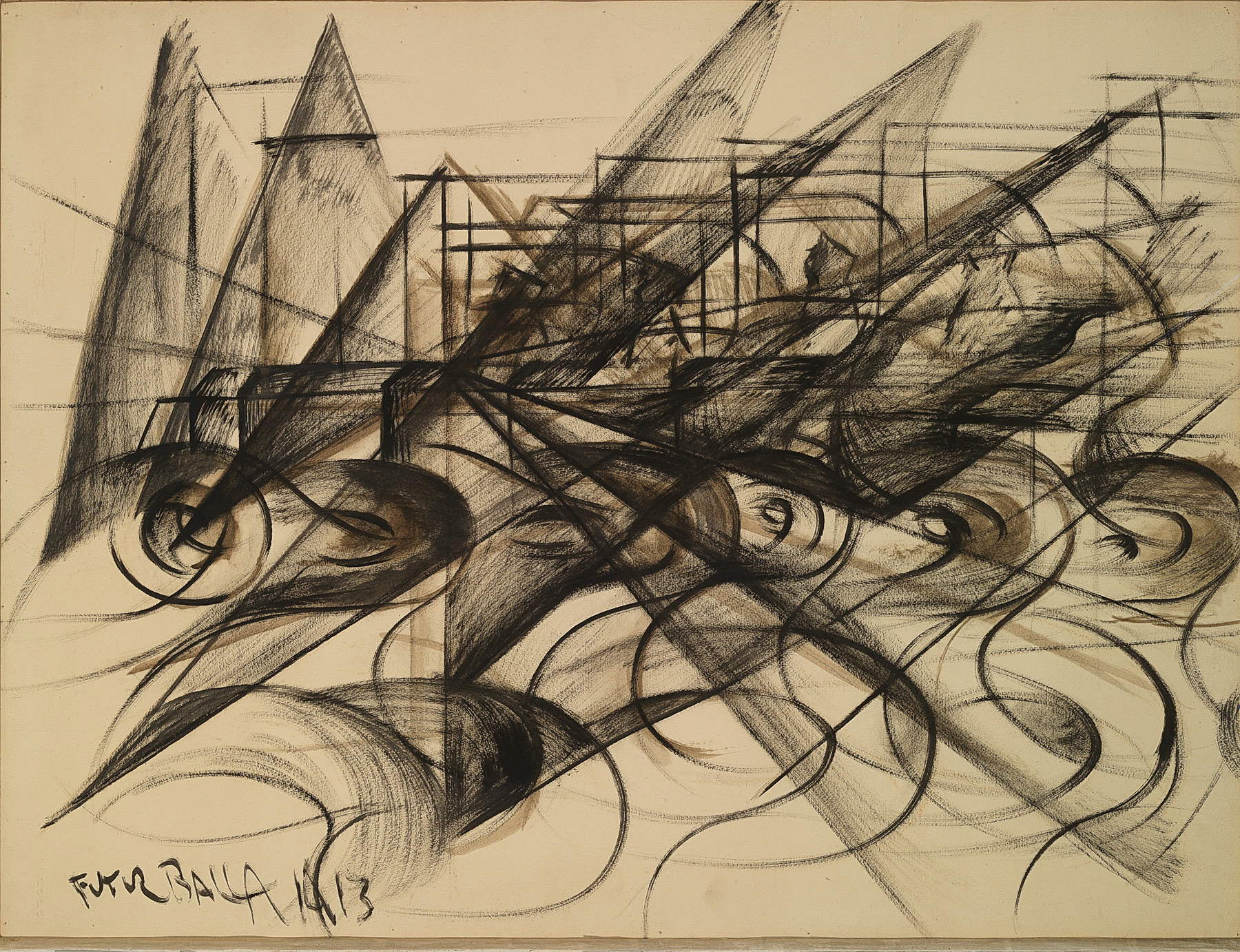

It was Feb. 20, 1909, when Filippo Tommaso Marinetti leapt onto the front page of Le Figaro, after first publishing in a number of Italian newspapers (starting with the Gazzetta dell’Emilia on Feb. 5) a text that still vibrates like a battering ram, the Manifesto of Futurism. “We want to hymn to the man who holds the steering wheel...,” it wrote. A cry, yes, against the past, against all forms of immobility, against that which holds back form, energy, life. Futurism was born as an aesthetic and civil revolution: the running city, the speeding car, bridges raised to the sky. Painters such as Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini joined Marinetti, seeking not to capture static forms, but to return the movement itself: the step, the jump, the traffic, the wind whipping faces. Every brushstroke is an impulse, every line a trajectory, every object an explosion of energy.

Futurism proclaimed the beauty of speed, the power of the machine, the force of progress. Buildings, cars, bicycles, factories, cities-everything became an aesthetic subject, everything screamed dynamism. Painting and sculpture broke down into overlapping planes, broken lines and vibrant colors, not to reproduce reality, but to translate it into visual experience. It was an art that spoke of energy, of intensity, of life in motion, and did not stop to contemplate.

And today? Perhaps that 1909 cry has not entirely died out. There is no need to force parallels; it is enough to observe how the contemporary visual world is shot through withan anxiety of movement. Animations that break up the image, social media feeds that scroll nonstop, slanted logos, industrial designs that seem to move even when stationary. They are not direct “children” of Futurism, but they inhabit the same sensibility: one that sees in speed a form of expression, in dynamism a language. It is a hypothesis, a possibility of reading, a thin thread that connects their search for energy to the visual frenzy of our times. But the narrative of Futurism is not just about momentum and diagonal lines. Inside are searing biographies, radical choices, profound contradictions.

Balla, for example, sold all his pre-Futurist works in 1913 and hung a sign on his studio that read “Balla is dead. Here we sell the works of the late Balla.” A gesture of total break with the past. Boccioni, soon after, mixed painting, sculpture, architecture, wrote manifestos and theoretical texts, seeking a total art that was not limited to the canvas. And then there is the difficult aspect, the less celebrated one: the exaltation of war, the link with nationalism, the phrase “war the only hygiene of the world” that still weighs like a historical responsibility. Understanding Futurism also means accepting its shadows, recognizing that its aesthetics were born within complex political and cultural tensions.

Reflecting on our contemporaneity with Futurism in mind then becomes an exercise in sensibility, not genealogy. A slanted logo, an advertisement that uses the diagonal to suggest speed, an interface that glides with a fluid finger gesture, are all elements that, without being “descendant,” seem to converse with the same urgency as they once did. The Futurists spoke of “simultaneity of perceptions,” and something of that simultaneity survives in the visualoverload of our screens, where everything happens together, everything flows, everything demands attention. Futurism offers us not answers, but a lens: speed as form, energy as language, movement as desire.

This is not to say that social or contemporary graphics “derive” from Futurism: that would be simplistic. Rather, it is a matter of recognizing in today’s imagery a similar tension, a kind of echo. The rejection of immobility, the urge to emerge, the need to transform every image into a dynamic gesture. The flowing feed does not wait, it pushes. Design does not want to stop, it accelerates. Visual communication lives in the rapidity, in the immediate impact, in the rush. And perhaps, even without meaning to, it speaks the same language that the Futurists tried to invent a hundred years ago, that of a world that never stands still.

In reading Futurism within the contemporary it is worth not forgetting that that celebration of speed, that rush toward the new, also had a long shadow. The hero of the machine was also the hero of the war machine, and modernity, for the Futurists, did not advance gradually: it broke through, smashed, erased. Understanding Futurism then means grasping its dual nature: a gesture of extraordinary aesthetic imagination and at the same time a political, radical, even brutal act. And it is perhaps precisely this ambivalence that still makes it a useful tool for reading our present, because it reminds us that every acceleration brings with it a risk, a desire, a wound.

Futurism’s narrative does not remain confined to its time: it tells us about the digital city, the scrolling screen, the visual consumption that does not let you breathe. It is an echo of that desire to “reconstruct the universe” that Marinetti proclaimed, rewritten in today’s forms.

To read Futurism today is not to seek forced kinship, but to recognize that certain insights can resurface in different, unexpected, even unconscious ways. And perhaps, the next time you scroll through a feed or watch an advertisement gives the impression of projecting forward, you will be surprised to sense an underlying similarity: a drive, a vibration, a visual impulse that does not want to stand still. It is not a legacy to pinpoint precisely, but an impression, a reverberation. A way of realizing that some ideas, when born with force, keep moving, even a hundred years later.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.