Sometimes the past resurfaces with full force in unexpected ways. It is 1711 and the Austrian prince Emanuel dElbeuf has a hole cut in his Portici residence purchased for his wedding to the Neapolitan princess Salsa. There, quite fortuitously, he makes a sensational and unforeseen discovery: he recovers three statues of Vestal Virgins and identifies to his amazement a whole city to be excavated and unearthed, a Roman villa of which all trace and memory had been lost: Herculaneum. Having disappeared from the face of history because of the eruption of Vesuvius (not like Pompeii, which ends up under two meters of lapilli and ash), Herculaneum, after more than one thousand six hundred years, before the Bourbons and the systematic excavations of 1738, was waiting under a petrified slime to return to the light. And it was waiting for him, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who, immediately after seeing those three statues exhibited in Dresden (“the first great discoveries of Herculaneum, masterpieces of Greek art, transported to Germany and venerated there”), left for Italy, or rather: finally for Naples and the southern lands.

At the beginning of the century, as a result of a new worldview, largely, but not only, triggered by the rediscovery of Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748), a fever for the Ancient broke out, a feverish excitement that runs through the entire arc of the artistic parabola of the late eighteenth century, touching every stage of the changes in taste. Indeed, one goes in a short time from considering antiquity a still naïve and amateurish passion to taking care of it with methodological attention: from generic antiquarian interest one passes the baton to a firm desire for excavation documentation, until it becomes a true science. But before, long before artistic practice is transformed and even organized as copy for paper museums, and declined as the creation of a new method of study on the ancient, first of all, there is the longing to know and see, or at least that of copying and imitating the style of frescoes, decorations and furnishings that have re-emerged from excavations, there is the desire to leave and come to Italy and especially to the south. In addition to the iconographic fortune of the ruins, which coincided with the discovery of the south by artists and travelers, the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum opened up new horizons for archaeological research and finally determined a shift in the axis of interest toward Naples and the south of Italy. The city of Naples, the last stop on the Grand Tour, was popular for the beauty of nature, the climate, the eruptions of Vesuvius, and was also considered an outpost for other excursions to rediscover the ancient cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily.

The historical turning point following the rediscoveries of Herculaneum and Pompeii has two implications: first, to resurface what time had buried, and second, to pour it back into the present epoch. For while it is true that with the reappearance of the two cities in Campania, which take on a symbolic value of European resonance, we are witnessing the intensification of a phenomenon that is beginning to lead archaeological expeditions outside Italy as well (“it is no longer the place that is important,” Rosario Assunto argued, “but the absolute ideal of an antiquity, rediscovered and understood, has acquired a new, decisive value: lantichità come futuro”), it is also true that this episode becomes “a discriminating element for a modern indication of taste” (so Anna Ottani Cavina), which transforms the place into the dream of a perfect civilization. It is no accident that the rediscovery of one place undermines the other (Herculaneum, Pompeii, Paestum, Greece, Palmyra... ).

There were, yes, the great excavation campaigns in the south and the devouring fever of archaeological exploration (exceptional is the case of Piranesi), but this cannot have been the only channel for the antiquity’s exemplarity to be imposed: “the cult of antiquity was a catalyst and not a driving force” (Hugh Honour). Archaeological discoveries therefore happen as a result of a new tension that has in fact changed the ideology of the ancient. But how do those who arrive here, in the rediscovered places, transpose the ancient? What ruins and artifacts does he see directly in the archaeological sites? Does he or she not rather simply see and remake the ancient from afar? Through the filter of engravings and prints, and the drawings in the notebooks of those foreign grand tourists who really set foot here, even with effort? After all, the antiquity that interested Italy acted above all “on artists who came from countries where the physical presence of antiquity was almost nonexistent” (Giuliano Briganti): what force do those ruins emanate? What feelings do they arouse? Surprise or dismay, sense of grandeur or rather deep bewilderment? Will they be, and in what terms, a source of inspiration for artists to come? It is true: Herculaneum and Pompeii, swallowed and forgotten cities, sortant du tombeau, represent an unusual and surprising case of archaeological resurrection: it will therefore be legitimate to question and interrogate the sources, documents and especially some representative works of the artists of the time to understand what impact this re-emergence of a hitherto unknown past might have had. Very little was known about Roman painting in those years, except for rare exemplary pieces: “before the findings of Herculaneum and Pompeii,” Egon Corti argues, "the myth of ancient painting could count on very rare confirmations almost only on the Aldobrandini Marriage, in addition to the frescoes of the Domus Aurea.“ So, once resurfaced from beneath the earth, what language did Antiquity speak? What did the ruins communicate through the sculptures, works and frescoes that gradually re-emerged from those places as imposing and majestic or as shadows, painted as barely hinted at? In painting, ”those shadows (especially the figures of the Dancers and the Bacchae) took shape and became so present as to upset, in the late eighteenth century, the terms of the relationship with the ancient world" (Anna Ottani Cavina).

Many have been the meanings with which the ancient has been received. But to what extent is it manipulated, betrayed, reshuffled in the 18th century? Canova, according to Ottani Cavina, excerpts extensively from the excavated repertoire. He does so, for example, starting with the Players of Astragali, an iconographic subject that had been illustrated in the so-called Herculaneum Antiquities. Stylizing with drawing a now radically changed prototype, Canova realizes, Ottani Cavina writes again, “in the happy coincidence of grace and the sublime, the aesthetic ideal prefigured by Winckelmann, that of a grace filtered through the intellect.”

In the works Young Woman Reclining in a Chair (Cambridge) and Dancers (Possagno and Correr), the extreme reduction of Canova’s means of expression, in both tempera and drawing, emphasizes an intellectual and modern beauty, determined by a functional and taut line. Springing from an ancient stylistic figure, Canova’s series, inspired by Herculaneum themes, moreover finds in Foscolo’s poetry the most appropriate and seductive literary reference. Again Canova, in the composition of Love and Psyche lying in the Louvre, was instead inspired, as is well known, by Table 15 of Volume I of the Antiquities of Herculaneum where a faun is portrayed with a bacchante. The group is presented as a perfect plastic organism whose compositional directrices form a large X, the meandering or grace lines and the undulating or beauty lines theorized by Hogarth are taken up and enhanced by the elliptical lines favored by Winckelmann of the arms of the figures. Argan called this the metric movement of sublimation.

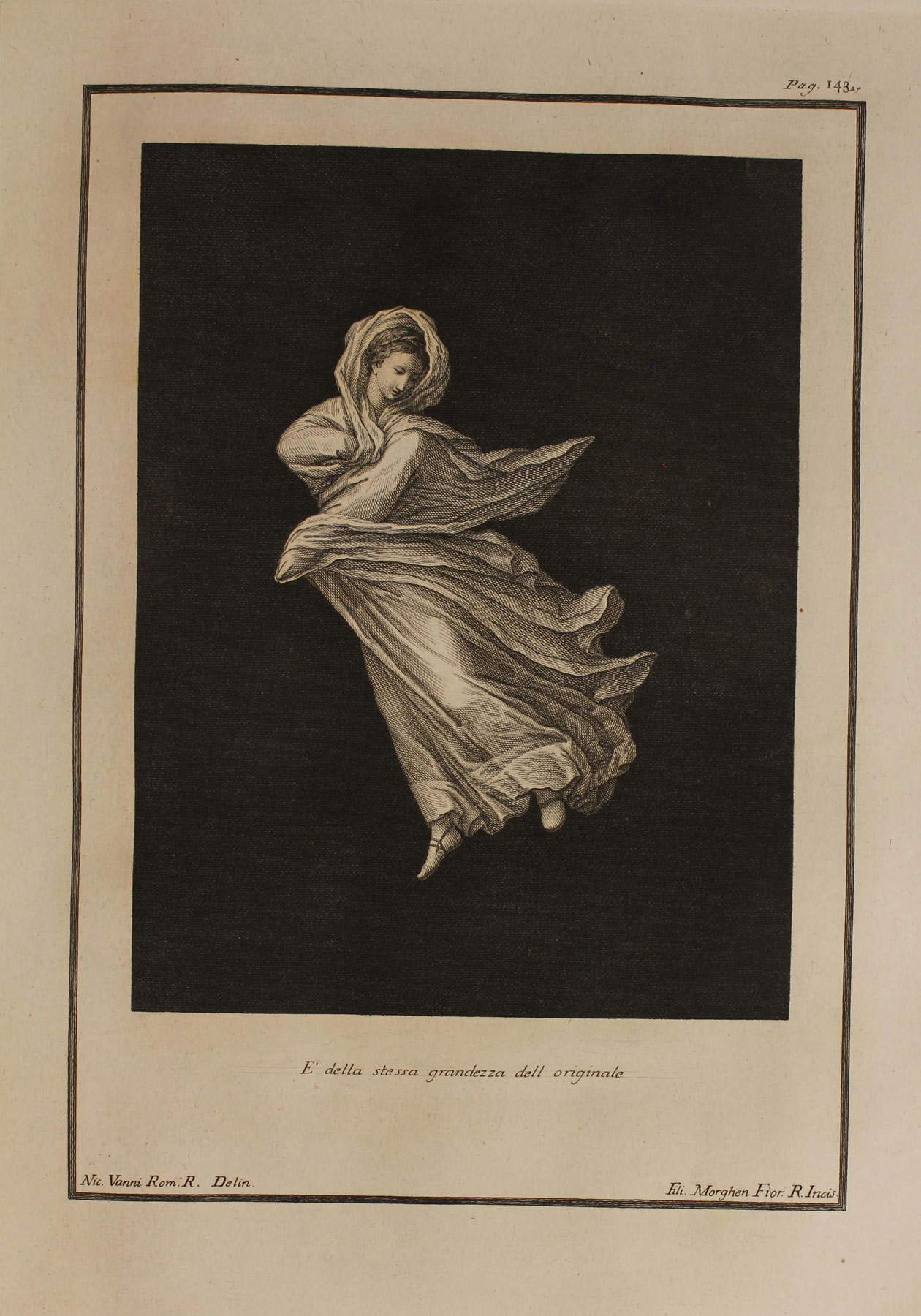

The figurative theme of Dancers is also widely exploited in the 18th century, from Canova himself to Flaxman. Winckelmann, the theorist of neoclassicism, pointed to the Maenads or Dancers of Cicero’s villa as truly exemplary among all the encaustic paintings torn from the walls of Pompeii because “they are as fluid as thought and as beautiful as if made by the hand of the Graces.” In the wake of the enthusiasm for the past that had swept the eighteenth-century generations, the image of the Dancers is reshaped in different declinations. Even in a more stylized form rejected into the flow of the everyday as does John Flaxman, “who drew the games of two maidens in the sunshine of the Italian spring” (Ottani Cavina). The original frieze with maenads, dancers and centaurs, found on Jan. 18, 1749 in excavations conducted by Alcubierre at Civita (now Pompeii), an ancient prototype and a source of inspiration for 18th-century artists, is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples. The relief was arbitrarily composed after detachment, and the figures were originally isolated in the center of the wall, on a black background, and had ornamentation around them with satyrs balancing above the rope and slender candelabra. Would this transliteration perhaps explain Flaxman’s use of contour, bringing the thickness of a relief to the two-dimensional flatness of a drawing? In a direct comparison between the Pompeian fresco and the translation on the engraving of the Antiquities of Herculaneum exhibited, it is noticeable how in the transcription on copper (intaglio) the only one then accessible, takes place, Ottani Cavina reiterates, “a reductive process that tends to privilege lexicality of outline and the abstracting force of a functional and very pure line.” Thus compendiary expressionism and stain, which in the Roman frescoes had brought limmagine to the last stage of formal disintegration, are in the Engraving entirely removed, thus providing another vision of the Ancient. Another theme that constitutes in these years almost an iconographic thread is that of the Seller of Cupids, which refers to the erotic painting of Pompeii, to the so-called fascina. The saleswoman during the 18th century experiences an adventurous history as her iconographic and symbolic apparatus is transliterated from the splendors of daring manipulations by Vien (1763), Füssli (1775), and even later with Thorvaldsen (1832). Robert Rosenblum, one of the foremost experts on neoclassicism, draws a kind of first conclusion and emphasizes how persistent was lambiguity of the antique, “the wide range of stylistic and expressive results” that could be drawn from the prototype.

The key work, the Marchande à la toilette, with which, moreover, Vien participated in the 1763 Salon, juxtaposed with an engraving of a recently unearthed Roman painting, may suggest and confirm once again this multiplicity and flexibility of gazes that takes its cue from the Roman painting. Discovered on June 13, 1759, in Gragnano, on the outskirts of Naples, the painting must have “excited its new public not only by virtue of the dramatic circumstances of its burial in the shadow of Vesuvius, but also because of the primitive austerity of its style as opposed to allimperating [and sensuous] Rococo fashion” (so Rosenblum).

According to Charles-Nicholas Cochin, the paintings found at Herculaneum “do not present at all the art of composing the lights and shadows”; not only that, “the composition of the figures is cold and seems rather treated in the taste of sculpture, without what warmth that painting possesses.” So much so that another anonymous critic, when speaking of Vien’s work, summed up its qualities of strict imitation of the Ancient in this way: “simplicity in the positions of the figures almost straight and motionless, very little drapery, a severe sobriety in the accessory ornaments.”

By comparing Vien’s painting to its Roman source of exhalation (as Vien himself invited the Salon viewer to do) the points of divergence become more conspicuous than those in which limitation is found. This is because the eighteenth-century painting, despite the learned fashionable reference to a recently discovered ancient painting, still sinserted itself in the Rococo sphere and thus presented in an erotic unaccezione.

By comparison, the biscuit group (1785) Wer kauft Liebesgötter?, by Christian Gottfried Jüchtzer, an eighteenth-century master of Meissen ceramics, traces, according to Rosenblum, The excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum open new horizons for archaeological research and finally bring about a shift in the axis of interest toward Naples and southern Italy. lincision of the ancient painting much more than Vien’s painting, retaining more of the geometric severity and therefore a greater archaeological adherence. Even more simplified, more spare than his master Vien, is Jacques-Louis David’s drawing, in that, Rosenblum writes, he “transcribes these forms through the instrument of line alone.” The rendering of the interior and the description of the pictorial mordant are downplayed in favor of a uniform, spartan linear style that reduces the erotic potential of the classical source and brings out the heroic, invigorating simplicity that a revolutionary French generation would have sought in Greco-Roman art. In the light of this small number of examples, one can consider how dissimilarities between interpretations of a single source could suggest, that in the late eighteenth century the same suggestions from the ancient, could produce a wide range of results both stylistic and expressive. And to draw the conclusion that after all “the romantic Winckelmannian image of a remote Greek art, permeated with Mediterranean serenity and harmony” (so Rosenblum) was only one of many possible visions of antiquity.

Around 1800, in fact, the classical world could be reshaped to meet the most disparate demands, of French revolutionary propaganda, romantic melancholy, and archaeological erudition, and thus be, to quote Rosenblum again, “incorporated into visual lexicons as dissimilar to each other as the chastened contours of Flaxman’s classical illustrations, the frigidly voluptuous surfaces of Canova’s marble nudes, or, later, the dense sculptural encrustations of Napoleon’s imperial architecture.”

Enthusiasm for the ancient during the 18th century thus took shape in a multiplicity of aspects: first, it is true, only in the intensification of excavation campaigns (and in the assiduous, almost feverish, visitation of the memories of the past), but later also in the exceptional flourishing of the market or of antiquarian collecting. It also resulted in passionate mythmaking or, on the contrary, in rational study and cataloguing of materials, as well as in the establishment of new bodies for the protection of the artistic heritage, just as occurred in Naples under Charles of Bourbon, where for the first time, in an attempt not to disperse the material found, several important legislative measures were taken to regulate excavations, protect works of art and restrict their trade. It is one of the great innovations that produced the sensational rediscovery of the two cities engulfed in the fall (and not aroused, according to a recent hypothesis) of 79 by lava and fire. In addition, the letters, reports, and invaluable memoirs of the many foreign travelers, (Saint-Non, Lenormant, Stendhal) and especially the collections of engravings and drawings drawn from the finds, have been fundamental tools for knowledge and study as well as the transposition of the ancient.

Ultimately, in the words of Joan Didion, “the past was perhaps different from the way we like to perceive it.” The past, especially starting with the archaeological past found in Pompeii and Herculaneum, is always imagined. While it is perceived as a reassuring and positive myth to be addressed, it has also been understood as an immense, paralyzing and sublime ruin of something that more often than not leaves allartist minimal and limiting spaces. Prominent is the case of Füssli, who traces in his pivotal work, The Artist’s Despair before Ruins, the dismay felt before the magnificence of ancient remains. Canova, too, was not to be outdone: at the beginnings of his career he was also the victim of criticism. There is the diary to confirm this: when he arrived in Rome, he was preceded by a reputation as a rebel; it was held against him that he hated the ancient and wanted to invent. Simpone therefore an idea of ancient considered a language to be emulated, not reinterpreted. In this same vein, in the objects d’uso so widely surfaced by excavations, critics and intellectuals of the time took different attitudes. Either they did not understand the importance of the rediscovery, when they did not deny the possibility of visiting and copying the finds at the excavations, or, but only later, they grasped, alongside the fact of their beauty, that rationality and functionality that might be able to interpret the spirit of the time and promote the social redevelopment, which the Enlightenment had set out to pursue. Finally, Herculaneum and Pompeii, epicenters of archaeological rediscoveries in the 18th century, were also assigned, but only exceptionally, a major historical role. The reemergence, the résurrection of the two cities undoubtedly marked a turning point. After their rediscovery there was a radical change in the gaze of artists, scholars, and collectors throughout Europe. However, neither Herculaneum nor Pompeii would be enough to remake the ancient. It was not a process that started immediately, in the aftermath of the excavations: it would happen only later, from the nineteenth century onward, when the first truly scientific investigations could be conducted, the first excavation campaigns supported with a more rigorous methodology. Until then the watchword was “collecting material (i.e., stones) for construction” (so Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli) for a future historical building.

“This state of affairs,” says Bianchi Bandinelli, “contributed to the emergence and persistence of the concept established by Winckelmann that the history of ancient art had had its culmination in the Golden Age, with Phidias, and then declined.” And this conception of art as parabolic, which included the error of “didentifying above all a particular period of Greek art with the Absolute of Art,” “took it away from its historical process and ended up substituting a myth for it,” a substitution that also ended up informing much of eighteenth-century art

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.