One senses a vaguely familiar atmosphere upon entering the Italian Pavilion through the back door and finding oneself immersed in the forest of innocent pipes with which Massimo Bartolini, who has been entrusted with our national participation in this year’s Biennale, has filled the second Brim of the pavilion. One has the feeling of having seen a similar installation before. A labyrinth of tubes, an architecture of tubes. One wonders where. Then, reasoning for a moment, comes the answer: at the Fuorisalone! In Milan, two years ago. And not in some secondary venue , but in the courtyard of the Statale, one of the focal points of the Fuorisalone: the architect and designer Piero Lissoni had designed, commissioned by Sanlorenzo, an installation called Doppia presenza, a large scaffolding of innocent pipes into which one could enter, walk, always wrapped in the construction material also dear to Massimo Bartolini. “It’s as if we had transported to the State University courtyard a piece of the construction site, the place where boats are built,” the architect explained. Bartolini, less prosaically, has not transported pieces of the shipyard to Venice, and of course it would be excessive, ungenerous and mean-spirited to demote his effort to a mere manifestation of architectural-building impetus, but perhaps we could stick to thinking, meanwhile, that the’artist designated to represent Italy at the Biennale has transported to the lagoon a kind of monumental re-government of a work already presented elsewhere and imagined for far more congruous spaces, and then that this dimension befits little the poetry of his art.

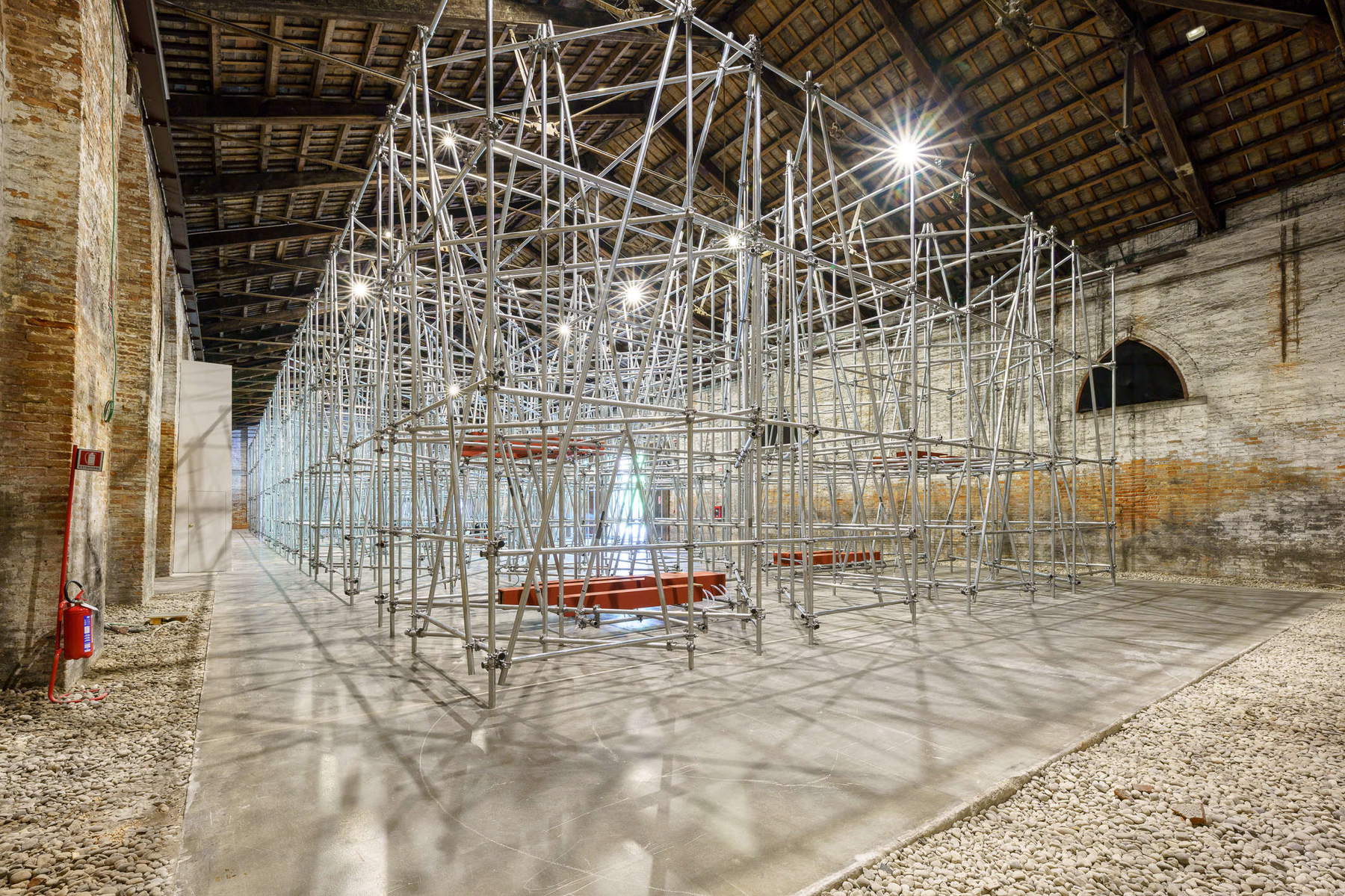

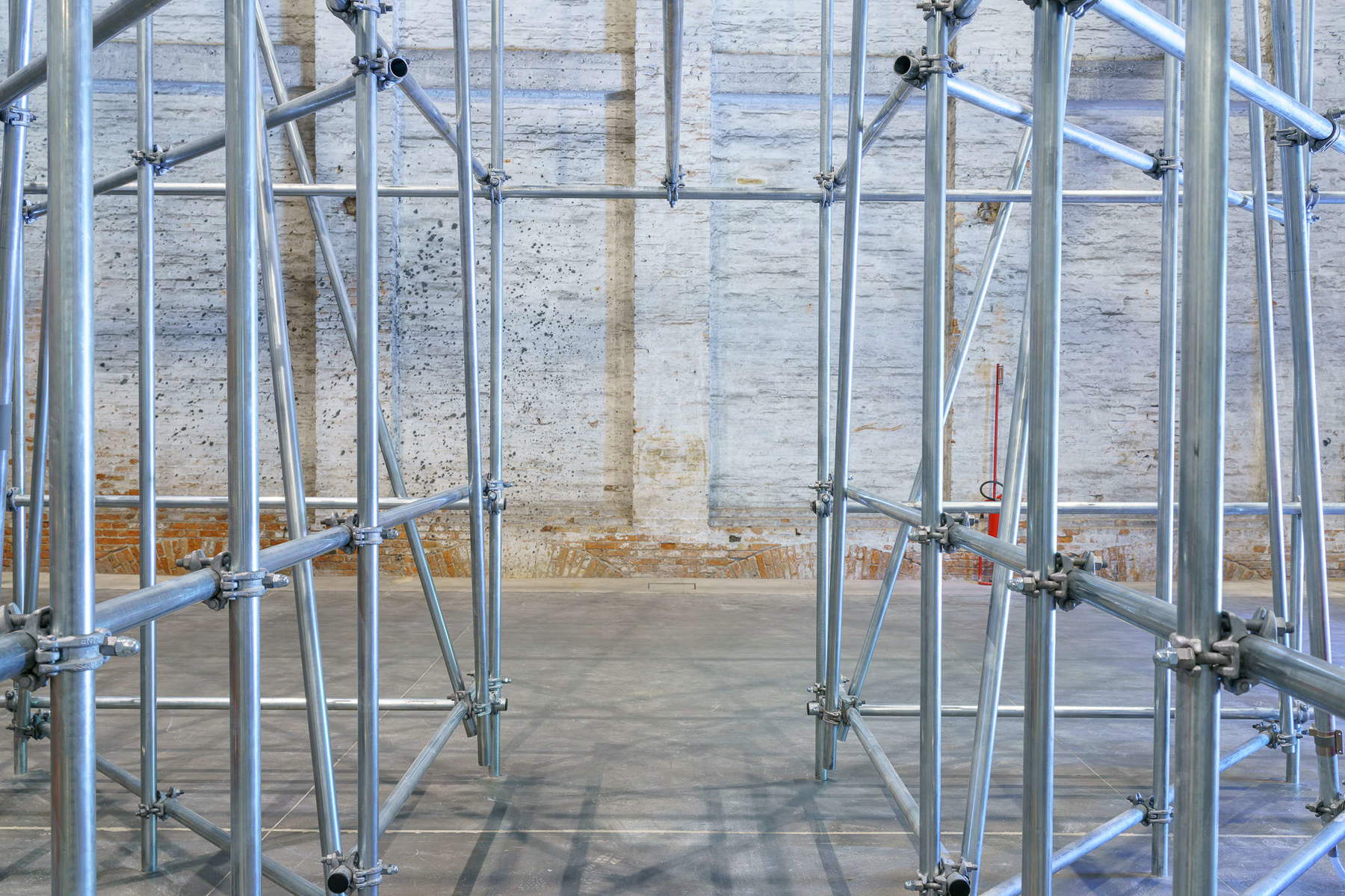

At the Biennale, Bartolini addresses a colossal “invitation to listen” to the public, which takes the form of the project Due qui / To hear (the name in Italian is a literal translation of the English Two here, which to curator Luca Cerizza reminds him by assonance of the verb To hear, " to listen“) and which is substantiated in an exhibition divided into three moments, with a circular progression: everyone can enter the Italian Pavilion from wherever they like, choosing either the pavilion’s usual entrance, the one facing the Gaggiandre, or the back door, which faces the Garden. If one chooses the front door, one enters the first Tesa, where one will find a long parallelepiped (a ”column resting on the ground," according to the official narrative) with, lying on its end, a statuette depicting a Bodhisattva, a living being who aspires to enlightenment and has vowed to help other living beings attain it as well. The reclining column, as is typical in Bartolini’s installations, is actually a musical instrument that emits, in this case, a low sound. The second Tesa, accessible from the door to the Garden or by passing through the first Tesa, reveals itself to the visitor with the imposing scaffold that is actually an organ through which an electronic sound carpet composed by two young musicians, Caterina Barbieri from Italy and Kali Malone from the United States, spreads through the Pavilion. Instead, in the center of the installation here is the sculpture Conveyance, a wave that rises and falls continuously within a stainless steel circle. Finally, the experience continues in the Garden, which hosts the third moment of Due qui / To hear: among the trees resounds the music composed by Gavin Bryars and Yuri Bryars, A veces ya no puedo moverme, inspired by a text by the Argentine poet Roberto Juarroz about a human being who perceives himself as a tree, connected to the rest of the world with his roots.

Bartolini and Cerizza’s exhibition, in addition to being one of the best to be seen at the Italian Pavilion in recent years, is certainly a refined project, supported by solid philosophical foundations (Cerizza quotes Byung-Chul Han, among others: “In stretching out the ear, which is a form of inaction, the self, presupposed of differentiations and delimitations, is silent; the self that stretches out the ear immerses itself in the whole, in the unlimited, in the infinite”), and above all profoundly political: there is perhaps no activity more political than listening. Simone Weil was convinced that listening was the fundamental basis of commitment to one’s neighbor, that attention was the real engine of all moral action: “Every being,” she wrote in her Cahiers, “cries out in silence to be read otherwise. Do not be deaf to these cries.” And that is essentially what Cerizza is probably convinced of as well, at least where he explains in his introduction to the Pavilion that “the title of the project suggests how hearing, and even better listening, is a form of attention to the other.” A slight digression may be useful at this point: anyone who followed the Biennale in its opening hours (or anyone who opened a news program in those days sufficiently nostalgic to devote a minute of coverage to the Venice Biennale in an era when the Venice Biennale matters less to the news than thelatest single by Annalisa) could not help but delight in the performance of the mayor of Venice, Luigi Brugnaro, who lavished himself, with calculated nonchalance, on a kind of real-time critique of the project (“I didn’t like the Italian Pavilion. And I say this: the more art is discussed, the better. The artist before got angry, said I offended everyone. But I am for the figurative. At Ca’ Pesaro we have a Klimt who was at the Biennale, and I hope that the figurative, painting, photography can come back here too.”). As crude as we want, as crude as we want, as irritating as we want to say, so much so that the usual and homologated turba of theart world, unfailingly gathered at the inauguration, after accepting Bartolini’s invitation to listen, wanted to show that they had grasped the concept by submerging the first citizen’s irritating speech with whistles. Of course, indignation towards the mayor is the most immediate and also the easiest response, yet Brugnaro’s remarks are worthy of attention that goes a little beyond the markings of the territory in which the indignados of contemporary art performed. And not only because we are dealing with a politician who commented on a deeply political exhibition: they are deserving of attention above all because they are the clearest demonstration of the limitations of the project. It is not a question of taste (“I did not like it”), for taste should not be an element capable of determining a critical judgment: the question concerns, if anything, the response of a hypothetical visitor to this year’s Italian Pavilion.

It is quite evident that Bartolini’s work did not reach Brugnaro: is it because of the mayor’s jerkiness or because perhaps the project is not quite measured to its host site, because it is not immediate, because it is complicated? Without going into the merits of each person’s personal sensibility (there are those who can remain indifferent even when entering the Sistine Chapel and would not for this reason be a less respectable person than those who, on the other hand, in front of Michelangelo’s frescoes are likely to fall into a swoon), and also believing it completely senseless to hope for a return to figurative instead of Bartolini’s conceptual with theidea that a so-called “traditional” figurative better represents Italy (from the 1960s onward, our country has written the most important pages of world art history almost exclusively with non-figurative artists), there is meanwhile to think about where the Italian Pavilion is positioned. The public typically arrives there after visiting the entire international exhibition at the Arsenale and after passing all the pavilions it encounters in succession (except the last one, that of China): an experience that is usually quite chaotic and exhausting, due to the amount of other visitors one encounters, the amount of information one is subjected to, and the constant switching of languages from one exhibition to the next that forces the brain to constantly switch between different settings. Bartolini’s Zen work requires concentration: who can keep fresh after two or three hours in the midst of the chaos of the Venice Biennale, sufficiently to be able to grasp an invitation that presupposes the assumption of a demeanor, if not meditative, at least absorbed? Certainly: it is clear that any exhibition, by any artist, requires a minimum of concentration, so the assumption might seem specious, but it is equally clear that there are works that can reach the public with more immediacy and thus place the visitor in better and more comfortable conditions to open up to the artist’s project. Tosatti’s Italian Pavilion, for example, while definitely weaker and less solid than Bartolini’s, was much more engaging because it was able to speak to the audience in a more direct language. An example: if I arrive at a hotel in the evening tired after a trip and turn on the television, it will be more comfortable for me to follow a program that is less interesting but where the presenter speaks in Italian than to tune in to a program of higher quality but where the presenter speaks in a language in which I am much less fluent: it requires me to have a greater amount of concentration, and after a trip I may not be able to maintain it, so I may not necessarily get what the presenter intends to communicate to me. On the contrary, if I watch the same program in a foreign language the next morning, fresher and more lucid, I will be able to appreciate it better.

This is then why Massimo Bartolini’s work rendered better in the spaces of the Centro Pecci: Due qui / To hear is nothing but a kind of sequel to Hagoromo, the exhibition that Bartolini and Cerizza had presented in Prato two years ago. Artist and curator, of course, can repeat endlessly that this is a different project (and it is true), but there is not a single component that is really new. The Bodhisattva is a recurring figure in Bartolini’s art (the reclining column is not, but without the Bodhisattva we probably would have mistaken it for a Giovanni Anselmo piece, and the Bodhisattva without his musical instrument would have catapulted us into a 1970s Biennale). Conveyance is a work that is already some 20 years old. Innocent pipes have been recurring in Bartolini’s practice for at least fifteen years in a kind of constant reissue of the same work, with ups and downs. In Prato, for example, the ensemble gave different suggestions: in the solitude of the Pecci’s halls, the hypnotic movement of Conveyance was an excellent introduction to In là, a snake of innocent pipes winding its way through five halls, traversing them and making Bryars’ notes resonate in an environment that’was undoubtedly capable of fostering the attitude necessary to grasp the atmosphere of suspension that the installation set out to suggest (not to mention the fact that one went there on purpose, and did not arrive after twenty other exhibitions). And In là in turn was the continuation of Organi, an installation placed against a wall, which was observed in a, shall we say, traditional way. Identical means, different intent, different environment: if Hagoromo was a well-constructed anthological exhibition, lyrical and strong with a flashy but not invasive installation that acted as a frame, Due qui / To hear appears instead as a leap into a dimension not very appropriate to the elements that compose it and not very suitable to spread that poetry that should hover around the meanings that are hidden behind the forms (the circularity of time, the idea of music as a fluid movement uniting people, listening as self-improvement, but like to think of it as an open work that also communicates a sense of instability). And in this regard, perhaps it would be useful to ask whether it is still useful to entrust the Italian Pavilion to a single artist, and not only because it might be extremely reductive to choose a single person to represent the entire art scene of’a country such as ours (assuming that this is how one wants to understand our national participation in the Venice Biennale), but also because so far neither of the only two monographic projects for the Italian Pavilion has seemed to stand up to the enormous space of the Tese delle Vergini.

Space and location, in short, struggle to foster the experience that Due qui / To hear would like to activate. Conveyance is placed in the middle of the project’s eponymous installation and should be a kind of pulsating heart, the centerpiece of the exhibition, but it seems almost taken and placed in the middle of the second Tesa without real necessity (because the center of the installation, the one “from which one can best hear,” the curator informs us, is chosen as the place to install a sculpture that “also serves as a seat around which more people can meet?” Then what is to be done? Is one to listen or talk?). And then, the installation of innocent pipes that in Prato was the “backbone” of the exhibition, as stated in the illustrative material, in Venice becomes one of the two areas where the visitor’s experience should be activated. Doesn’t this abrupt change of use, we might say, of a work that has remained essentially true to itself over the years (“it is the largest example conceived so far of a series of installations that Bartolini has designed in recent years,” the curator tells us), risk making the work of an artist who over the years has always shown himself to be decidedly changeable even more elusive? And if a work previously at risk of trespassing into design and architecture, and yet capable of holding up as a “backbone,” now becomes one of the two centers, why, one might ask somewhat provocatively, should a visitor go to the trouble of visiting the Venice Biennale when all he or she needs to do is stop by the Fuorisalone? The problem is certainly not the medium: if we assume that both Canova’s Hebe and the statues of Padre Pio being sold in San Giovanni Rotondo are plaster sculptures, we must likewise assume that with innocent pipes one can create as much a work of art as a common construction scaffold. The problem is attitude: when one approaches architecture or design (and, in this respect, this Biennale has seen worse: just take a tour of the nearby pavilions of Argentina and South Africa) why should one waste time visiting the Art Biennale?

Finally, it is necessary to ask the question of the topicality of Massimo Bartolini’s language. Putting it mildly: it will not necessarily get better in the future. Given the current times, we run the risk of finding ourselves a rappel à l’ordre Italian Pavilion 2026 chock-full of tardy hyperrealists or bumptious revancers of the classic that will make us rethink Bartolini’s exhibition with nostalgia. However, this does not mean that we should not ask ourselves whether this conceptual is still in tune with our times, still representative of the impulses that agitate the art scene in our country, still useful to speak to an audience that is not composed exclusively of insiders, who at the moment seem to be the only ones interested in expressing themselves on Due qui / To hear.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.