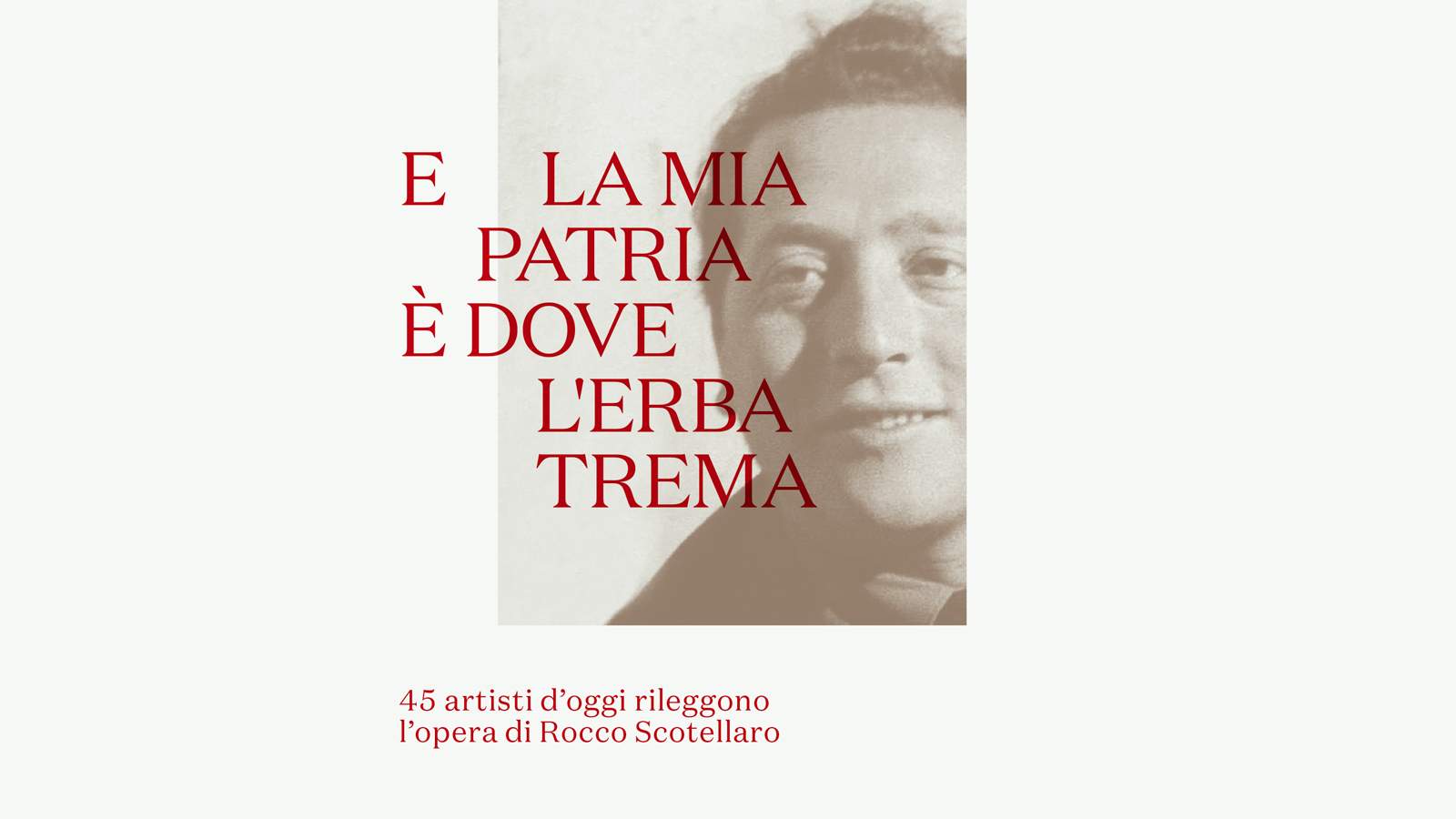

As part of the celebrations for the 100th anniversary of the birth of the Lucanian poet Rocco Scotellaro (Tricarico, 1923 - Portici, 1953), promoted by the Region and APT Basilicata under the patronage of the Municipality of Tricarico and the Matera Basilicata 2019 Foundation, the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art pays tribute to him with the exhibition AND MY COUNTRY IS WHERE THE GRAPE THREATS. 45 artists of today reread the work of Rocco Scotellaro.

The exhibition, curated by Giuseppe Appella, welcomes 45 artists from seven generations: Carlo Lorenzetti, Ruggero Savinio, Mario Raciti, Giuseppe Pirozzi, Paolo Icaro, Giulia Napoleone, Claudio Verna, Emilio Isgrò, Mario Cresci, Assadour, Giancarlo Limoni, Mimmo Paladino, Stefano Di Stasio, Sandro Sanna, Ernesto Porcari, Gregorio Botta, Giuseppe Modica, Giuliano Giuliani, Nunzio, Lucilla Catania, Roberto Almagno, Claudio Palmieri, Giovanna Bolognini, Giuseppe Salvatori, Gianni Dessì, Marco Tirelli, Felice Levini, Enrico Pulsoni, Salvatore Cuschera, Andrea Fogli, Franco Fanelli, Giuseppe Caccavale, Elvio Chiricozzi, Elisabetta Benassi, Giuseppe Capitano, Ciro Vitale, Giuseppe Ciracì, Pierpaolo Lista, Francesco Arena, Alberto Gianfreda, Laura Paoletti, Ilaria Gasparroni, Antonio Della Guardia, Veronica Bisesti, Ado Brandimarte.

These are artists who have had constant relationships with poetry, often from the regions Rocco has frequented. To these, seven months ago, the volume Rocco Scotellaro, Tutte le Opere(Mondadori Editore Milano 2019) was sent, for a reading-comparison that would lead not only to the creation of a work but also to a written page useful for highlighting the word-image relationship and how appropriate it was to talk about Scotellaro, not only from a sociopolitical point of view but also on a more exquisitely literary level. Precisely because, as Emilio Isgrò writes in his page present in the catalog published by Silvana Editoriale, “it is enough to read a few verses to feel that precisely Scotellaro’s music, with all its popular cantabile, is radically different from the hermetic one.” And, moreover, “to signal whether it is not possible to reopen for the South, precisely today, the messianic promise of growth and salvation always affirmed and never fulfilled.” Because “it is of art and literature, that is, of disinterested and strong dreams, that today politics needs to refound itself.”

A way to revive the intense political-cultural debate of the first half of the 1950s, but also to take note of Scotellaro’s wide interests evident in his journalistic prose, film writings and artistic frequentations (through Mauro Masi- Michele Giocoli-Remigio Claps first, Carlo Levi, Ernesto De Martino, Adriano Olivetti, Amelia Rosselli, Giorgio Bassani, Leonardo Sinisgalli later), all of which addressed the instances and needs proper to our time. Which we find in the titles of the works created for the occasion, using all the languages of contemporaneity: I am a blade of grass, Oso, like the tree of the wind, Life huddles within four walls, Pyramids of stars, The face of earth we have, Between you and me I want to plant an orchard, The open-mouthed sky, The earth holds me, Peasants of the South, A breath can transplant my seed far away, It’s daylight, White for Rocco, The peasantry’s turba, Other wings will flee, Tomolo, Distant sea, One is distracted at the crossroads, Where the sky trespasses, I am one of the others, Even a stone, Always new is the dawn.

Rocco Scotellaro was born in Tricarico (MT) on April 19, 1923, to Vincenzo, a shoemaker, and Francesca Armento, a seamstress and town scribe. He attended schools between Tricarico, Sicignano degli Alburni, Cava dei Tirreni, Matera, Potenza and Trento, where he received his classical high school diploma in ’41 and had Giovanni Gozzer as a teacher, from whom he learned the first theoretical rudiments of socialism. Due to the death of his father, he was forced to return in ’42 to Tricarico from Rome, where he had enrolled in the Faculty of Law: he transferred to the universities of Naples and Bari, without ever obtaining a degree.

In ’43 he met the southern epidemiologist Rocco Mazzarone, destined to remain a fixed reference presence; he began an intense activity within the Tricarico Liberation Committee; in December of the same year he joined the Socialist Party. At the age of twenty-three, in ’46, he was elected mayor of Tricarico: his interpersonal skills guaranteed him attention and esteem even from the ecclesiastical hierarchies, which were very important in the life of the town. In May ’46 he met Carlo Levi and Manlio Rossi-Doria, to whom he formed a sincere friendship. As regional inspector for youth labor, Scotellaro works for the protection of laborers, an issue he is simultaneously addressing in verse and prose. He saw the need for greater participation of the population in political and institutional life and realized this goal with “village councils” and the founding of a hospital, inaugurated in Tricarico in ’47, which benefited from the contributions of many, even in small shares. Reelected mayor in ’48, he stands in solidarity with peasants in the occupation of land. He participated in the Assize for the Land, held in Matera on December 3 and 4, 1949, and was elected a member of the regional committee of the Assize for the Rebirth of Southern Italy.

During these years Scotellaro made friendships that were decisive in the completion of his intellectual profile: with George Peck, the American historian-anthropologist who studied the Tricarico community; with Friedrich G. Friedmann, the German-American philosopher who had come to the Mezzogiorno to learn about the Weltanschauung of the peasant; with Ernesto De Martino; and with Adriano Olivetti.

His arrest, on Feb. 8, 1950, for an alleged crime of extortion with reference to episodes dating back to a few years earlier, kept Scotellaro in Matera prison between February and March: here he jotted down his first ideas for L’uva puttanella. The affair, very corrosive on the human level, has a happy outcome from the judicial point of view: on March 24, 1950, the Investigation Section of the Potenza Court of Appeals acquits him “for not having committed the fact” or “because the fact does not constitute a crime,” and, ordering his release, expressly alludes in the sentence to a concerted “political revenge.” Embittered, he resigned as mayor in May 1950 and left Tricarico for Rome and then for Portici (NA), called by Rossi-Doria to theAgricultural Economics Observatory, where he participated in the drafting of the preliminaries for the Basilicata Regional Development Plan commissioned by SVIMEZ. Under Mazzarone’s guidance, he worked on sanitation problems; he also wrote detailed reports on illiteracy and schooling, channeling a sociological interest that, in May 1953, led him to agree with Vito Laterza, through Vittore Fiore, on the book Contadini del Sud. Urged on by his peasant friends, with whom he did not break the continuity of the deep relationship of trust, he ran in the provincial elections of May 1952, despite some friction with the materano PSI; this time, however, he did not emerge victorious.

On December 15, 1953 Scotellaro died suddenly of a heart attack in Portici, to the heartbroken disbelief of his many friends and with many projects under way. Contadini del Sud is awarded posthumously for the investigation in ’54(San Pellegrino Prize); post mortem also comes the Premio Viareggio ’54 for the poems of È fatto giorno.

We manufacture memories. The poet, on the other hand, creates them. Rocco Scotellaro had a short but intense life, perhaps because, as he himself wrote, he understood “all too well the years and the days and the hours,” and he chiseled many of them. In his political, sentimental, synaesthetic words he embedded thoughts that smelled of rosemary. Going through the parts of the heart, the one on which he held his hand as he walked (“by force they might steal it,” he said), he restored his integrity as a man who loved much and understood too much. His was a fatherly, patient, welcoming lucidity.

A strong, steadfast man who contemplated the night and its constellations of almond blossoms. Nights full of hope and certainty about the fragile but absolute beauty of the world and of a land from which to learn everything, while the roots cling and the fronds are moved by the wind.

The memory of Rocco Scotellaro at the National Gallery, is multiplied by 45, so many are the artists called to return a work suggested by the experience of reading his poetic word, a renewed witness to be entrusted to the generations to come.

For all information, you can visit the official website of the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art.

|

| In Rome, 45 contemporary artists reread the poems of Rocco Scotellaro |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.