turning one’s gaze to the customs of mid-sixteenth-century Bergamasque nobility, it is almost like getting to know at first hand the subjects that the painter, beginning in this period, painted with a new verve, especially coloristic verve, as evidenced by the masterpiece of his last years, the Portrait of Gian Gerolamo Grumelli, also known as The Knight in Pink, a sumptuous full-length depiction of’a young nobleman adorned in a rich Spanish-style, coral-red dress with silver thread decorations, and as is also well seen in the Portrait of General Mario Benvenuti, who wears gleaming armor on which glistening reflections of light linger. The Carrara Academy’s Portrait of Isotta Brembati , the curators note, is useful for touching on the theme of shadow play in regard to which Moroni has “always had a marked sensitivity,” modifying over time his way of rendering shadows on canvas: in the 1950s the artist, Facchinetti and Galansino suggest, “does not define the limits of the shadows but frays them, connoting them with an irregular mark, obtained with different intensities of dark tones” and thus succeeding in obtaining a “palpitating vibration” such as the one that animates the portrait of the poetess. Later, the artist would also indulge in more unusual deformations and distortions, such as those of the completely unrealistic shadow of the large Portrait of Bernardo Spini (exhibited in Milan together with that of his wife Pace Rivola), almost a second protagonist of the painting, similar to the shadow of the Portrait of Pietro Secco Suardo that can be admired in the last section, all centered on the fashion of black in theclothing of the time, and built, however, around the only character dressed in white, the Tailor of the National Gallery in London, one of the most famous works of Moroni’s production, as well as a genuine and vivid image of ’a professional caught in a moment of his work (on a black cloth, already marked with chalk to be cut with the scissors that the tailor clutches in his hands), a work that, Berenson said, “as to form and action wins the excellent Moretto.” It is his gaze that communicates, with serene and thoughtful composure, his own tranquility, full self-awareness, and satisfaction with his craft and the status he has achieved: this tailor was not a nobleman, but he could still commission his portrait from one of the most sought-after specialists of the time.

It is convenient to point out that Moroni’s portraits obviously offer a kind of figurative account of Bergamasque society of the time: through the subjects captured by Moroni, the objects they exhibit, and especially the clothes they wear, it is possible to learn about the fashions of the time, the economic dynamics, and even the laws, since many legislations in those days provided for strict norms on clothing, prescribing the clothes to be worn and those to be avoided for reasons of decorum and to curb the ostentation of luxury. The black with which the exhibition closes, for example, besides being for a painter a difficult color to reproduce (Moroni’s unquestionable qualities are also appreciated where the Bergamasque artist succeeds, with supreme skill, in conveying all the declinations of black fabrics, with its reflections, iridescences, folds, thealternation of bright and opaque passages, the modulations of light that linger on fabrics, silks, satins and whatnot), is also a kind of open book on the fashions and culture of the time, as Roberta Orsi Landini well illustrates in her essay in the catalog, all dedicated to the clothing of Moroni’s characters: we thus learn, for example, that black, far from being associated only with mourning or in any case with feelings related to sadness, indicated composure and gravity and thus alluded to the moral qualities of the wearer, but it was also considered to be the proper color of nobility and thus was a symbol of honorability, and consequently it was also accompanied by a kind of literary ennoblement that pervades many texts of the time (beginning with Baldassarre Castiglione’s Cortegiano , where we read that the clothes of the perfect courtier should tend “a little more to the grave and restful than to the vain” and that consequently they should be black, as a color associated with these qualities).

An exhibition, then, that also opens to interesting cross-readings. It is not, as mentioned in the opening, the first ever exhibition on Moroni, who in any case in the past has enjoyed a certain exhibition fortune, at least since, at the 1953 exhibition on the Pittori della realtà in Lombardia , organized by Roberto Longhi, the Bergamasque was present with no less than thirty-five paintings to follow up on the Longhian idea that he was a precursor of Caravaggio. Moroni at that time had already largely re-emerged from the underground river of collecting (which, starting in the seventeenth century, albeit amid ups and downs, had never ceased to take an interest in his works, which have long been true and sought-after cults for fans of the genre), and had become an object of interest for scholars and even the public, as certified by the exhibitions that between Bergamo and London were dedicated to him in 1978, the year of the four hundredth anniversary of his death. A forerunner of the Milan exhibition is the one in Bergamo in 2004 (centered, however, only on the production of the 1960s and 1970s), also curated by Facchinetti, just like the London exhibitions in 2014 and New York in 2019, compared to which, however, the Gallerie d’Italia exhibition represents a’much broader occasion, in which not only Moroni’s story is retraced with precision and along the entire span of his career, but is also punctually contextualized, dropped into the artistic, cultural and social context of the time, and enriched with lively comparisons, which alone would be worth the admission. A monograph organized according to a rigorous scientific project that is at the same time very modern, for the cut that has been given to the exhibition itinerary, for the way Moroni is narrated, for the way the layouts have been organized as well as the tools that accompany the itinerary. That is why Moroni . A Portrait of His Time is one of the most important exhibitions of the year.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.