An exhibition on Georges de la Tour is already an event even before it opens. And the one that has been running since mid-September at the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris(Georges de la Tour. Entre ombre et lumière) was announced a few months in advance and with all the typical rhetorical paraphernalia that accompanies an event: the unique occasion, the exceptionality of something that has not happened since 1997, that is, since the date of the last French exhibition on the Lorraine artist, the reduced and rarely exhibited production and so on. That the exhibition curated by Gail Feigenbaum and Pierre Curie represents an occasion is beyond doubt: today we know of no more than about forty works by Georges de la Tour, and at the Jacquemart-André one can see twenty that are considered autograph by most critics, but the number grows to almost thirty if one also considers the dubious works, those that some consider autograph and many others do not, the workshop works executed under the obvious supervision of the master. Anyone who is inflamed with a passion for Georges de la Tour’s backlights, for those dim flames that illuminate skulls, saints, Magdalene and children blowing on glowing embers, do not delay and board a vehicle to Paris, for the opportunity to see so many works by the Lorraine artist together is one of the few reasons that would support the possibility of contemplating a visit. Even the Jacquemart-André website itself says so, persuading the user to visit the exhibition by offering three solid reasons: “a unique event,” insisting that it has been almost thirty years since so much copying of La Tour’s work has been seen in France, “more than thirty masterpieces are brought together” (and it turns out seen that this is not the case, unless one wants to reconsider the meaning of the term “masterpiece”) and the possibility of "discovering one of the most enigmatic painters of the Grand Siècle."

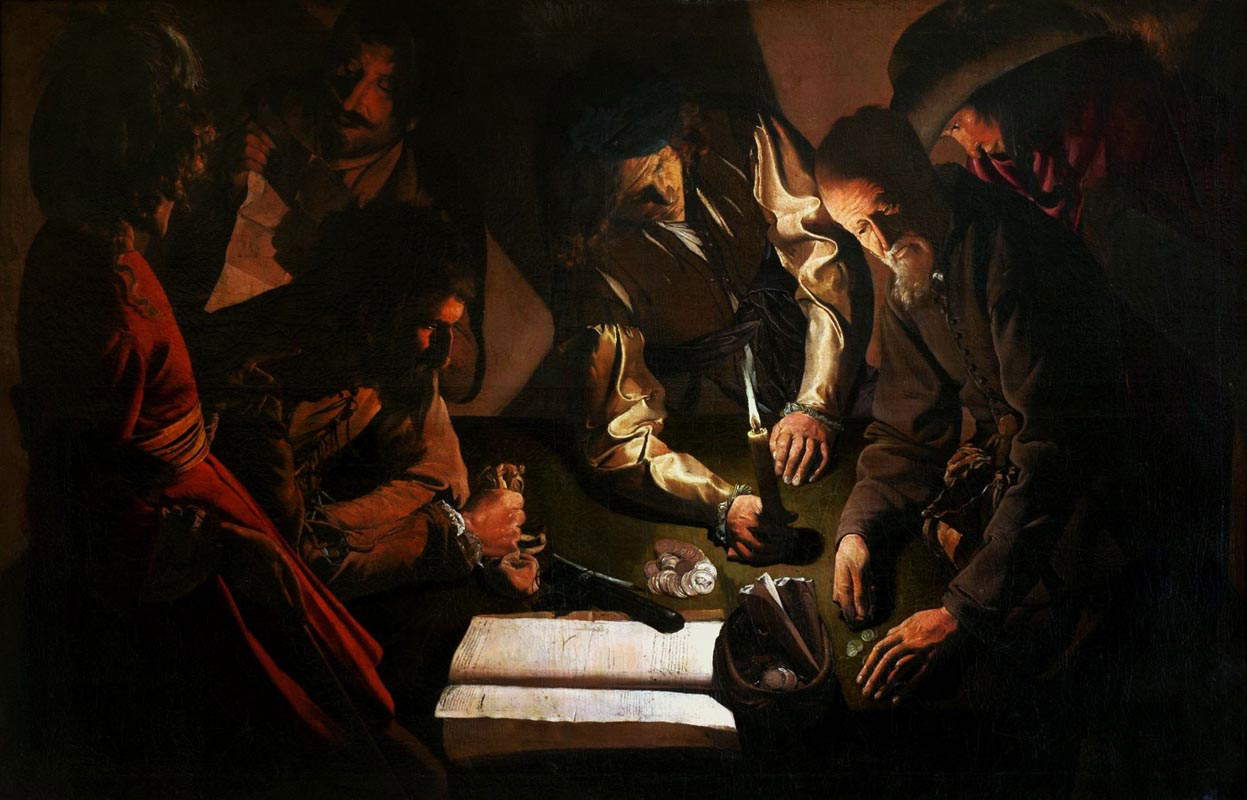

In itself, the exhibition, apart from a few novelties that will be briefly mentioned, traces without capital and indispensable variations, and in a small way, the layout of the review that was hosted in 2020 at the Palazzo Reale, curated by Francesca Cappelletti and Thomas Salamon (Feigenbaum was then part of the scientific committee). Of course: it will be said that the autograph counting deploys in Jacquemart-André’s favor, since in Milan the public could count on fourteen works definitely by the master, including some works that are not found in Paris instead (the Riot of the Beggar Musicians, one of the most intense presences in La Tour’s catalog, or the Young Man Blowing on a Dijon Tipple), and had to do without, for example, the two versions of St. Jerome, the Woman Sponging herself from Nancy, the Pea Eaters from Berlin or the Repentance of St. Peter from the Cleveland Museum of Art. Milan exhibition that, moreover, is not recalled by the room apparatuses of that of the Jacquemart-André, which, indeed, in the chronology board installed on the first wall one sees upon entering the rooms devoted to temporary exhibitions, fixes 1997-1998 as “thelast major retrospective devoted to La Tour, at the Grand Palais in Paris,” and thus leaving out the one at the Palazzo Reale, which, twenty-three years later, nonetheless marked steps forward in research on the artist, particularly on his relations with Italy. And it will also be said that the public, today, generally comes out dissatisfied with an exhibition in which the works of the main artist represent a minority fraction of the entirety of the material on display, since one tends to have the perception of a diluted itinerary, of a watered-down slop that tends to drown the pieces for which one had paid the ticket. If, however, one wants to believe that the titles of merit of an exhibition also go beyond the quantity of textbook pieces that one is able to bring together in a given venue (let the recent exhibition on Caravaggio at Palazzo Barberini be an example) and that the context still has some relevance, especially if the declared objective of an exhibition is to “place the life and work” of the artist “in the broader context broader context of European Caravaggism, in particular the influence of the French, Lorraine and Dutch Caravaggists,” then one cannot but agree on the weaknesses of an exhibition that, compared to the one in Milan, sins precisely in its attempt to reconstruct thoseinterweavings that might have brought to France themes, subjects and modes of Caravaggesque painting, because the material gathered by the curators in the rooms is too meager to attempt any form of framing. Lacking, to say, is a full-bodied lunge on the relations between Georges de la Tour and the Dutch and Flemish painters (Gerrit van Honthorst, Paulus Bor, Adam de Coster) who were often approached by him and who are indispensable to get an idea of the spread and impact of Caravaggism in the Nordic sphere, just as lacking, at least in the rooms, is a solid positioning with respect to La Tour’s possible relations with Italy. Some suggestion comes from the comparison between one of La Tour’s masterpieces, the Paid Money that arrives on loan from the National Gallery of Lviv in Ukraine, and the Concert by Jacques Le Clerc, an artist who had been in Italy ad had returned to his native France in 1622. Questions remain, however, as to how La Tour came into contact with Caravaggio’s art and who his mediators were.

The eight chapters into which the exhibition is divided, it has been said, do not differ much from the subdivision of the Palazzo Reale exhibition, which like the one on Jacquemart-André was sectioned on a thematic basis: it is perhaps the only possible approach to an exhibition on Georges de la Tour, an artist about whom not much biographical information is known and whose production, though so meager, deals with a sufficiently broad range of subjects to justify a review organized by theme. The drawback is that in the end it results in a not so dissimilar scanned exhibition: here then is a first section, La part sereine des ténèbres, which serves to introduce the atmospheres of his art, after which come those on the painting of the last, on the apostles of Albi, on the feeble light of candles as “inner light,” on “silent nights,” ending with what is perhaps the most interesting portion of the exhibition, the only one attached to a chronology, dedicated to the paintings of the extreme phase of La Tour’s career, where the curators have gathered a group of paintings that, with the exception of St. John the Baptist in the Desert , which in Milan closed the exhibition by itself along with the St. Sebastian curated by Irene, were absent from the Palazzo Reale. And with respect to that occasion, moreover, the St. Sebastian curated by Irene, in Milan exhibited as an autograph for which the possibility that it might be a copy was nevertheless contemplated (in the catalog, while leaving the doubt open, Francesca Cappelletti suggested, however, that the quality of this painting “would lead one to speculate that this is the version appreciated by Louis XIII,” i.e., the original), the Jacquemart-André’s exhibition breaks any hesitation and decides to derubricate to d’aprés the painting from the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Orléans, which, however, already beforehand was among the most debated works in the Lorraine catalog.

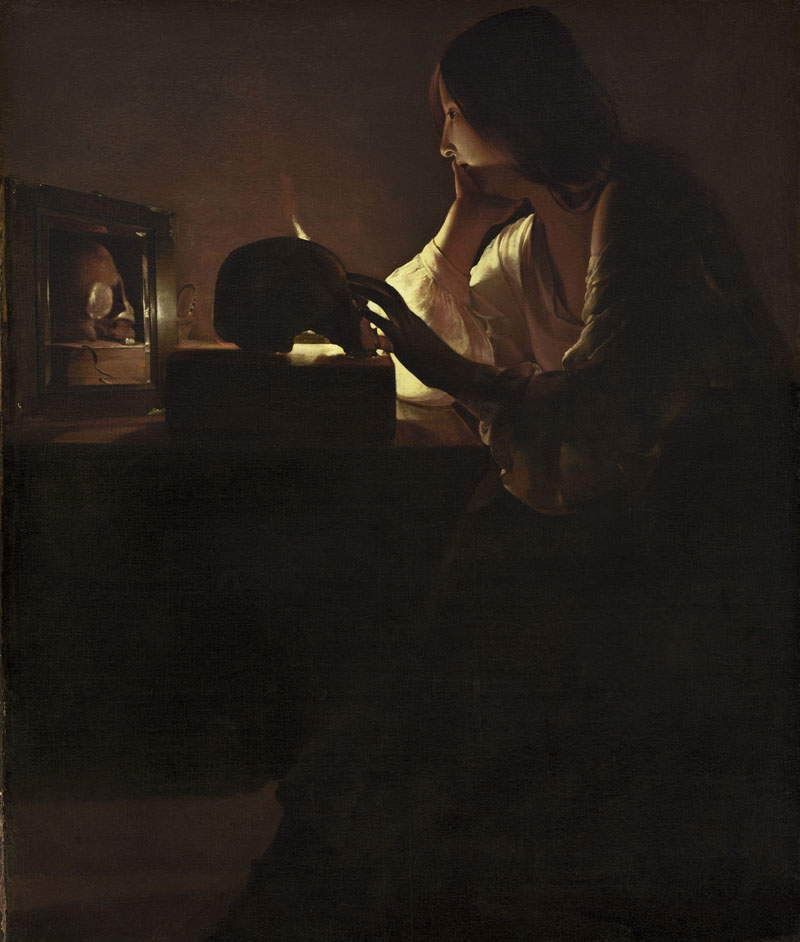

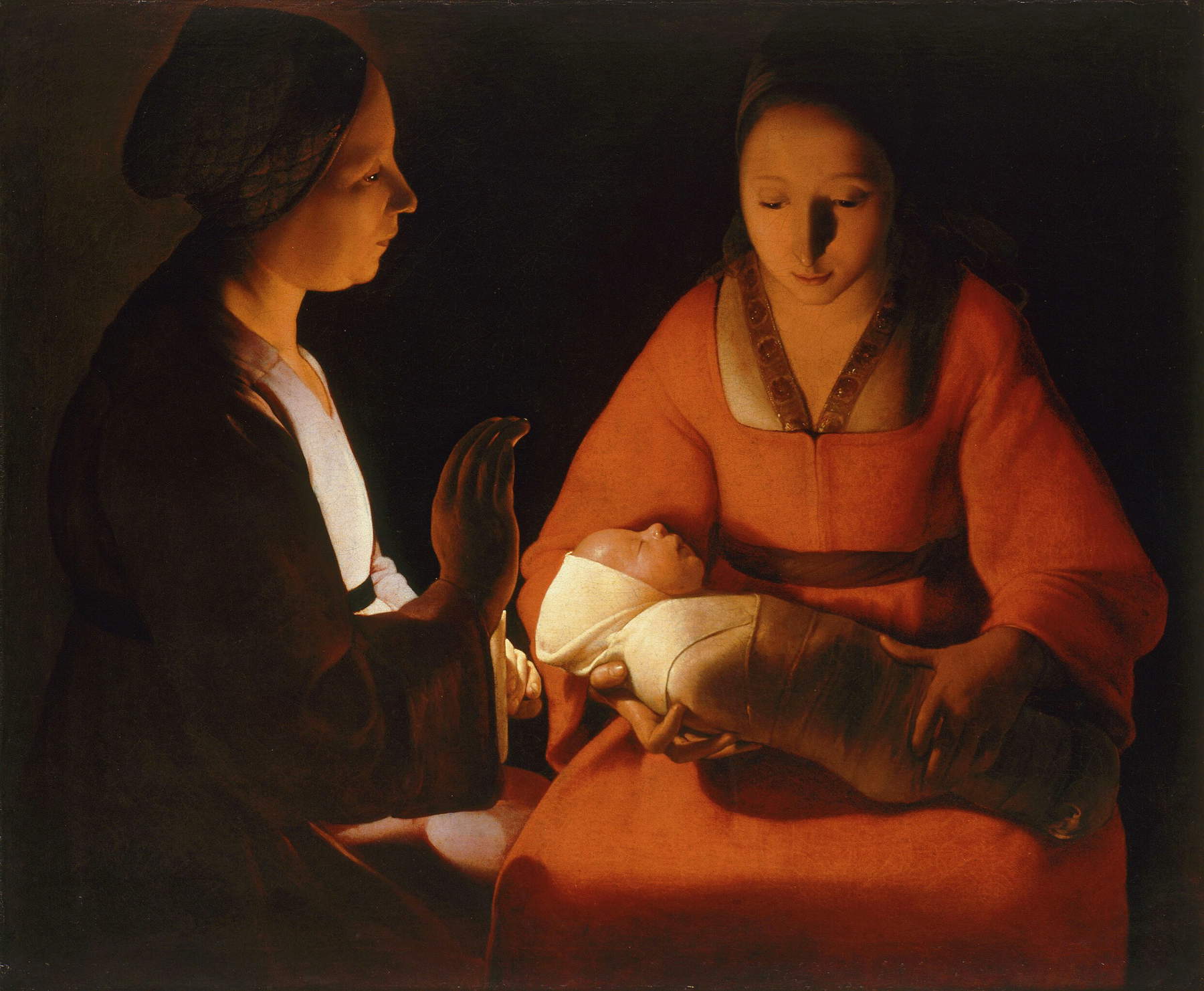

One could start precisely from the last room to list the exhibition’s novelties, starting with Fillette au brasero, the girl with the brazier that had been sold at auction by Lempertz in Cologne exactly five years ago, on December 10, 2020, for 4 million 340 thousand euros, including commission, and had set an auction record for the artist. It is not a painting that was previously unknown, since it had also been shown at the 1997 Grand Palais exhibition, but the possibility of seeing it displayed alongside the Boy Blowing a Pipe, another work of debated authenticity (at the Jacquemart-André it is presented as an original), revives the discussion about whether the two paintings originated as a pendant. The apex of the exhibition, however, is touched in the previous room, the penultimate , with the juxtaposition of the National Gallery’s Penitent Magdalene (which in Milan, by contrast, opened the exhibition: thematic divisions obviously open up the possibility of finding at the bottom what was at the beginning before) and Louis Finson’s Magdalene exemplified on the Caravaggio original. The curators’ idea is to bring out, first of all, the differences between La Tour and Caravaggio, proceeding by contrast: on the one hand, therefore, the intimacy, the recollection, the meditative attitude of the Lorraine’s Magdalene , and on the other the ecstasy, the transport, the abandonment, of Caravaggio’s, characteristics that are obviously caught in Finson’s copy as well (in the exhibition s’admires one from the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Marseille which is considered one of the oldest and among the most faithful to the original, executed when Finson and Caravaggio were in contact). Effective, in the Jacquemart-André exhibition, is the insistence on Georges de la Tour’s intellectualism, his continual reference to something else beyond a surface that is only seemingly descriptive, but in fact is so ambiguous as to make even the identification of the subjects elusive: the religious theme, in the Magdalene, seems almost to be confused with the possibility of some profane opening (the woman meditating in front of the skull and candle could easily be a personification of melancholy), and the same reasoning applies a fortiori to the Neonato at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rennes that is displayed next to it, a domestic scene with no particular connotations that could also be read as a depiction of the Madonna and Child with Saint Anne.

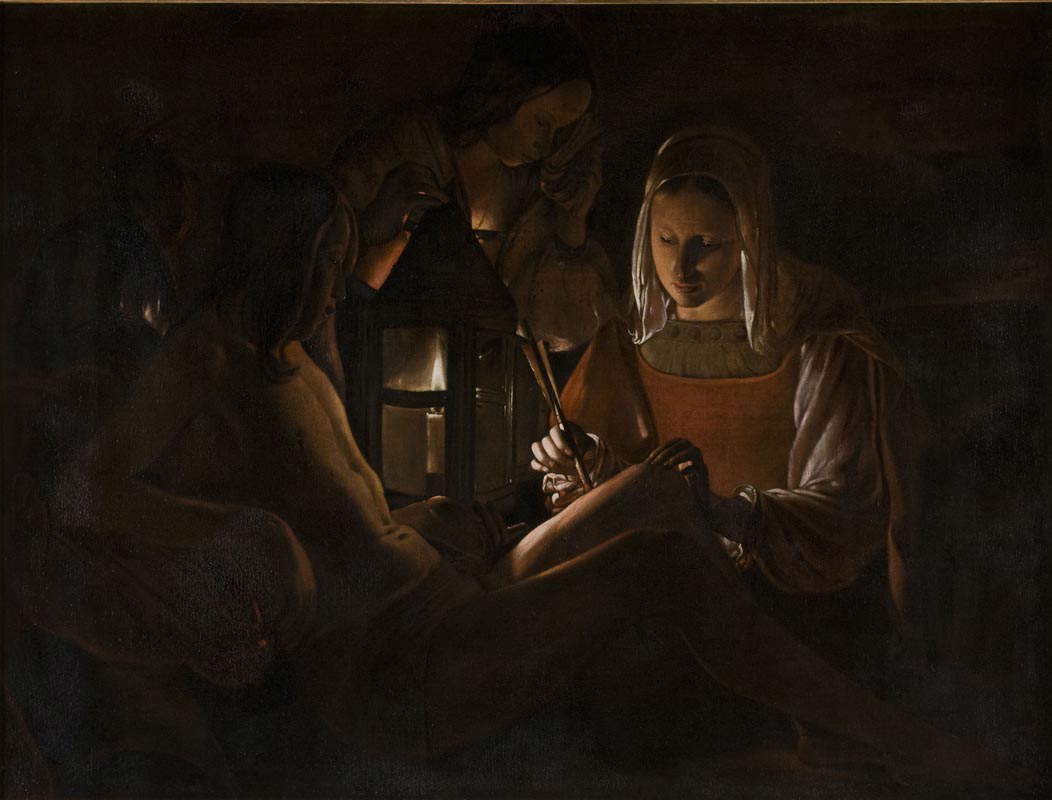

The certainly most interesting new feature of the exhibition, however, is the St. Gregory that one encounters toward the middle of the tour itinerary, in the room that gathers the apostles of the Albi cycle, a set of paintings that Georges de la Tour most likely executed in series in order to gather them around an image of Christ according to the Spanish tradition of theapostolado, a decorative complex that had its most significant precedent in the production of El Greco, of whom two complete apostolados are preserved (both in Toledo: one in the Cathedral and one in the El Greco Museum) and others that are partial or dismembered. The Saint Gregory was recently discovered by art historian Nicolas Milovanovic in the deposits of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon and has been juxtaposed with the apostles already in his catalog (the direct comparison, on the same wall, is with the St. Thomas of the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia) essentially because of the frontal setting of the subject, the pyramidal half-length figure, the pensive attitude, and certain details (the pronounced wrinkles, for example, or the folds of the sleeves). After the restoration, however, doubts about the authorship emerged: Milovanovic himself, at first almost certain of Georges de la Tour’s authorship, took a more cautious stance, since, according to him, the work would appear technically not very similar to La Tour’s known works, due to the painting being too dry, the brushstrokes not free and fluid enough, and the colors not bright enough. For these reasons, the organizers preferred to avoid taking a position either against or for: in the exhibition, the public will find the work displayed as “Georges de la Tour or copy from?”, complete with a question mark, as if the visitor should be the one to pronounce on the question. Finally, the last significant new work deserves a mention, a St. James the Greater that emerged on the market in June 2023, which went to auction at Tajan’s in Paris (it sold for 511,000 euros, starting from an estimate of 100-150,000) and is believed to be a workshop work, a copy of an otherwise unknown original and which because of the atmosphere, the way the light is treated, and the spiritual implications of the content can be compared to the Penitent Magdalene in the National Gallery. The master’s work, as mentioned, is not known to us: however, the important dimensions of this copy (one meter by almost five feet) and especially its quality stand alone as witnesses to the relevance that the St. James Major to date lost must have assumed in La Tour’s production. The painting is displayed in a section devoted to saints, called upon to account for the way La Tour explored “the possibilities of the nocturnal” and demonstrated his interest in artificial light: two versions of St. Peter’s Repentance are found here, the original at the Cleveland Museum of Art, where the saint is depicted next to the rooster in the Gospel narrative, with the suffering air of a man ravaged by remorse, and the more intimate atelier version kept at the Musée Georges de la Tour in Vic-sur-Seille. Serving as touchstones are Adam de Coster’s Negation of St. Peter to introduce the theme of the circulation in the early Parisian market of works that may have provided La Tour with inspiration in some way, and the famous St. Jerome from the Palazzo Barberini now permanently assigned to the Frenchman Trophime Bigot, called upon primarily to show how these candlelit nocturnal cogitabonds had become something of a specialty of the Nordic artists of the time to the point of going on to nurture a “science of luminous symbolism in the service of spirituality.”

Both Adam de Coster’s painting and the St. Jerome were, moreover, present at the Palazzo Reale exhibition, the difference being that in Milan the comparison was broadened to include Paulus Bor, Gerrit van Honthorst, Jan Lievens, Frans Hals, Jan van Bijlert and several other artists who offered a broader, more precise and curious contextualization than the one the public has the opportunity to appreciate at the Musée Jacquemart-André. That is, if, moreover, one is in a position to truly appreciate the path that the curators have wanted to force almost by force into the rooms devoted to temporary exhibitions, which are totally unsuitable for major exhibitions, because they are cramped, because they have been crammed almost to their physical limits, often with more than questionable design solutions (paintings practically attached to the doors, various jumblings, and then terrifying the’setting up of the room dedicated to the diffusion in Lorraine of humble subjects, arranged in a small corridor that connects two other rooms, and where there is, moreover, a drawing of a Repentance of Saint Peter that has been attributed to La Tour and in the case could be a milestone of supreme importance, since there are no certain drawings of him to date), and because Georges de la Tour, it seems, is an artist quite beloved by the French, who are storming the Jacquemart-André exhibition en masse, with the result that the rooms are crowded often beyond tolerability and it becomes difficult to visit the exhibition concentrated. Poor Georges de la Tour did not deserve to drown inside such a suffocating, disastrous set-up.

Those who experienced the crush of the past Caravaggio exhibition at Palazzo Barberini and want to find similar sensations again, can pass the turnstile separating the permanent collection from the temporary exhibition rooms and jump into the fray. On the other hand, those who believe that an exhibition needs spaces that do not force visitors to elbow their neighbors every time they turn around to see another painting or that avoid theinconvenience of having to go through gymkhana between rooms to avoid the photographic sets of other visitors who improvise selfies, self-shots, company shots, and solo shots, then he will have to wait for the day when it is realized that small space should correspond to small exhibition, or he will have to resign himself to struggling in the welter.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.