The 1980 Venice Biennial catalog inserts Cioni Carpi (Eugenio Carpi de’ Resmini; Milan, 1923 - 2011) in a group of artists who “have worked since the late 1960s with insistence on the media of large-scale communication, experimenting with a different, redifinitory and creative use of them.” Shifting the temporal terms, one could apply the same definition to frame the work of Gianni Melotti (Florence, 1953) as well: he and Carpi are artists who find in the contamination of media, in the experimental attitude, in the desire to investigate original forms of expression the major points of contact. Carpi and Melotti are the protagonists of two separate exhibitions at the Ragghianti Foundation in Lucca, which started in the fall but was forced to close its doors prematurely due to the health emergency, and then reopened a few days ago (it will close on Feb. 19). Two different exhibitions, with two separate catalogs, two autonomous curatorial projects and two clearly divided paths, but united under a single title, The Adventure of New Art. The Ragghianti Foundation confirms its vocation as a center for the study of phenomena that are more tucked away and far from the spotlight but indispensable for the development of certain fundamental lines of Italian art, and with the double fall exhibition it guides the public through the recovery of two of the most innovative personalities of that fervid period from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s. That is, probably the last era during which Italian art was at the center of the world.

These are two difficult exhibitions, undoubtedly, two exhibitions that are bound to be hostile to the general public: first, because to approach the discourse opened by Angela Madesani (curator of the exhibition on Cioni Carpi) and Paolo Emilio Antognoli (who, on the other hand, is responsible for curating the review on Gianni Melotti) requires at least basic knowledge of the art-historical context. Which for Cioni Carpi is, for example, that of the nascent Narrative art, of which the Milanese artist was one of the pioneers on an international scale. We are talking, in essence, about photographs and words that combine to set up a narrative that has the most diverse purposes: for Carpi it is often a matter of working on memory, given also his past as a Nazi-fascist persecuted (his father Aldo, another great artist, was imprisoned in Mauthausen, while his younger brother, Paolo, lost his life at the age of eighteen in Flossenbürg). Add to that the difficulty of framing an extremely elusive artist, who refuses any label: even associating him with Narrative art alone becomes reductive. Because Carpi never stuck to the usual research, because he was an almost stateless artist (many were the places he toured: Milan, Port-au-Prince in Haiti, Montréal in Canada, then Milan again, and then the United States), because different were the genres he experimented with. The particular use he made of himself makes him almost approachable to Body Art: Lea Vergine even included him in her seminal essay Body Art and Similar Stories. Gianni Melotti also eschews definitions: in his case we need to go back to the Florence of the 1970s, where the conditions for the birth of video art were founded, and Melotti stands as one of the protagonists of these processes. From the studio where he worked, art/tapes/22, also passed Bill Viola, who for a year and a half collaborated with Melotti and the other artists who frequented the studio.

Difficult, then, because these are not two anthological exhibitions: they are two focuses on very specific portions of the two artists’ activities. That is, the 1960s and 1970s for Cioni Carpi (who would later permanently retire from the art scene in 1989: and after this year, consistent with his choice, he produced nothing more), and the 1970s and 1980s for Melotti. For Carpi it basically goes from the Palimpsests of the early 1960s to the experiences preceding the 1980 Venice Biennale, which is not part of the exhibition itinerary. For Melotti, on the other hand, it goes from 1974 to 1984, which is the period identified as that of the beginnings of his activity. And for both it is basically a matter of defining the contribution given to the artistic research of those years: this is one of the objectives of the two exhibitions.

|

| Hall of the exhibition on Cioni Carpi |

|

| Hall of the exhibition on Cioni Carpi |

|

| Hall of the exhibition on Gianni Melotti |

|

| Hall of the exhibition on Gianni Melotti |

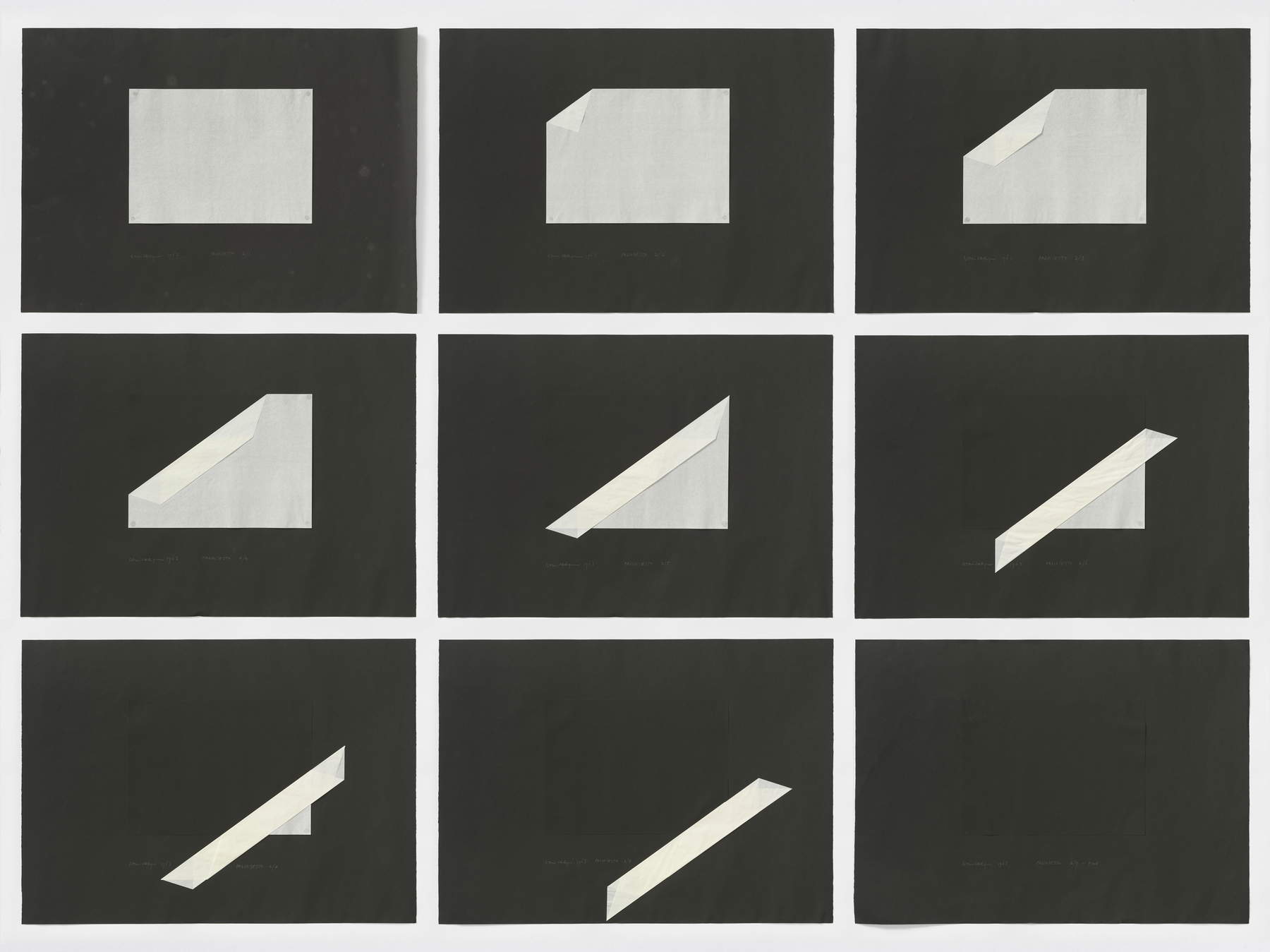

A quote from gallery owner Romana Loda given in the catalog can help the visitor in sketching the outlines of the figure of Cioni Carpi: “A man and a free artist, Cioni Carpi never wanted to produce art, in the usual sense of the term, but to ’live&rquo; (with quite another courage) art, through the realization of what Artaud called ’the constant sperdimento of the normal level of reality,’ his was an aspiration for harmony between ’being’ and doing, which transcends all the possible betrayals that life holds for each one.” A first evidence of this harmony between “being” and “doing” comes with Palimpsest 2 at the opening of the exhibition: Carpi himself defined the Palimpsests as works marked by a “visual-mental connotation denoting a psychological situation that can come to be determined both at the level of consciousness and at the level of the unconscious, either in combination or at successive moments.” It is a kind of sequence that captures a succession in becoming, in progression: there are palimpsests composed of photographs or, as in the case of the exhibition, works balanced between painting and relief, with a sheet of paper caught in the act of being folded through nine successive steps. Carpi’s reflection is centered on cognitive processes; it is an investigation into the rules governing perception: each passage destroys the previous one, creating new images and consequently giving rise to a different perception of the same image. Somewhat like when, the artist himself explained in one of his articles, one experiences live a place that until then one had only imagined. Hence also the use of the term palimpsest according to its pure etymological root (“erased again”). Palimpsests constitute a fundamental transition toward the Narrative Art experiences of which the Lucca exhibition provides pregnant examples.

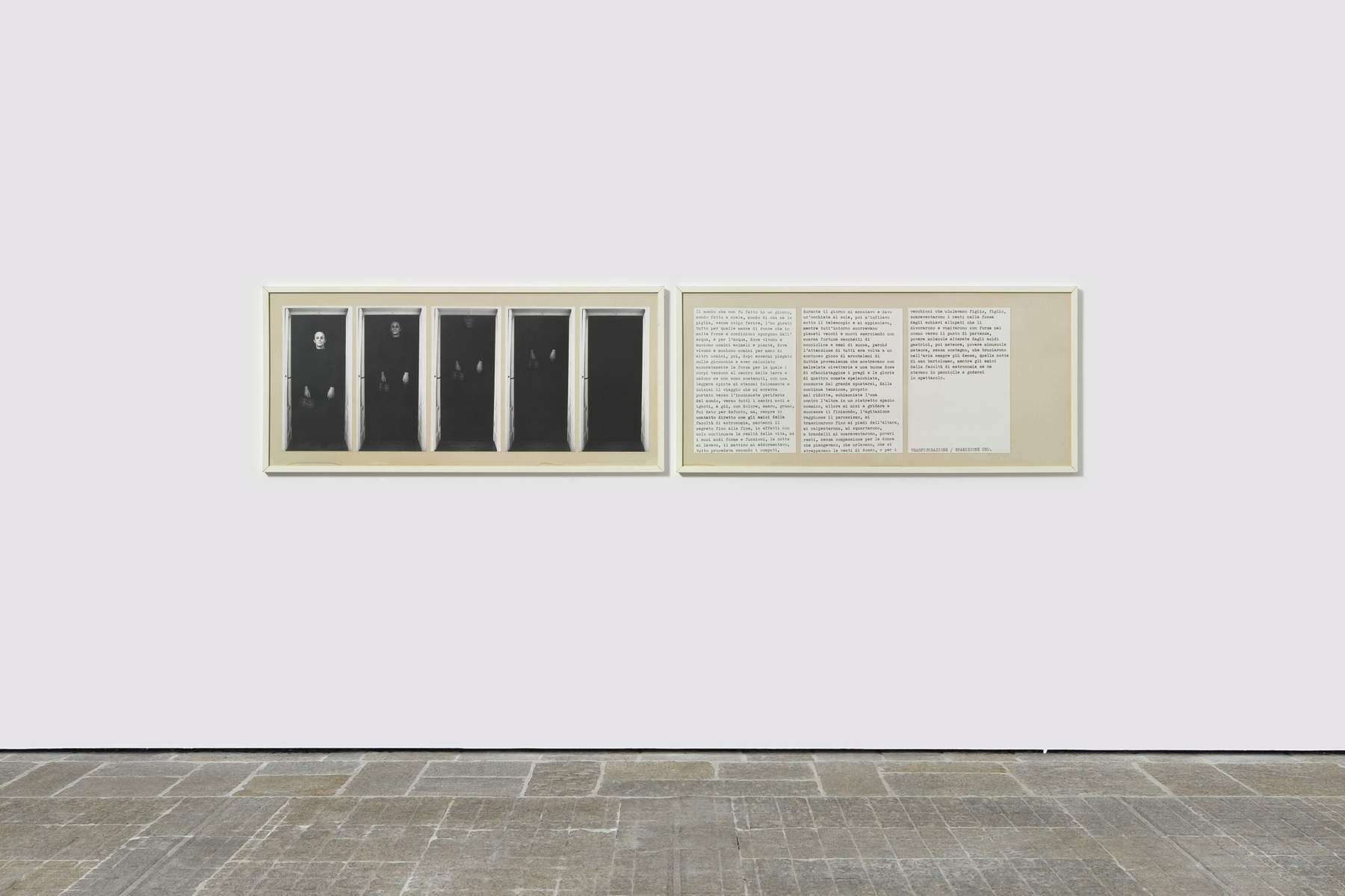

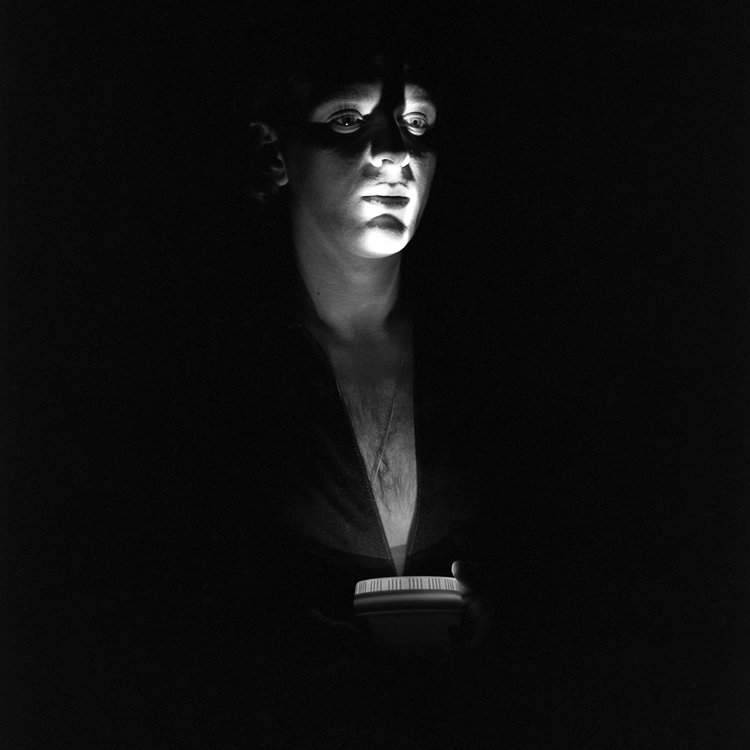

Works such as the Transfigurations or Me ne tornavo ai luoghi sfatti della memoria fit into this strand: “photography, an artistic medium,” explains the curator, “in this sense is used as a complementary or additional visualization of a narrative or research. A linguistic unity is created.” It should be noted, to use Angela Madesani’s words again, that writing, in Cioni Carpi’s works, “is not used as a caption to the image, but as an autonomous table within the work.” “I used to return to the unmade places of memory,” reads the text placed under the sequence of images that see the artist sit at a table and then disappear behind a jar with a plant inside, according to a procedure that echoes and reworks the Palimpsests, “[.] then I destroyed them with an effective carpet bombardment without bothering with a fast disruptive black nebula devoid of miscalculated cosmic motion that almost fell on my head and left me speechless, and it was there that I lost my reason, or little missed it, and everything I held back with difficulty.” Again the relationship between memory and person emerges from Cioni Carpi’s research: for the artist, even remembering the exact place where one was once, it would be impossible to recreate the same situation, which is why memory is sustained solely by the photographic trace. It could be said that, as it was for Roman Opalka, also in Cioni Carpi it is the material object that retains the passage of time: and if Opalka’s goal was to arrive at an anti-self-portrait of himself that was completely white, adding a percentage of white to his effigy from time to time over the years (he died before he succeeded), Cioni’s “anti-self-portrait” is one in which the artist depicts himself, for example, as a “shadow” or as a "young dog." And this is because the element that connotes Carpi’s reflection is the idea that memory does not refer only to the past: any element is enough to activate it in the present. Anything can generate memory, transforming itself in turn into "memory of memory," the artist asserted. A reflection not so distant from thatanachronism of images that Didi-Huberman would later talk about, if you will.

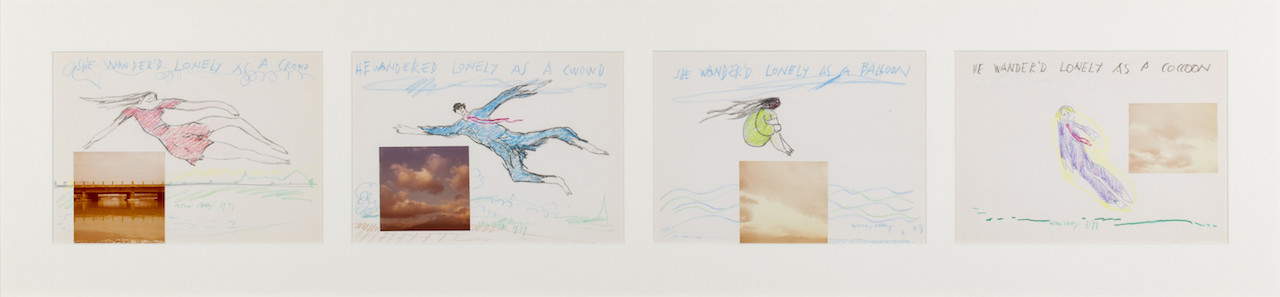

This is one of his contributions toconceptual art, but it has been said that Carpi has also been approached to Body Art, and the same Transfigurations, works with which the artist, wrote Giorgio Di Genova (emphasizing, moreover, his debts to the metaphysical painting of Carrà and Casorati), experienced “the impossibility [...] of knowing and knowing oneself” by progressively making himself disappear, are directly related to art that expresses itself through the use of the body. Object that can be interpreted but not known, in essence. “Cioni,” writes the curator, “is man with his doubts, dramas, and joys; he is a kind of archetype of humanity, an emblematic representation, which at the same time always emphasizes his person, immediately recognizable. He is one one hundred thousand, the protagonist of a society that could no longer be the same after the Shoah, apotheosis of human irrationality, after the atomic bomb.” The exhibition concludes with the Sehspass (a neologism of Cioni Carpi’s: it literally means, from the German, “visual amusement”), interventions on images through the use of drawing and painting to stretch their limits, and with works on jute that, in Carpi’s intentions, relate back to the narrative modes of a work that has always fascinated him, the Bayeux tapestry, which for him was a true embroidered film. They too are divertissements in which the word expands the meaning of the images: it happens, for example, when the photograph of a clear sky becomes the “View of the Seventh Heaven.” Innovator, nonconformist, alien to any cage, capable of offering his own contribution to different art forms: this in essence is the portrait of Cioni Carpi that is drawn from the exhibition itinerary.

|

| Cioni Carpi, Palimpsest 2 (1963; tissue paper on cardboard, work in 9 parts, 50 x 68 cm each; Mendrisio, Pansa Collection) |

|

| Cioni Carpi, Transfiguration / Disappearance one (1966-1974; text and photographs on paper, work in two parts, 44 x 99 cm each; Mendrisio, Panza Collection) |

|

| Cioni Carpi, Portrait of the Artist as Shadow on the Wall (1957-1975; black and white photograph, 50.5 x 50.5 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Cioni Carpi, Sehspass: She went down to the seas again, detail (1979; mixed media on paper, work of 23 color plates and one explanatory plate, 20.5 x 29.5 cm each; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Cioni Carpi, View of the Seventh Heaven, detail (1979; photograph and tempera on jute, 10 x 148 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

Cioni Carpi and Gianni Melotti have never met: yet, walking through the two rooms of the exhibition reserved for the Florentine photographer, one might think that the affinities between the two are closer than they appear. It may be a suggestion, but there is like an echo of the Transfigurations in Melotti’s 1975Self-Portrait in Double Exposure: a metamorphosis that starting from a sharp image of the artist’s face comes to dissolve through gradual decompositions. And the same could be said for a 1977 series, The Iconography and the Iconoclast, which starts with a series of photographs taken in Florence, beginning in the artist’s room, then opening outward, onto the city, and then further outward onto the hills that frame it, ending with the photographer’s self-portrait. “The point of view,” the artist wrote, “is that of the person who enters the room and, following this, begins a sort of ’filmic’ zoom-in that shot after shot brings me closer to the window and beyond the screen given by the transparent glass to take me to an exterior, my usual exterior that extends beyond a large white wall toward the distant hills to the north, where it happens to be the countryside.” Sequences that lie somewhere between photography and film (Cioni Carpi, moreover, also often used video as a means of expression especially at the end of his career), and which were described in detail by Melotti in a notebook, transcribed in the exhibition catalog. It should be noted how the title of the work, the curator explains, “oxymoronically associates both the description (iconography) and the destruction of the icon (iconoclasm), thus by association the attraction and repulsion for images.” It is Melotti’s contribution to the research on the image that was central to Italian art of the time (for example, Giulio Paolini’s Mimesis, one of the most important works of that period, precedes Melotti’s series by two years), but at the same time it is a form of expression close to Narrative Art, although it cannot be ascribed to it.

One of the purposes of the exhibition, which moreover presents previously unpublished material, lies in an attempt to emphasize how Melotti’s work constitutes a contribution that, the curator writes, “modifies the general perception” of that precise historical moment. Antognoli’s essay thus provides the extremes, situating Melotti’s contribution in a moment of fervent creativity in Florence, which in the 1960s was the main Italian center of verbovisual experimentation, and was then, in the following decade, the land of choice for artists’ cinema and radical architecture, as well as being the seat of a vital fabric of galleries that offered avant-garde art. It was in this context that Gianni Melotti trained and experimented, later joining, as anticipated, art/tapes/22, becoming its studio photographer. Melotti’s biographies recall how during the art/tapes/22 years he produced videos with some of the most important artists of the time, from the aforementioned Paolini to Jannis Kounellis, from Alighiero Boetti to Allan Kaprow, from Daniel Buren to a young Urs Lüthi. The portraits that open the exhibition give a sense of the ferment that characterized the Florentine scene, but they also offer other insights: Lüthi himself, for example, is portrayed shooting a Self portrait on video in 1974. Another photograph captures Melotti and Bill Viola doing a videotaping rehearsal. These are the first experiments in video art, which come to life in art/tapes/22, and which Melotti would continue later on, under the banner of the encounter between different linguistic registers, and also employing, on the contrary, video as a photographic medium(Foto Fluida).

The itinerary draws to a close by leading visitors through the experiments of the late 1970s, at times animated by a provocative postmodern vein (as in the case of the 32 images of mock war), at others by a postconceptual sensibility, as is the case, for example, in Due superfici, to reach the 1980s and works such as Theoretical Works, series on the tensions of couples that, Antognoli writes, “under the apparent disengagement of the subject” continue to be “a work that is still substantially conceptualist, based on the semiological and comparative analysis of the images and objects staged, in whose montage a sort of depistage from the referents was operated toward linguistic and photographic play.” It ends with the Portraits in the Net (where the net is that of the sock that the subjects of the portraits, Melotti’s friends, put on their heads, posing smiling): and the “net” is thus to be read both literally and metaphorically, as an element that binds the photographs, and thus as a relational element. Which moreover anticipates by forty years the role played by another network, that of the Internet, which will add a new chapter to the social dimension of communication.

|

| Gianni Melotti, Self-portrait in double exposure, detail (1975; series of 20 silver salts photographs, 24 x 18 cm; Gianni Melotti Archives) |

| Gianni Melotti, Lyconography and Lyconoclast (1977; installation, 9 silver salts prints, 130 x 150 cm; Gianni Melotti Archive) |

|

| Gianni Melotti, Urs Lüthi during the recording of the videotape Self Portrait (1974; Giclée print; Gianni Melotti Archive) |

|

| Gianni Melotti, Photo Fluid (1983; cibachrome photographs; Gianni Melotti Archive) |

|

| Gianni Melotti, Portraits in the Net (1982; selection from the series of 17 Polaroids; Gianni Melotti Archive) |

For the Ragghianti Foundation, the double exhibition represents a first: never before have the rooms of the Lucca center hosted two separate exhibitions at the same time, especially since one of them is dedicated to a living artist. However, it is appreciable to propose to the public a focus on two figures who took part in the lively cultural climate of Italy between the end of the 1960s and the mid-1980s (also in order to demonstrate how the panorama of the time was populated by figures who were perhaps less well-known to the public but whose research had a certain impact), highlighting above all the most original and topical aspects of their experimentation. The exhibitions were intended to be offered to the public at separate times, but were instead mounted at the same time as a result of the Covid emergency: yet, the Foundation still managed to bring them into fruitful dialogue.

Some significant data emerged in the end. Two artists who, although belonging to different generations (about thirty years of age separate them), shared an experimental approach with ways of working that sometimes, as we have seen, were not so far apart and found perhaps unexpected tangencies. Two lesser-known, but no less fascinating, actors of an era marked by a marked creative fervor, an overwhelming propensity for research, experimentation, and the contamination of languages and registers: with the rereading of the figures of Cioni Carpi and Gianni Melotti, it is above all the works on the even extreme possibilities of language and photography that are the focus. Two exhibition paths organized in a coherent and linear way, according to an eminently chronological perspective (the exhibition on Cioni Carpi is more organic), not for everyone. Two sober catalogs, set up in radically different ways (the one on Cioni Carpi is even bilingual, the one on Gianni Melotti is a sort of long commentary by the curator on the artist’s notes and notebooks), meager in their apparatuses but useful for the amount of insights and material (often unpublished) they provide to the public and scholars.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.