The exhibition on Futurist aeropainting that is on view until July 3 at the Labirinto della Masone in Fontanellato has explicit and declared aims of completeness: Dall’alto. Aeropittura futurista (From Above. Futurist Aeropainting), the exhibition curated by Massimo Duranti that has gathered together, among paintings and sculptures, a hundred or so fruits of that season, actually stands as a rather exhaustive chapter in the long succession of exhibitions on Futurism, and particularly on aeropainting, that have followed one another in recent years. It could be defined as a recapitulatory exhibition, and at the same time as a photograph against the prejudices that have always accompanied Futurist aeropainting: for example, the idea that we are dealing with a second-rate Futurism, when in fact Enrico Crispolti himself, who coined the definition of “Second Futurism,” specified that it was a different kind of research from that of the early Futurists.

A fruitful time of scholarship on the subject has helped to largely dispel at least the most tenacious preclusions, so that today it is becoming increasingly difficult to come across stubborn refusals. Yet still not so long ago, in 2005, the Guardian’s art critic Jonathan Jones could write that the Futurist aeropainters deserve to be buried and forgotten for all eternity, or at least exhibited for what they are: documents of barbarism (“they deserve to be buried and forgotten for all eternity, or at most exhibited for what they are: documents of barbarism”). An exhibition on Futurist aeropainting had been held that year at the Estorick Collection in London: Jones found the link between those artists and the Fascist regime and their wartime passions unbearable, and evidently the only inference for him was a review trimmed with a pen stroke, resulting in the total dismissal of aeropainting. The reader can rest assured: no one forgives the futurists who survived the so-called heroic phase of the movement their undeniable liaison with the regime. The argument, however, is far more complex: aeropainting was a trend that unfolded throughout twenty years of the history of the Futurist movement, which cannot be made to coincide exclusively with the images of the bombings of World War II (which, on the contrary, constitute the terminal phase, as well as the most stubbornly ideological one, of an experience that by the date of 1940 had already said almost all it had to say), which arose from assumptions alien to the exaltation of Fascism, and which also included artists who were not interested in the regime, if they did not later become openly hostile. It should therefore be recalled, for example, that when Tullio Crali, Tato and Alfredo Ambrosi were getting excited about painting the torpedo bombers in action during the battles of World War II, another aeropainter, Uberto Bonetti, was captured by the fascists because he had collaborated with the partisan groups in action along the Gothic Line (and, moreover, it was precisely a bombing that would destroy his studio). Or that Fedele Azari, the forefather of the aeropainters recognized as such by his colleagues, died by suicide well before part of the movement went into a frenzy over the warlike visions that populated the works of the 1940s. Or again that there were artists who radically changed their ideas. One thinks of Olga Biglieri, the “Barbara aviatrice futurista” who after the war embraced pacifism without hesitation. Or Regina Cassolo, who according to Vanni Scheiwiller refused to participate in the 1942 Venice Biennale in controversy with the regime.

And, speaking of Barbara and Regina (the Futurists often signed themselves either by their first name or by a pseudonym), the neophyte who approaches an exhibition of Futurist aeropainting for the first time might be surprised to note the number of women aeropainters and aviators, especially if one thinks of the distorted readings that have been given of the famous passage in the 1909 Manifesto in which Marinetti proclaimed the “contempt of women.” Now, perhaps anything can be said of Futurism except that it was a misogynist movement: it is well known, meanwhile, that the targets of Marinetti’s polemic were on the one hand the romantic woman à la Fogazzaro, and on the other hand the D’Annunzian femme fatale defined by the futurist poet as “snobbish, vain, empty, superficial, cultural , bored, disillusioned,” and that in his 1917 How to Seduce Women Marinetti aspired to voting rights for women, abolition of marital authorization, easy divorce, devaluation of virginity, and free love. His idea of women may therefore be debated, but it cannot be disputed that he wanted to exclude women from his artistic and political action. It is also well known that women were active elements in the movement, and even one of the most violent manifestos, Futurist Recruitment Project for the Coming War, bears the signature of a woman, Benedetta Cappa, Marinetti’s wife who was also a painter as well as a signer of the 1933 manifesto of aeropainting. But it is also true that many female futurists, perhaps because they were less extreme than their male colleagues, less inclined to assume their heroic poses, and obviously burdened by preconceptions, have been forgotten: the exhibition at the Labirinto della Masone also has the merit of devoting to the experiences of female artists such as Leandra Angelucci Cominazzini and Marisa Mori, in addition to the aforementioned Barbara, Regina and Benedetta, a role no less central than that of the men.

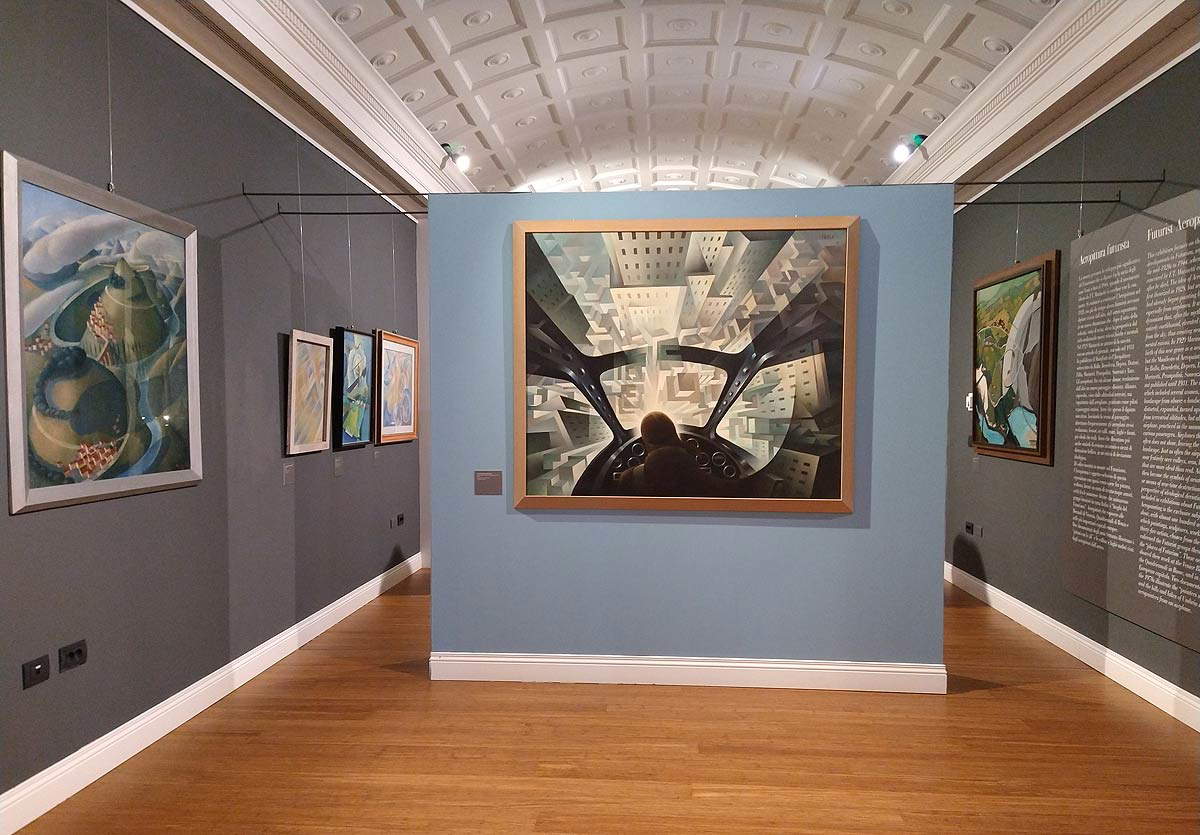

The exhibition welcomes the public with the best-known of the aeropainters’ masterpieces, Incedio città (City Siege ) by Umbrian artist Gerardo Dottori, a work from 1926 that also provides the chronological start of the exhibition: the flames that the fire releases take the form of small pyramids, lit in an intense orange, engulfing the red roofs of a town struck by disaster in the middle of the night, and causing clouds of smoke to rise into the sky in the form of light circles, rendered as if they were dark bubbles. Tradition has it that Dottori had witnessed firsthand a fire that broke out in his native Perugia and that, mindful of that event, he decided to translate it into a powerful image, a view from above of the city with its heart on fire (the arrangement of the flames, moreover, recalls the shape of a heart), where one can perhaps read a reference to the futurist topos of fire that, by destroying old age, purifies and liberates. Dottori can be said to be the first aeropainter, despite the fact that the 1931 and 1933 manifestos had assigned the role of father of the movement to Fedele Azari and his Prospettiva di volo of 1926, absent from the exhibition but recalled by a preparatory drawing, Architettura futurista, of the same year. Before that date, Dottori had already engaged in other views from above, beginning with that Umbrian Spring that he was able to exhibit at the Venice Biennale in 1924. The idea of painting aerial views was already snaking among the artists of the time: as proof, Duranti brought to the Labyrinth a large canvas, titled In volo, by Anselmo Bucci, a painter who had nothing to do with Futurism (indeed: he was among the seven founders of the Novecento group, antithetical to the Futurists), and who found himself to be an “aeropainter by chance,” as the curator writes. The triggers of this fascination with air, however, must be sought even earlier: It is necessary to recall at least the successful novel Forse che sì forse che no by Gabriele d’Annunzio in 1910, and before that the “winged songs” of Paolo Buzzi’s Aeroplani, futurist poems praised by Marinetti himself who, in 1910, flew for the first time with the Peruvian-Croatian pilot Juan Bielovucic, in an experience that inspired him to attack the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature and the 1912 novel Le monoplane du pape.

It can thus be said without fear of contradiction that the Futurists began to fall in love with flight when Mussolini was still a provincial agitator writing in papers of local relevance. Dottori attributed it to the journalist Mino Somenzi, the author, in 1928, of a manifesto of aeropittura and aeroscultura that remained neglected until 2001, when it was rediscovered by Massimo Duranti, according to whom that text represented the “primordial intuition of a futurism that rose from the ground to look from above. It was Somenzi, then, who was the main inspirer, the figure who, Duranti writes in the exhibition catalog, ”intuited to portray the landscape from above, at speed, inventing a world to be seen from the airplane in flight“ and transmitted the idea to Marinetti, who was so enthusiastic about it that he later developed it in the 1931 manifesto. ”The aviation element,“ Somenzi’s manifesto reads, ”bursts with overbearing force into life and materially and spiritually disrupts all the passatist arrangements. It implicitly creates new principles, new conceptions, new sensibilities: it broadens all the horizons of logic and imagination. Art is the first to feel its effect. Aeropainting, aerosculpture, in fact means to feel pictorially and sculpturally from the new point of view: height + space + movement." The latter, in essence, is the triad of aeropainting according to Somenzi’s dictates. The first room orders in very rapid succession the first, and most interesting, products of the artists’ response to Somenzi’s intuitions and to the theoretical formulations of Marinetti and the other signatories of the manifesto, among whom, to account for the complexity of the phenomenon, at least Giacomo Balla should be mentioned, who was never an aeropainter and who would shortly afterwards leave the movement, in controversy with certain of his colleagues, never explicitly named, who according to him were guilty of having joined it out of opportunism and careerism.

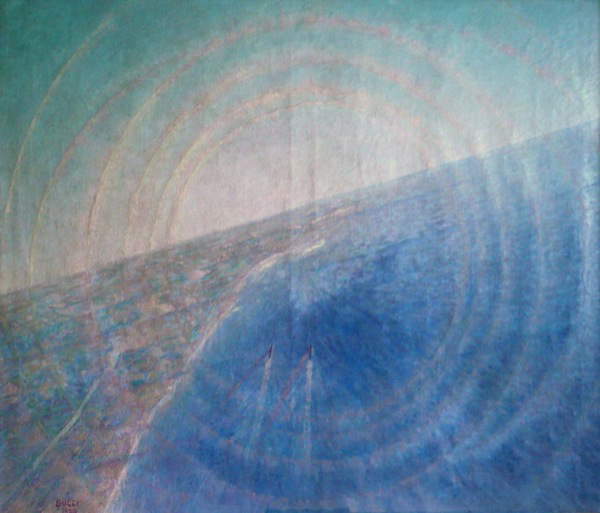

Early aeropainting can be divided into two broad categories, and the purpose of presenting the public with this classification animates the first room of the exhibition: on the one hand, there existed aeropainting driven by a lyrical afflatus, which at times was inflamed with cosmic impulses, and which saw in flight a new perspective, an opportunity for elevation, a further way of overcoming the patterns of the past. On the other, there was aeropainting with a more distinctly documentary character: few tensions toward the infinite, if any, and a desire to show with the brush what reality looked like from up there. Painting in the air is such a new thing that the aeropainting of the first hour almost forgets the medium used to obtain this original view of the world: in the paintings of the early years the airplanes are often not seen, the painters are interested in offering to the eyes of the onlooker unprecedented images of the landscape, distorted, synthetic, inclusive images, images capable of conveying characters of “scattered elegant grandiose density,” as the 1931 manifesto states. Here, then, are the results of the novelties: next to Incendio città by Dottori was arranged a swirling Acrobazia tra le clouds by Alessandro Bruschetti of 1934, which drags the observer into a vortex of clouds conveying all the vertigo of a flight over the Trasimeno countryside, while on the opposite wall the speed of flight allows Benedetta to transfigure a coastal landscape in Rhythms of Rocks and Sea, a work from about 1929 that represents another effective translation through images of that manifesto of aeropittura that set out to impose contempt for detail and the need to synthesize everything.

The vein of poetry that permeates Benedetta’s vision is counterpointed, on the opposite wall, by the infuriated exhilaration of Tullio Crali, who would remain among the most convinced and exalted loyalists until the very end and who can be considered perhaps the most spectacular of the aeropainters: his Incuneandosi nell’abitato is one of the most famous images of aeropittura, a view full of testosterone of a flight from the perspective of the pilot who slips between the buildings of a city, “almost a prelude to 3D,” as Duranti summarizes. In the exact opposite direction, continuing in the room, are the visions of Leandra Angelucci Cominazzini(In volo and Eliche in festa), for whom flight is first and foremost a fact of light and color, a vision that takes on the form of a dream stretching towards infinity. There is a change of register with Giovanni Korompay’sAeropittura (Aeropainting ), which records a piece of sky and mountains seen through a continuous whirling of propellers, and with Tato’s (Guglielmo Sansoni) and Barbara’s views, which offer glimpses of cities from above with descriptive intent.

The second room restores the suggestion of a Futurist picture gallery with paintings and drawings of various formats (the public will find there mostly small works, which, however, do not lose vigor and energy), continuing to investigate the different souls of the Aeropittura movement, with even some juxtapositions between paintings and furniture. Arranged in the corner of the room is the dining room that Gerardo Dottori designed for the Cimino family of Rome, including a work, Flight over the Ocean, which was an integral part of the furniture: it is one of the most dreamlike visions of aeropainting, with the sun lashing the sea and the sky with its rays becoming golden blades, with the rainbow framing the stormy motion of the waves, with the sky described in circles to give the impression of the speed with which the aircraft is plowing through it. Among the paintings that surround Dottori’s masterpiece, Wladimiro Tulli’sAereo sul lago, an extreme synthesis organized with the collage technique, and two 1936 drawings by Fortunato Depero, Aeroplani su Vienna and Scontro aereo: Depero was never an aeropainter, but he nonetheless tried his hand at paintings akin to the genre practiced by his movement colleagues, as these two sheets with their lively narrative taste show.

In the opposite corner of the room, a Spatial Mobile designed by Fillia, aka Luigi Colombo, accompanies three of his works, which give the visitor an account of the more “cosmic” soul of aeropainting with some paintings such as Mistero aereo and Nascita del paesaggio aereo: flight, in his paintings, rises toward mysterious and inscrutable horizons, conquering space, becoming almost abstract painting. Next to Fillia’s works are instead arranged those of the last futurist, Guido Strazza, just 20 years old when he was invited to participate in the 1942 Biennale, still living, and present in the exhibition with some flight drawings from that year. On the central wall, the exhibition unfolds some of the most interesting works of the entire visiting itinerary: it is worth mentioning the abstractions of Osvaldo Peruzzi, perhaps the most geometric of the aeropainters(Verso l’alto is the concise representation of the upward motion of airplanes), and then again the rapid flight of airplanes over Reggio Emilia by the aforementioned Uberto Bonetti, the colorful Aerei by Enzo Benedetto and the irreverent Vomito dall’aereo by Barbara: legend has it that this painting, where all the elements of the landscape mingle to suggest the physical sensations of flight, convinced Marinetti to let the very young Lombard painter, who had yet to be born when the group theorist was flying over Milan with Bielovucic, join the Futurist group.

The visit concludes in the room that explores the ultimate research of aeropainting. There are basically two souls: on the one hand, the painting of those who had begun to paint aerial views with a descriptive slant leads to the depiction of scenes of aerial battles and bombings, while on the other hand, there is a succession of artists who, the panel in the room informs us, “created increasingly abstract forms, alluding to philosophical and spiritual messages,” and nurturing the idea that “flight did not only mean flying over landscapes or exalting the airplane, but also exploring unknown realms of the cosmos.” Belonging to the first case in point are the rhetorical images of an aeropainting that becomes more and more a parody of itself, as Marinetti’s theoretical formulations attest on the one hand (who in 1941 published 56 aeropoetic aeropictorial exaltations of our war, in which he extolled “the bombing that has now entered the lives of peoples,” provided prescriptions for rendering it at its best on canvas, and was self-congratulatory for celebrating the “patriotism of motorized war and no less searing of Italian passion for art”), or some of the works in the exhibition such as Osvaldo Peruzzi’s Aeronaval Battle of 1939, the biplanes that appear in an Untitled by Tato circa 1940, but also Alfredo Ambrosi’s Flight over Vienna from 1933 and Tullio Crali’s Tricolor Propellers, which as early as 1930 hinted at how aeropainting would lend itself to ideology, either through convinced adherence or opportunism. It is true that futurism never officially became art of the regime, but it had tried: and it is true that Somenzi had drawn very distinct boundaries between futurism and fascism, stating with conviction that the former is art and the latter is politics, but this separation did not prevent him from writing in 1933 that the “aereovita” would inspire the artistic and even political activity “of Fascist Italy created by the futurist genius of Benito Mussolini the aviator.”

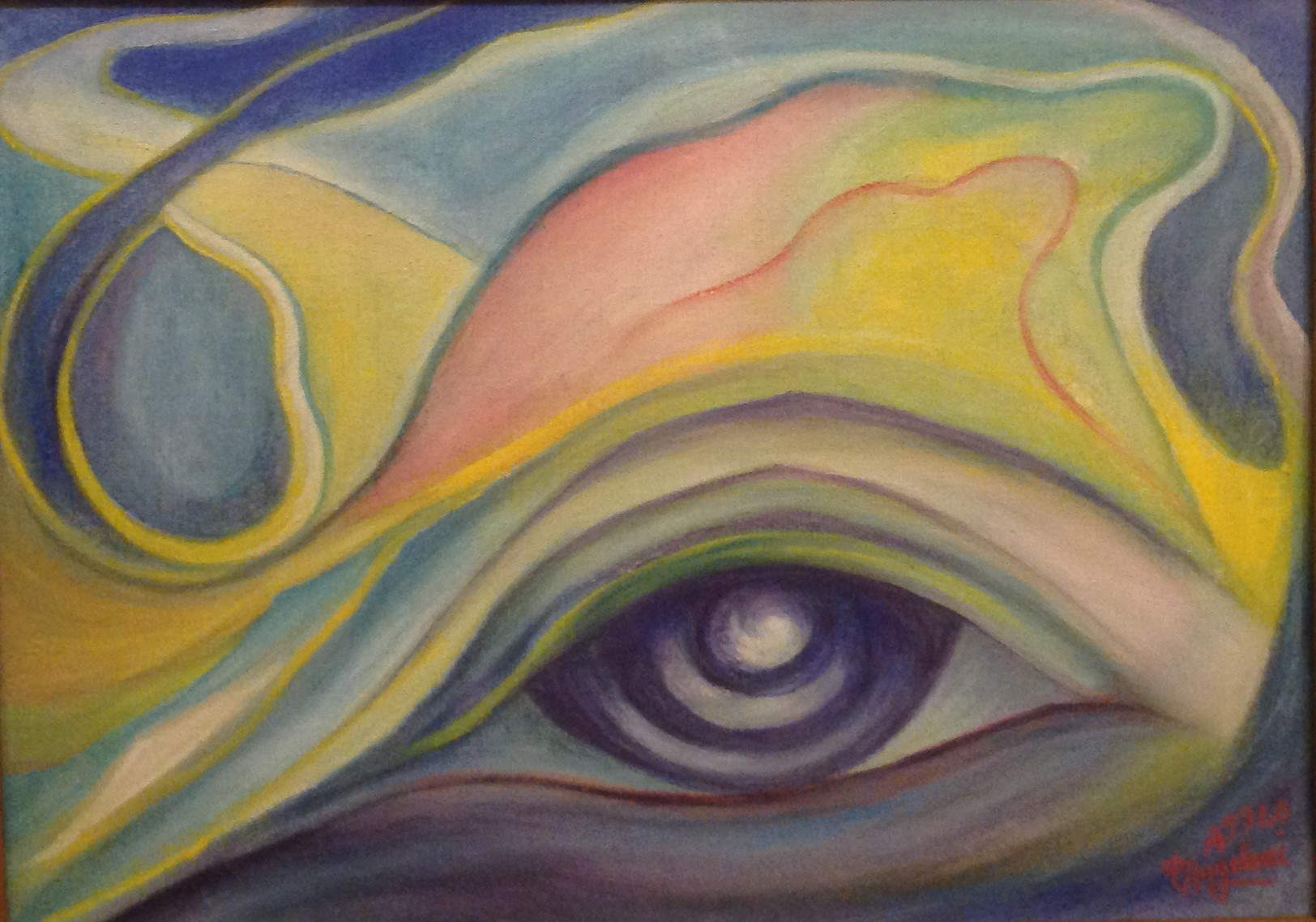

More interesting, then, are the results of cosmic aeropainting, which proceeds with increasingly visionary images to the point of verging on mysticism: tending toward this direction are the paintings of Enrico Prampolini, who as a young man wished for the bombardment of the passatist academies and in his maturity produced visions such as Islands in Space that almost recall the Surrealist avant-garde, or again the abstractions of Nicolaj Diulgheroff (displayed cleverly next to a 1918 Spatial Plasticity by Giacomo Balla, as if to say that it is the Turinese artist who is the father of all Futurist syntheses tending toward abstraction), or Leandra Angelucci Cominazzini’s Awakening, a sky that takes the shape of an eye in an image that brings to mind the works of the Symbolists. The exhibition closes chronologically and ideally with a view by another artist who had nothing to do with the aeropainters, the Cimbrian Rheo Martin Pedrazza, who in 1958 painted a bird’s-eye view of a Dresden disfigured by World War II bombings (these were, one would think, the results of the war decried by the Futurists: the voice of Anton Giulio Bragaglia, the author of Futurist Photodynamism, who as early as 1916 launched his exhortation that “before the victory of arms, the civil guerravittoria of the brain and of works” be engaged), had remained entirely isolated. It is a painting that represents a hapax in the career of an artist who never took an interest in painting from above, but who evidently did not remain immune to the allure of that poetics, even when it had been overwhelmed by history.

There is also no shortage of aerosculpture works in the exhibition, without which a survey of the relationship between Futurism and flight would necessarily have been incomplete: these are sculptures with elongated, vertical forms, such as Umberto Peschi’sOasis of Peace, where serenity for the sculptor is a flight of airplanes, and Renato Di Bosso’s Parachutist in caduta, an artist who “synthesizes action, making it abstract, in the manner of Boccioni” (so Duranti). Thus, from the exhibition at the Labirinto della Masone emerges, in all its substance, a far more composite and much less compact panorama than that which certain hackneyed vulgarizations have propounded to us over the years. To curator Massimo Duranti, then, goes the merit of having ordered an exhaustive exhibition, honest in affirming its shortcomings (venial: these are mostly paintings on which the exhibition could not rely) and in reiterating the ties that aeropittura had with the regime, capable of presenting the public with a meticulous compendium. But the main merit, beyond the valid historical rearrangement (with which it was once again reaffirmed that the paternity of the theoretical conception of the movement belonged to Mino Somenzi, as mentioned above), lies in having ordered a clear and exceedingly accurate exhibition in presenting the various, multiple, multifaceted and sometimes opposing tendencies that gave shape to Futurist aeropainting. From Above is, moreover, a title that could not have been better centered: for, from above, a world that had not yet been explored from the perspective of the sky could be seen in so many ways. With the exaltation of those who glorified the power, even destructive power, of the new mechanical medium. With the poetic sensibility of those who identified in the airplane a way to observe the landscape as no one had ever succeeded before. With the attitude of those who believed that approaching the vastness of the sky nourished the spirit, elevated the soul to the same heights, fostered the union of self with the cosmos. And the exhibition succeeds with great effectiveness in bringing out all these souls.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.