If one were to take a few minutes in a museum or church to observe the typical behavior of the public in front of a polyptych, one would find that there is a large number of visitors who pay little attention to the predella, observe it with a little complacency, sometimes not even linger on it: it is usually the most neglected part of a polyptych. In spite of the fact that, paradoxically, most of the time it is also the easiest to observe, since it is often at the eye level of the viewer. This is a mistake, for there are often predella that are more interesting than the panels that surmount them. Vasari was convinced that the case was also made for the predella of the Griffoni Polyptych: speaking in the Lives of its unparalleled author, Ercole de’ Roberti, the Aretine wrote that “he painted [...] in San Petronio, in the chapel of San Vincenzio, some stories of small figures in tempera, so well and with such beautiful and good manner that it is hardly possible to see better nor to imagine the toil and diligence that Hercules put into it, there where the predella is much better work than the panel.”

The predella of the Griffoni Polyptych today lives on by itself: the historical vicissitudes that the complex altar machine painted by him and Francesco del Cossa had to face over the years caused the predella to be detached from the rest of the work, and today it is preserved and exhibited in the rooms of the Vatican Pinacoteca, far from the other compartments, which are scattered among Milan, Paris, London, Washington, Ferrara, Venice, Gazzada, and Rotterdam. The polyptych had been dismembered around 1725, when Monsignor Pompeo Aldrovandi, the new owner of the chapel where the work was kept, had the painting removed and dismantled in order to obtain room paintings to be placed in the family residence in Mirabello. An ill-advised choice, not only because the unity of the whole was being irreparably destroyed, but also because the operation was a prelude to what was to come later: the individual portions were placed on the market and took the most varied destinations, never to meet again, until the exhibition organized in Bologna between 2019 and 2020 at Palazzo Fava, which reunited the polyptych after almost three hundred years.

However, even at the exhibition the various portions were displayed separately: it was the facsimiles that were responsible for the reconstruction of a hypothetical arrangement that the various panels might have had originally. The advantage lay in the fact that each individual element of the polyptych could be admired with due care and precision. Including the predella by Ercole de’ Roberti.

|

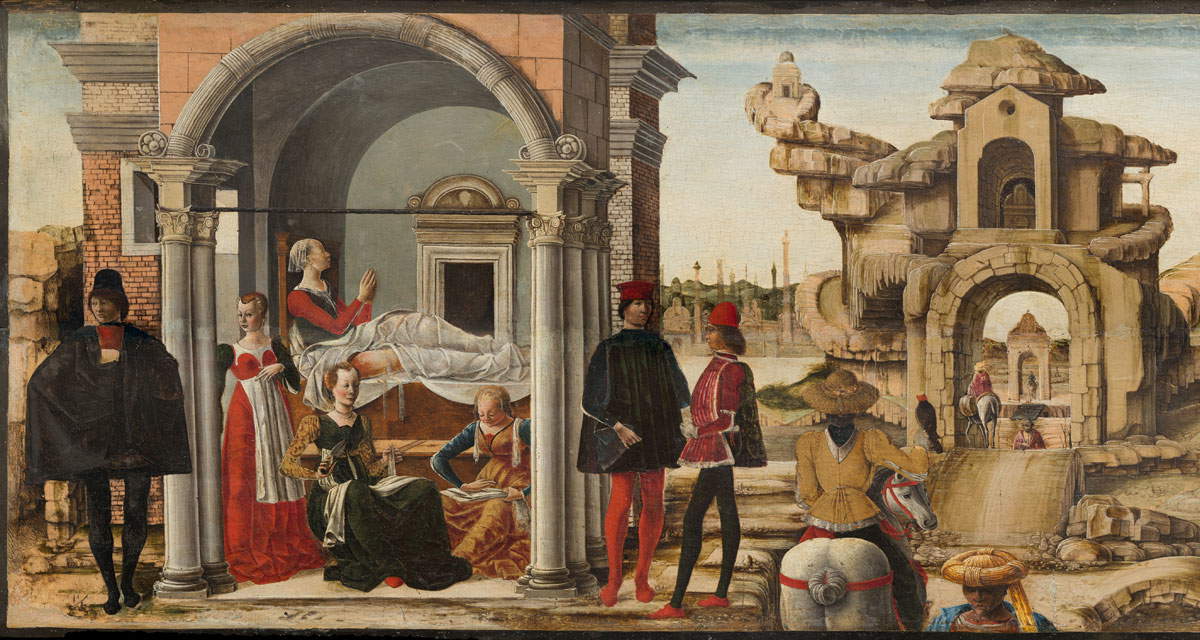

| Ercole de Roberti, Stories of Saint Vincent Ferrer, from the Griffoni Polyptych (1470-1472; tempera on panel, 27.5 x 214 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Vatican Picture Gallery, inv. 286) |

|

| Ercole de Roberti, Stories of Saint Vincent Ferrer, detail |

|

| Ercole de Roberti, Stories of Saint Vincent Ferrer, detail |

|

| Ercole de Roberti, Stories of Saint Vincent Ferrer, detail |

|

| Ercole de Roberti, Stories of Saint Vincent Ferrer, detail |

The great Ferrara painter had here painted the miracles of Saint Vincent Ferrer, that is, the saint whose figure stands out in the central compartment, painted by Francesco del Cossa: the Spanish preacher had been canonized in 1455, the commission for the work had matured in Dominican circles, and the Order was at the time engaged in a complex operation to spread the cult of the new saint. In the predella, the saint appears twice: in the center, as he performs one of the five miracles described by Ercole de’ Roberti in a single, seamless scene, and at the top, as he pops out of a kind of interspatial gap opened in the sky to perform another. Hercules is a formidable director, one of the best in the fifteenth century, perhaps in the entire history of ancient art: the sequence he places before our eyes has strong cinematic accents, it is a film ahead of the letter, it is a fascinating story told with supreme narrative wisdom, it is an open window on a colorful, frenetic, bizarre world, it is the birth of a mind that knows how to organize with the flair of the engineer but also knows how to escape with a visionary imaginative flair. Because those that Ercole de’ Roberti fixes on the predella are not facts seen and recorded, they are not punctual accounts: it is, if anything, “the image that lightning flashes to the mind and is immediately overwhelmed by another that succeeds it and almost overlaps it,” Giulio Carlo Argan would have said.

The five miracles of St. Vincent Ferrer, namely the healing of the paralytic woman, the resurrection of the Jewish woman, the rescue of the child from the burning house, the healing of the wounded man, and the resurrection of the child killed by the maddened mother, flow through a landscape somewhere between the real and the fantastic, appearing to us to be alive, but almost with the same consistency that dreams have: we seem to be living it, but we also see grotesque deformations, surreal situations, and unexplainable appearances.

Ercole de’ Roberti’s imaginative frenzy is substantiated, first and foremost, in architecture. Longhi, in his Officina ferrarese, spoke of “capricci d’inventore di giunti architettonici,” seeing in these gimmicks an echo of what Ercole had already proposed at Palazzo Schifanoia: “crammed and tied wicker bundle arches; cartouche modillions with deep double volutes, as he had used for the chariot of Lust at Schifanoia and at the top of the arches within the San Lazzaro altarpiece; and, in views of distant cities, just as in the imaginary Rome within the coat of arms of the Schifanoia fresco, box-shaped edicolets surmounted by half-buried arches, and columbaria and trulli, and Assyrian domes, and spools and bobbins.” And then, in the poses and attitudes: “a repertoire so rich in motions of stops, pauses, and breaks,” Longhi wrote again, “so flamboyant and cruel, as to overflow genius for every verse.” In the more than two meters along which the predella unfolds, Ercole de’ Roberti has poured a multifaceted and nuanced sampler of all human emotions: the heartfelt devotion of the healed paralytic, the concentration of the two women in front of her attending to household chores, the relaxed tranquility of the two men in Renaissance garb conversing with each other, the agitated amazement of those witnessing the resurrection of the woman in the red robes, the despair of the mother who sees the child on the roof of the house threatened by thefire, the toil of the men at work to put it out, the seraphic confidence of the little one who sees the saint appear and understands that perhaps things will turn out for the best Look then at the extraordinary variety of poses in the colorful world of Hercules: the man collecting water from the well, the one who, with quotation from the Capitoline Spinarius, looks at his wound, the sleeping woman, the child putting his hands in his mouth. There is all humanity, in his predella: men and women of all colors whom the Dominican saint protects by peeking out of the sky and extending his saving gesture over that forest of open architecture, ruined houses and magnificent temples, in which the artist pours all his antiquarian culture.

It almost seems to us that the miracles become a pretext for giving free rein to the imagination: Hercules may not be a heretical artist, but he is certainly a totally unconventional painter. For Argan, his predella is a pure mechanism of imagination, which, while not renouncing the linear dynamism that was typical of Cosmè Tura and the entire Ferrarese school, skips the religious motivations that animated Tura’s works. “Poetics of excitement,” said Argan. Hard not to agree with him.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.