All of Correggio’s frescoes and almost all of his mobile paintings are bearers of particular meanings, not often easy to decipher, that explicate values of a Christian scope and that flow from deep meditations which lead to his well-known compositions, rich in spiritual or anagogic density, but always “happy” in the highest sense of the term. We must thus investigate from the inside the personality of the painter, of whom, moreover, no written expressions or revealing conversations are known except Vasari’s hints of his simple life and evident faith. From his works, however, we can say that he was soon an immediate master of the brilliantly artistic translation that is that of genius: from intimate cultural elaboration to figurative creation, that is, the metamorphoses from the unspeakable to the visible. On Correggio one is called to always consider the full use of iconology.

The theological axis that accompanied it was that of biblically seeing eternity not as an infinite passing of days, but as - in reality - an absolute present. This truth enabled him to speak pictorially above time, and we can understand this in various subjects.

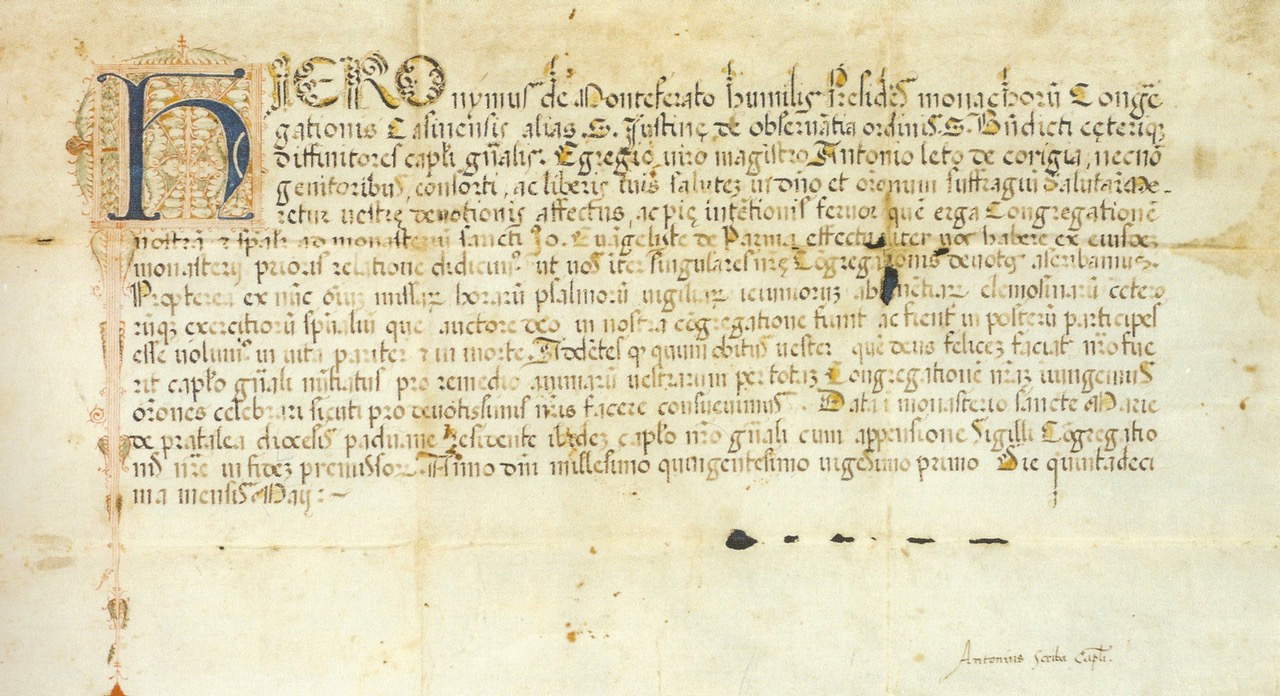

The evidence is all in Correggio’s paintings: from them we can draw his studies, both physical and philosophical, his vivid naturalistic predilections, the limpid architectural wisdom and power, the influences that his great masters such as Mantegna and Leonardo had on him. Above all, we can take in that total Benedictine imbrication that always accompanied him in life and included knowledge “ab imis” of the Holy Scriptures, the Gospels, and the fruits of contemplation(cum - templum - et actio). Here it would be nice to elaborate further, but we will limit ourselves to mentioning that Antonio Allegri elaborated each of his compositions either supported by a firm theological structure or by a smooth and strong moral induction. It will not be useless to point out that he, in his early thirties, was welcomed and immersed within the Benedictine Order with full participation in the spiritual benefits of the monks themselves. Which confirms his intense presence at San Benedetto Po from his early youth and his spiritual formation under the guidance of Gregory Cortese.

Now, to enter into the title of our considerations, the reference goes to a pictorial creation by Correggio on a subject barely hinted at in the Gospel of Mark, where in the Garden of Olives takes place the capture of Jesus, who after Judas’ kiss voluntarily allows himself to be taken. Here begins the event of the “Passion and Death of Christ,” which, for humankind, stands at the center of the great divine plan between the Fiat Lux (the Creation) and the Parousia (the new appearance of Jesus on the Last Day). We must strongly emphasize this centrality!

Correggio captures with extreme emotion what happened on that Thursday evening in the Garden, and of the whole episode he pins on Mark’s account, when Jesus, already surrounded by the manutainers dragging him toward the high priest’s house, instantly healed the ear that Peter had cut off a servant. As they led him away the evangelist notes “a young man, however, followed him, clothed only with a sheet, and they stopped him. But he, having left the sheet, fled away naked” (Mk. 14:51-52). Antonio Allegri drew from it a composition whose singularity has drawn the questioning attention of at least two great scholars, since unlike the few other artists whose paintings or drawings recall that particular jostled detail, Correggio makes the young man the imminent protagonist, the major figure of the whole vision, and makes him run - free, naked and luminous - toward our space, toward us. In the critical vision the question remained, and it is the one we would now like to unravel.

Among the many replicas known today, two specimens that derive from the lost Correggesque original, and which we might therefore call distinctly “Roman” and “Venetian,” are especially in the spotlight. The former is carefully critiqued by the catalog of the Correggio and Parmigianino exhibition at the Scuderie del Quirinale (2016), while for the latter a curious Italian itinerary is underway, accompanied by a willingly printed edition(Correggio, the young ignudo from the Este, Sforza and Barberini collections, Scripta 2025). An itinerary that does not carry the painting and where the book, including the uncertain greetings, fails to grasp the truth of the subject explicated; it also does not dare to declare the possible authenticity of Correggio’s hand. Instead, much of the data derived from the research is respectable.

--

We must then grasp the real protagonism of the running young man who has abandoned his cloth. For this quest it is essential for us to understand well that Jesus’ capture is the end of his preaching (!) for which he became flesh and after which he offered his own life as a sacrifice. And it is Correggio who in deep meditation follows theitinerarium Christi ad lignum Crucis.

Let us therefore read the Gospels. At the moment when he is taken prisoner, on the night of Gethsemane, the reactions of his disciples differ in three ways. The first is that of Peter, who fiercely rebels, draws his sword and begins to use it, striking bloodily, but Christ undoes with his hands the wound to the stricken man and severely restrains his followers who would have wanted to fight. The second is that of John, who was the disciple-John in the ancient usage and who as such is always left beside Jesus; he records the passage his Master has in the house of Annas, and then - bound - the tremendous conversation in that of Caiaphas; the significant silence with Herod; then the supreme conversation with Pilate; and then the last words on the Cross, beside which he had been able to remain. John embodies closeness and faithfulness to the Lord even in the crucial event. The Passion of Jesus Nazzareno thus remains the real episode, firm in history, and Correggio places its beginning at the bottom of the painting, including the kissing of Judas.

The young man fleeing and coming toward us represents the third mode, arranged certainly directly by divine will, and is the mission of continuity of Christ’s own preaching that He wants spread over the whole earth for the coming times. Confirming this role is the adolescent Mark himself, later an evangelist, who thus recalls the emblematic episode by pointing out that after the Resurrection, Jesus told the apostles, “now go into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature” (Mk. 16:14). The cloth left behind and its nakedness rise to the significance that all the apostles’ catechesis is to be whole and total, as Christ delivered it. Correggio’s painting, with extreme awareness on the part of the painter, is thus in truth not a “young man running away,” but it is an Evangelist running toward us. And it is a painter of stupendous depth who declares this through a true imago mentis. An ecumenical event that covers time and peoples.

And the man chasing the young man cannot be a Roman gunman, for beyond the Cedron, in the band sent by the Pharisees that Thursday night, there were certainly no Pilate’s guards. We must therefore assume that Correggio, with much signifying care, wished to represent in it the whole of paganity, to which the Gospel is addressed. For this reason the pursuer appears as pervaded by a kind of restless questioning, between suspicion and desire.

The spread of the Gospel will thus come to intricate all that redemptive part of the time of salvation that God has inserted into eternity, and in this sense we return to the scriptural contemplations that Correggio investigated deeply and poured here into an extraordinary masterpiece of pictorial anagogy.

The author of this article: Giuseppe Adani

Membro dell’Accademia Clementina, monografista del Correggio.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.