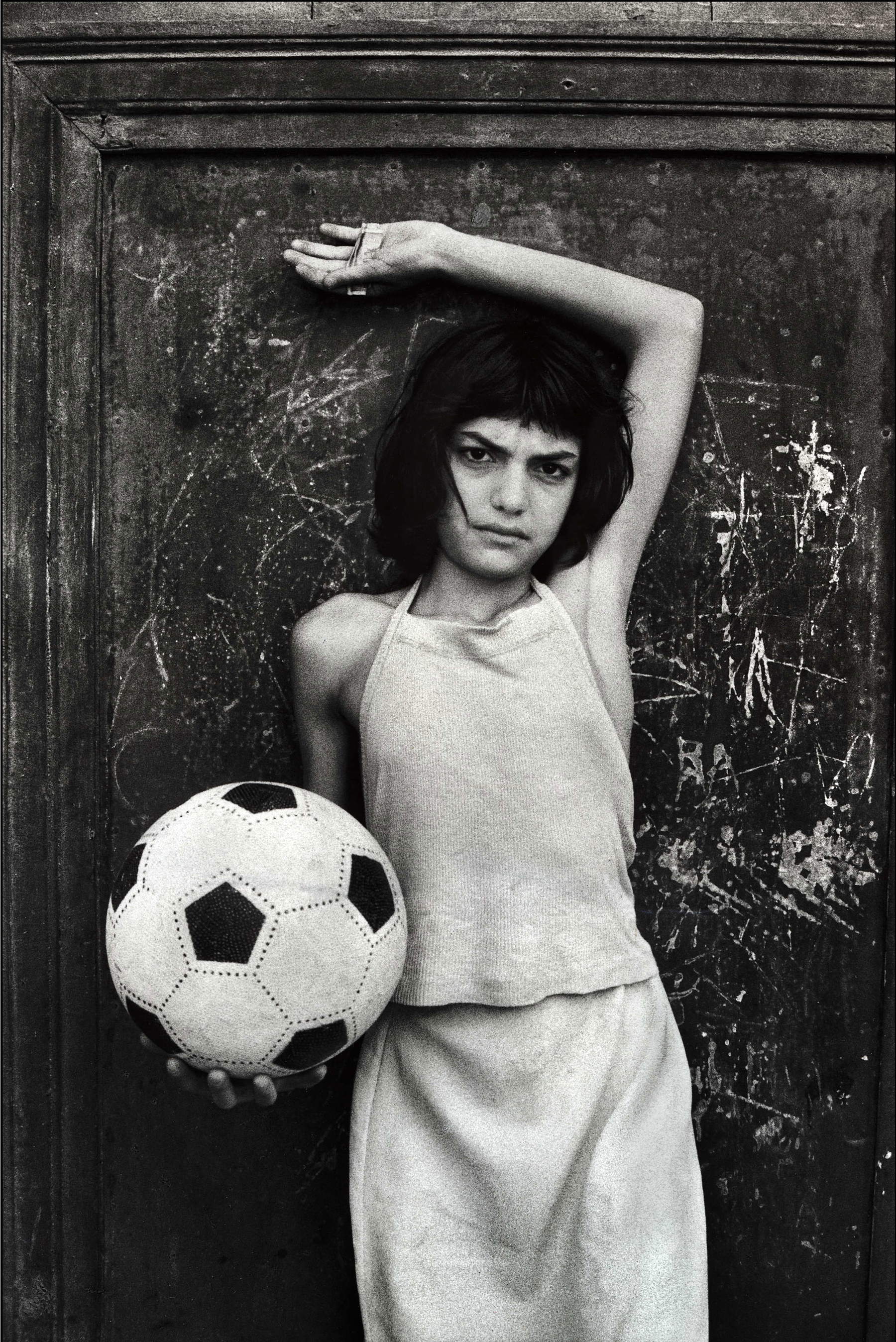

Certain documentary-style shots, besides standing out in isolation in the teeming iconographic firmament of recent reportage history for the eloquence of a phenomenon effectively risen to noumenon, are candidates to become staples of photography tout-court when the passage of years and the incessant multiplication of images, instead of diminishing their relevance, confirms them indelible in memory. Some of them, such as Nilufer Demir’s 2015 one that captures the lifeless little body of Alan Kurdi, a Syrian refugee just three years old found lying on his stomach, as if sleeping, on the beach in Bodrum after the shipwreck, embody with the utmost intensity the medium’s aptitude for capturing the unbearable moment when consciousness is naked before the evidence of the unspeakable. Others, such as the Afghan Girl, a portrait taken in a refugee camp in Pakistan in 1985 by Steve McCurry of 12-year-old Sharbat Gula, whose tragically grainy gaze has become a universal emblem of the irreducible catastrophe of war, give an account of photography’s ability to sublimate and condense a knot of issues into a striking snapshot. Another shot that could be added to this pantheon of absolute images of the twentieth century is Quartiere Cala. The Girl with the Ball, in which Letizia Battaglia in 1980 poses a teenager from Palermo’s working-class neighborhoods against a doorway scratched by wear and tear, focusing on her magnetic expression as an adult and the claim to independent subjectivity implicit in her proud appropriation of a traditionally male sport.

The retrospective Letizia Battaglia. L’opera: 1970-2020, hosted for the first time in Italy at the Museo Civico San Domenico in Forlì after French presentations at the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris and at the last edition of the international festival Les Rencontres d’Arles, provides a valuable opportunity to delve into an artistic and biographical path that is still little appreciated despite its importance and entirely unique with respect to the conventions that usually govern artistic careers. Battaglia was born in 1935 in Palermo, married at the age of sixteen and became the mother of three daughters during a marriage she experienced as a renunciation of all intellectual and personal autonomy. She did not begin photographing until she was thirty-four years old after separating from her husband, working as a reporter for newspapers and magazines, at a stage of existence when most women photographers of her generation would have already consolidated a mature language. The exhibition curated in Forlì by Walter Guadagnini, artistic director of Camera - Centro Italiano per la Fotografia in Turin, in collaboration with the Jeu de Paume museum, reconstructs with philological precision the evolution of this powerful voice of Italian photography by retracing fifty years of tireless activity, whose aesthetic, ethical and emotional coherence is highlighted. As can be seen from the more than two hundred shots in the exhibition, photographing for Battaglia is a necessary gesture of self-appropriation, a way of existing in the world as an autonomous, acting gaze, capable of determining its own relationship of co-participation with reality.

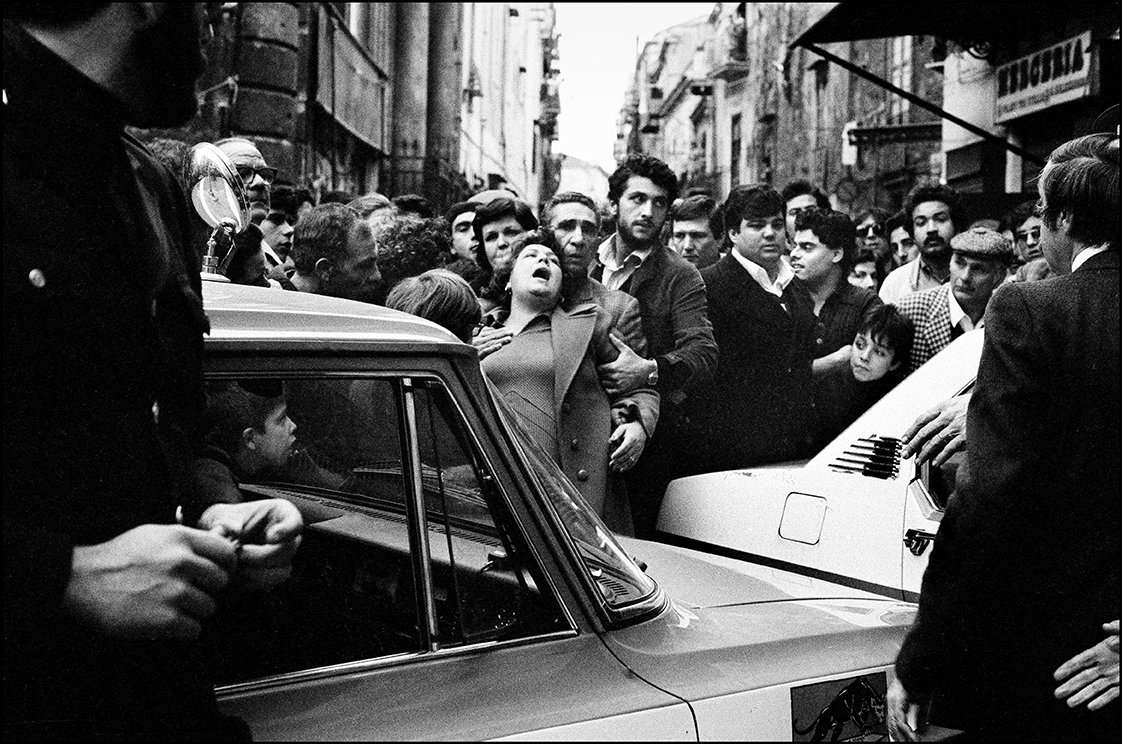

The exhibition opens with images from her early days, set in Milan where the artist had moved after her separation: these are photographs for popular magazines of topless girls and showbiz personalities that reveal a photographic practice already sensitive, especially to the female condition, but still searching for its own syntax. These images, rarely exhibited and partly unpublished, hint at the rapid refinement of a self-taught photographer learning the craft as if it were an initiation, moving toward an increasingly intimate relationship with the camera and the subject. When Battaglia returned to Palermo and began his collaboration with the daily newspaper “L’Ora,” his photographic language became incandescent testimony: the shots dedicated to Mafia murders, the funerals of murdered judges, trials and moments of collective mourning that marked the city between the 1970s and 1990s constitute the most powerful nucleus of his production and the interpretative key to his entire photographic research. Consider, for example, the image of Piersanti Mattarella, president of the Sicilian Region assassinated on Epiphany Day 1980, his bloodied body surrounded by men in uniform, his brother Sergio holding him up in an embrace in which, in addition to the tragedy of political and human loss, centuries of Pieta and sculptural Depositions in art history echo. Battaglia, in the many interviews he has given, recounts that he photographed that scene almost by accident, stopping out of pure professional instinct with a colleague in front of a huddle of people gathered around a car riddled with gunshots, not knowing who the victim was and thinking it was a traffic accident. Yet, that photograph becomes a symbol of Mafia violence, of the relentless lust of the familiar gangs to eliminate anyone who tries to change things. Or consider the handcuffed portrait of Leoluca Bagarella, a Mafia boss framed with almost unbearable proximity: Battaglia recounts using the wide-angle lens instead of the telephoto lens, getting close enough to be kicked by the enraged criminal, but only after capturing him in his image-cage. The rejection of the distance that the telephoto lens would allow is for her an ethical principle even before a formal choice. Unlike the colder, almost clinical sensibility of certain coeval international photojournalism - think of James Nachtwey’s critical detachment or Sebastião Salgado’s images of suffering sublimated by beauty - Battaglia maintains such a bodily contiguity with his account of society’s vulnerable margins that the tone is never descriptive-sociological, but rather visceral, immanent, as if he cannot afford distance as a presupposition of objectivity.

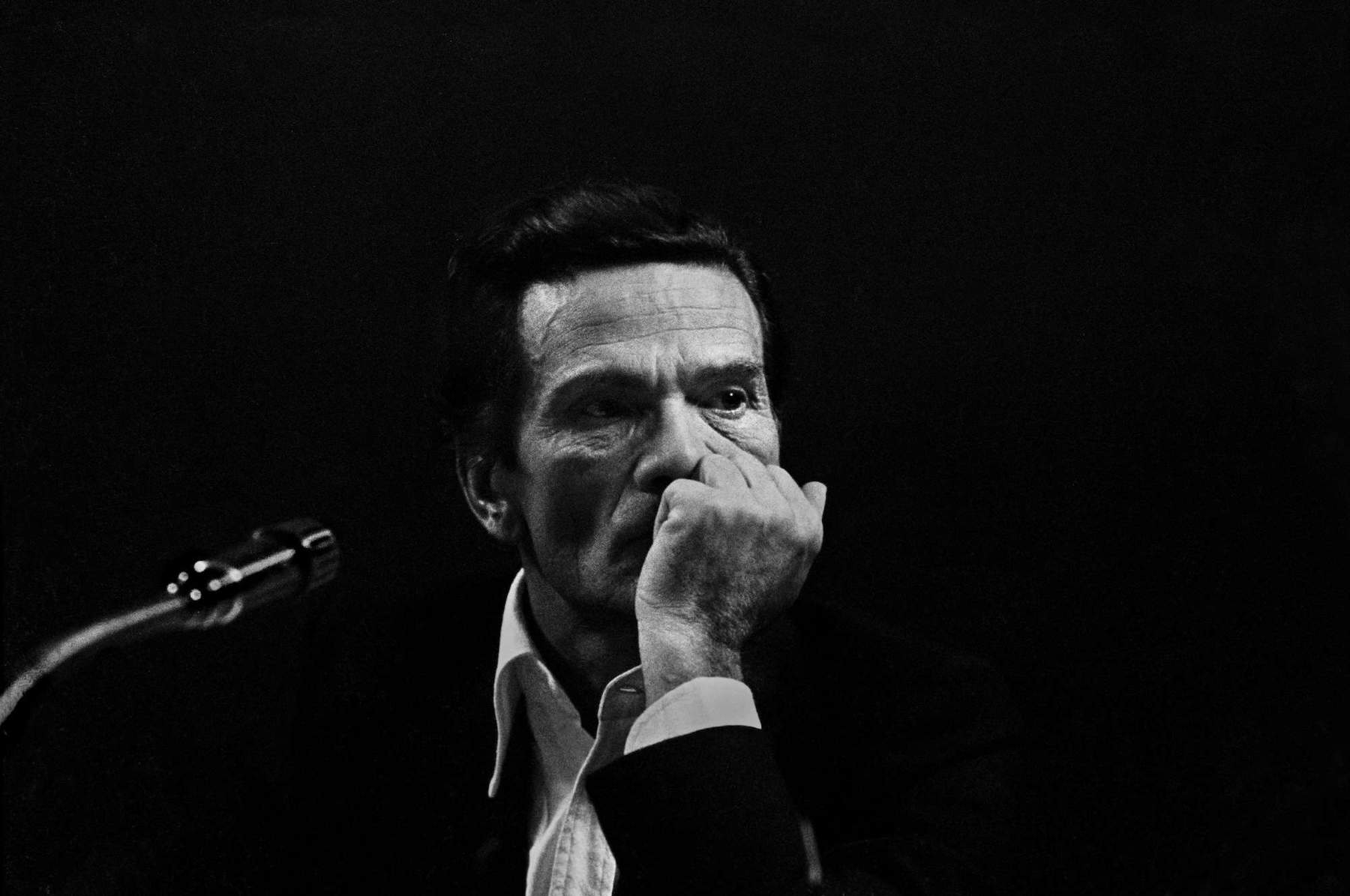

The strict black and white, the deliberate absence of color that might dilute the traumatic fact depicted by making it pictorial, decisively reiterates the rejection of visual consolation. The sequences devoted to the blood events and the sometimes paroxysmal, sometimes internalized despair of the victims’ relatives bring out a dramaturgy of testimony that transcends pure documentary value. Through Battaglia’s lens, these representatives of legality and civil resistance seem to transfigure themselves into timeless tragic figures, though without any artificial concession to composition. The hand of Cesare Terranova, a member of the Anti-Mafia Parliamentary Commission killed in 1979 in an ambush, leaning on the seat of his car, “very sweet,” as the photographer recalls; Judge Giovanni Falcone at the funeral of General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa in 1982, his face marked by the awareness of a future doomed to death; Giorgio Boris Giuliano, head of the Squadra Mobile, photographed at the scene of a murder in Piazza del Carmine, where a woman faints unable to sustain the macabre spectacle: each image has a punctum that universalizes its scope. His photographs, even decades later, remain active, disturbing and urgent in questioning the present because they plunge straight to the heart of pain, captured in its disharmony, its brutality, without mediation of an aesthetic order.

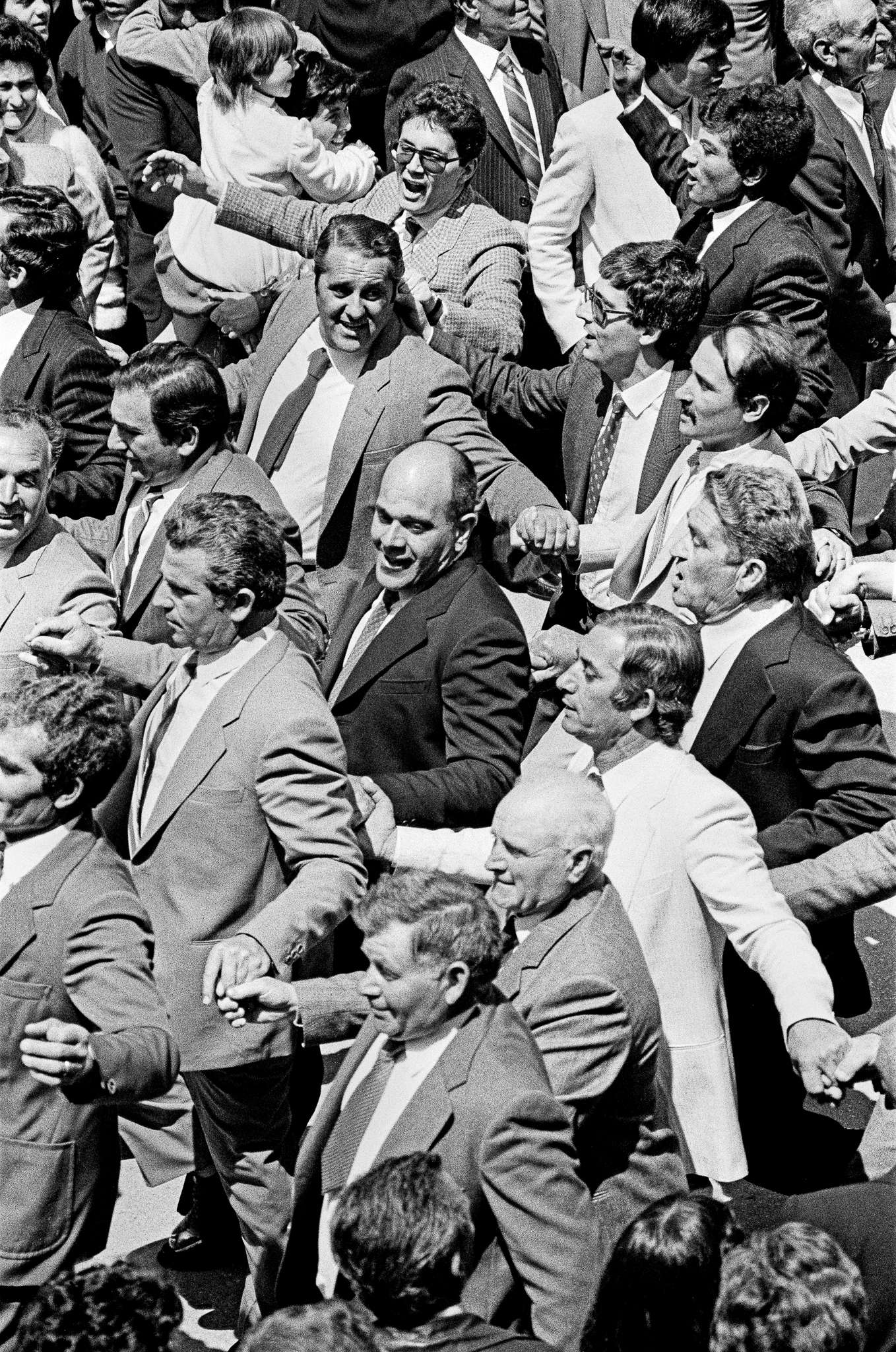

From the sequences dedicated to youth political mobilizations in the squares, to religious processions, to family celebrations where women and children immortalized in moments of tenderness prevail, one can sense another fundamental aspect of her research: the gift of delicately penetrating the event to capture the crucial moment, the frame in which gesture, emotion and a few environmental details converge to build a world. Battaglia’s ability to immerse himself in the social fabric he documents cancels the separation between observer and observed: this is not ethnographic reportage on Sicilian popular culture, but empathetic participation, emotional involvement with the subjects portrayed. Not only, then, the need to document the violence, blood and death that raged in Palermo during the bloodiest years of the Mafia war, but the equally urgent need to restore visual dignity to that same city through the celebration of its dogged vitality. In the dialectic between these two Palermo, that of crime news and that of everyday life, is rooted the peculiarity of Battaglia’s gaze, which has always rejected the definition of “photographer of the Mafia,” claiming that the Mafia was only one of the components, however tragically pervasive, of the reality she documented. As she herself states in the film testimony accompanying the exhibition, she sought life, not death. She was looking for resistance, not surrender, and she found it in the eyes of the little girls she met on the street, future women already marked by the harshness of life in whose fate she empathizes, transforming reportage into a vulnerable act of mutual recognition.

The issue of gender is inescapable for understanding her work: the only woman photojournalist in the newsroom, forced every day to fight to be admitted to crime scenes to carry out her craft, Battaglia transformed her oblique position in relation to the male power system, as much criminal as institutional, into a creative resource. At the scenes of the murders, as she herself recounts, it was all men: the killers, the victims, the policemen, the medical examiners, but it was precisely her femininity that helped generate her integral gaze, capable of capturing aspects that a male eye would probably have overlooked, such as the anguish of widows and mothers who lost their children, the silent suffering of those relegated to the margins of the public scene and can only mourn. Similarly, the photographs taken in the Real Casa dei Matti, the psychiatric institution in Palermo, where Battaglia led theater workshops as part of an increasingly totalizing civic and cultural commitment, testify to his empathy with the most defenseless and marginalized subjects, sustained by the imperative to visually compensate those people deprived of their social voice. The faces that emerge from the background, sculpted by a light that accentuates their sculptural and theatrical plasticity, possess a quality of presence that transcends their condition as internees: they are faces that look, that question, that claim their right to be seen. In this process of restoring subjectivity through the image, his conception of photography as a committed form of relationship between the viewer and the viewed is fully manifested.

A decisive watershed in his career took place in 1992: after a little more than twenty years of continuous professional activity as a photojournalist, following the Capaci and Via D’Amelio massacres in which Judges Falcone and Borsellino lost their lives along with their escorts, he decided to discontinue the photographic narrative of the mafia phenomenon. The violence is too pervasive, overwhelming. The photographer, as she declares in the documentary that accompanies the exhibition, is horrified at no longer remembering which had been the first dead person framed by her lens and realizes that her psychological equilibrium cannot bear the confrontation with horror any longer. He renounces documenting, therefore, the two massacres that mark the end of an era, amid the simultaneous emergence of doubt that the obsessive repetition of images of death risked normalizing violence rather than denouncing it. From that moment on, his photography moves toward a more meditative and intimate dimension, while holding firm to its affective vocation to relationship. The geography of her work expands around the world-Egypt, Turkey, Russia, Iceland-where the relationship between photographer and subject, in moving away from Sicilian political history, takes on characters less dense with moral implications. In these international reportages we find the same immediacy that characterizes the Palermo photographs, but with a more pronounced diaristic component, as if traveling represented a way for Battaglia to verify the universality of her gaze by testing it on different cultural contexts. The themes dearest to her return: women’s faces, children, conditions of economic precariousness faced with dignity, expressions that reveal more than words can say.

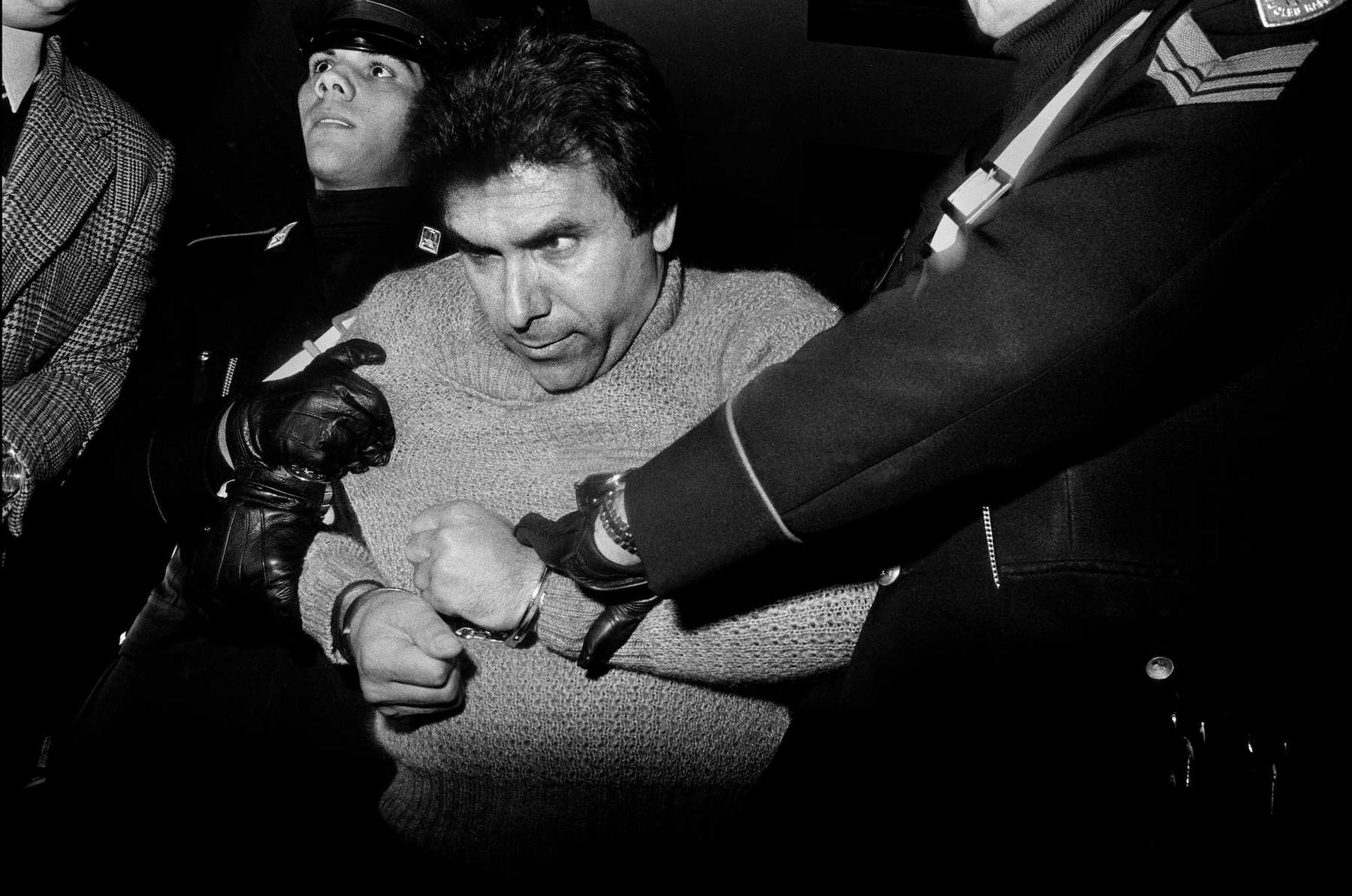

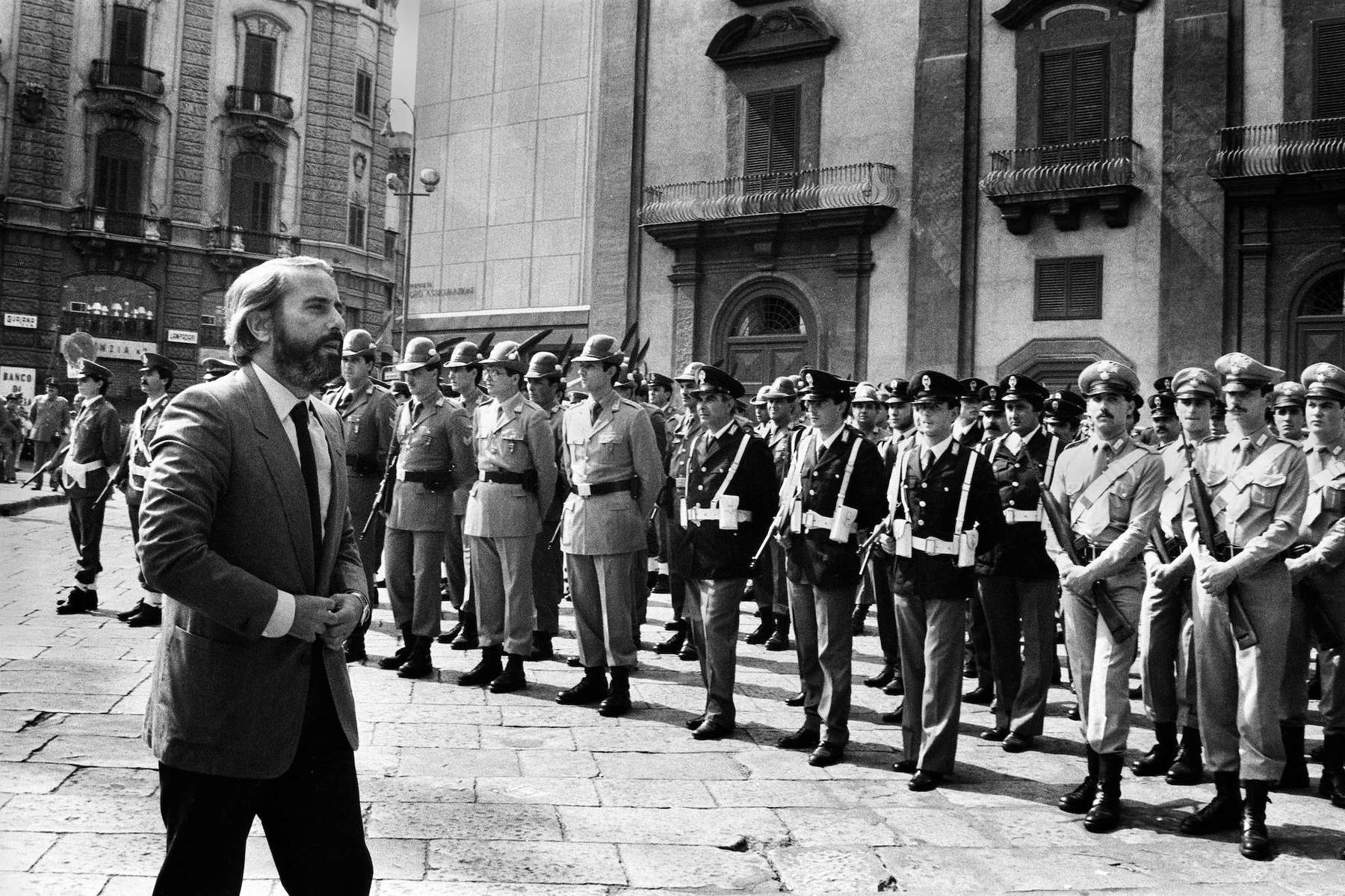

At the same time, she became personally involved in building a cultural alternative to her Palermo still at the mercy of the Mafia and the silent complicity of the institutions, which had meanwhile reorganized in different and more subterranean ways. The last two decades of her life, until her death in 2022, are mainly dedicated to the International Center of Photography at the Cantieri Zisa, a project that began in 2012 and came to official fruition in 2017, and to the founding of the Letizia Battaglia Archive, now run by her grandchildren, intended to preserve, study and disseminate her work. In her very last years, Battaglia also resumes photographing her beloved city, returning to the main themes of her research with a gaze transformed by time and wisdom. He recovers some of the most dramatic photographs of his career as a reporter in a retrospective and experimental key: printed in a very large format, they become the backdrops of other shots that are superimposed on them, generating new images in which the nerve center is shifted from the representation of death to the scream of denunciation. In this process of visual and emotional reworking lies the extreme attempt to metabolize trauma through aesthetic transformation and to find an (impossible) form of pacification with a past that continues to torment her.

The exhibition in Forlì thus represents the first Italian moment of the hoped-for international consecration of a complex intellectual figure, a spokesperson for a photography acted as an instrument of civil resistance, a refusal of indifference and a struggle for the visibility of those whom violence would like to erase. The fact that this retrospective arrives in Italy only after having been launched abroad says, finally, something significant about our country’s difficulty in dealing with its most uncomfortable testimonies, and precisely for this reason, fifty years later, those shots that documented some of the darkest pages of Italian history retain intact their capacity to wound, forcing us to the awareness that looking always entails an inescapable responsibility.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.